Tiles

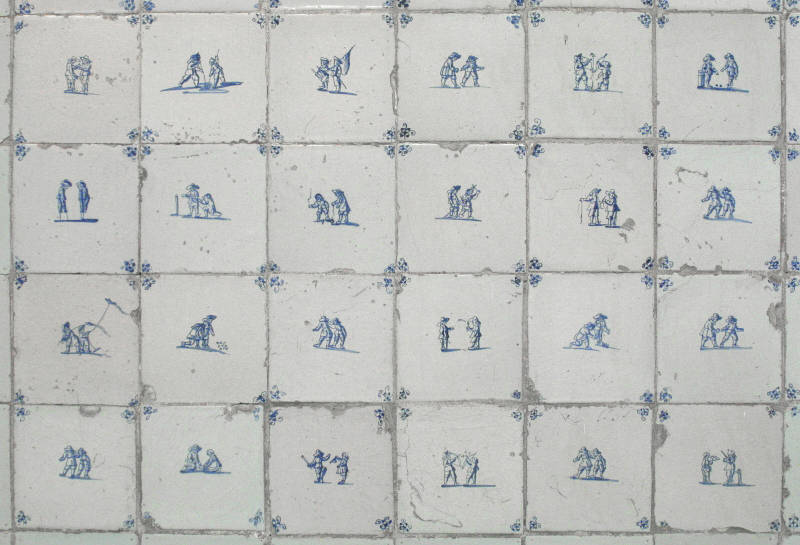

In addition to producing imitations of finely crafted Chinese Kraak tableware, the artisans of Delft became widely known for their vast output of humble tin-glazed Delft tiles. These square tiles, typically measuring around thirteen centimeters per side, featured hand-painted designs and were commonly used to decorate fireplaces, kitchens, and walls (fig. 1). Both decorative and functional, their glossy surfaces served to protect porous surfaces while enhancing the aesthetic of the space. These tiles were adorned with corner motifs, known as hoekmotieven which framed the central image. These designs, typically featuring simple elements like stars, flowers, or geometric shapes, are placed in each corner of a tile. When multiple tiles are installed together, the hoekmotieven align to form continuous patterns or frames around the central images of adjacent tiles, creating a cohesive and interconnected design across the tiled surface (fig. 2). This technique enhances the visual unity of the installation, allowing individual tiles to contribute to a larger, harmonious composition.

The forerunners to Delftware tiles were heavy floor tiles adorned with vibrant polychrome decoration, widely produced across Europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. These tiles drew inspiration from Italy's sophisticated maiolica, a tin-glazed earthenware characterized by its intricate, multicolored designs. Maiolica, often reserved for the wealthy elite, was used to embellish private residences and religious spaces, showcasing bespoke motifs such as heraldic emblems or symbolic imagery. This tradition spread to the Netherlands, where Dutch artisans refined and perfected the technique of tin-glazing during the 1660s, although the thinner glazed Delft tiles could not withstand the wear and tear of pavements.

The popularity of Delft base-board tiles transcended social classes. Middle-class households often purchased simply decorated tiles or factory seconds, while aristocratic families commissioned elaborate tiled rooms. In Vermeer’s paintings, these tiles perform the unglamorous yet essential role of protecting the lower parts of whitewashed walls from the daily assualt of of mops and brooms. Beyond walls, Delft tiles were used around chimneypieces, in corridors, on staircases, and even as lintels. Remarkably, some Dutch houses still retain original tiles from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These humble objects, which rarely bore factory markings of any kind, doubled as ship ballast during the long and dangerous voyages to the Orient, which could be sold for a profit at the destination.

While initially inspired by Chinese porcelain imported through the VOC, Delft tile designs began to incorporate uniquely Dutch imagery, such as farm workers, animal figures (dierfiguren) windmills, tulips, landscapes (landschapjes) children at play, and sailing ships, as well as biblical (bijbelse voorstellingen) and mythological themes. A notable example is a 1650 tile depicting a merman wearing a top hat.

The representation of children at play as a subject in northern art evolved distinctly from its southern Mediterranean counterpart, reflecting cultural, social, and religious differences between the regions during the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

1560

Oil on panel, 118 x 161 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

In northern European art, particularly in the Low Countries, the motifs of children engaged in play were often connected to the moralizing tendencies prevalent in Protestant contexts. These scenes were not merely celebrations of childhood but carried layered meanings, such as cautionary messages or allegories about the fleeting nature of life and the virtues of discipline. The works of Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525/1530–1569) are seminal in this tradition. His painting Children's Games (1560), for example, is an extensive panorama of children at play, where the activities not only showcase the diversity of childhood games but also serve as a commentary on human behavior and folly, reflecting a broader societal introspection characteristic of Northern Renaissance art.

By contrast, in southern Mediterranean art, particularly in Italy and Spain, representations of children were more often tied to religious themes or idealized visions of family life. The emphasis on Catholic religious narratives meant that depictions of children frequently appeared in contexts like the Holy Family or cherubic angels, symbolizing purity and divine innocence. Playful scenes, when present, tended to be less focused on everyday life and more idealized or decorative, aligning with the broader aesthetic and spiritual aims of the art produced in these regions.

This divergence reflects broader cultural patterns: northern art often grounded itself in depictions of daily life, with an interest in social commentary and moral reflection, while southern art leaned toward idealization and religious representation, shaped by the dominance of the Catholic Church and its emphasis on transcendence over earthly concerns. Thus, the northern tradition of children at play stands out as a distinctive lens for understanding societal values and artistic priorities in contrast to the Mediterranean approach.

Frans Hals Museum

Haarlem

Delft tile production progresed from individual tile motifs each confined within the boundaries of a single til, eto expansive, multi-tile compositions.

As the craft evolved, artisans began to create larger, interconnected designs that spanned multiple tiles, forming continuous scenes or patterns across expansive surfaces. This development was influenced by the Dutch Golden Age's artistic flourishing and the increasing demand for elaborate interior decorations. Technological advancements in tile production, such as improved tin-glazing techniques, allowed for greater uniformity and precision, facilitating the assembly of extensive, cohesive designs.

The transition from single-tile motifs to multi-tile compositions in Delftware reflects a broader trend in decorative arts, where the integration of individual elements into unified designs enhanced the aesthetic complexity and narrative potential of architectural spaces. This evolution underscores the adaptability and innovation of Delft artisans in response to cultural and artistic influences of their time.

Estimating the exact number of Delft tiles produced during the height of their popularity in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is challenging due to the lack of comprehensive production records. However, it is widely acknowledged that their production was extensive. Some estimates suggest that approximately 800 million Delft tiles were produced over a period of two hundred years.

Vermeer's Delft Tiles

Vermeer painted approximately twenty-four or twenty-five domestic interiors, five of which feature Delft baseboard tiles. Additionally, there are four other paintings where the interior is depicted in sufficient detail to determine whether tiles are present, yet they are notably absent in these works.

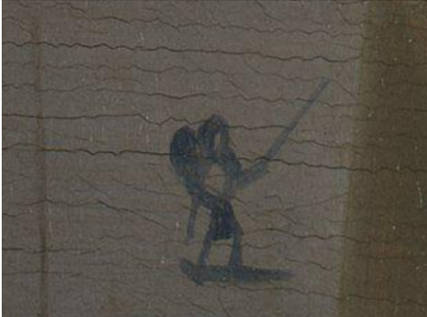

The presence of tiles in Vermeer’s paintings reflects their decorative role in seventeenth-century Dutch interiors and their function as a medium for conveying deeper narrative and symbolic meanings. In several works, art historians have conjectured that tiles play a narrative role that enhances the thematic depth of the scenes. For instance, in A Lady Standing at the Virginal, a tile featuring a fishing Cupid is said to symbolize love and courtship, consistent with the emblematic use of Cupid in seventeenth-century visual culture (fig. 3 & 4) . Art historian H. Rodney Nevitt Jr. pointed out that the Cupid tile near the woman’s skit, who seems to be holding up a fishing pole notwithstanding the abstract treatment of the passage, resembles a print in Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft's Emblemata amatoria, which plays on the comparison between fishing and courtship. Other elements, such as the large painting of Cupid in a black frame and the virginal, further reinforce this theme of love. Similarly, tiles depicting aquatic motifs, such as sailboats, evoke broader metaphoric themes, including emotional states or romantic pursuits. This contextual layering aligns with Vermeer’s practice of infusing his compositions with subtle yet profound elements that enrich their interpretative potential.H. Rodney Nevitt Jr., "Vermeer on the Question of Love," in The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer, ed. Wayne E. Franits (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 89–110.

Pieter Cornelisz. Hooft

1611

Engraving, dimensions unknown

Publisher: Willem Jansz. Blaeu

Place of Publication: Amsterdam

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 51.7 x 45.2 cm.

National Gallery, London

Tiles also serve as markers of cultural familiarity. Delftware, a hallmark of Dutch craftsmanship, was widely recognized and valued in Vermeer’s time. The patterns and motifs adorning these tiles carried implicit meanings that contemporary viewers would have understood. Their inclusion adds authenticity to Vermeer’s domestic scenes while grounding them in the material culture of his era.

Vermeer’s meticulous attention to spatial and textural details is evident in his integration of tiles into his compositions. Beyond their decorative appeal, tiles contribute to the realism and coherence of his interiors. In The Milkmaid, a notable tile displays a Cupid with a cocked bow, positioned between the milkmaid's voluminous skirt and the rustic foot warmer nearbyem which has been interpreted by Vermeer scholars such as Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Walter Liedtke. Liedtke, for instance, suggests that the this particular tile casts the milkmaid as a "discreet object of desire," subtly imbuing the scene with an undercurrent of romantic longing.Walter Liedtke, Vermeer: The Complete Works (London: Abrams, 2008), 76. On the other hand, Wheelock suggests that it is emblematic of themes of love and desire, integrating Vermeer’s broader interest in emblematic traditions. However, Wheelock also acknowledges the broader ambiguity of such elements in Dutch genre painting, noting that tiles like this were common in Dutch interiors and might not always carry a specific symbolic meaning in every context.Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Ben Broos, Johannes Vermeer (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 110. In all probablity, such motifs, familiar to the most exigent contemporary viewers, would have evoked associations with the complexities of love and desire.

While open to debate, such interpretations underscore Vermeer’s ability to use small details to generate layered meanings. Wheelock offers a borader, alternative view of the The Milkmaid as a whole, describing the milkmaid as a madonna of the cow-meadows who embodies purity and wholesomeness, an "ideal of human dignity" with a "physical or moral presence unequalled by any other figure in Dutch art."Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Ben Broos, Johannes Vermeer (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 64.

Skeptics, such as Taco Dibbits, argue that Cupids were common motifs on tiles found throughout Dutch households, and their inclusion in Vermeer’s work may be coincidental, without any intended symbolic meaning. This ambiguity invites varied interpretations, encouraging viewers to engage deeply with Vermeer’s artistry.

In any case, through his use of tiles, Vermeer bridges the everyday and the symbolic, transforming a common element of domestic decoration into a vehicle for thematic exploration.

Why Delftware Succeeded Despite Being an Imitation

Despite being an imitation of Chinese Kraak, Delftware achieved remarkable success in the seventeenth century due to its affordability, adaptability, and accessibility. While Kraak was highly prized for its translucence and exotic allure, its status as an imported luxury good rendered it expensive and limited in supply, especially during periods of political instability in China. In contrast, Delftware provided a more economical alternative, crafted locally using tin-glazed earthenware techniques. This made it accessible to a broader audience, including the burgeoning Dutch middle class, who desired the aesthetic appeal of blue-and-white ceramics without the prohibitive cost of imported porcelain.

Dutch artisans skillfully adapted the designs of Kraak porcelain, incorporating familiar motifs that resonated with European tastes, such as tulips, windmills, and biblical scenes. Practical innovations, like the creation of klapmutsen (wide-rimmed bowls tailored for European dining habits), further cemented Delftware's appeal. By blending the exotic charm of Chinese motifs with distinctly local elements, Delft potters created a product that felt both sophisticated and accessible.

Furthermore, Delftware's local production ensured a reliable and consistent supply, sidestepping the uncertainties of long-distance trade and the geopolitical disruptions that frequently hindered the importation of Chinese porcelain. While Delftware lacked the translucence and refinement of true porcelain, its vibrant blue-and-white designs and adaptability to consumer preferences met the growing demand for fashionable ceramics. This combination of affordability, cultural relevance, and availability allowed Delftware to thrive in both domestic and international markets, establishing it as a hallmark of Dutch artistry and ingenuity during the seventeenth century.

Fine Art Painters Involved in the Production of Delftware

De Haan, David, and Femke Diercks. "Leonaert Bramer and Delftware: Additions and Missing Links." Rijksmuseum Bulletin 71, no. 2 (2023): 127–134.

Delft painters involved in the production of Delftware played specific roles in the intricate division of labor within Delftware potteries, reflecting the collaborative nature of this craft. The process, overseen by the Guild of St. Luke, integrated both artistic and pre-industrial methods. Prominent artists such as BramerNotably, the ductile Bramer was among the few Dutch artists of his time to engage in fresco painting—a medium uncommon in the Netherlands due to its humid climate, which posed challenges for the durability of such works. Bramer executed frescoes in several significant locations, including the Civic Guard house and the stadholder's palaces in Honselersdijk and Rijswijk, as well as the Prinsenhof in Delft. Unfortunately, none of these frescoes have survived, likely due to the environmental conditions that made preservation difficult. contributed designs that were adapted for use in Delftware production.

To replicate the same decoration on large quantities of Dutch tiles, tilemakers used a technique called pouncing with the aid of stencils. These stencils included moedersponzen (mother stencils), which contained the original design, and werksponzen (work stencils), which were perforated to allow charcoal powder to outline the design on the pottery's surface. Poucing was done once the tile had received its first firing, or biscuit firing, and initial glazing. After this an outline drawn on paper was pricked with small holes and then the paper was laid on the tile and lightly hit with a porous bag filled with charcoal. This transferred the outline on to the tile. This outline was then painted over in a coloured pigment using a fine brush and fired once more. Painters would then refine the transferred designs, ensuring consistency while incorporating artistic flair. This technique allowed Delftware to feature a wide range of motifs, from biblical and mythological scenes to Asian-inspired Chinoiserie designs.Chinoiserie refers to the European interpretation and imitation of Chinese and East Asian artistic traditions, which became highly fashionable in the 17th and 18th centuries. Rooted in the fascination with imported Chinese goods, such as porcelain, silk, and lacquerware, Chinoiserie blended elements of Eastern aesthetics with Western design sensibilities. This style often featured fantastical depictions of pagodas, landscapes, floral motifs, and exotic figures, emphasizing a romanticized and often inaccurate vision of Asian culture.

The pouncing method, known as spolvero in Italian, has been a significant technique in European art for transferring designs across various surfaces. This process involves pricking small holes along the outlines of a drawing and then dusting a fine powder, such as charcoal or chalk, through these perforations to create a dotted outline on the target surface.

During the Renaissance, artists like Michelangelo and Raphael utilized pouncing to transfer preparatory cartoons onto surfaces designated for frescoes or canvases, ensuring accuracy and consistency in large-scale compositions. This technique was also adopted in Northern European art studios, facilitating the replication of intricate designs across various media, including paintings, tapestries, and prints.

Pouncing was particularly useful in fresco painting, where artists transferred detailed cartoons onto wet plaster surfaces to guide the painting process. In tapestry production, full-scale cartoons were pounced onto warp threads to direct weavers in executing elaborate patterns and scenes. Artisans also applied pouncing to transfer designs onto ceramics, ensuring uniformity in decorative motifs across multiple pieces. In this method, the desired drawing is created by pricking small holes along the outlines of a design on materials like paper, parchment, or metal. The stencil is then placed on the ceramic surface, and a fine powder—such as charcoal or graphite—is dusted over it.

With advancements in transfer techniques, such as tracing and the use of carbon paper, the reliance on pouncing diminished. However, its historical significance remains evident in the precision and uniformity of design in numerous Renaissance artworks.

Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674) , who was one of the most esteemed Delft artists, was, in fact, actively involved in creating designs for a variety of artistic mediums. In addition to his work as a painter, he contributed to wall and ceiling decorations and provided designs for the Delft tapestry industry. His versatility across disciplines is notable, especially considering that he is the only seventeenth-century Delft painter known to have produced such an extensive body of drawings—over 1,100 of his works have survived. These drawings served as a critical link between the conceptualization and execution of projects, facilitating the transfer of ideas across different artistic crafts.

Notable among fine art painters who worked independently within the Delftware sector were also Isaac Junius (1616–after 1672s, Gijsbrecht Verhaest, and Frederick van Frytom. The collaborative and modular nature of Delftware production underscores its distinction as both a craft and an artistic endeavor, bridging the gap between individual creativity and industrial efficiency.

Dutch Paintings with Kraak: Still Lifes and Domestic Interiors

Attributed to Jan Jansz. van de Velde III

c. 1650–1660

Oil on canvas, 44.7 x 38.8 cm.

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

White the prosaic Delft base-board tiles appear in countless domestic interior scenes, Delftware and Kraak frequently appear in seventeenth-century Dutch still-life paintings as a central element, reflecting its prominence in domestic life and its status as a symbol of wealth and cultural engagement (fig. 5). Go back a decade or two and Chinese dishes rarely make appearances in Dutch paintings, but go forward a decade or two and they are everywhere.Timothy Brook, Vermeer's Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2008), 55.

Artists such as Willem Kalf (1619–1693) (fig. 6) and Pieter de Ring (1615/1620–1660) (fig. 7), famous for his opulent, flashy still lifes or banquet pieces with fruit, a lobster, a goblet, shrimps, and oysters, often included porcelain in their compositions, showcasing the intricate designs and craftsmanship of these ceramics. The shiny surfaces and vivd blue decorative patterns not only complemented the textures and rich colors of natural fruits and vegetables, creating striking contrasts that heightened the overall realism and aesthetic appeal of the scenes, but likewise provided a means to showcase the painter's skills in representing textures and the effects of light. Kalf's still lifes often feature porcelain alongside luxurious items like silverware and exotic fruits, emphasizing themes of abundance and the transience of earthly pleasures. These depictions not only provide insight into the material culture of the period but also serve as a testament to the aesthetic appreciation of Delftware in Dutch society.

Willem Kalf

1669

Oil on canvas, 78 x 66 cm.

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Indianapolis

Pieter de Ring

Date unknown

Oil on canvas, 128 x 139.5 cm

The Wallace Collection, London

Vermeer was one of many Dutch interior painters who included local Delftware and imported Kraak in their compositions. A piece of Kraak appears tilted on the carpet-covered foreground table of Vermeer's Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (fig. 8 & 9), which is directly comparable piece in the Dresden Porzellansammlung, originating from Jingdezhen. Scholars have suggested that it belongs to the "'transitional Kraak hybrid style" and dates to the late Ming Dynasty.Stephan Koja, Uta Neidhardt, and Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Johannes Vermeer: On Reflection, (Dresden: Sandstein Verlag, 2021), 159. The porcelain features richly faceted blue tones and decorated wells with panelled margins characterized by stylized tulips, carnations, and other floral designs.

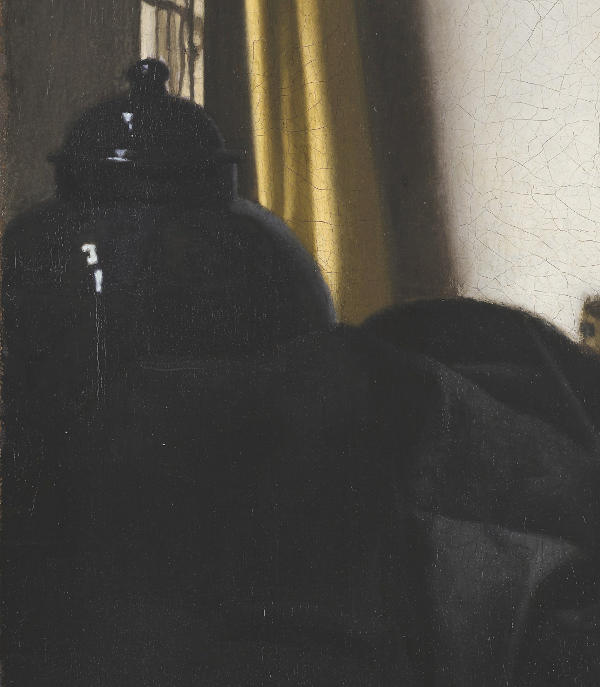

In the artist's Woman with a Pearl Necklace, (fig. 10 & 11), a large porcelain jar looms to the extreme left of the dimly lit foreground. Traditionally identified as Chinese—possibly a ginger jar—this vessel has been reevaluated by scholars Christina An and Menno Fitski. In their 2023 article, "Vermeer’s Jar," published in The Rijksmuseum Bulletin,Stephan Koja and Uta Neidhardt, Johannes Vermeer: On Reflection, (Dresden: Sandstein Verlag, 2021), 159. they propose a differnt origin.

According to the two scholars, the jar depicted by Vermeer exemplifies the early stages of Japanese porcelain export to Europe, which arose in the mid-seventeenth century due to disruptions in Chinese production following the fall of the Ming dynasty. These disruptions prompted the VOC to source porcelain from Japan, where potters adapted Chinese designs to meet European tastes. The jar in Vermeer's painting, with its cartouches and blended decorative motifs, reflects this adaptation. Vermeer's inclusion of this Japanese piece, set within a distinctly Dutch domestic interior, serves as a reminder of how cultural exchange and material wealth were visually represented in the art of the period.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1657–1659

Oil on canvas, 83 x 64.5 cm.

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 55 x 45 cm.

Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Johannes Vermeer

Johannes Vermeer

Postcript

"With the production of Delftware, the earthenware industry grew enormously in the second half of the seventeenth century. In 1640, there were eleven factories with an average of fifteen painters and servants. In 1670, the number of factories grew to twenty-eight and with approximately sixty employees per factory. Although the potters' wealth and social influence was less than that of the former brewers, the pottery industry became the most important employer in the city of Delft. In the course of the eighteenth century, however, mutual competition became increasingly fierce and the sales market was also threatened. This resulted in the decrease of the number of factories; in 1750, twenty factories were still active and a mere eleven at the end of the century.""The City of Delft in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries," Aronson Delftware, accessed November 28, 2024, https://www.aronson.com/city-of-delft-seventeenth-eighteenth-centuries/. Only a few factories in the town have continuously produced in the tradition since the sixteenth century. In Britain, Delftware went out of style over the course of the nineteenth century as the industrial potteries in Staffordshire developed new techniques for making blue and white ceramics that were lighter and more durable than tin glazing.

B

- Banding Wheel: A manually operated, rotating platform used by potters to decorate or shape ceramic pieces uniformly. It allows for precise control when applying decorations or trimming.

- Bisque: Unglazed ceramic ware that has undergone bisque firing. It is porous and ready to accept glaze applications.

- Biscuit firing: The initial firing of unglazed earthenware, which produces biscuit wares.

- Body: Fired clay with no glaze or enameling.

C

- Casting Slip: A liquid mixture of clay and water with added deflocculants used in slip casting to form ceramic objects in plaster molds.

- Chamotte clay: Pre-fired clay that is added to raw clay used to make pots to produce a stronger body.

- Charger: Chargers have a diameter of 26 centimeters or more. Smaller versions are generally referred to as plates.

- China Clay: Another term for kaolin, the primary clay used in porcelain production due to its purity and whiteness.

- Chinoiserie: The use of motifs derived from Chinese art to give objects made in Western Europe an "exotic" appearance. The Delft pottery industry was instrumental in establishing this fashion.

- Craquelure (crackle): Hairline cracks in the glaze caused during glaze firing as the glaze and body shrink at different rates.

- Creamware: A hard type of earthenware with a cream-colored body covered with a transparent lead glaze.

- Crystalline glaze: Glaze with small crystals on the surface formed as a result of gradual cooling of metal oxides in the glaze.

D

- Delftware: English term for tin-glazed earthenware, referencing the Dutch town of Delft. Capitalized, it refers specifically to Delft earthenware; lowercase refers to tin-glazed earthenware made anywhere.

E

- Earthenware: A type of ceramic with a porous body, created at firing temperatures of approximately 800–1150°C. Must be glazed to be watertight.

- Eggshell porcelain: Porcelain with extremely thin walls, often translucent, resembling eggshells.

- Enamel: Vitreous pigment (either opaque or transparent) that is coloured with metal oxides applied to the surface of ceramics, typically as overglaze decoration requiring a lower-temperature firing.

F

- Factory mark: A mark referring to the pottery, usually referencing the name of the pottery or its proprietor or manager.

- Faience: Tin-glazed earthenware, often with a thin body and smooth front surface.

- Familles: Enamelled Chinese porcelain is traditionally divided into different colour families (‘famille’ being French for family): vert (green), rose (pink), noir (black) and jaune (yellow). These categories were defined in Europe in the 19th century.

- Feldspar: A group of minerals used in ceramic bodies and glazes as a flux to lower the melting point.

- Firing;The entire process of heating and cooling off pottery in the kiln. There were usually two firings: the biscuit firing and the glaze or glost firing.

- Flatware: Collective term for flat items like plates and platters, to distinguish them from hollow wares.

- Flux: A material that promotes melting or fusion in glazes and clay bodies by lowering the melting point of silica.

- Foot Ring: The circular base of a ceramic piece, often left unglazed to prevent it from fusing to kiln shelves during firing.

G

- Glaze: Vitreous layer on the surface of ceramics.

- Glaze or Glost Firing: The second firing, designed to fuse the glaze to the surface at a temperature of approx. 1000° C. To prevent objects from fusing together in the kiln, they are separated using spurs or pegs and saggars.

- Grand feu technique: The process of firing objects at approximately 1000°C, often during the second (glaze or glost) firing.

I

- Imari porcelain: Type of Japanese porcelain whose decorative style, named after the port of Imari, was imitated in (a.o. China and also) Delft. The blue, red and gold porcelain first appeared on the Dutch market around 1680.

K

- Kakiemon porcelain: Type of Japanese porcelain whose decorative style was imitated in Delft, among other places. The multicoloured porcelain with refined decoration (named after a family of potters) first appeared on the Dutch market around 1680.

- Kangxi porcelain: Type of Chinese porcelain developed during the Kangxi period in the Qing dynasty (1662-1722).

- Kaolin or China clay: A type of clay essential for porcelain production.

- Kendi: Jug with a round body. The neck or spout sits on the rounded shoulder. Some are in the shape of animals (including elephants, ducks and fish). Kendi were used throughout Southeast Asia and the Middle East. A porcelain version of this form was introduced to the Netherlands in the early 17th century.

- Kraak ware or Kraak porcelain (see Wanli porcelain): A type of Chinese porcelain made in the time of Emperor Wanli (1573-1619) and his successors, right through to the fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644. The distinctive blue decoration is divided into panels and applied on a white ground.

- Kwaarten: Traditional Dutch term for the application of a top layer of transparent lead glaze (kwaart) to produce a brilliantly shiny surface. Also known as coperta.

L

- Lead glaze: A transparent glaze whose main component is lead oxide.

- Leather-hard: The stage of clay dryness where it is firm yet still retains moisture, allowing for carving, joining, and trimming without distortion.

- Lustre glaze: Glaze with a metallic shine, obtained by the addition of metal oxides.

M

- Majolica: Tin-glazed earthenware with a layer of tin glaze on the front and transparent lead glaze on the back.

- Maker’s mark: A mark used by a craftsman to show the workshop where objects were made.

- Marl: Adding earth from Tournai (known in Dutch as Doornikse aarde) to clay produced a pale yellow body.

- Molding: Forming ceramic pieces by pressing clay into a rigid mold, allowing for the production of uniform shapes. Muffle kiln: Small kiln used to fire smaller batches of pots. Some gilders had kilns of this type on the premises, presumably to fire gilded pieces using the petit feu technique. Hence the Dutch term ‘goudschilderoven’ (= gilder’s kiln).

O

- On-glaze: Decorative enamels applied over the glaze layer and fired at low temperatures to fuse the decoration without affecting the underlying glaze.

- Oxidation firing: Allowing oxygen in during the glaze firing so that clay containing iron oxide, for example, turns red.

P

- Pâte-sur-pâte: Decoration produced on porcelain using semi-liquid white porcelain slip, sometimes tinted with metal oxides.

- Petit feu technique; The process of firing objects at a temperature of approx. 600° C. This was usually done in small muffle kilns, known in Dutch as goudschilderovens (= gilders’ kilns), used for gilded objects and delicate colours that would be incinerated at higher temperatures.

- Plate: Plates have a diameter of up to 26 centimeters. Larger plates can also be referred to as platters.

- Plateel:Contenporary term for lead- and tin-glazed earthenware (majolica and faience). Also used to reference typical wares produced in the Netherlands in the early twentieth century.

- Plateelbakker: Dutch term meaning a producer of lead- and tin-glazed earthenware (majolica and faience).

- Plateelbakkerij: Dutch term for a pottery producing lead- and tin-glazed earthenware (majolica and faience).

- Plateelschilder: Dutch term for a painter specially trained to decorate earthenware.

- Polychrome: Decoration in more than one colour.

- Porcelain: Type of ceramic with a hard, non-porous body created by firing at a temperature of 1300-1500 ºC.

- Porceleyn (Porceleyne, porcellyne etc.): The old name used in Delft for tin-glazed earthenware that was meant to imitate porcelain.

- Pounce: Paper on which the outlines of a decorative design have been pricked out. The design is transferred to the object through the holes using powdered charcoal.

- Porcelain: A type of ceramic with a hard, non-porous body, fired at temperatures of 1300–1500°C.

R

- Reduction firing: A technique whereby the amount of oxygen entering the kiln during glaze firing (at a relatively high temperature) is reduced in order to produce colour variations and textured effects in the glaze.

- Running glaze: Glaze with a low melting point that runs when fired. Running glazes are applied on top of a glaze with a higher melting point.

S

- Saggar: A cylindrical earthenware container in which earthenware objects would be stacked for firing. To prevent the objects from fusing to the surface, each one would rest on triangular pegs inserted through the wall of the saggar. To protect the pots from kiln fumes, the saggar was closed during firing by placing tiles on top and underneath.

- Sgrafitto: Technique whereby decoration is incised into the surface of a ceramic object that is covered with a layer of slip (engobe).

- Shrinkage: The reduction in size of a clay body during drying and firing due to loss of water and densification of particles.

- Sinter engobe: A blend of engobe and a vitreous substance that produces a glaze-like shine on a ceramic object.

- Slip: Liquid clay used as an adhesive to stick together the different parts of an object during the production process.

- Slip Casting: Forming ceramic objects by pouring slip into a plaster mold, which absorbs water and forms a solid layer against the mold walls.

- Spur: Ceramic support used to separate pieces of majolica in the kiln during glaze firing and stop the pieces fusing together.

- Spur mark: Scar on the front of a piece of majolica caused by the spur used to support it in the kiln.

- Stoneware: Hard, non-porous ceramic fired at approximately 1200–1300°C.

T

- Thrower: A craftsman who makes objects on a potter’s wheel.

- Throwing: The process of shaping clay on a potter's wheel by hand while it spins, allowing for symmetrical forms. Tin glaze bath: Tub containing tin glaze into which the wares (biscuit) are dipped after the first firing, creating a white surface to which the painter can then apply the decoration.

- Transfer printing: Technique whereby a design printed on prepared paper is transferred to the surface of a ceramic object.

- Transitional porcelain: Blue-and-white Chinese porcelain produced in the period of transition between the Ming and Qing dynasties (during the reign of Emperor Shunzhi between 1644 and 1661). Its decoration is characterised by continuous narrative scenes.

- Translucency: The property of allowing light to pass diffusely through a material; in porcelain, it is a valued aesthetic quality.

- Throwing: The process of shaping clay on a potter's wheel by hand while it spins, allowing for symmetrical forms.

W

- Wanli porcelain: A type of Chinese porcelain from the time of Emperor Wanli (1573–1619), characterized by distinctive blue decoration.

- Wheel: A potter's wheel, a device that spins clay to facilitate the shaping of symmetrical ceramic forms.

X

- XRF: Research technology based on x-ray fluorescence used to measure the composition of materials, increasingly in studies of Delftware.

Bibliography

- Bang, Byung Sun. "Influence of Chinese Export Porcelain on Delftware during the Dutch Republic Era." Art History Journal 48 (June 15, 2017): 311–35.

- Carswell, John. Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain and Its Impact on the Western World. Exhibition Catalogue. Chicago: David and Alfred Smart Gallery, 1985.

- Caiger-Smith, Alan. Tin-Glaze Pottery in Europe and the Islamic World: The Tradition of 1000 Years in Maiolica, Faience and Delftware. London: Faber and Faber, 1973.

- Crowe, Yolande. Persia and China: Safavid Blue and White Ceramics in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1501–1738. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 2002.

- Hochstrasser, Julie. Still Life and Trade in the Dutch Golden Age. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Howard, David, and John Ayers. China for the West: Chinese Porcelain and Other Decorative Arts for Export, Illustrated from the Mottahedeh Collection. London and New York: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978.

- Jörg, Christiaan J.A. Porcelain from the Vung Tau Wreck: The Hallstrom Excavation. Singapore: Sun Tree Publishing, 2001.

- Kerr, Rosemary. "Early Export Ceramics." In Chinese Export Art and Design, edited by Craig Clunas. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1987.

- Kroes, Jochem. Chinese Armorial Porcelain for the Dutch Market: Chinese Porcelain with Coats of Arms of Dutch Families. Den Haag: Centraal Bureau voor Generalogie and Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, 2007.

- Pluis, Jan. The Dutch Tile: Designs and Names 1570–1930. Nederlands Tegelmuseum – Friends of the Museum of Otterlo Tiles. Leiden: Primavera Pers, 1997.

- Rinaldi, Maura. Kraak Porcelain: A Moment in the History of Trade. London: Bamboo Publishing, 1989.

- Savage, George. Pottery Through the Ages. London: Penguin, 1959.

- Vainker, S.J. Chinese Pottery and Porcelain. London: British Museum Press, 1991.

- Wu, Ruoming. The Origins of Kraak Porcelain in the Late Ming Dynasty. Weinstadt: Verlag Bernhard Albert Greiner, 2014.

- Wuestman, Gerdien. "Wouwerman on Delftware." Rijksmuseum Bulletin57, no. 3 (September15, 2009): 236–43.