The lives of seventeenth-century Dutch painters, and certainly Vermeer's, were deeply affected by the Guild of Saint Luke. This professional trade organization of artists and artisans regulated the commerce and production of potters, engravers, glass makers, tapestry weavers, faiencers, booksellers, sculptors, and painters alike. Each city had its own self-governing guild which protected and promoted local production. The following outline briefly describes the essential characteristics of the guild structure as well as Vermeer's association with the Guild of Saint Luke of Delft.

The drawing by Gerrit Lamberts (1776–1850) (fig. 1) represents the facade of the newly constructed Guild of Saint Luke in Delft on the Voldersgracht.

Purpose

In Delft, as in every other artistic center, artists and artisans came together primarily to limit the import of artworks from outside the city. This was generally accomplished by allowing only members of the local Guild of Saint Luke to sell paintings. Auctions of paintings brought in from elsewhere were forbidden except at the annual fairs (in Delft, the main public room of the town hall was used for this purpose). In exchange, member artists were required to pay an entrance fee of six guilders, which Vermeer, at the age of twenty-one, was unable to pay in full due, probably, to his uncertain economic condition at the time. The Guild of Saint Luke also played a significant role in not only promoting arts and crafts but also in connecting various interdisciplinary fields like art, science, optics, and philosophy.

"In effect, the Guild of Saint Luke was the perfect place for Vermeer to come into contact with other artists. Alongside painters, the guild counted glassmakers, potters, printers, tapestry makers, printmakers, and sculptors among its members. Artisans such as silversmiths, on the other hand, had a guild of their own. The management of the Guild of Saint Luke was made up of six headmen, with three new headmen elected each year.

At the time Vermeer joined, the guild did not yet have its own premises where the members could meet. The meetings probably took place in painters’ homes, or inns; quite possibly meetings may occasionally have been held in Mechelen, run by guild member Reynier Vermeer. In 1661, the guild obtained use of the former chapel building at the Oude Mannenhuis almshouses on the Voldersgracht. This building underwent considerable renovation, and headmen Cornelis de Man (1621-1706) and Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674) decorated the main hall on the first floor with murals and ceiling frescoes. A year later, Vermeer himself was elected headman for the first time. It must have been quite something for him to look out from the guild premises over to the rear of Mechelen, where he grew up."David de Haan, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Babs van Eijk, and Ingrid van der Vlis, Vermeer's Delft (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, Museum Prinsenhof Delft, 2023), 33.

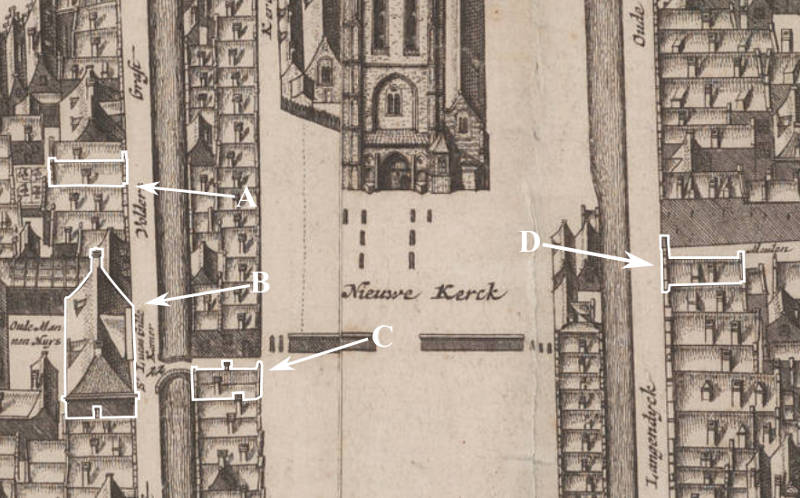

A. Flying Fox (Vermeer's presumed birthplace and inn of his father)

B. The Delft Guild of Saint. Luke (professional organization of artists and artisans)

C. Mechelen (a large tavern on the Market Square rented by his father where Vermeer and his family lived after the Flying Fox

D. Groot Serpent (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

E. Trapmolen (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

Apprenticeship

All guild members had to undergo a period of apprenticeship, which normally lasted from four to six years. This period spent in a recognized master-painter's workshop ensured the young artist a thorough familiarization with the complexities of his craft. We must remember that in Vermeer's time much of the artist's materials had to be produced by the painter in his studio, and painting techniques were far more elaborate than those of most modern artists. For example, paint was not sold in pre-prepared tubes as it is now. Each morning, the artist had to hand-mill the colors he intended for use in the day's painting. The process of hand-grinding paint presents a number of difficulties and requires much practice. This rather laborious task was often left to the apprentice, or in the case of highly productive artists, journeymen.

Training for a painter was expensive. On the average, the family of a young apprentice who lived with his parents paid between 20 and 50 guilders per year. Without board and lodging, up to one hundred guilder were needed to study with more famous artists such as Rembrandtvan Rijn (1606–1669) and Gerrit Dou (1613–1675). If we consider that school education generally cost two to six guilders a year and that apprenticeship generally lasted between four and six years, the financial burden of educating a young artist was considerable. Moreover, during the apprenticeship, the parents had to do without their son's potential earnings (female painters were trained by their fathers or husbands)since during this period the apprentice could not sign and sell his own paintings instead; all the works he produced became property of that master. Evidently, the allure of significant future earnings must have been significant.

Gerrit Lambert

1820

Graphite, pen and brown ink, brush and gray ink, 24.9 x 19.3 cm.

Gemeenarchief, Delft

In the master's studio, the apprentice was exposed to artistic theories and visiting artists' opinions which circulated with great fluency from one studio to the other. A number of Dutch painters had traveled to Italy to study the works of the Italian Masters. Their vivid accounts were no doubt the subject of long conversations. Painters' studios were often lively places frequented by artists, patrons and men of culture. Animated artistic debates as well as exchanges of information concerning the art market were the norm.

The young pupil was first instructed in drawing plaster casts of Classical sculpture. Many such casts can be seen in depictions of artists' studios; one, of a face, can be seen on the table in The Art of Painting by Vermeer. He next came to grips with the subtleties of representing a live model, and only afterward did he begin to use brush and paint. He sometimes was allowed to work on the less-important passages of his master's paintings, such as large areas of unmodulated backgrounds or monotonous areas of foliage in the background. The master closely followed his pupil's progress and corrected him when needed. Some extremely talented artists were able to leave the master's studio within a few years. Rembrandt progressed so rapidly that he already had pupils of his own at the age of twenty-one. As the apprentice's skills improved he worked on the more complex areas such as drapery and the secondary objects seen in a painting.

Once the apprentice had gained sufficient mastery, he was allowed to conceive and execute his own paintings, but could neither sign nor sell them. This could be done only after he had undergone the entrance exam of the guild. Another advantage of being a guild member was permission to sell paintings of other artists as well in order to augment his earnings. At the time of his death Vermeer had many paintings in his house which, according to a statement by his widow, he had bought and was unable to sell, thus incurring in grave financial losses. Unfortunately, not even the possibility of selling others' works was enough to offset a sharp decline in the art market in the last ten years of the artist's life.

Although Vermeer must have undergone an apprenticeship like every other painter in Delft, there is no evidence of whom he had studied with. For some time it was thought that Leonard Bramer (1596–1674), a native painter of Delft, might have been his master. This conjecture was based on more than one document, which suggests a certain familiarity between Vermeer and the elderly Bramer. But Vermeer's artistry seem to have little in common with that of Bramer's strongly Italianate style.

Recently, scholars have come to believe Vermeer studied outside of Delft, perhaps in Utrecht where his mother-in-law Maria Thins had relations with a well-established painter, Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), and other inhabitants of Utrecht. His mother-in-law Maria Thins, also possessed a number of paintings by Utrecht painters in her private collection. In any case, no documents have come to light that testify to Vermeer's presence either in Utrecht or Delft.

We do know, however, that Vermeer was admitted to the Guild on the December 29th of 1653 even though was not able to pay the entrance fee in full. His name can be seen on the register of the guild at number 77 (fig. 2). The names of Pieter de Hooch (80) and Carel Fabritius (75) also appear on the same document. On Saint Luke's Day, October 18th, 1662, the artists of Delft chose Vermeer to be the vice-dean of their guild, which would seem to be proof that at that time he must have been a respected artist and citizen. However, by the time Vermeer had been elected headmaster, many of the artists resident in Delft had left for the more prosperous Amsterdam, and so his election may have had less significance than usually thought.3

Photograph of the Guild of Saint Luke in 1879, shortly after Adriaan de Lint sold it to the municipality of Delft and was torn down.

"Given Vermeer's good name, we may presume that there was a demand for a training place with the innovative Delft master, and from an economic perspective, it must also have been attractive for Vermeer to have an assistant help him with his production. After his death, two easels were listed in his painting room, which in theory could accommodate a second painter alongside the master himself. We know of no written indication, however, of the presence of a student or assistant in his workspace, nor can the appealing idea that he was assisted as a painter by one or more of his daughters be substantiated with facts. Neither have his surviving paintings provided any evidence of the existence of a studio. Until recently, Vermeer experts were in agreement that it is not probable, given his small body of work, that the Delft painter led a workshop, but a research team at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, based on extensive multidisciplinary research into Girl with a Flute and Girl with a Red Hat, recently opened the door to the existence of a studio."Pieter Roelofs and Gregor Weber, VERMEER (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023), 213.

c. 1732

Leonard Schrenk

Engraving after a drawing by Abraham Rademaker made in 1700

Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden, Leiden

The Guild of Saint Luke was dissolved in 1833. It gradually fell into disrepair and pulled down in 1879. The Jan Vermeer elementary school was constructed in its place, which was recently cleared to make way for a scale reconstruction of the original guild. This building now houses the Vermeer Center ( (fig. 5; website: http://www.vermeerdelft.nl)