The Guitar Player

(De gitaarspeelster)c. 1670–1673

Oil on canvas, 53 x 46.3 cm. (20 7/8 x 18 1/4 in.)

Kenwood House English Heritage as Trustees of the Iveagh Bequest, London

inv. 88028841

The textual material contained in the Essential Vermeer Interactive Catalogue would fill a hefty-sized book, and is enhanced by more than 1,000 corollary images. In order to use the catalogue most advantageously:

1. Scroll your mouse over the painting to a point of particular interest. Relative information and images will slide into the box located to the right of the painting. To fix and scroll the slide-in information, single click on area of interest. To release the slide-in information, single-click the "dismiss" buttton and continue exploring.

2. To access Special Topics and Fact Sheet information and accessory images, single-click any list item. To release slide-in information, click on any list item and continue exploring.

The landscape painting on the background wall

A Wooded Landscape with a Gentleman

and Dogs in the Foreground

Pieter Jansz van Asch

c. 1670

(whereabouts unknown)

The art historian Gregor Weber identified the picture-within-a-picture that hangs behind the guitarist's head as A Wooded Landscape with a Gentleman and Dogs in the Foreground by Pieter Jansz. van Asch. In Vermeer's version, Van Asch's composition has been cropped on the right and slightly on the top. The group of gentlemen and dogs is obscured by the musician's head.

Van Asch's landscape might have been in Vermeer's possession at the time of his death. Like many other Dutch artists, Vermeer traded in paintings of his colleagues to supplement his income, as most painters could not sustain themselves solely by painting. In his later years, Vermeer's business struggled. Catharina Bolnes, Vermeer's wife, mentioned in a petition to her creditors that her late husband "during the prolonged and devastating war with France had not only been unable to sell any of his pieces but also, much to his detriment, remained burdened with the paintings of others he was trading. Consequently, due to the immense responsibility of his children and lacking his own resources, he experienced such a decline and decay. This took such a toll on him that within a day or two, he transitioned from health to death."

Vermeer's struggles during the war with France mirror those of many artists during times of political and economic upheaval. Economic instability often forces artists to find alternative sources of income, as the market for luxury goods, such as art, diminishes. This reliance on alternative income can change the focus of an artist's work or reduce the time they can dedicate to their craft. In some cases, as with Vermeer, the stresses related to economic hardship can have severe personal consequences. His wife's testimony provides a poignant reflection on the toll that such challenges can take on an individual's mental and physical well-being.

The young girl

Perhaps more than in any other painting by Vermeer, there is a suggestion of motion in the Kenwood painting, as if we see a snapshot of a fleeting moment in time. According to scholar Elise Goodman, even though we lack details about Vermeer's literary and musical preferences, the young girl depicted in the current painting belongs to the haute bourgeoisie. She was likely multilingual, reading, writing and speaking in several tongues. It is probable that she amassed a collection of European poetry and had an appreciation for the lyrics found in Dutch, French and English songbooks, which were widely circulated in the Netherlands during the 17th century. The fashion in which her hair is styled, her attire and her guitar mirror the prevailing trends of her time.

Contrary to most of Vermeer's subjects, who express emotions in a subdued manner, the young girl's forthright demeanor stands out. Her playful expression might imply the proximity of a male observer. Technically speaking, her facial features are portrayed with such simplicity that discerning any potential resemblance to other figures in Vermeer's paintings becomes a challenging task.

The significance of the guitar in Vermeer's painting could be manifold. In the 17th century, guitars were often symbolic of love or romance, especially in Dutch genre painting. Their inclusion could point to courtship or romantic intention. Furthermore, the international spread of the guitar as a favored instrument in Europe had made it a signifier of cultural sophistication and worldly knowledge, which aligns well with the portrait's depiction of a multilingual, well-read young woman.

The pearl necklace

In the 17th century, pearls symbolized significant status. English diarist Samuel Pepys, in 1660, purchased a pearl necklace for 4 1/2 pounds, and in 1666, he acquired another for 80 pounds. These amounts equated to roughly 45 and 800 guilders, respectively. Around the same period, French art connoisseur Balthasar de Monconys viewed a single-figure painting by Vermeer, priced at 600 guilders, a sum he deemed exorbitant.

Though the somewhat uniform subject matter of Vermeer's limited oeuvre may imply a static artistic development over his two-decade career, a more detailed examination uncovers his persistent experimentation with innovative approaches to illuminate textures and space.

In the present work, Vermeer devised an ingeniously minimalistic method to depict the pearl necklace, a technique he subsequently employed in the Allegory of Faith. He first set down the colors of the girl's neck, over which he layered a continuous light greenish-gray paint strip, forming the elliptical base for the pearl strand. At this point, he made no efforts to delineate the individual pearls' shapes; rather, their edges were intentionally kept indistinct to capture their inherent translucency. Once the foundational gray paint layer had sufficiently dried, Vermeer skillfully placed a series of dense white spherical highlights, suggesting the pearls' location, roundness and unique reflective attributes.

The modeling

This detail underscores the clear shift toward stylization in Vermeer's later pieces. Rather than presenting a continuously modeled form, objects are transformed into a sequence of flat, variably toned paint patches. Yet, these patches astoundingly capture the play of light on the delicately drawn fingers of the young girl.

Vermeer's transition to a more stylized approach in his later pieces can be viewed as an evolution of his artistic voice. As artists mature, they often distill their techniques, moving away from intricate details toward a more abstracted, even symbolic, representation. This development can arise from a variety of influences, ranging from personal introspection to broader shifts in the artistic milieu of the time or economic necessities. In Vermeer's case, this stylization not only demonstrates a mastery of technique but also an understanding of how to convey complex visuals and perceptual sensations with greater simplicity.

The guitar

The guitar was emerging as a fashionable instrument in the 17th century, popular for solo accompaniment. The music it produced had a robustness surpassing that of the lute, largely because its chords resonated in ways the lute couldn't achieve. By this time, the lute was increasingly associated with a bygone, refined era in which music was revered for its sonic purity. As Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. noted, the vivid and forthright nature of The Guitar Player was more indicative of the contemporary musical world represented by the guitar than of the lute's reserved and reflective traditions.

The representation of the guitar is a masterstroke of technique. Utmost care was taken in portraying the decorative black and white inlay of its border. This visually punctuated effect amplifies the vibrancy of the painting and introduces a rhythm in line with the musical theme. The intricate hand-carved sound hole is depicted with bold impasto strokes, capturing brilliantly how light skims across its glossy, uneven surface. Yet, the most refined method was employed for the instrument's strings. Upon close examination, some appear slightly out of focus, suggesting vibration—a technique rarely seen in 17th-century art.

Baroque Guitar

Rene Voboam

1664

Pine or spruce, mother-of-pearl, ivory and ebony 93.7 cm. (overall length)

Ashmolean Museum, OxfordInterior with a Merry Company

Joost Cornelisz. Droochsloot

1645

Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 127.9 cm.

Centraal Museum, Utrecht

The reason behind Vermeer's marked simplification of his approach remains a topic of debate. Some art historians posit that his creative vigor diminished due to economic hardships or personal tragedies. Some think he was aligning with the prevailing French influence that was shaping high culture. Others speculate that he aimed to expedite the painting process to remain competitive in a volatile art market, which was deeply affected by the French invasion of the Netherlands in 1672.

The guitar's popularity in the 17th century can be linked to broader shifts in European society. With urbanization and a growing middle class, there was an increase in leisure time and disposable income. Music became more accessible to ordinary people, not just the elite. Instruments like the guitar, which were versatile and relatively easy to learn, became popular in households. Furthermore, the guitar's association with the emerging Baroque style, which emphasized emotion and individual expression, made it a fitting symbol of the times.

Satin

Paternal Admonition (detail)

Gerrit ter Borch

1654–1655

Oil on canvas, 71 x73 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Although satin and silk are both prized for their sheen and smoothness, they are distinct. Silk refers to a specific material derived from silkworm cocoons, which are spun into threads and subsequently woven. Satin, in contrast, is a weave that creates a fabric with one side matte and the other glossy. It can be made from a variety of materials, including silk. Both materials trace their origins to China. Silk's development dates back to as early as 6000 B.C., whereas satin emerged in the Middle Ages. The term "satin" is derived from the Chinese port of Zaitun (Quanzhou) in Fujian province, where Arab traders procured the fabric.

There were instances when satin was starched and ironed to give it rigidity. Given its dense drape, the dress in The Guitar Player seems to be fashioned from starched satin.

Seventeenth-century Dutch artists reveled in capturing the interplay of light on various textures. Rendering opulent fabrics such as silk, satin and velvet was viewed as a benchmark of a painter's skill, and the elite artists consistently seized opportunities to demonstrate their expertise in this domain. In 1642, Philip Angel remarked, "A commendable painter should be adept at vividly capturing these contrasts with his strokes, differentiating between coarse, textured fabrics and the uniform smoothness of satin..."

Depicting satin dresses with precision was a major selling point in the competitive art arena. Artists like Pieter Codde and Willem Duyster excelled in this aspect, but Gerrit ter Borch stood out as the most accomplished. Therefore, when Vermeer incorporated such an exquisite garment in his painting, he recognized that it would be held up against the works of one of the most revered and in-demand artists of his era.

Illustrating lavish fabrics posed significant challenges and demanded extra hours. The complexity of illustrating satin and other fine fabrics is not just about rendering their texture, but also capturing the reflection and refraction of light. The interplay of light on satin, for instance, is unique due to its smooth, glossy surface. This challenge is compounded when artists attempt to depict the fabric in motion or as it drapes over a form. A skilled artist can convey not just the material's texture, but also its weight, volume and the subtleties of how it interacts with light. Given that the folds altered with the sitter's movements and couldn't typically be completed in one session, artists resorted to dressing life-sized wooden mannequins in the sitter's most expensive attire.

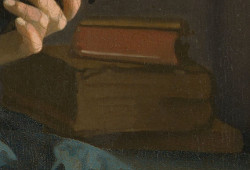

The three books on the table

The three books on the table lend an aura of sophistication to the image, even though their specific subjects or titles remain unknown. Some critics argue that the considerable size of the central volume suggests it may be a Bible. One critic speculated that if the sacred text is present in such a worldly setting, it might serve as a subtle rebuke to the girl's frivolous pursuits. If this interpretation holds, it's clear that the enchanting musician appears to disregard any moral counsel the artist might have intended.

Walter Liedtke, on the other hand, suggested that the three books "denote learning, an emerging yet familiar theme in Dutch paintings of stylish young women."

The environment

Discerning the exact spatial context in which the young girl resides is challenging. However, she seems to be positioned significantly away from the background wall, even if the golden frame appears to bind her closely to it. The concealed window on the far right bears resemblance to windows seen in other interiors by Vermeer, featuring two lower and two upper casements. The upper casements had shutters that could be closed from within, while the lower shutters were situated on the home's exterior. The curtain in this composition likely served to moderate the incoming light and, potentially, to shield against prying eyes. The illumination on the girl probably emanates from another window, closer to the vantage point of the artist.

The tip of the lion-head finial chair

The Duet (detail)

Jan Miense Molenaer

c. 1635–1636

Oil on panel, 42.2 x 51.4 cm.

Private collection (?)

Though faintly discernible, a dark silhouette depicts the top of a lion-head finial from the so-called Spanish chair, a motif recurrent in Vermeer's oeuvre. These chairs likely derived their name from the prevalent use of leather in Spain, as opposed to cloth. Such chairs were so esteemed that their craftsmen viewed themselves as a distinguished subset within the artisan guilds. Comparable chairs frequently appear in genre interiors of Vermeer's era. A clear example of this chair is visible in The Duet by Jan Miense Molenaer.

The elegant yellow morning jacket

A similarly elegant fur-trimmed yellow morning jacket is featured in five other paintings by Vermeer, including "Mistress and Maid." Such a garment is also listed among the belongings of his cherished wife, Catharina. The way the jacket's folds are depicted varies so much from one painting to another that it seems to be made from different fabrics. However, a comparison of the shapes and distribution of spots on the fur trim in three of the paintings ("A Lady Writing," "Woman with a Pearl Necklace," and "Mistress and Maid") confirms it's the same item. From the mid-1660s onward, these jackets appeared frequently in Dutch genre interiors and were presented in a myriad of colors. Unfortunately, very few jackets from the 17th century remain today.

In this painting, the jacket's luminescent material is abstracted into a pattern that appears almost disjointed from the actual folds and tucks of the garment. The fur trim, once depicted with utmost precision, has been transformed into peculiarly shaped patches of thin gray paint. The reasons behind Vermeer's shift from a detailed portrayal of visual experience to such a pronounced stylized approach remain a topic of debate.

Costume historians inform us that the spotted fur trim on Vermeer's jackets was likely not the coveted ermine but rather fur from cats, squirrels, or mice adorned with artificial spots. Notably, even in the inventories of the most affluent women, there is no mention of ermine.

The white-washed wall

A component of Vermeer's motifs, often overlooked but essential, is the white-washed wall. These understated walls form the backdrop for the artist's subdued dramas, serving multiple pictorial purposes. They not only define the spatial depth of the painting but also establish the lighting scheme and mood with remarkable precision. Moreover, as "negative spaces," they frequently play a pivotal role in achieving compositional balance. In no other Dutch interior painter's work do the walls command such a pronounced presence, their plain surfaces meticulously explored.

Interior with a Merry Company

Joost Cornelisz. Droochsloot

1645

Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 127.9 cm.

Centraal Museum, Utrecht

Vermeer utilized various pictorial strategies to convey each wall's distinct illusionistic qualities and to imply the translucence of cast shadows. The precise hue of the wall determines the temperature of the incoming light, while chiaroscuro values and brushwork indicate the light's direction, intensity and surface texture. Interestingly, the pigment combinations that Vermeer and other Dutch interior painters typically used were limited, primarily consisting of lead white, black and raw umber—a reliable yet unremarkable brown. The significance Vermeer placed on depicting their luminosity is supported by well-documented evidence that he intentionally incorporated minute amounts of natural ultramarine into some of his walls, even if sometimes it's detected only subconsciously. This was the most costly pigment utilized by painters across Europe.

Delft building historian Wim Weeve notes that since the Middle Ages, bare white walls have been a common feature in the interiors of Dutch homes, castles and churches. However, these walls weren't merely "white-washed" with a brush. They were first coated with a thicker layer of lime putty, which, in Holland—where Vermeer resided and produced his works—was derived from calcinated seashells. After applying the putty layer, the walls underwent repeated white-washing as they accumulated dirt. Sometimes, these walls were partially adorned with hand-painted designs, but by the 17th century, such decorations had fallen out of favor with the elite. Walls could be white-washed repeatedly to regain their immaculate appearance. Only industrial structures or warehouses retained bare brick walls.

special topics

- Vermeer's fingerprint?

- The Guitar Player under candlelight

- Paul McCartney and The Guitar Player

- Female beauty and nature

- The young girl

- The French gilt frame

- Vermeer's final years: poverty and sadness

- A very unusual lighting scheme

- Masters of satin

- A daring composition

- A rare canvas

- An alternative "painting-within-a-painting"

- Did Vermeer make an exact copy of the Guitar Player?

- Listen to period guitar music

The signature

Signed right on the lower side of the curtain

(Click here to access a complete study of Vermeer's signatures.)

Dates

1671–1672

Albert Blankert, Vermeer: 1632–1675, 1975

c. 1670

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer, London, 2000

c. 1670–1672

Walter Liedtke, Vermeer: The Complete Paintings, New York, 2008

c. 1672–1673

(Click here to access a complete study of the dates of Vermeer's paintings).

Provenance

- ?) Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven, Delft (d. 1674)

- (?) his widow, Maria de Knuijt, Delft (d. 1681)

- (?) their daughter, Magdalena van Ruijven, Delft (d. 1682)

- (?) her widower, Jacob Abrahamsz Dissius (d. 1695)

- Dissius sale, Amsterdam, 16 May, 1696, no. 4

- ?Jan Danser Nijman, Amsterdam (before 1794)

- Henry Temple, 2nd Viscount Palmerston, London (1794-d.1802)

- his son, Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, London and Broadlands, Hampshire (1802-d.1865)

- his stepson, William Francis Cowper-Temple, 1st Baron Mount Temple, Broadlands, Hampshire (1865-d.1888)

- his nephew, (Anthony) Evelyn Melbourne Ashley (in 1888, sold to Agnew)

- [Agnew, London, 1888–1889, sold to Guinness]

- Edward Cecil Guinness, (from 1919) Earl of Iveagh, London (1889-d.1927)

- The Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood House, London (inv. 88028841)

Exhibitions

- London 1871

An Exhibition of the Old Masters, Associated with Works of Deceased Masters of the British School

Royal Academy

no. 266, as "A Lady Playing a Guitar,” lent by the Rt. Hon. W. Cowper-Temple - London 1892

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters and by Deceased Masters of the British School including a Collection of Watercolour Drawings, Studies and Sketches from Nature

Royal Academy

no. 46, as "The Lute Player," lent by Lord Iveagh - London November–December, 1922

Old Masters

Agnew & Sons Ltd, London

no. 33 - London January 12–March, 1928

Exhibition of Works by Late Members of the Royal Academy and of the Iveagh Bequest of Works by Old Masters (Kenwood collection)

Royal Academy, London

no. 216 - Manchester April 2–June 2, 1928

Exhibition of Old Masters Presented to the Nation by the Late Earl of Iveagh

Manchester City Art Gallery - The Hague June 25–September 5, 1966

In het licht van Vermeer

Mauritshuis

no. VIII. - London July, 2012–2013

"The Guitar Player"

National Gallery - London June 26–September 8, 2013

Vermeer and Music: Love and Leisure in the Dutch Golden Age

National Gallery

68, no. 24 and ill. - London September 1, 2025–January 11, 2026

Double Vision: Vermeer at Kenwood

Kenwood House, Hampstead

(Click here to access a complete, sortable list of the exhibitions of Vermeer's paintings).

Female beauty & nature

Lady with a Lute

Palma Vecchio

Oil on canvas, 96.5 x 73.7 cm.

Alnwick Cle, Alnwick

According to art historian Elise Goodman, Vermeer's The Guitar Player a construct commonly referred to as the "lady and the landscape." This convention, popular in 17th-century painting, prints and literature, served as a means to celebrate female beauty. Palma Vecchio's Lady with a Lute is a quintessential representation of this trend, depicting a female musician against the backdrop of a picturesque landscape.

Goodman notes that the notion of a woman as a "masterpiece of nature," an object to be admired, owned and showcased, is a recurrent theme in the literary and artistic expressions of the 17th century. In various poetic works, the woman's features are artfully juxtaposed with elements of the natural world. The depiction of women as metaphorical trees or lush meadows was a prominent theme in English and French literature of the time. This motif also resonated in Dutch poetry, with notable works by Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft, Constantijn Huygens and Joost van den Vondel. In The Guitar Player, Vermeer may have drawn inspiration from this convention, subtly echoing the flowing curls of the girl's hair in the cascading branches of the serene landscape behind her—a connection initially highlighted by Lawrence Gowing.

Given that Vermeer was once sought after for his expertise on Italian art, it is likely he was acquainted with this style of representation. Italian artworks and prints, which frequently portrayed similar motifs, were widely disseminated across Europe and had a significant presence in the Dutch art market.

The young girl

John Michael Montias, Vermeer's principal biographer, mused that the yellow-jacketed girl exhibits the characteristic jaw formation of the Study of a Young Woman. If the date typically assigned to the picture (c. 1671–1672) is accurate, the image could represent Maria, Vermeer's eldest daughter, at seventeen or eighteen years old. Elisabeth, born around 1657, is a less likely subject as she was probably under fifteen when the Kenwood picture was painted.

Regardless, it's challenging to fathom how the father of eleven children could overlook their presence as he worked. Several critics have remarked on the clear divergence between the artist's immaculately ordered interiors and what might have been his chaotic daily life filled with numerous offspring. One wonders where the cradles, beds and chairs, listed in the inventory of movable goods after his passing, were scattered around the residence. Unlike many Dutch genre painters like Jan Steen, Nicolaes Maes and Gabriel Metsu who frequently included children in their compositions, Vermeer assigned them only two subtle yet poetic roles: in the Little Street and in the foreground of the View of Delft.

However, this peculiarity is not overly perplexing. Plainly stated, Vermeer's paintings weren't crafted as biographical statements. While they capture the zeitgeist and styles of his era, they weren't designed to reflect the conditions of his private life. As Walter Liedtke noted, Vermeer portrayed an elevated ideal. Issues like poverty, disease, the loss of loved ones and significant disasters that sometimes struck Delft are conspicuously absent in his subjects. Instead, they remain engrossed in beauty, the arts and sciences, spiritual pursuits and tempered worldly enjoyments.

Vermeer's final years: poverty & sadness

The exuberance evident in The Guitar Player is puzzling given the backdrop of Vermeer's personal life. During the period this painting was created, the artist grappled with severe financial strains, intensified by his expanding family. This strain was further compounded by an economic downturn and the near disappearance of the art market in the United Provinces due to the French invasion in 1672.

The unique compositional approach and condensed technique of The Guitar Player may have stemmed from a patron's request or Vermeer's endeavors to rise above his personal adversities. Regardless, it stands as perhaps his most joyous piece. Vermeer and his wife, Catharina Bolnes, evidently held this painting in high esteem, as it remained with Catharina after Vermeer's premature death in 1675. Later, she had to use it as collateral to settle a significant debt accrued with the Delft baker, Hendrick van Buyten. By 1675, Vermeer's unexpected demise left Catharina with eleven children, with ten still underage.

The French invasion of the Dutch Republic in 1672, known as the Rampjaar or "Disaster Year," had a profound impact on the socio-economic and political structures of the time. This event saw the Dutch Republic, one of the major European powers, face invasions not just from France, but also England, Münster and Cologne. The combined pressure led to significant political upheaval, economic downturns and, as mentioned, it all but wiped out the art market. The strain of these events on individuals, especially artists like Vermeer who depended on the patronage of the affluent classes, was palpable.

A very unusual lighting scheme

For reasons yet to be determined, the light in this painting enters from the right-hand side, deviating from the usual pictorial convention of light entering from the left. This tradition might be rooted in the practice where artists position their light source to the left, preventing the shadow cast by their working hand from obscuring the area they're painting. Additionally, the left-to-right reading direction of Western viewers further reinforces this formula's effectiveness.

Jørgen Wadum, a conservator and expert on Vermeer, has proposed that the infrequent instances where Vermeer's light enters from the right might be tailored to a collector's specific gallery, considering the natural light dynamics of the room. Could it be that Pieter van Ruijven, Vermeer's patron, had this intention when acquiring paintings from his preferred artist? This approach is reminiscent of artist Jacob van Campen, who under the guidance of Constantijn Huygens, conceived the Oranjezaal outside The Hague. For this particular space, it was specified that in certain paintings light should originate from the left and in others, contrarily, from the right. Such a decision aimed to enhance the illusion for viewers, ensuring that natural and painted light seemed to adhere to the same laws of nature.

he choice of light direction in paintings can indeed have profound implications on how a scene is perceived and understood by viewers. Light direction not only impacts the mood and atmosphere of a painting but also the perception of volume and depth. Painters often manipulate light based on the intended mood, the narrative of the piece, or the specific requirements of a commission. As suggested, if a painting was destined for a particular room with specific lighting conditions, it would make sense for the artist to consider the natural light source when choosing the direction of light within the painting.

A daring composition

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., an expert on Vermeer, has highlighted the unconventional nature of this composition. The girl is positioned significantly to the left, to the extent that her arm is cut off by the painting's left-hand edge. As viewers typically approach the painting from the right, they are met head-on with the guitar player's figure, making it challenging to direct attention to the other aspects of the painting, including the gold-framed landscape. This leaves a significant portion of the composition feeling starkly vacant. However, regardless of its idiosyncratic layout, it's near impossible for viewers to divert their attention from the captivating allure of the expertly rendered face, jacket, guitar and gown.

The structure, though distinct, is not devoid of compositional finesse. Vermeer astutely aligned the gilt frame and the vertically oriented tree with the center of the girl's body and the guitar's soundhole. This creates a vertical axis that offers a sense of stability to what might otherwise feel like a lopsided composition (refer to the diagram above).

A rare canvas

The practice of canvas relining is typically required for paintings every few generations due to the weakening of linen fibers. However, The Guitar Player stands out as an anomaly in 17th-century art as it has not undergone relining and remains affixed to its original strainer. As a result, the painting retains a freshness and luminosity that can sometimes be diminished when canvases are relined through the application of intense heat and heavy irons. This exceptional preservation can occasionally cause art historians to view the painting with a sense of unease. Notably, the canvas remains attached to the strainer using wooden pegs, a more economical choice compared to the metal nails of that era, which were laboriously crafted by hand on an individual basis.

Wooden pegs, also known as dowels or trenails, were used before the widespread availability of metal nails to secure canvas to the stretcher or strainer bars, especially during the Renaissance and the Baroque periods.

An alternative "painting-within-a-painting"

Riverscape with Travelers

Herman van Swanevelt

1644

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Grenoblex-Arts,

Grenoble

Although art historian Gregor Weber has identified the gilt-framed landscape as A Wooded Landscape with a Gentleman and Dogs in the Foreground by Pieter Jansz van Asch—Vermeer possibly owned this pictures, or it may have been part of his stock as an art dealer—, Bert Meijer recently noted strong affinities with a wooded landscape by Herman van Swanevelt.

Various authors, including Weber and Lisa Goodman, have attempted to assign specific symbolic meanings to the pictures-within-pictures that hang on the background walls of Vermeer's interior scenes, including the landscapes and seascapes. However, Bart Cornelks has recently argued that "They were no doubt included as generic landscapes, and indeed it took over three centuries to recognize them as works that can be linked to specific artists. Vermeer has taken considerable liberty with his examples to suit his needs, a fact that those who think of Vermeer’s paintings as entirely true-to-life should do well to remember. They are perfect exemplars of the fact that however closely Vermeer observed the motifs he included in his paintings, ultimately his pictures are products of an artistic vision rather than a faithful reproduction of the visible world. As for the question whether one can attach a specific meaning to these landscapes in the context of these paintings, the jury is out, although there can be little doubt that their idyllic nature strikes a congruous chord in the harmonious world of love that Vermeer evokes in these brilliantly conceived works."

Listen to period music

![]() Villanesque [2.14 MB], Guillaume Morlaye

Villanesque [2.14 MB], Guillaume Morlaye

performed by Michael Craddock

on a Renaissance guitar.

Baroque 5-course-guitar

attributed to Matteo Sellas, Venice, c. 1630–1650

Richly decorated with ivory, bone and various woods

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

There are various theories concerning the origin of the guitar. Some scholars posit that it is a distant descendant of the ancient Greek kithara, a notion that the etymological relationship between kithara and guitar might support. Others opine that its roots lie in the long-necked lutes of Mesopotamia. Between the 1st and 4th centuries A.D., certain short-necked lutes bearing guitar-like shapes were discovered in Central Asia.

In the early Middle Ages, the Arabs, often referred to as Moors, might have introduced instruments that carried the fundamental features of the guitar to Western Europe during their travels through Egypt en route to North Africa and Spain. This possibly gave rise to the term "Guitarra Morisca", which described a kind of guitar with a long neck, an oval soundbox and multiple sound holes on its soundboard. Depictions of such instruments can be found in medieval miniatures. Alongside them, one can also see the "Guitarra Latina," characterized by its unique curved sides. This design evolved into the contemporary guitar form familiar to us.

By the 15th century, the four-course guitar made its appearance. However, the number of courses (pairs of strings) became increasingly diverse over time. The four-course variant maintained its popularity among the general populace during the 17th and 18th centuries, primarily because its limited course range made it apt for lighter dance tunes and basic chord accompaniments for well-liked songs.

The 16th century witnessed the birth of the five-course guitar, initially in Italy. It emerged as a progression from the four-course version, offering a brighter, higher pitch range. The instrument proved versatile, suitable for both vocal accompaniments and continuo ensembles. This five-course variant saw a rise in popularity across Europe throughout the 17th century. Size-wise, both the four- and five-course guitars were considerably more compact than the Classical guitar of today.

A marked transformation in the guitar's nature was evident around the mid-18th century, mirroring shifts in prevailing musical styles. A style mirroring that of keyboard instruments, particularly the harpsichord, demanded authentic bass notes, emphasizing the addition of a bourdon on the fifth course. Gradually, the guitar began exhibiting characteristics and playing methods resonant with today's version.

Typically, the back of the guitar is flat, with whole gut frets wrapped around the neck. Its bridge bears a resemblance to the lute's, anchored on the body and flanked by "moustache"-like designs. The strings were generally crafted from gut. Between the 15th and 18th centuries, the soundhole donned a decorative rose design, which eventually gave way to an open style similar to contemporary guitars.

Two dominant techniques governed the playing style. One, known as "punteado" in Spain (or "pizzicato" in Italian), involved plucking individual strings. Another, the "rasgueado" (in Italian, either "battuto" or "battente"), entailed sweeping the hand across all strings, producing a distinct character for a piece.

An alternative "painting-within-a-painting"

Soldiers Fighting over Booty in a Barn (detail)

Willem Duyster

c. 1623–1624

Oil on oak, 37.6 x 57 cm.

National Gallery, London

Prior to the 1650s, upper-class Dutch women were depicted with sober chastity. However, courtly conventions began to gain traction among the Dutch bourgeoisie, contrasting their previously austere black attire and rigid lace collars. This thriving burgher class, having experienced severe wars and economic downturns, increasingly embraced the luxurious, aristocratic tastes in architecture, interior decor, fashion and art. By 1673, the English statesman and essayist Sir William Temple observed, "The old severe and frugal way of living is now almost out of date in Holland."

Depicting materials accurately has always challenged painters since the Renaissance. The uniform black attire of the bourgeoisie was no simple task to depict, given the complexities of modeling black pigment. Leonardo da Vinci advised drawing draperies "from the actual object", and Philip Angels, a contemporary of Vermeer, believed a proficient painter should distinctively portray silk, velvet, wool and linen.

The heightened luminosity of materials like silk and satin presented painters with a distinct set of challenges. These materials, unlike the opaque textures of wool, linen, or cotton, reflect more light, resulting in stark contrasts between lit and shadowed areas. The relative rigidity of satin, in particular, results in mirror-like facets that capture the hues of surrounding objects. When depicted skillfully, these fabrics mesmerize even the most discerning observer.

Of the Dutch artists who attempted to capture the essence of silk and satin, Willem Duyster was notably adept. Yet, only a few years later, Gerrit ter Borch's mastery eclipsed Duyster's, making the efforts of his contemporaries seem almost elementary. Ter Borch's exceptional skill in conveying not just the visual allure but the tangible quality of satin garnered him immense acclaim in the Netherlands. With the help of his gifted apprentices, Ter Borch created multiple renditions of his most celebrated compositions. In some instances, the exact satin gown was replicated to the detail. To meet the growing demand for his pieces, his workshop developed a method to mechanically replicate the sketches of his most renowned satin gowns.

Art historian Robert Baldwin opined that Ter Borch's silk dresses served as a decorous stand-in for the soft bodies concealed beneath, amplifying yet restraining male desire. He wrote, "Ter Borch's paintings of beautiful maidens in silk dresses constructed a rhetorical female beauty, intensifying the tension between desire and decorum." This newfound portrayal of female beauty introduced a hitherto forbidden courtly sensuality, making it even more enticing without compromising burgher decorum.

Originating in China, satin was initially produced from silk. By the 12th century, it was exported to Italy, and by the 14th century, satin garments, with their characteristic sheen, were highly coveted across Europe, often being the fabric of choice among the royalty. The term "satin" is derived from Zaitun (present-day Quanzhou) in Fujian province, the Chinese port where Middle-Eastern merchants procured it.

While traditional satin has a lustrous front and a matte reverse, modern versions are manufactured using polyester, acetate, nylon and rayon. Satin's unique shine is achieved through its weaving process, where some yarns are "floated" on the surface to reflect light, adding gloss. Occasionally, satin was starched and ironed to add volume, producing angular creases reminiscent of those seen in Vermeer's Guitar Player.

The French gilt frame

In his later years, Vermeer's painting technique took a sharp turn from naturalism to a more pronounced abstraction.

French, Louis XIII, carved and gilded frame with guilloche sight moulding and imbricated laurel leaf and berry ornament with flower heads at the centres

Dimensions: 33.7 x 26.8cm

Upon detailed examination, the intricate carvings of the French gilt are distilled and artfully reimagined into a sequence of simplified yet rhythmic brush strokes. This lively brushwork subtly suggests the frame's form and texture, rather than delineating it literally. Such vibrant application might have been designed to evoke the lively resonance of the guitar, while simultaneously casting a dazzling play of light reflecting off the lustrous gold.

In the current painting, as observed in The Love Letter and The Lacemaker from the same period, contours have evolved. They are no longer varied as they were in his earlier works, but consistently sharp. This variation in contours was once advocated to naturally depict a sense of roundness. Karel van Mander, author of Den Grondt der edel vry schilder-const, advised painters to maintain a distance between the lightest and darkest shades from the contours. This, he believed, would prevent the image from appearing two-dimensional and recommended edges that merge with the background, effectively enhancing the sense of depth.

Moreover, Vermeer limited the use of pronounced lines along the edges of contours in his works. Willem Goeree, the Dutch artist and art writer, observed, "in natural life, there are no lines, only an end or a certain cessation of the breadth and length of all tangible things that seem to expand or press against each other...thus, where color ends, it defines the form, devoid of lines." While lines can differentiate two colors of the same tonal value, using them to mark the boundary of forms can detract from the perception of depth, a central aspect of Dutch painting.

During an annual inspection by the conservators at Kenwood House, the painting was placed on a large table. A powerful light was shone onto the canvas from a sharp raking angle to identify any anomalies. This illumination revealed two fingerprints embedded in the light gray paint along the upper edge of the canvas. These marks had previously been overlooked. The fingerprints could belong to the artist or possibly someone from his household who handled the painting before it had adequately dried.

Another fingerprint was detected during the restoration of Vermeer's Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window.

Paul McCartney and The Guitar Player

In 2007, it was rumored that Paul McCartney, one of the preeminent musicians of the 20th century, frequented Kenwood House near one of his homes to admire Vermeer's Guitar Player. At times, he reportedly spent up to 40 minutes contemplating the painting. While some newspapers at the time hypothesized that McCartney sought solace from an ongoing divorce, one might find a simpler connection between McCartney and Vermeer by considering the uplifting spirit of Vermeer's work and McCartney's buoyant yet expressive bass guitar techniques evident in songs like Penny Lane and other small-scale musical masterpieces in the rock-and-roll genre. Notably, one of McCartney's songs shares the title Mistress and Maid with Vermeer's piece in the Frick Collection, although it's uncertain if the song title is a nod to Vermeer's art. Beyond music, the former Beatle has been linked to the art world, having taken up painting in the early 1980s.

Did Vermeer make a copy of The Guitar Player?

Lady with a Guitar

Johannes Vermeer (?)

1670s

Oil on canvas, 52.5 × 45.6 cm.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

An unknown Vermeer painting might be in the storeroom of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Although there are currently 35(?) acknowledged Vermeer works, Arie Wallert, an ex-Rijksmuseum conservation specialist, thinks there's an additional one. He posits that two versions of a painting depicting a young woman with a guitar exist; one at Kenwood House, London and another at the Philadelphia Museum. The latter was originally believed to be the original until the Kenwood version emerged in 1927. The Kenwood painting was in better condition, leading to its acceptance as the genuine version. Wallert, after analyzing Philadelphia's Lady with a Guitar, believes it's a genuine 17th-century Vermeer, based on the pigments used. Both paintings are similar in size and composition, derived from a now-lost sketch. However, the depicted hairstyles differ, leading to questions. Philadelphia's version is in poor condition due to over-cleaning. The painting's authenticity is further in question after claims that Vermeer had a studio, challenging long-held beliefs about his solitary work. The Philadelphia museum plans to promote further discussions about this mysterious painting.

d The Guitar Player in candlelight

During the installation of a new LED lighting system at Kenwood House, a remarkable discovery unfolded. The process led to the revelation of previously unnoticed intricacies within Vermeer's The Guitar Player.

As part of the transition to the new lighting, the painting was delicately taken out from its protective glass enclosure that had safeguarded it for over a century and a half. Subsequently, the artwork underwent examination by the soft glow of candlelight, mirroring the conditions under which Vermeer's original audience would have appreciated it. This unique perspective unveiled a series of visual enchantments created through adept manipulation of light and shadow by the artist. Particularly captivating was the pearlescent translucence encircling the subject's neck, which took on a tangible three-dimensional quality under the flickering candlelight. Intriguingly, nestled in a corner, a fingerprint, presumably belonging to the artist himself, was unveiled.

The act of scrutinizing the painting by candlelight granted the curators a privileged view into Vermeer's artistic techniques – revealing the intricate layers of paint, a rich palette of colors, diverse textures and an illusion of depth masterfully orchestrated by the artist. This technique imbued the artwork with a sense of three-dimensionality that resonated with its 17th-century audience. The newly introduced LED lighting system not only enhances the viewing experience for visitors but also serves as a safeguard for the entire collection, housing remarkable works by painting masters such as like Joshua Reynolds and Rembrandt.