- Click here to view a sortable table of all past, ongoing, and future Vermeer exhibitions.

EV website addition: the 1689 Reis-Boek door de Vereenigde Nederlandtsche Provintien

Amsterdam

Jan ten Hoorn

1689

A new lushly illustrated study on Essential Vermeer examines how Delft was described to travelers in afascinating late-seventeenth-century guidebook published just fourteen years after Vermeer’s death. Focusing on the Delft section of the 1689 Reis-Boek door de Vereenigde Nederlandtsche Provintien (full title: Travel Book through the United Netherlands Provinces, and Their Neighboring Regions and Kingdoms; Containing a Precise Description of the Cities, with Indications of the Boat and Wagon Routes, along with Suitable Inns Where Travelers May Lodge in Each City, and Other Useful Travel Information), the article reconstructs the city as visitors encountered it in Vermeer’s lifetime: its churches, civic buildings, markets, inns, and remarkably precise transport schedules. Read alongside paintings such as View of Delft and The Little Street, the guide reveals a city shaped by order, mobility, and civic routine, offering a grounded historical framework for understanding the everyday world behind Vermeer’s quiet scenes.

Temporary Closure of the Mauritshuis

The Mauritshuis in The Hague will temporarily close for building renovations from August 24 to September 20, 2026. The collection houses three paintings by Vermeer: View of Delft, Girl with a Pealr Earring, and Diana and her Companions. The iconic Girl with a Pearl Earring, will be loaned to Japan for an exhibition at the Nakanoshima Museum of Art in Osaka (see item below). This closure coincides with a rare international loan of its key masterpiece, allowing Japanese art lovers to see it while the museum undergoes necessary building work.

Key Details:

- : August 24–September 20, 2026.

- : Building renovations.

- : During this period, Girl with a Pearl Earring travels to Japan.

- : The painting will be at the Nakanoshima Museum of Art in Osaka from August 21 to September 27, 2026.

Girl with a Pearl Earring goes to Japan

Girl with a Pearl Earring

Nakanoshima Museum of Art

, Osaka

August 21-September 27, 2026

https://vermeer2026.exhibit.jp/

Art lovers will have chance to see Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring in Japan, which will be displayed at the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka from Aug. 21 to Sept. 27.

The exhibition will be organized by The Asahi Shimbun, the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka, and Asahi Television Broadcasting Corp. The painting’s trip to Japan will be its first in 14 years since 2012 when about 1.2 million people visited the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum for the Masterpieces from the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis exhibition, which was also organized by The Asahi Shimbun, among other entities.

Johannes Vermeer's painting "Girl with a Pearl Earring" will be displayed in Japan later this year, the Dutch Mauritshuis museum said Thursday, a rare outing abroad for one of the world's most famous artworks.

- Further details will be announced in late February.

- Exhibition inquiries will open in late February.

- Vermeer's masterpiece will be loaned to the Nakanoshima Museum of Art in Osaka while its home museum in The Hague is closed for renovations.

- This exhibition will be held only in Osaka and will not travel to other regions.

Martine Gosselink, general director of the Mauritshuis: "The Asahi Shimbun has been a highly valued partner of our museum since the major revamping of the Mauritshuis between 2012 and 2014. The Asahi Shimbun organises several exhibitions each year with museums around the world. We are highly honoured to be able to work with the media organisation on the presentation in Osaka in 2026. Every year, we welcome thousands of Japanese tourists who love Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring. For the Mauritshuis, the Girl’s trip to Japan is a unique opportunity for us to share her with the Japanese public, perhaps for the very last time."

Girl with a Pearl Earring went on a world tour while major building work was being carried out at the Mauritshuis in 2012–2014. The touring exhibition provided important funding for the renovations. In Japan, the painting was shown at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum and in the city of Kobe. It then moved on to the United States for the exhibition The Masters of the 17th Century: Dutch Painting from the Mauritshuis. A total of 2.2 million people visited the touring exhibition.

A rare jewellery box and other objects identified in Vermeer paintings sheds new light on the artist's connections in a new book about the tangible objects in Vermeer's paintings

De tastbare wereld van Johannes Vermeer: Huisraad als schildersmodel (The tangible world of Johannes Vermeer)

Alexandra van Dongen

https://www.bol.com/be/nl/p/de-tastbare-wereld-van-johannes-vermeer/9300000233085375/

Alexandra van Dongen

A forthcoming Dutch publication by Alexandra van Dongen, curator at the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, reveals that the ornate jewellery casket seen in Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid and A Lady Writing was an Indo-Portuguese work produced in 17th-century Cochin, India. Crafted from teak and ebony, such caskets were luxury items commissioned by Europeans and are now exceedingly rare. Van Dongen, aided by Amsterdam art dealer Dickie Zebregs, traced what may be the only surviving example in the Távora Sequeira Pinto collection in Porto. Since Vermeer could scarcely have afforded such a costly object, the study suggests that the casket was likely lent to him by his patron Maria de Knuijt, a wealthy shareholder in the Dutch East India Company and owner of both paintings.

Van Dongen’s research highlights Vermeer’s careful observation of real objects, from precious imports to everyday items. In Woman with a Pearl Necklace, she identifies another Asian luxury—a Japanese lacquer box with gold decoration, possibly also owned by De Knuijt—while The Milkmaid features an Oosterhout earthenware pot, a humble kitchen vessel typical of Delft households. Together, these discoveries underline Vermeer’s fascination with the tangible world that surrounded him and his ability to render both the exotic and the ordinary with equal precision and reverence.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1666–16687

Oil on canvas, 90.2 x 78.7 cm.

Frick Collection, New York

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1667

Oil on canvas, 45 x 39.9 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

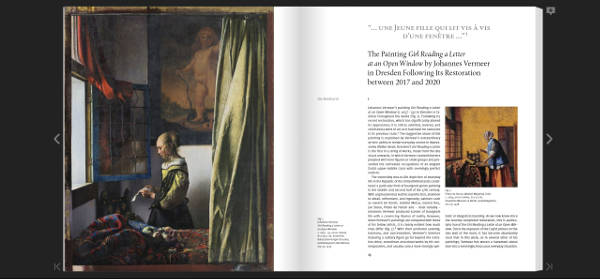

Brand new Vermeer publication on Vermeer's Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

Johannes Vermeer. Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window: Restoration and Studies in Painting Technique

Uta Neidhardt and Christoph Schölzel

August 8, 2025

144 pages, 222 illustrations

https://verlag.sandstein.de/detailview?no=98-814

:

Johannes Vermeer’s painting Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window is familiar to a worldwide audience and is admired and revered. However, the restoration carried out between 2017 and 2021 has significantly changed its appearance. The spectacular removal of a later overpainting in the background of the painting brought to light the depiction of a god of love, which must now be linked to the figure of the letter-reading girl again as a picture within a picture. This suggests a new interpretation of the painting that had been concealed for centuries: the god of love functions as a meaningful commentary on the scene, which the viewer now clearly perceives as an amorous situation. In the painting, the composition, light and color mood and aura have changed fundamentally.

This publication contains the results of research and investigations that examine the restored painting from the perspective of the team of European and American institutions from the fields of restoration, natural sciences, art history, mathematics and IT that worked together on a four-year project. It is intended to contribute to an even more comprehensive description of Vermeer’s painting, to clarify the process of its creation and to make the Dresden decision to accept the later overpainting transparent and comprehensible to experts and the public.

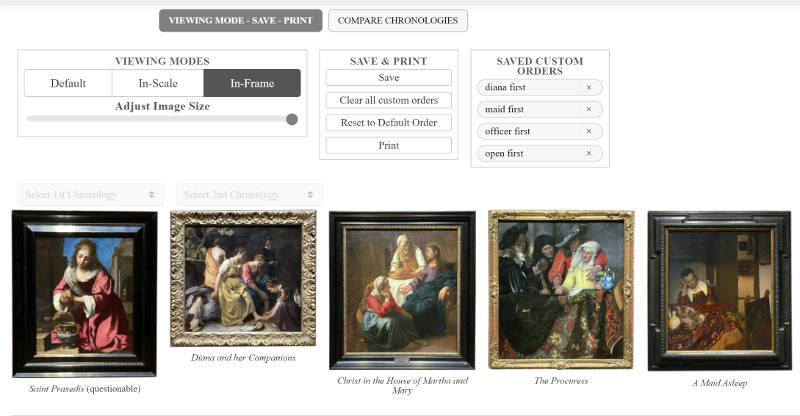

Essential Vermeer addition: Vermeer Chronology: An Interactive Feature

Chronologies are vital instruments in art history, as they make it possible to trace an artist’s evolution, follow changes in style, and reconstruct the order in which ideas and techniques emerged. For Vermeer, this task is unusually complex, since only two of his thirty-five (?) paintings are dated. Every proposed sequence is therefore partly conjectural. Yet, despite the scarcity of evidence, most scholars have arrived at a general agreement about the relative order of his works.

The newly updated Essential Vermeer chronology expands the traditional horizontal display of paintings into a dynamic, interactive tool for both newcomers and specialists. Users can view the paintings in three modes—standard, in-scale, and framed—resize and scroll through each sequence, create and save up to five custom orders, and compare them directly with the chronologies of seven leading Vermeer scholars or the default Essential Vermeer order. Paintings considered doubtful or rejected are grouped at the end for clarity. Custom sequences can also be printed in a grid layout, offering an engaging way to visualize and test different interpretations of Vermeer’s artistic development.

The same Vermeer side by side

Double Vision: Vermeer at Kenwood

September 1, 2025–January 11, 2026 (10am–5pm)

Kenwood House, Hampstead

Kenwood House will host an exceptional display bringing together two versions of Vermeer's treasured Guitar Player, yet scholars have long debated whether a second version in the Philadelphia Museum of Art is an autograph work by Vermeer or a close contemporary copy.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1673

Oil on canvas, 53 x 46.3 cm.

Iveagh Bequest, London

Johannes Vermeer ?

c. 1670–1672

Oil on canvas, 53 x 46.3 cm.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection, Philadelphia

The PMA acquired The Guitar Player (Lady with a Guitar) from the John G. Johnson Collection in 1933, but only in recent years placed it on view for the first time. Long considered a possible Vermeer, doubts arose after a better-preserved version surfaced in London, leading some experts to dismiss the damaged Philadelphia work as either a copy or a secondary version. The painting had suffered from harsh cleaning, a failed 1973 restoration, and a significant tear. In 2016, conservator Arie Wallert initially rejected it as a Vermeer after detecting traces of Prussian blue, a pigment developed after the artist’s death, but later studies in 2021 identified authentic seventeenth-century pigments, suggesting the supposed Prussian blue was likely indigo. These findings reignited debate about the painting’s attribution, prompting the museum to display the work unrestored while inviting scholars and the public to follow its ongoing technical investigations.

For the occasion, Kenwood has prepared an excellent scroll-triggered animation webpage that investigates in depth the two paintings’ techniques and materials, allowing even the untrained visitor to grasp the questions surrounding the authenticity of the PMA canvas and offering the context needed to form a personal judgment.

Through scientific study and conservation analysis, researchers have examined the construction, pigments, and materials of both canvases in an effort to resolve this longstanding question. Visitors to Kenwood will now have the rare opportunity to see the two paintings side by side and consider the evidence themselves.

Because of its fragility, the Kenwood Guitar Player remains unlined and still rests on its original 17th-century stretcher, the work did not travel to the Rijksmuseum's major Vermeer exhibition in 2023. This presentation offers an unprecedented comparison in London.

Admission is free and unticketed. The paintings will be on view together in the dining room lobby of Kenwood House.

:

Wendy Monkhouse

Essential Vermeer website addition: Historical Value of the Guilder: Measuring Vermeer’s Prices in Context

Historical Value of the Guilder: Measuring Vermeer’s Prices in Context

https://www.essentialvermeer.com/references/vermeer-economy.html

This new illustrated study examines how money, value, and art intertwined in the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic. It explains the structure of the Dutch monetary system—how coins were valued by their metal content rather than by government decree—and the crucial role of the Amsterdam Wisselbank in stabilizing exchange and sustaining the Republic’s vast commercial network. Through tables, paintings, and period sources, it traces the shifting intrinsic and purchasing value of the guilder from Vermeer’s lifetime through the eighteenth century, situating his prices and income within the broader context of the Dutch economy.

The essay also explores what a guilder could buy in daily life—food, housing, clothing, and wages—and compares these costs with the market for paintings. Drawing on documentary evidence from guild records, estate inventories, and auctions, it reconstructs how painters such as Vermeer, Gerrit Dou, and Frans van Mieris earned their living, what their pictures sold for, and how artworks functioned as both commodities and instruments of exchange. The study offers a richly contextualized picture of the economic world behind Vermeer’s art, where value, trust, and craftsmanship were inseparable.

Vermeer's life and work reinterpreted by Andrew Graham-Dixon

Vermeer: A Life Lost and Found

Andrew Graham-Dixon

23 Oct., 2025

:

The paintings of Johannes Vermeer of Delft are some of the most beautiful, even sublime, in the history of art. Yet like the life of Vermeer himself, they are mysterious and have for centuries defied explanation. Following new leads, and drawing on a mass of historical evidence, some of it freshly uncovered in the archives of Delft and Rotterdam, Andrew Graham-Dixon paints a dramatically new picture of Vermeer, revealing many of the painter’s hitherto unknown friendships as well as his previously undetected allegiance to a radical movement driven underground by persecution.

He also vividly evokes the world of the Dutch Republic as it was in its so-called Golden Age. This was a watery world of fortresses and flood plains, taverns rocked by argument and cities stunned by devastating attacks and explosions: all linked by a network of canals where a uniquely efficient public transport system, operated by horse-drawn passenger barge, enabled people, goods and ideas to glide effortlessly from one place to another. The author sets Vermeer firmly in the context of his time, revealing the patterns of patronage that make sense of his work, and also exposing the difficulties posed by his home life, which was dominated by his Jesuit mother-in law and disturbed by the psychotic behaviour of her only son.

In the past Vermeer has been imagined as a remote and enigmatic figure, but he emerges from this new account as a man deeply engaged with his own society: well-travelled, a reader of books, a man personally connected to many of the most interesting people of his time, including merchants, philosophers, preachers, bankers and regents, as well as his childhood friend, a philanthropic baker named Hendrick van Buyten. Vermeer was also deeply affected by the struggles that shook his world, the Eighty Years War for Dutch independence and the yet more terrible Thirty Years War, which ravaged the neighbouring German lands and resulted in the deaths of millions. The author shows how he was moved to become a pacifist by such atrocities, and thereafter made many of his closest friends in the ranks of Europe’s first peace movement. A further revelation is that Vermeer’s closest collaborator and chief patron was a woman, as were many others in his immediate circle. These are all previously untold stories.

The many piercingly direct descriptions of Vermeer’s pictures, which are the heart of the book, shed new light on the intentions of the artist. Nearly all of his best loved works, Graham-Dixon shows, were originally painted for a single significant location in Delft. In light of such discoveries every one of Vermeer’s major paintings, including The Girl with a Pearl Earring, A View of Delft and The Milkmaid, are reassessed and their meanings rethought. As a result the two great unresolved questions about Vermeer – why did he paint his pictures, and what do they mean? – are persuasively answered here for the first time.

New Vermeer-related publication: Vermeer's Love Letters

Vermeer's Love Letters

April 29, 2025

Robert Fucci

April 29, 2025

Robert Fucci

The theme of writing and receiving letters, a subject that recurs frequently in the work of Johannes Vermeer, is given dramatic tension in three iconic paintings in which elegantly dressed women eagerly await correspondence, subtly hinting at themes of love and longing.

Centered on the motif of letter writing, this book unites three iconic Vermeer paintings—Mistress and Maid (The Frick Collection), The Love Letter (Rijksmuseum), and Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid (National Gallery of Ireland)—delving into the enigmatic allure of the Dutch painter's work. Vermeer’s artistry is renowned for encapsulating moments of intrigue and intimacy amidst the domestic scenes of Dutch life. Through masterful manipulation of light and perspective, he imbues his paintings with symbolic depth, exploring themes of communication, secrecy, and emotional connection.

Through meticulous analysis, this publication explores the profound thematic undercurrents binding these masterpieces, shedding light on Vermeer’s legacy and his ability to capture moments of intimacy with unparalleled depth. Examining the implied and explicit meanings of the works, the publication offers a scholarly dialogue between past and present interpretations, questioning whether the works serve as complex allegories or straight-forward depictions of Dutch upper-middle-class life. Additionally, other paintings by Vermeer, Gerrit ter Borch, Gabriel Metsu, and Rembrandt are explored, addressing the relevance of their comparable images and offering a fresh perspective on the enduring relevance of Vermeer’s artistry.

Click here to purchase at Amazon.com

Art Newspaper uncovers long-suppressed details of 1968 attack on Vermeer’s Young Lady Seated at a Virginal

"Vermeer’s vandal: the untold story of a vicious attack at London's National Gallery in 1968"

Art Newspaper

September 2, 2025

Martin Bailey

In March 1968, Vermeer’s Young Lady Seated at a Virginal suffered a nearly disastrous attack at London’s National Gallery. A vandal, never identified, used a sharp blade to cut around the head of the sitter, apparently intending to remove it entirely. Had the attempt succeeded, the damage would likely have forced the painting into permanent retirement, reducing Vermeer’s already small surviving oeuvre. The head was only saved because the blade failed to penetrate the canvas fully, perhaps due to a recent relining. Although a visitor noticed the vandalism soon after it occurred, it went unreported for nearly two hours before staff were alerted.

The trustees decided against releasing photographs of the damage, fearing that they might encourage the attacker or draw unwanted publicity. The gallery issued only a minimal statement, assuring the press that the work could be restored without "grave problem." In fact, the cuts had reached between the sitter’s eyes and left deep scratches elsewhere. Conservators quickly relined and retouched the painting, and it returned to view just three weeks later, now shielded with protective glazing. For decades the severity of the incident remained virtually unknown, receiving scant mention in Vermeer scholarship until these photographs were recently revealed.

Vermeer's Girl with a Flute on view again at the NGA

After a prolonged absence, Vermeer’s Girl with a Flute is once again on display at the National Gallery of Art, West Building, Main Floor, Gallery 50-A according to the gallery website.

Following two years of research into the four paintings attributed to Vermeer in 2022, the Gallery had downgraded the work's status to "Studio of Johannes Vermeer" and had temporarily removed it from public display.Marjorie E. Wieseman, Alexandra Libby, E. Melanie Gifford, Dina Anchin, "Vermeer’s Studio and the Girl with a Flute: New Findings from the National Gallery of Art," Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 14:2 (Summer 2022) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2022.14.2.3

:

Studio of Johannes Vermeer

Dutch, 1632–1675Girl with a Flute, c.1669/1675

oil on panel

Widener Collection 1942.9.98A young woman gazes out from beneath the shadow of her large, striped hat. Her pose, expression, clothing, and surroundings resemble those seen in paintings by Johannes Vermeer. In 2020–2021, however, a team of National Gallery of Art researchers—curators, conservators, and scientists—determined that Vermeer did not paint Girl with a Flute. The artist who created this work was intimately familiar with Vermeer’s materials and techniques but was unable to match his delicate brushwork. Who, exactly, might have painted this engaging work remains an open question.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1665–1670

Oil on panel, 20 x 17.8 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington

EV addition: An extensive glossary of art terms: Essential Vermeer Pulldown Glossary of Art Terms

Essential Vermeer Pulldown Art Glossary

https://www.essentialvermeer.com/glossary/glossary-pulldown.html

Other than a pulldown menu for quick reference, there is also a fully displayed conventional HTML version accessible here for continuous reading and exploration.

Art is full of specialized language that can be puzzling to the lay reader. Many terms used by artists, historians, and critics have meanings that differ from their everyday usage, while others are so specific to the field that they are virtually unknown outside of it. This online glossary is dedicated to clarifying these distinctions, offering clear definitions and historical context. Each entry begins by examining the term within the broader history of art, tracing its development, significance, and various interpretations across time and cultures. When relevant, the discussion then shifts to its specific role within the Dutch Golden Age, a period that saw an unprecedented flourishing of artistic innovation, market-driven production, and technical refinement. The glossary highlights how these concepts were understood and applied by Dutch painters, collectors, and theorists, situating them within the broader intellectual and social currents of the time.

Given the focus of this website, the glossary also includes a dedicated section within applicable entries that explores how each term relates to Vermeer's paintings, working methods, or artistic vision. Marked with Vermeer's well-known monogram, this section signals a focused discussion of his unique approach—whether analyzing his materials and techniques or considering his place within Dutch artistic traditions. By structuring the glossary in this way, it serves as both a reference tool and a deeper exploration of artistic practice, bridging general art history with the nuanced particularities of seventeenth-century Dutch painting and Vermeer’s enduring legacy.

With more than 700+ carefully curated terms and a network of over 30,000+ internal links and 500+ images, the glossary allows users to navigate seamlessly across multiple facets of art, revealing unexpected connections and deeper layers of meaning. Designed as both a structured reference and an open-ended exploration, it encourages readers to move beyond isolated definitions, tracing the evolution of artistic ideas across time and disciplines. Whether approached as a scholarly resource or as a guide for enthusiasts eager to deepen their understanding, this glossary provides an extensive and interconnected repository of artistic knowledge.

Other than a pulldown menu for quick reference, there's also a fully displayed conventional HTML version accessible here for continuous reading and exploration.

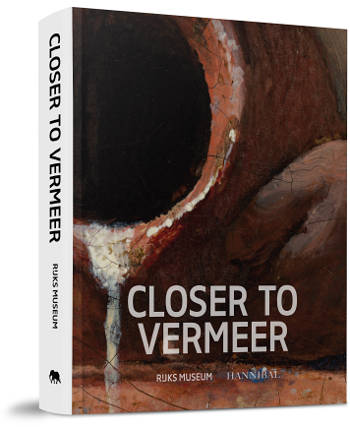

Closer to Vermeer: New Research on the Painter and his Art

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam / Hannibal Books, Veurne

ISBN 978 94 6494 199 9

432 pages

Price: € 69,50

Closer to Vermeer explores the world of Johannes Vermeer, a painter whose work continues to fascinate more than 350 years after his death. Taking the landmark 2023 Rijksmuseum exhibition as a point of departure, this volume brings together new art-historical and technical research by leading international experts. How did Vermeer translate his creative ideas into paint? Did the seventeenth-century Dutch master truly rely on optical devices? What do the carefully rendered objects in his interiors reveal about the artist himself? And how has the perception of his small but extraordinary oeuvre evolved over time?

Using the latest imaging techniques, researchers scrutinize Vermeer’s masterpieces, yielding compelling new insights into his artistic process, material choices, and technical virtuosity. These investigations contribute to a deeper understanding of Vermeer’s painting technique throughout his career. Other specialists revisit seventeenth-century sources, uncover new archival documents, and explore Vermeer’s patrons and the material world he portrayed. The objects depicted in his interiors—maps, pearls, porcelain, kitchenware—are examined not merely as visual motifs, but as clues to his worldview and working methods.

At once scholarly and accessible, Closer to Vermeer offers a fresh, intimate perspective on one of the most enigmatic and beloved painters—a vital resource and enduring reference for specialists and art lovers alike.

Closer to Vermeer: New Research on the Painter and His Art

By literally opening the door, Vermeer makes the scene accessible to the viewer. These and the many other new discoveries in the book paint a picture of a dedicated artist constantly striving to perfect his paintings.

The research was conducted by scientists, conservators, and curators from institutions including the Rijksmuseum, the Mauritshuis in The Hague, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, The Frick Collection and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in London, and the University of Antwerp.

New insightsEarlier in this same study, it was discovered that in The Milkmaid, Vermeer had initially included a jug holder and a fire basket, but later painted them out. Using the latest research techniques, we now know that 30 of the 37 paintings attributed to Vermeer show changes, ranging from subtle corrections to radical alterations in composition and meaning. These findings offer new insights into Vermeer’s working methods, use of materials, and painting technique.

New archival discoveriesThanks to research by various art historians, new sources and archival documents have surfaced, offering fresh insights into Vermeer’s personal life, his patrons, and the objects he depicted.

Collaboration

The research was conducted by scientists, conservators, and curators from institutions including the Rijksmuseum, the Mauritshuis in The Hague, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, The Frick Collection and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in London, and the University of Antwerp.

:

- In Diana and her Nymphs (Mauritshuis, The Hague), Vermeer originally painted an ornate quiver with arrows lying on the rock to the left of the goddess Diana. This quiver bears striking similarities in design and colour to the one at Cupid’s feet in Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden), which Vermeer painted a few years later.

- The wide brim of the black hat worn by the officer in Officer and Laughing Girl (The Frick Collection, New York) was originally adorned by Vermeer with several lavish, colorful feathers.

- The open book — and even the exact page — in Allegory of the Faith (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) has now been identified as The Life of Hugo in Generale Legende der Heyligen met het leven Iesu Christi ende Marie by Pedro de Ribadeneira and Heribert Rosweyde (third edition, 1640).

- Research into Vermeer’s use of blue and green pigments shows that his application of these colours changed over the course of his career. This suggests revisiting the chronology of some of his works.

- A newly discovered document bearing Vermeer’s signature proves that he actively acted as a representative for his in-laws, the Thins-Bolnes family, managing their lands in Oud-Beijerland.

- Two newly discovered documents point to Maria de Knuijt, rather than to her husband, as Vermeer’s principal patron, who actively supported his work.

These and many other new discoveries and insights have been brought together in the book Closer to Vermeer: New Research on the Painter and His Art, which is available now.

Contents

- Taco Dibbits

"The Oeuvre of Johannes Vermeer - Note from the Editors

- Foreword

- Pieter Roelofs

Closer to Vermeer at the Rijksmuseum: The 2023 Retrospective Exhibition in Amsterdam - Anna Krekeler, Francesca Gabrieli, Annelies van Loon and Ige Verslype

Compositions in the Making: Vermeer’s Changes - Ige Verslype

Vermeer’s Canvases: Weave Maps and Matches in a Wider Perspective - Paul J.C. van Laar

Illuminating the Obscure: The Relationship between Vermeer’s Works and Seventeenth-Century Optical Developments - David G. Stork

Did Vermeer Use Optics? New Insights from Computer-Assisted Connoisseurship - Maria de Knuijt and Judith Noorman

Women’s Vermeers: Maria de Knuijt and New Archival Documentation on Vermeer’s Primary Patron - Helen Howard, Matteo Borri, Melchior Di Crescenzo, David Peggie, Rachel Billinge, Catherine Higgitt and Marika Spring

Young Woman Seated at a Virginal and Young Woman Standing at a Virginal: A New Technical Study of Two of Vermeer’s Late Masterpieces - Dorothy Mahon, Silvia A. Centeno and Federico Carò

A Maid Asleep and Study of a Young Woman: New Discoveries from Imaging and Chemical Analyses - Kathryn A. Dooley, John K. Delaney, E. Melanie Gifford, Dina Anchin, Lisha D. Glinsman, Alexandra Libby and Marjorie E. Wieseman

The Man Beneath Vermeer’s Girl with the Red Hat: Improved Visualization Using Chemical Imaging - Paul Taylor

Vermeer’s Art of Painting: Catharina Bolnes’s ‘Schilderconst’ and the Viennese Schilderkamer - Elke Oberthaler, Frederik Vrameert, Katharina Uhlir, Steven De Meyer and Koen Janssens

Tracing the Effects of Ageing in Johannes Vermeer’s The Art of Painting: A Closer Look at Palmette - Annelies van Loon, Francesca Gabrieli, Anna Krekeler, Ige Verslype and Frederik Vrameert

From Palette to Perfection: Vermeer’s Distinctive Use of Blue and Green Pigments - Frederik Vrameert, Maartje Stols-Witlox, Annelies van Loon and Koen Janssens

Vermeer’s White(s): Seventeenth-Century Methods Used to Manipulate the Working Properties of Lead White - Paolo D'Imporzano and Gareth R. Davies

Lead Isotope Studies of Vermeer’s Paintings: Myths and Realities - Aimee Ng

Vermeer’s Pearls: Considering the Place of Pearls in the Artist’s World and Imagination - Christian An

Object Matters: Vermeer, Material Culture and Adaptations of Asian Porcelain - Alexandra van Dongen

The Tangible World of Johannes Vermeer: Domestic Artefacts as Artists’ Props - Rozemarijn J.W. Landsman

The Highlights of Vermeer’s Maps - Evelyne Verheggen

Painted Devotion to Saints in Vermeer’s Allegory of the Catholic Faith - Esther van Duijn, Sabrina Meloni, Carol Pottasch and Ige Verslype

Retouching and Overpainting Vermeer: A Historical Perspective - Justine Rinnooy Kan, Daphne Martens, Quentin Buvelot and Ariane van Suchtelen

Vermeer in the Spotlight: The Exhibitions of 1935, 1966 and 1995–1996 - Abbie Vandivere

Who’s that Girl? Girl with a Pearl Earring in 1665, and her Current Appearance in 3D - Jonathan Janson

Essential Vermeer

Revisiting Vermeer’s Delft residence—A response to Hans Slager

"A Brief Reply to Hans Slager on the Issue of Vermeer's Residence" by Frans Grijzenhout

https://www.essentialvermeer.com/misc/finding-vermeer-reply-to-slager-final.html

In his new article, "A Brief Reply to Hans Slager on the Issue of Vermeer's Residence," Frans Grijzenhout responds to Hans Slager’s rejection of his earlier argument regarding the Delft residence of Johannes Vermeer and his family. Contrary to Slager’s claim that the family lived in the smaller Trapmolen house on the western corner of Oude Langendijk and Molenpoort, Grijzenhout maintains—based on primary documentation—that they resided in the more spacious Groot Serpent on the eastern corner. This conclusion draws heavily on the only known tax register to mention Maria Thins, Vermeer’s mother-in-law, and her neighbors, placing her among the wealthiest citizens of Delft in 1674.

Grijzenhout addresses Slager's doubts about the sequential nature of this register and demonstrates that his key objection—centered on the residency of one Jannetge Stevens—is unsupported by archival evidence. Detailed analysis of property transactions and estate inventories shows that Stevens did not own or occupy the relevant properties until well after 1674. The register’s structure thus remains reliable for establishing residential order, supporting my original claim.

While the precise location of Vermeer’s home might seem trivial compared to broader historical questions, it has important implications for understanding his social context and the domestic settings so central to his art. Grijzenhout concludes by reaffirming his earlier findings and briefly countering Slager’s reinterpretation of the location of the Jesuit church east of Molenpoort, a topic not directly related to Vermeer but touched upon in his critique.

Vermeer-related temporary exhibition in Marseille

Lire le ciel. Sous les étoiles en Méditerranée (Reading the Sky: Under the Stars in the Mediterranean)

July 9, 2025– January 5, 2026

Mucem in Marseille (Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur)

https://www.mucem.org/programme/exposition-et-temps-forts/lire-le-ciel

:

The exhibition Reading the Sky explores how the night sky has been perceived in the Mediterranean region, as seen from Earth. From the earliest records of the ancient Mesopotamian heavens to the popularity of contemporary astrology—passing through medieval Arab-Muslim astronomy and the Galilean revolution—Mediterranean societies have looked to the stars to understand their place in the cosmos and to organize life on Earth. Knowledge and belief circulated across the region, establishing a shared cultural understanding of the sky that still informs how we think about the stars today.

Among the 150 works on display will be Vermeer's masterwork, The Astronomer. It will be on display during the first three months of the exhibition, until October 7th, together with The Astronomer by Luca Giordano (from Musée de Chambéry).

1668

Oil on canvas

50 x 45 cm. (19 5/8 x 17 3/4 in.)

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Luca Giordano

1655

Oil on canvas, Musée de Chambéry, Chambéry

Through a dialogue between art and science, the exhibition seeks to question our present-day connection to the starry sky. Since Antiquity, observing the regularity of celestial bodies has allowed humans to structure daily life, such as navigating across land and sea or establishing calendars. Celestial phenomena were also seen as signs influencing everyday life: the phases of the Moon, the passage of comets, the movements of planets through constellations, and so on. This link between macrocosm and microcosm played a role in the governance of states and the interpretation of individual behavior, with astronomy and astrology long functioning in tandem.

Oil on panel

©Archivio di Stato, Siena, Italy, photo by Luca Betti

Although modern astronomy has challenged many of these beliefs, popular culture continues to maintain a deep connection with the stars, viewing the sky as a canvas for projecting fundamental human questions. Today, even as the stars are fading under urban light pollution, we still search for constellations, gaze at the beauty of the night sky, and reflect on our relationship with the environment.

Reading the Sky presents exceptional works of art and everyday objects that bear witness to this history, shown alongside contemporary artworks that respond to them. In keeping with the Mucem’s transdisciplinary approach, the exhibition blends archaeological, scientific, and ethnographic objects with works of art, manuscripts, and oral heritage. It includes more than one hundred works from Mucem’s own collection and benefits from over two hundred loans from national, regional, and international institutions.

:

Juliette Bessette, historienne de l’art, Université de Lausanne

Enguerrand Lascols, conservateur du patrimoine, Mucem

EV founder Jonathan Janson questions authenticity of Young Woman Seated at the Virginal (Leiden Collection)

"Young Woman Seated at a Virginal: A Second Look"

Jonathan Janson

https://www.essentialvermeer.com/misc/Young-Woman-Seated-at-a-Virginal-A-Second-Look.pdf

(attributed to Johannes Vermeer)

c. 1670

Oil on canvas, 25.2 x 20 cm.

Leiden Collection, New York

Since the 2004 sale of Young Woman Seated at a Virginal at Sotheby’s, this small canvas has been accepted as an authentic painting by Vermeer almost exclusively on the basis of a decade-long technical investigation spearheaded by Sotheby’s itself. Since then, there has been only a handful of high-intensity critical analyses of this "new Vermeer." In this essay, I attempt to evaluate the picture from a fresh point of view via a side-by-side comparison with Vermeer’s later works, such as The Lacemaker, The Guitar Player, Lady Standing at a Virginal, and Lady Seated at a Virginal. These paintings—whatever their expressive merit—rank among Vermeer's most technically refined and compositionally innovative achievements, and, by comparison, I believe, expose the rudimentary design and numerous technical shortcomings of the Leiden painting that have thus far been substantively unaddressed.

Special Vermeer exhibition at the newly reopened Frick Collection in 2025

Vermeer’s Love Letters

June 18 –September 8 , 2025

Frick Collection, New York

https://www.frick.org/exhibitions/vermeer_love_letters/video

The Frick Collection will reopen in April 2025 (exact date to be announced), introducing significant changes and additions to its renowned New York City mansion. Among the highlights of the reopening is a groundbreaking Vermeer exhibition, Vermeer’s Love Letters,which will bring together three notable Vermeer paintings with a letter-writing theme: Mistress and Maid (Frick Collection), The Love Letter (Rijksmuseum), and Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid (National Gallery of Ireland). This exhibition will run from June 18 to September 8, 2025, and will showcase Vermeer's intimate depictions of letter-writing within a specially-designed gallery, offering an unparalleled viewing experience, and will offer visitors an opportunity to consider Vermeer’s treatment of the theme of letters as well as his depiction of women of different social classes.

Related Events

-

Saturday, July 26, 2025

9:15 a.m. EDT – Gallery Conversation: "Vermeer’s Love Letters"

In-Person: The Frick Collection

Registration full -

Thursday, July 31, 2025

5:15 p.m. EDT – Gallery Conversation: "Vermeer’s Love Letters"

In-Person: The Frick Collection

Registration full -

Wednesday, August 6, 2025

6:00 p.m. EDT – Continue the Conversation: "Vermeer’s Love Letters"

Online: Zoom

Free with registration

The exhibition is curated by Dr. Robert Fucci, a distinguished expert on Vermeer from the University of Amsterdam, who will author a catalogue focused on the three works and their broader themes in seventeenth-century Dutch art.

In addition to the Vermeer exhibition, the museum’s extensive renovations include opening the second floor of the mansion to the public for the first time. This newly accessible space will feature ten galleries, including the Boucher Room in its original setting, along with displays of recently acquired objects, clocks, and watches. Visitors can also explore a new Cabinet Gallery on the first floor, which will exhibit rare drawings and sketches by artists such as Rubens, Degas, and Goya.

This reopening underscores the Frick's dedication to both its historic legacy and the enhancement of public access to its collections, aiming to captivate both new and returning visitors with its transformed and expanded spaces.

The Washington D. C: National Gallery of Art removes Vermeer's Girl with a Flute from display

Girl with a Flute, now attributed by the National Gallery of Art (NGA) to the "studio of Johannes Vermeer" rather than to the artist himself, is currently not on display. While the NGA has provided no future date for its return to view, the gallery explains that its temporary removal is due to the challenge of creating a balanced wall display and managing the limited space available to exhibit its collection.

In light of the NGA's reclassification, the decision not to display the painting may disadvantage both visitors and scholars who wish to evaluate and enjoy the painting, as it limits opportunities to engage with this debated work, especially considering that the work was for years hung next to Vermeer's Girl with a Red Hat and Woman Holding a Balance, and in close proximity to the Lady Writing. Displaying Girl with a Flute alongside the these Vermeer paintings would offer an invaluable chance for comparison and analysis, particularly given its historical inclusion in Vermeer's oeuvre. The reasoning behind the painting’s re-attribution is detailed in the online publication "Vermeer’s Studio and the Girl with a Flute: New Findings from the National Gallery of Art," Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 14:2 (Summer 2022), authored by Marjorie E. Wieseman, Alexandra Libby, E. Melanie Gifford, and Dina Anchin.

Following the NGA publication, the Rijksmuseum displayed Girl with a Flute as an authentic Vermeer in its 2023 Vermeer retrospective. Jonathan Janson, founder of Essential Vermeer, has released a YouTube video defending the painting's authenticity, critically analyzing the NGA's claims and presenting arguments in support of its attribution to Vermeer.

Vermeer-Related Exhibition: From Rembrandt to Vermeer, Masterpieces from The Leiden Collection

From Rembrandt to Vermeer, Masterpieces from The Leiden Collection

H’ART Museum, Amsterdam

April 9–August 24, 2025

https://www.hartmuseum.nl/en/exhibitions/rembrandt-to-vermeer/

To celebrate Amsterdam’s 750th anniversary, From Rembrandt to Vermeer showcases various aspects of daily city life in the 17th century. All seventy-five paintings on display come from The Leiden Collection, founded by Thomas S. Kaplan and Daphne Recanati Kaplan. Featuring no fewer than 18 Rembrandts and many other important Dutch pictures, the exhibition concludes with the Young Woman Seated at a Virginal, attributed to Vermeer.