A Maid Asleep

(Slapend meisje)c. 1656–1657

Oil on canvas, 87.6 x 76.5 cm. (34 1/2 x 30 1/8 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

acc. no. 14.40.611

The textual material contained in the Essential Vermeer Interactive Catalogue would fill a hefty-sized book, and is enhanced by more than 1,000 corollary images. In order to use the catalogue most advantageously:

1. Scroll your mouse over the painting to a point of particular interest. Relative information and images will slide into the box located to the right of the painting. To fix and scroll the slide-in information, single click on area of interest. To release the slide-in information, single-click the "dismiss" buttton and continue exploring.

2. To access Special Topics and Fact Sheet information and accessory images, single-click any list item. To release slide-in information, click on any list item and continue exploring.

The pretty young maid

The girl's face seems to resemble that of a young woman repeated in later paintings which some art experts believe to have been Catharina Bolnes, Vermeer's wife. According to Dutch costume expert Marieke de Winkel, who has examined the costumes of Vermeer's works, the maid wears a dark-red silk jacket and a pointed black cap called a hul and a pair of pearl earrings, all refined accouterments of the elevated social class. Over her dark-red dress she wears a shawl. This shawl is likely a kamdoek, typically worn to protect clothing while combing hair and often kept on throughout the day of the kind worn to protect clothing when the hair was combed and also often kept on during the day. As she hasn't completely closed it, a portion of her bosom is visible.

The hul was a type of tight-fitting, black, pointed bonnet or cap worn by women in the 17th century Netherlands. It often had a pronounced point or peak at the front. It was typically made of black silk or another fine material and was designed to fit closely to the head, resembling a skullcap in shape, worn alone or underneath other head coverings for added modesty or warmth. The hul was a distinctive feature of Dutch female attire during this period. The cap could be

But the "most remarkable" element of the young girl's smart getup, claims De Winkel, "is a black patch on the girl's left temple called mouche (beauty spot), considered to be the height of fashion," attached to the girl's right-hand temple. A mouche (plural: "mouches") in 17th-century fashion, particularly popular among the European elite, was a small patch or beauty mark, often made of silk, taffeta or velvet. These patches were could be cut into various shapes such as stars, crescents or hearts and were adhered to the face or sometimes the décolletage. While they originated as a way to cover up blemishes, scars or smallpox marks, mouches quickly evolved into a fashionable statement in their own right. Mouches were also worn to prevent toothaches and headaches and to make the skin appear whiter. To enhance this effect, white powder (blanketsel) was usually applied to the face, in a culture in which pure white skin was highly prized, topped off with rouge for the cheeks.

Even though there is much written evidence of these patches, they appear only rarely in paintings of the time. It is said that a sort of "secret language" even developed through their use: A patch near the mouth meant you were flirtatious; one next to the right cheek signaled you were married; one on the left cheek announced you were engaged; one at the corner of the eye meant you were somebody's mistress.

The influence of Gabriel Metsu

The Account Keeper (detail)

Nicolaes Maes

1656

Oil on canvas, 66 × 53.7 cm.

Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis

A Maid Asleep is Vermeer's initial exploration of the domestic interior theme popularized by Gabriel Metsu, Pieter de Hooch and Nicolas Maes. The composition includes several props and pictorial elements that he would use repeatedly throughout his brief 20-year career. While we can't discern the specifics, it's reasonable to suggest that this portion depicts a section of a wall map, a common and affordable decorative choice for empty walls. More distinguishable is the map's wooden hanging rod (referred to as rollen), frequently seen in Dutch genre interior paintings. Maps were typically glued to cloth to enhance their durability and make them rollable for storage. The weight of the lower hanging rod kept the map flat, and the unique balls kept it spaced from the wall, preventing contact with the ever-humid Dutch walls. In more modest homes, maps were simply fastened with tacks.

While contemporary scholars have delved deep into the potential symbolic meaning of. the items in Vermeer's composition, the symbolic significance, if any, has not been explained.

A colorful Turkish carpet

Because so few 17th-century carpets remain, European paintings have become a primary source for scholars studying early carpets. As a result, many groups of Islamic carpets from the Middle East now bear the names of European painters who featured them in their works. Esteemed European painters like Giotto, Ghirlandaio, Holbein, Van Eyck, Lotto and Vermeer have all depicted carpets from Turkey or Iran. Their paintings attest to the significant value the Oriental carpet acquired as an emblem of international refinement. Like all prized imports, there were attempts to replicate these carpets or modify them to align with European designs.

The carpet in A Maid Asleep has been recognized by Onno Ydema as a 17th-century Anatolian carpet from Turkey. Nine of Vermeer's works feature carpets, mostly of varying designs but always likely painted from an actual model. Remarkably, in the Northern Netherlands, only three carpets known to have been owned by the Dutch in the 17th century remain. The carpet in this particular painting is likely a Lotto design in a Kilim style. By the 18th century, the allure of oriental carpets had faded, perhaps due to the decreasing quality and quantity resulting from the decline of the dominant dynasties in the East.

For a typical 17th-century high interior Dutch painter, an imported carpet would have been an expensive but almost indispensable prop. While they could have been lent by accommodating clients, which explains why the same carpet tends to appear multiple times in the works of a single painter. It's known that carpets were sometimes passed down to the painter's son.

Due to the swift growth of the Netherlands' foreign trade, oriental carpets gained immense popularity during the 16th and especially the 17th centuries. They were primarily used as decorative pieces, draped over tables or chests with the knotted surface facing up. To prevent wear and tear, the Dutch typically displayed them on tables. This custom of presenting carpets on tables in affluent homes persisted until the close of the century, after which Oriental carpets diminished in prestige.

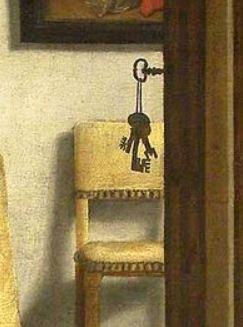

A "Spanish" chair

In the time of Vermeer, this kind of free-standing chair was known as a Spanish chair. Spanish chairs with two hand-carved in-head finials make frequent appearances in Dutch interior paintings and in Vermeer's oeuvre as well. The Spanish chair was distinct in design. It typically boasted a robust and solid framework, reflecting, perhaps, a blend of Moorish influences from Spain and the practicality of Northern European craftsmanship. The wood, often oak, was chosen for its durability and rich grain, which added to the chair's aesthetic appeal. The seating and backrest, crafted from thick leather, were fastened to the wooden frame with large, decorative nails. This combination of wood and leather not only provided comfort but also ensured the chair's longevity.

Manufacturing a Spanish chair required meticulous craftsmanship. The wood was carved and joined with precision, ensuring that every edge and joint was seamless. The leather, often tanned to a deep brown or reddish hue, was stretched taut over the frame. The decorative nails not only held the leather in place but also added an element of artistry, often arranged in patterns or designs that elevated the chair's overall appearance.

This chair, however, was not a part of Vermeer's original composition. It covers a standing dog near the doorway who looked towards the far end of the see-through room where a hatted cavalier once stood. Although it is very hard to make out, the thinly painted object propped up against the back of the chair is a cushion with a decorative gold braid. No explanation has been given to either object but it is possible that their function was to close the composition.

Another type of chair

The social history of the chair is as interesting as its art and craft. The chair is not merely a physical support and an aesthetic object; it is also an indicator of social rank. In this painting, Vermeer employed two different types of chairs in the painting which he never did again. The foreground chair was a later addition to the original concept of the composition. Its decorative lion-head finials became a standard feature of his interiors.

The chair on which the young woman is seated appears again in the late Love Letter, this time, the seat's decorative fringe can be clearly observed. Curiously,, laboratory analyses has suggested that Vermeer might have tried to use actual gold leaf to emulate the sheen of the brass knobs on the background chair, accentuated with a hint of lead-tin yellow. However, it's far more likely that the particles of gold leaf, also microscopically found in the iconic Girl with a Pearl Earring, were nothing more than an accidental contamination. Gold leaf is incredibly light and thin. It's so delicate that even a gentle touch can easily tear or wrinkle it, and a mere breath of air can scatter it as if it were as light as dust.

A hidden Cupid

Amor Holding a Glass Orb

Cesar van Everdingen

c. 1660

Oil on canvas, 89 x 102 cm.

Private collection

Although it often goes unnoticed by many who have seen the painting only in reproductions, above the head of the sleepy—for Walter Liedtke," tipsy"— maid is the corner of a dimly lit, ebony-framed picture-within-a-picture, which is likely based on an extant painting of a standing Cupid (or Amor) listed in the 1676 probate inventory of the artist's estate. If one has the luck to visit the Metropolitan Museum on a sunny day or has access to a state-of-the-art digital image of the painting, it's possible to discern the chubby leg of the Cupid and, in the lower corner, a theatrical mask. The same Cupid appears in three other compositions by Vermeer: The Dresden Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, painted shortly after the present canvas, the Girl Interrupted in Her Music, where the Cupid can barely be made out, and in the later A Lady Standing at a Virginal. The mask appears prominently in the Dresden piece, but curiously, it's absent in the London Lady Standing. The mask might suggest that love is unmasked in the latter context.

Whatever its significance, it was one of the artist's favorite props, and he must have been particularly fond of it, though the reason remains elusive. It may have been simply intended as a nod to the painter's supportive mother-in-law, to whom the Cupid probably belonged. From the professional style of the picture-within-a-picture as it appears in the Lady Standing at a Virginal in the London National Gallery, the painting likely came from the skilled hand of the successful classical painter Cesar van Everdingen or his studio.

Regardless of who might have painted it or how Vermeer may have come by it, the Cupid undeniably draws inspiration from emblems published in 1608 in Otto van Veen’s Amorum emblemata. One emblem portrays a very similar Cupid trampling a mask, a motif not evident in the London painting but observed in the recently uncovered painting within the painting in Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. The mask acts as a universally understood symbol for deceit, which true loves casts away. Perhaps this kind of enigma was precisely what a 17th-century audience, familiar with emblematic images from immensely popular emblem books, would have appreciated.

In the present work, the Cupid's presence may hint at the young maid's temporary state, be it drunkenness, melancholy or simple laziness. Its symbolic function might be either explanatory or cautionary.

An imported ceramic bowl

The ceramic bowl that holds various pieces of fruit was commonly referred to as a klapmut, a large soup bowl produced in Jingdezhen, China.

Chinese export porcelain, being valuable and highly sought-after items, frequently featured in 17th-century Dutch artworks. The provided illustration showcases a painting by Jan Jansz. Treck which includes two Kraak-style bowls, likely from the late Ming period, with the one in the foreground being a klapmut.

The klapmut is an interesting artifact of cultural exchange and adaptation. It was originally was made in Jingdezhen, China, especially for export to Europe during the late Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and into the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). Jingdezhen is often referred to as the "Porcelain Capital" due to its crucial role in producing fine porcelain for over a millennium.

What distinguishes a klapmut from other porcelain bowls is its unique shape: it has a broad and flared rim which then dips inward before curving out to form the bowl. This design was functional for the European manner of eating soupy dishes, allowing them to rest spoons conveniently on the bowl's rim. The Chinese drank their broth soups directly from a bowl with steep vertical sides and had no use for the European version.

Still Life with a Pewter Flagon and Two Ming Bowls (detail)

Jan Jansz. Treck

1651

Oil on canvas, 76.5 x 63.8 cm.

National Gallery, London

he very existence of the klapmut exemplifies how global trade led to cultural adaptations. As European demand for Chinese porcelain grew in the 17th century, Chinese potters and merchants began to tailor their designs to meet the specific needs and tastes of the European market.

The term "klapmut" is Dutch, derived from two words: "klap," which means "fold," and "muts," which means "cap" or "hat." The name is thought to refer to a type of foldable hat worn in Europe during that period, which the bowl's shape somewhat resembles. As European porcelain manufacturing techniques advanced, particularly in places like Meissen in Germany and Limoges in France, the import of Chinese porcelain, including klapmuts, began to decline. The design of European-made porcelain bowls also evolved, incorporating and adapting various features from imported models. Today, original klapmuts from the Ming and Qing periods are highly prized by collectors and can be found in museums around the world.

The illustration shows a painting by Jan Jansz. Treck that includes two Kraak-style bowls, probably late Ming, the one in the foreground a klapmut.

Opening up space: a see-through doorway

Couple with Parrot

Pieter de Hooch

1668

Oil on canvas, 73 x 62 cm.

Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne

Throughout his career, Vermeer devised various methods to enhance the atmosphere of his private spaces. The view into another room, known as doorkijkje, is prevalent in many Dutch interiors, including the Idle Servant by Nicholaes Maes, which likely influenced the present composition. The Dordrecht painter favoured rectilinear designs, a warm palette (rich in reds and browns) and soft shadows which, in his cosy interiors, surround the figure at a slight distance, allowing them light and intimacy. Vermeer seems to have been receptive to the design qualities of Maes, but uniterested by his Rembrandtesque palette.

In the context of Dutch Golden Age painting, the term refers to a compositional device where the viewer is presented with a view into an adjoining room or space through a door or a window. This offers a deeper sense of spatial depth and creates a layered narrative within the painting, allowing the viewer to glimpse multiple scenes within a single frame. These "views throughs" often contain thematic or symbolic elements that complement the primary scene. For example, while the foreground might show a domestic scene of a woman reading or a couple engaging in conversation, the background—visible through a door—could reveal children playing or a serene garden, adding context or commentary to the main action.

In the background, it is possible to make out an oak octagonal table (gateleg), covered with a deep red tablecloth. This table, which could be folded in half and placed with its long middle side against the wall, also appears in Vermeer's Milkmaid. In the probate inventory of Vermeer's dwelling in 1676, such a table was listed in the interior kitchen. This kitchen formed the heart of the family’s everyday life, and relatives, friends, and neighbours would have found their way here as well.

Hung above the table is either an ebony-framed mirror, perhaps like the one in Vermeer's Woman Holding a Balance or Woman with a Pearl Necklace, or perhaps a painting. To the immediate right are the wooden fixtures of a window, which recall those in the Officer and Laughing Girl.

Vermeer seems to have drawn inspiration from De Hooch's Couple and Parrot for his Love Letter painted a few years later. Doorkijkje are prominetly portrayed in more that half of De Hoogh's output, not only for its artistic merit but for for its salablity as well.

Vermeer created at least one other doorkijkje, mentioned in an auction catalog of 21 Vermeer paintings (Amsterdam, 1696) as "a gentleman washing his hands in a perspectival room with figures, artful and rare..." The details of this enigmatic painting remain scant, but its importance is evident from its selling price of 95 guilders, fifteen guilders more than the detailed Music Lesson, now a celebrated piece of the Royal collection.

A glass of white wine

There are two glasses on the table: a tipped-over roemer in the foreground (which lost definition during past cleaning) and a small wine glass in front of the maid contianing white wine. The latter appears to have been added after a sprig of grape leaves was removed; an autoradiograph reveals the bacchic motif branching to the right of the Wanh bowl.

The fact that the maid drinks, or has drunken wine contributes to what may have been the main theme of the painting. Walter Liedtke wryly summarised what may have been once starkly apparent to the typical Dutchman but is no longer today. "The dozing and probably somewhat tipsy maid is certainly overdressed. This attire, however, isn't unexpected for a working woman who has recently entertained a man other than Christ. A 1681 Amsterdam regulation prohibited household servants from donning silk garments and jewelry, which are evident in this portrayal. The woman's exposed neckline and beauty patch near her left eye also deviate from typical domestic attire. Furthermore, her posture and the scattered items in her surroundings, including the ajar door, traditionally symbolize neglected responsibilities."

In the time of Vermeer, wine was seen as the drink of affluence. Symbolizing wealth and status, it was a luxury primarily enjoyed by the upper echelons of society. The Dutch, with their vast and masterful trade networks, imported wines from regions as diverse as France, Spain and Germany. They not only traded but also influenced tastes, fostering a particular fondness among the Dutch for sweet white wines.

On the other side of the spectrum was beer, the drink of the common man. Universally available and economically accessible, beer found its way into households across the social hierarchy. The Dutch took pride in their diverse range of beers, from potent brews for special occasions to lighter varieties for daily consumption. Local breweries dotted the landscape, making beer a household staple.

An ambiguous still life

Since this rather complicated still life is in a ruinous state, neither its eventual iconographic meaning nor the objects themselves are entirely comprehensible.

The still life, although somewhat less skillfully depicted, would be more forecfully elaborated upon in a work that soon followed the present one, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. The upper ceramic soup dish, a Wan-li bowl imported from China, holds various fruits, likely apples and plums. To the lower left, there's a white porcelain wine jug with a silver cap, which appears in other paintings by Vermeer. He must have appreciated its clean surface quality and evocative shape. It's believed to be from Italy, although Dutch replicas were prevalent. To the right of the expensive ceramic dish, a short white jug is tilted on its side, partly obscured by sheer fabric. Beneath the wine jug, the remains of a Roemer glass are evident, which may have deteriorated due to age or inexpert restorations. Just to the right of the Roemer lies a silver knife, oddly positioned next to what seems to be a spoon. Above these, there are a few nutshells and a nearly indiscernible glass filled halfway with white wine.

Complicating interpretations, an empty plate near the girl's fingertips and some sprigs of grapevines were both painted over by the artist. Other alterations, including a dog and a standing cavalier, pose questions about the young artist's initial intentions, suggesting that he grappled with the intricacies of the emerging interior genre, which would soon dominate his work. Regardless, such revisions would become a common practice for Vermeer.

special topics

- Vermeer's Beginnings

- Meaning and Money: A Patron for Vermeer

- First Efforts in a New Genre

- Vermeer's "love affair" with Cupid

- A Secret Key?

- Drunk, Depressed, or Asleep?

- The Missing Cavalier ans Dog

- Maid or Mistress?

- Difficulties with Iconography

- The Doorway in Dutch Painting

- A Mask of Deciet?

- Period Music

Critical assessment

In A Girl Asleep, the Soldier and Laughing Girl and the Dresden Letter Reader, Vermeer's matter is stated in a vocabulary not essentially different from that current among his contemporaries. In The Letter Reader the hands are modeled with almost painful attention to the known anatomical form; the same uneasy linear definition of these details appears in the Frick picture. Both reveal the painter with a manner antithetical to what he later developed.

Lawrence Gowing, Vermeer, 1952

The signature

Singed at left, above the figure's head: I.VMeer: (VM in monogram)

(Click here to access a complete study of Vermeer's signatures.)

Dates

c. 1657

Albert Blankert, Vermeer: 1632–1675, 1975

c. 1657

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer, London, 2000

c. 1656–1657

Walter Liedtke, New York, 2008

c. 1657

Wayne Franits, Vermeer, 2015

(Click here to access a complete study of the dates of Vermeer's paintings).

The painting in its frame

Provenance

- (?) Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven, Delft (d. 1674);

- (?) his widow, Maria de Knuijt, Delft (d. 1681);

- (?) their daughter, Magdalena van Ruijven, Delft (d. 1682);

- (?) her widower, Jacob Abrahamsz Dissius (d. 1695);

- Dissius sale, Amsterdam, 16 May, 1696, no. 8;

- probably sale, Amsterdam (V. Posthumus), 19 December, 1737, no. 47, sold to Carpi;

- [probably J.B.P. Lebrun, Paris, in 1811];

- Smeth van Alphen et al. sale, Paris (Lebrun), April 1811, no. 150, sold to Alexandre-Joseph Paillet, in 1811;

- John Waterloo Wilson, Paris (after 1873–1881;

- his sale, Paris, 13–16 March, 1881, no. 116, to Sedelmeyer, Paris, 1881, sold 1881 to Rodolphe Kann, Paris (d. 1905); his estate, 1905–1907;

- sold to Duveen, London, 1907–1908; sold 1908 to Benjamin Altman, New York (d. 1913);

- since 1913 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Benjamin Altman (acc. no. 14.40.611).

Exhibitions

- London 1898

Illustrated catalogue of 300 Paintings by Old Masters of Dutch, Flemish, French and English School Being Some of the Principal Pictures Which Have at Various Times Formed Part of Sedelmeyer Gallery

Sedelmeyer Gallery

104, no. 88 and ill., as "The Sleeping Servant" - London April 28–July 25, 1903

Works by Early and Modern Painters of the Dutch School

Art Gallery of the Corporation of London

no. 188, as "The Cook Asleep," lent by Monsieur x of Paris - New York September 25–October 9, 1909

The Hudson-Fulton Celebration

Metropolitan Museum of Art

no. 137, as "A Girl Sleeping" - New York November 7, 1952–September 7, 1953

Art Treasures of the Metropolitan

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

no. 117 - New York March 8–May 27, 2001

Vermeer and the Delft School

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

no. 67 - New York September 18, 2007–January 6, 2008

The Age of Rembrandt: Dutch Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art

no catalogue - New York September 9–November 29, 2009

Vermeer's Masterpiece "The Milkmaid"

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

no. 6 and ill.

(Click here to access a complete, sortable list of the exhibitions of Vermeer's paintings).

| Vermeer's life |

Maria Thins, in the first draft of her testament, leaves to Vermeer's daughters jewels (wrings bracelets and gilded chains) and the sum of three hundred guilders to Vermeer and Catharina. In the same testament Maria Thins wills to Vermeer's first child, Maria, 200 guilders. The child's name is an almost certain sign of good will that existed between Vermeer and his mother-in-law. In Nov. 30 Vermeer and his wife were lent the sum of 200 guilders from Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven, a wealthy Delft citizen and art collector who may have purchased in the following years more than twenty of Vermeer's works. This money may have been a kind of advance payment on the purchase of future works. Van Ruijven is now rightly considered Vermeer's patron. He was almost seven years older than Vermeer and seems to have had a personal relation with Vermeer that went outside the usual client/artist relationship. Feb. the framemaker Anthony van der Wiel, who had married Vermeer's sister Gertruy, registered at the guild as an art dealer. |

| Dutch painting |

Frans Snyders, Flemish painter, dies. Both Pieter de Hooch and Vermeer began to paint the genre interiors refining a regional type, lending it a more realistic qualities of space, light and atmosphere. The Dortrecht landscape artist Aelbert Cuyp borrows warm light and hilly scenery from Italian examples. |

| European painting & architecture |

Diego Velázquez paints Las Hilanderas (The Spinners) The Corsini payed Guercino 300 ducats for the Flagellation of Christ painted in 1657. Guercino was remarkable for the extreme rapidity of his execution—he completed no fewer than 106 large altar-pieces for churches, and his other paintings amount to about 144. In 1626 he began his frescoes in the Duomo of Piacenza. Guercino continued to paint and teach up to the time of his death in 1666, amassing a notable fortune. |

| Music | Le Sieur Saunier: Vencyclopdie des beaux esprits, believed to be first reference book with "encyclopédie" in its title. |

| Literature | |

| Science & philosophy |

A pendulum clock was designed by Christiaan Huygens and built by Solomon Coster. Universal Mathematics (Mathesis Universalis) by John Wallis amplifies the English mathematician's system of notation, applying it to algebra, arithmetic and geometry. Wallis will be credited with inventing and introducing the symbol for infinity; he has demonstrated the utility of exponents, notably negative and fractional exponents. |

| History |

Mar 23, France and England formed an alliance against Spain. Jun 1, 1st Quakers arrived in New Amsterdam (NY). A 4-year Dutch-Portuguese war begins over conflicting interests in Brazil, but Johan de Witt will end the hostilities with a peace advantageous to the Dutch. Coffee advertisements at London claim that the beverage is a panacea for scurvy, gout and other ills. Public sale of tea begins at London as the East India Company undercuts Dutch prices. The Flushing Remonstrance written to Nieuw Amsterdam's governor Peter Stuyvesant December 27 is probably the first declaration of religious tolerance by any group of ordinary citizens in America. The first London chocolate shop opens to sell a drink known until now only to the nobility. |

Vermeer's beginnings

Before Vermeer began focusing primarily on his now-iconic interiors, he dabbled in a variety of motifs and styles. He created two Biblical themes (one is missing), two motifs from classical mythology (another missing piece) and a bordello scene, a prevalent genre in the 1620s and 1630s. Following these ventures, he delved into the so-called "modern" style, characterized by painting a few select figures in affluent contemporary settings with utmost precision. The first of this kind is A Maid Asleep.

Given the diverse themes and techniques in these initial works, Vermeer expert Walter Liedtke believed that no clear indication of a singular master's influence exists. He stated, "If a newly found document disclosed that Vermeer, in his mid or late teens, had trained under a specific artist, it wouldn't shed much light. A closer relationship between teacher and student might have limited Vermeer's capacity to draw inspiration from varied sources and to intuitively link them. Maybe these skills were honed not just as a trainee but also as the son of an art dealer."

First efforts in a new genre

The present work marks Vermeer's foray into the genre interior mode of painting. Genre interior paintings seemingly illustrate scenes from daily life. Though "genre" is a French term that translates to "type" or "sort," its association with art didn't establish until the late 19th century. In the 17th century, these paintings occasionally went by the general descriptor beeldeken—translating to "paintings with small figures"—but were more often identified by their specific content. Coortegardjes, for instance, capture soldiers in leisure or recreation, and conversaties depict stylish young individuals socializing, dining and playing instruments. Genre paintings also commonly represented settings like taverns, kitchens, bustling markets and celebratory events including weddings, births and holidays.

The opening page of Houwelijk

1625

Jacob Cats

Many genre pieces took inspiration from prevalent sayings or illustrative books. A prime example is Jacob Cats' widely read Houwelijk (On Marriage) which debuted in 1625. Contemporary records suggest it sold around 50,000 copies. This publication offered guidance on women's behavior from youth through widowhood to their eventual passing.

Emblem books emerged as another favored type of "wisdom literature," providing insights on the appropriate behaviors encompassing life's myriad facets—ranging from romance and child-rearing to financial, societal and spiritual duties. These volumes distilled an idea into a visual representation and succinct phrase, further elaborated by a corresponding poem.

A secret key?

In the mid-1650s, Vermeer joined contemporary genre painters such as Gerrit ter Borch, Nicolaes Maes and Gabriel Metsu in depicting domestic interiors. He shared their interest in edifying or didactic themes, often supported by emblematic elements. The extent to which Vermeer imbued A Maid Asleep with iconographic significance remains a topic of speculation.

Seymour Slive proposed that the painting serves as a caution against the pitfalls of excessive drinking, citing the overturned römer or Roemer glass and the half-filled wineglass on the table. He gave little weight to the Cupid depicted above the girl's head. Conversely, Madlyn Millner Kahr interpreted the painting as symbolizing disillusioned and unrequited love, as evidenced by the maid's despondent posture.

Peter L. Donhauser offered a different perspective, suggesting the painting's focal point lies in a subtle detail: what seems to be the ring of a key on the near edge of the open door. Both visual and literary sources from that era associate keys with domestic responsibility, duty and loyalty, emphasizing the notion of exclusive access. Keys are closely tied to housewives and maids. Furthermore, keys bear a sexual undertone, hinting at either lascivious behavior or feminine chastity. Notably, Nicolaes Maes, Samuel von Hoogstraten and Jan Steen used the key as a metaphor for emphasis—a literal clavis interpretandi—to spotlight a detail pivotal to comprehending a painting. Vermeer might have incorporated this motif with similar intent.

The Slippers

Samuel van Hoogstraten

Between 1654 and 1662

Oil on canvas, 103 x 70 cm.

Louvre, Paris

A few keys are featured so prominently in a domestic interior as Samuel van Hoogstraten's The Slippers.

In the 17th-century Netherlands, the production of keys was primarily a manual process involving blacksmiths and specialized locksmiths. The methods of key and lock production had been evolving since ancient times, but the basic principles remained consistent. The key's basic shape was forged using a hammer and anvil. Blacksmiths or locksmiths would heat a piece of iron or steel until it was red-hot, making it malleable. The smith would then shape the metal into the form of a key, creating the bit (the part of the key that interacts with the internal mechanisms of the lock) based on the design of the lock it was intended to open. To make the key more durable, it was often reheated and then quenched in water or oil. This process, called hardening, would ensure that the key did not deform or break easily in use.

As Urbanization increased, and with it, the need for security. Locks and keys were no longer the sole domain of the wealthy or the elite; they became commonplace items found in urban households and businesses.

Interpreting the hidden meaning of genre painting

The Idle Servant

Nicolaes Maes

1655

Oil on oak, 70 x 53 cm.

National Gallery, London

In the early part of the 17th century, genre paintings often had clear allegorical content. They warned of the vanity of worldly pleasure, the dangers of vice, the perils of drink and smoke, the laxness of an old woman or the sloth of a maid. Genre painting both reflected upon and defined ideals about family, love, courtship, duty and other life aspects. By mid-century, most genre pictures had become less overtly didactic.

A key to understanding the girl's attitude is found in the catalog description of the 1696 sale of the painting as "a drunken, sleeping maid at a table." In fact, on the table before her are not one but two glasses—one standing with a bit of white wine, and another, darkish römer glass typically used by men laying downward in front of it—and a wine jug. Originally, there were also some grape leaves to the left side of the still life, later removed by the artist. Today, neither glass is immediately visible. Perhaps the woman's glass was deliberately concealed, but the overturned römer might have been obscured by time or careless cleaning.

The Idle Servant (detail)3

Nicolaes Maes

1655

Oil on oak, 70 x 53 cm.

National Gallery, London

However, this traditional interpretation of A Maid Asleep has been challenged by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. He concludes that the young girl's pose "does not indicate that she is asleep, nor does it mirror sloth in Maes' painting (The Idle Servant, the clear model for Vermeer's composition). In this context, the girl's pose may allude to another iconographic tradition in which a figure rests its head on its hand: melancholia. In the 17th century, melancholia was often linked to depression, introspective reflection, artistic creativity and unhappy love affairs." For Wheelock, the cause of the young girl's distress is revealed within the painting. The visible portion of the painting behind her, though small, is sufficient to associate it with a contemporary emblem about the serenity of love and overcoming deceit.

The missing cavalier & dog

During the painting process, Vermeer revised his initial concept of the present work, which, as described by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., was composed of two isolated vignettes the foreground with the sleeping maid and the background with an empty room

X-radiographs show that the artist initially intended to include more elements in the narrative. He had painted a dog in the doorway that gazed at a standing man wearing a broad-rimmed hat in the farthest part of the back room. Additionally, grape leaves covered the fruit in the current still life, and the chair in the foreground was later added, limiting the view into the distant room. While it was previously known that a male figure existed in the painting, his role in the scene have been largely speculative. Some suggest that, given this male presence, the painting might have depicted a seduction scene, a recurring theme in Vermeer’s works. However, recent non-invasive research conducted by Met conservator Dorothy Mahon and research scientist Silvia Centeno has unveiled the figure in more detail. Using X-ray fluorescence, it's now evident that the man seems to be reaching out as if holding a paintbrush, and the previously thought door was, in fact, an easel.

Vermeer also trimmed the picture on all sides, emphasizing the central figure in relation to its surroundings. These changes highlight his preference for a more poetic image over narrative clarity, providing the viewer with more room for personal interpretation. By streamlining the composition, he focused on the main elements, removing any potential distractions.

It was previously known that a male figure existed in the painting. The identity of this man and his role in the scene have been largely speculative. Some suggest that, given this male presence, the painting might have depicted a seduction scene, a recurring theme in Vermeer’s works. However, recent non-invasive research conducted by Met conservator Dorothy Mahon and research scientist Silvia Centeno has unveiled the figure in more detail. Using X-ray fluorescence, it's now evident that the man seems to be reaching out as if holding a paintbrush, and the previously thought door was, in fact, an easel.

Maid or mistress?

For many art historians, attributing a precise iconographic meaning to a painting by Vermeer can be challenging, with A Maid Asleep being a prime example. In some instances, even the social identity of the sitters themselves has been questioned. While numerous critics have identified the central figure as an inebriated maid, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. posits that, based on her sophisticated attire, she might be more akin to a mistress than a lowly servant. If so, she might not symbolize a lazy maid but rather an upper-class woman grappling with matters of the heart.

That said, her fine clothing doesn't necessarily negate the possibility of her being a maid. The phenomenon of lavishly dressed maids was a known issue in the Netherlands. A 1681 Amsterdam law even prohibited household staff from donning silk attire and accessories like those worn by Vermeer's subject. In mainstream literature of the time, maids were sometimes portrayed as potential risks to the sanctity of the home, a pivotal element of Dutch culture. These domestic workers were often central figures in the era's plays and writings. Simon Schama once noted that 17th-century maids were widely seen as the most perilous women.

Difficulties with iconography

The present picture has been the subject of many interpretative efforts, but none of the explanations have fully addressed all of its features.

While the study of iconography (hidden symbolic meaning) in relation to 17th-century Dutch genre painting has fascinated art scholars throughout much of the 20th century, several questions remain unanswered. It's evident that many Dutch genre painters incorporated symbolic meaning into their pieces, often not immediately discernible to today's audience. However, the extent of this symbolism remains ambiguous. Some painters consistently incorporated hidden symbols into their work, while others did so intermittently, and a few used them only on rare occasions.

Another unresolved question concerns the resources painters referenced when creating their symbols. While there's no analogous guide for genre painters akin to Cesare Ripa's Iconologia—which served as an essential reference of symbols for history painters, enabling them to depict abstract concepts like faith, glory or virtue visually—it's clear that history painters often drew inspiration from Ripa, though not always strictly. In contrast, genre painters infused their pieces with symbolism based on their preferences or the preferences of potential patrons, drawing from popular literature, emblem books and common sayings. Some patrons might have prioritized symbolic meanings, while for others, the appropriate subject matter could have served as a bonus or even a justification. One possible reason for the scant documentation on the symbolic usage in genre painting might be that the meanings were common knowledge during that era. As a result, what was widely understood back then, and not deemed necessary to document, has evolved into a speculative and somewhat uncertain field of study in our times.

Vermeer's pictures have been the subject of ample interpretation but have eluded any clear or consistent explanation. Some of his paintings, like Allegory of Faith, Woman Holding a Balance and The Art of Painting, appear steeped in traditional symbolism. In contrast, others seem to focus solely on the visual narrative. Some experts believe that Vermeer utilized the multifaceted nature of contemporary symbols to infuse his paintings with poetic depth, allowing the interpretation to vary based on individual viewer perceptions.

The doorway in Dutch painting

View of an Interior, or The Slippers

Samuel van Hoogstraten

between 1654 and 1662

103 x 70 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Within the history of Western art, the door symbolizes both physical and metaphysical transformation. In Dutch genre painting of the mid-17th century, this visual interest in the door seems to have reached its zenith. Indeed, the fascination with Dutch genre paintings seems almost obsessive.

As art historian Georgina Cole noted, by the 1650s and 60s, doors—doorways, open doors, half-open doors and even closed doors—are prominent in paintings across each province and in the work of nearly every recognized genre painter. They are frequently depicted in the interior paintings of artists like Pieter Saenredam, Emmanuel de Witte, Nicolaes Maes, Jacob Ochtervelt, Pieter de Hooch and Samuel Van Hoogstraten, leading to streets, courtyards and other rooms. Vermeer is known to have painted at least three interiors featuring doorways."

The influence of Vermeer on 20th-century cinema cannot be overstated. His masterful use of light and shadow, paired with his unique composition techniques, offered a visual vocabulary that many filmmakers sought to emulate. By the 1940s, filmmakers began referencing Vermeer's compositions through the mise-en-scène, framing views through doorways similar to those in The Love Letter or positioning solitary women near a window. A pioneer in this respect was the silent film director D.W. Griffith, who, in his 1919 film Broken Blossoms, utilized Vermeer-like interior shots with soft lighting to underscore the poetic mood of the narrative. Greenaway's film The Draughtsman's Contract (1982) is rich with visual references to classical paintings, including those of Vermeer. The film often captures the essence of Vermeer through its use of light, framing and composition.

Certain compositions in Jean-Pierre Jeunet's Amélie evoke the atmosphere and style of Vermeer's paintings. One particular scene with Amélie standing by the window mirrors the positioning of women in many of Vermeer's works.

A mask of deceit?

Critics generally agree that so-called pictures-within-pictures found in many Dutch genre paintings of the time were meant to convey comment on the scene which takes place below. The interpretation of the present picture has been particularly problematic. The painter and art historian Lawrence Gowing supposed that the inclusion of the mask in the Cupid painting (the Cupid's left-hand foot can barely be made out) illuminates the theme with a typical reference; sleep admits a fantasy of love.

If the fallen mask were to signify deceit, rather than being drunk the young girl may be feigning sleep to her lover who is about to appear. In fact, Vermeer had once painted a standing cavalier in the back room, seen through the door, but at one point or another during the painting process painted it out.

The Cupid was apparently inserted as a picture-within-a-picture three other times: in the Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, where it was painted out by Vermeer, the Girl Interrupted in her Music and in the late Lady Standing at a, where it can be seen in all its unabashed boldness. Most art historians believe that the now-lost painting is a work by the classicist Cesar van Everdingen, whose putti are similar to that of Vermeer's Cupid. To be noted is the fact that in all three other paintings the mask of the Cupid is absent.

Listen to period music

![]() Nicolas Vallet (c. 1583-c.1642)

Nicolas Vallet (c. 1583-c.1642)

Slaep, soete slaep (Sleep, sweet sleep) [2MB]

Konrad Ragossnig, lute

Meaning & money: a patron for Vermeer

Although it may not be apparent to modern museum-goers, most of Vermeer's interiors transport the viewer into situations that do not reflect the culture and social standings of the artist but more likely those of his rich Delft patron, Pieter van Ruijven. A Maid Asleep is considered the first painting to have been acquired by Van Ruijven.

Van Ruijven entertained great ambitions along with his wife, Maria de Knuijt, who was independently rich. In 1669, he paid an exorbitant sum, 16,000 guilders, to acquire land near Schiedam that brought with it the title of Lord of Spalant. He built himself a respectable art collection and through the years acquired at least 20 works by Vermeer (at least one-third of the artist's estimated output) and stipulated a conspicuous sum of 500 guilders to the artist in his will, an exceptional bequeath for the time. Since the works he collected evenly span the arc of Vermeer's activity, it seems that he acquired about one important work each year perhaps through a first-option agreement. Historians believe that Van Ruijven may have taken the lead from his cousin Pieter Spiering Silvercroon who was a patron of Gerrit Dou, one of the best remunerated painters of the century.

Thus, in their symbiotic relationship Vermeer's art might have been considered a means by which Van Ruijven could not only cultivate his love of art but, like the great mecenas of the Italian Renaissance, raise his social rank and carve himself a place in history by associating his name with that of a great artist. Likewise, Vermeer's elaborate Art of Painting, whose central theme is the glory and fame brought by art, demonstrates that his artistic ambitions paralleled his patron's desires for fame and social elevation.

Vermeer's relationship with Van Ruijven could have brought him other advantages. For example, in the Netherlands, where painters sold their works through myriad channels, from auctions and dealers' shops to fairs and lotteries, the most innovative and expensive art that Vermeer would have wanted to study was accessible through private channels, channels which Van Ruijven could have opened.

View of an Interior, or Art-lovers in a Painter's Studio

Pieter Codde

c. 1630

Oil on panel, 38 x 49 cm.

Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart

To what degree Vermeer tailored his works to Van Ruijven's expectations is unknown but a collaborative relationship would be neither surprising nor anomalous. What did Vermeer and Van Ruijven discuss? Most likely they conversed on art theory and the artistic developments in the Netherlands, which had one of the most florid and innovative art markets of Europe. Obviously, Van Ruijven desired beautiful paintings but paintings that were important as well. The fact that Vermeer was able to concentrate his efforts on a few near-perfect paintings may be the consequence of Van Ruijven's financial support and their shared vision of art.

While Vermeer must have been fully in charge of the aesthetic part of his art, Van Ruijven would not have refrained from suggesting some moral concept that would have had a personal significance, or else a successful motif of another artist that appealed to his tastes. However, since Vermeer did not depict his own world it could be that it was Van Ruijven who offered guidance to the painter.

Lest our modernist sensibilities be offended by the notion of close collaboration between artist and client, we should remember that the overwhelming number of great European paintings was the fruit of commissions. The client furnished the work's subject (often indicating a specific textual source), dimensions, materials and even certain aspects of its composition. Essentially, it was the artist's task to bring to life the motif which reflected the cultural aspirations of the commissioner.

Vermeer's "love affair" with Cupid

Cupid Preparing His Bow

Jacob Huysmans after Anthony van Dyck

between 1650–1696

Oil on canvas,

Private collection

Cupid, known as Eros in ancient Greek mythology, is the god of desire, erotic love, attraction, and affection. He has been a favorite subject of artists since ancient times. The motif of Cupid was popularly used in Baroque painting, either by itself or in various mythological scenes. In Vermeer's paintings, he appears—either partially or fully—four times as a picture-within-a-picture.

Cupid Holding a Glass Orb

Caesar van Everdingen

c. 1655–1660

Oil on canvas,

Private collection

As has often been noted in Vermeer literature, "a Cupid" could mean either a statue or a painting of the winged god of love. The painting that Vermeer used as a model was first attributed by German art historian Gustav Delbanco in 1928 to Caesar van Everdingen, a Dutch Golden Age portrait and history painter who painted numerous depictions of similarly proportioned naked putti (nude child figures, often with wings). Based on the chronology of Vermeer’s paintings, the inclusion of the same Cupid four times, albeit with slight variations, over a 15-year period makes it highly probably that Vermeer had this work in his home. This is reinforced by the fact that the probate inventory of Vermeer’s estate, compiled in 1676, two months after his death, mentions an artifact "from the upstairs backroom" referred to as "Cupid," which could be this painting.

Art historians have tried to track Vermeer's Cupid in the vast history of auctions and sales of art, but it has proved impossible to find. Interestingly, based on Vermeer canvases, they tried to estimate the size of the real Cupid painting – it should be approximately 115 x 85 cm, which is quite large.

Another question is: what did Vermeer wish to convey with the now-lost Cupid? Did its meaning change according to its context? Numerous art historians and Vermeer experts such as Walter Liedtke, Aurthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Gregor Weber have attemtped furnish plausable explanations. However, as Weber pointed out, the exact meaning Vermeer intended may be elusive, but the deliberate alterations in how he portrayed the Cupid across different works were likely intended to give a more nuanced meaning to the scene unfolding in the foreground. Perhaps this kind of puzzle would have delighted a 17th-century audience familiar with the similar emblematic images that abounded in emblematic literature.

In A Maid Asleep, although barely visible in reproductions, Cupid strides forth "triumphantly," trampling over two masks cast upon the ground. Perhpas the cause of the "dozing" (tipsy?) maid's condition is in fact, Cupid's working.

Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

Johannes Vermeer

In the Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, Cupid tramples on a mask, a motif not seen in the Late Lady Standing at a Virginal. Here, the mask is a readily understood metaphor for deceit. In other words, in matters of the heart, Cupid rejects deceit in favor of sincerity.

In the Girl Interrupted in Her Music, the inclusion of the standing, nude god of love underscores the amorous nature of the encounter between the lady and her company. Because it was overpainted in the past and subsequently restored, the paint layer of Cupid is severely abraded. Originally, it would have been easier to discern how Cupid seems to comment on the man’s seductive wiles from behind the latter’s back. Both the woman and Cupid peer at the viewer, drawing them directly into Vermeer’s painted scene.

A Lady Standing at a Virginal

Johannes Vermeer

In the last depiction, in Lady Standing at a Virginal, Cupid is pictured standing, rendered in lighter, airier tones than in the preceding versions. He holds a blank card, reminiscent of the Cupid in another emblem from Otto van Veen’s popular "Amorum emblemata." However, there, Cupid holds a tablet inscribed with the number "1." Meanwhile, with his foot, he tramples on the numbers 2 to 10 on another tablet. The caption explains that true love can be directed to "one person alone." Strangely, no mask appears at his feet in Vermeer's work.

Scholars have been unable to explain precisely why Vermeer would have included the Cupid so frequently in his own works, especially considering he must have had many other works to choose from that he traded, like many artists of the time, to supplement his income.

Whatever the Vermeer's intentions, the painted Cupid belongs to the pictorial tradition of portraying a full-figure, life-size Cupid alone, combined with symbolic gestures and motifs. Other great painters from this time, such as Rembrandt, who painted Cupid blowing a bubble in 1634, popularized this motif. The little god of love was also often presented with a golden balance, a pair of scales, and, of course, wings.