The Prinsenhof in Delft, originally the Agathaklooster (St. Agatha Monastery), represents a significant historical and architectural site that has evolved over centuries (fig. 1).The Agathaklooster, established in Delft in the early 15th century under the protection of Duke Albert of Bavaria and the bishop of Utrecht, flourished in its early years, housing up to 125 nuns, mostly from patrician families. However, the Protestant Reformation, economic decline, and criticism of the convent's wealth led to a steady decrease in membership. By the late sixteenth century, the convent faced fatal blows during the Beeldenstorm and the war against Spain, with its guest quarters serving as William the Silent's residence before his assassination in 1584. Membership dwindled to eight by 1607, and the last nun was buried in 1640. The monastery was established in the early fifteenth century as a residence for the Sisters of St. Agatha, a Catholic religious order.The Sisters of St. Agatha, named after the 3rd-century martyr St. Agatha of Sicily, were likely a localized religious order or congregation dedicated to charitable, educational, and devotional work. St. Agatha, venerated for her steadfast faith and associated with protection against fire and ailments, inspired communities to adopt her name and mission. These sisters often operated hospitals, cared for the poor, and educated girls in convent schools, reflecting the broader Catholic tradition of service. Particularly in regions like Sicily, where St. Agatha was a central figure of devotion, such groups were closely tied to local churches and their rituals. Their work exemplifies the significant role of female religious communities in shaping spiritual and social life during the medieval and early modern periods. Constructed in the Gothic style, the building initially featured a cloister layout, enclosed courtyards, high windows, and vaulted ceilings typical of ecclesiastical architecture. Its primary function was to serve as a place of worship and religious contemplation, with a chapel forming the centerpiece of the monastic complex.

Adriaen Thomasz. Key

1579

Oil on panel, 48 x 35 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The building underwent a profound transformation beginning in 1572, when William of OrangeWilliam of Orange was a leader in the struggle for Dutch independence during the Eighty Years' War. He had converted to Calvinism and became a staunch opponent of Spanish rule, challenging the authority of King Philip II of Spain. As a prominent Protestant leader, he was targeted as a heretic and traitor by the Spanish monarchy. In 1580, Philip II issued the Apology of William of Orange and placed a bounty of 25,000 gold crowns on William’s life. (1533–1584) (fig. 2), or Willian the SiIlent, leader of the Dutch revolt against Spanish rule, selected the site as his residence and administrative headquarters. "He chose the walled city of Delft because the traditional seat of government, The Hague, was open and not easy to defend. The nobles, soldiers, and officials in the prince's retinue formed a completely new kind of elite in this city of merchants and small-businessmen."Walter Liedtke, "Vermeer and the Delft School," in Walter Liedtke, Michiel C. Plomp, and Axel Rüger, Vermeer and the Delft School (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 198.

This period marked a turning point for the monastery, which was repurposed to accommodate secular functions. The architectural changes during this time were largely internal, with rooms restructured to create living quarters, meeting rooms, and offices suited to William’s needs as both a political and military leader. The chapel was likely converted for secular uses, but no major external reconstruction took place. Instead, the medieval Gothic structure was adapted, preserving its essential character.

Unknown author

17th century

Oil on canvas, 34.5 x 45 cm

Collectie Stadsarchief Delft (Municipal Archives), Delft

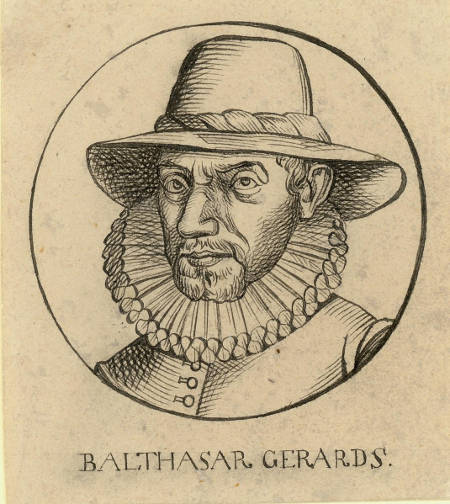

The Prinsenhof gained historical significance as the site of the assassination of William on July 10, 1584, by Balthasar Gérard (1557–1584) (fig. 3) an agent of King Philip II of Spain. Gérard shot William on the staircase leading to his office, and the bullet holes from this event remain visible near the main staircase, serving as a poignant reminder of the building’s role in Dutch history. Gérard had arrived in Delft under the guise of a French nobleman seeking refuge. On July 10, 1584, he gained access to the Prinsenhof, William's residence in Delft with two wheel-lock pistols concealed beneath his clothing. As William descended the stairs after dining, Gérard approached and shot him at close range (fig. 4). According to accounts, William’s last words were reportedly, "My God, my God, have pity on me and on this poor people." Gérard fled the scene but was quickly apprehended. His trial and subsequent execution were marked by extraordinary brutality, even by the standards at the time. Gérard was tortured and subjected to a public execution, which included having his hand burned off, being disemboweled, and finally being quartered. Despite the gruesome punishment, Gérard reportedly remained convinced of the righteousness of his actions, seeing himself as a martyr for Catholicism and the Spanish cause.Philip II gave Gérard's parents, instead of the reward of 25,000 crowns, three country estates in Lievremont, Hostal, and Dampmartin in the Franche-Comté, and the family was raised to the peerage. Philip II would later offer the estates to Philip William, Orange's son and the next Prince of Orange, provided the prince continue to pay a fixed portion of the rents to the family of his father's murderer; the insulting offer was rejected. The estates remained with the Gérard family. The apostolic vicar Sasbout Vosmeer tried to have Gérard canonized, to which end he removed the dead man's head and showed it to church officials in Rome, but the idea was rejected.

Jan Luyken

1678–1680

Pen and ink on paper, 21 x 29 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

William’s assassination marked a crucial moment in the Dutch fight for independence, and the Prinsenhof became emblematic of this struggle, and was a significant setback for the Dutch Revolt, even though it did not halt the broader push for independence. William had been a unifying figure, and his death led to a leadership vacuum. However, his son, Maurice of Nassau (1567–1625), assumed command and continued the fight, further solidifying the Dutch Republic's resistance against Spanish authority. The assassination also marked a turning point in the perception of regicide. While Gérard considered himself a devout Catholic carrying out God’s will, his actions provoked widespread fear and condemnation. The use of assassination as a political tool in the context of religious wars underscored the volatility and moral complexities of the era.

After William’s death, the Prinsenhof transitioned through various civic and public roles. In the seventeenth century, it served as a Latin school, providing education to the local population. By the eighteenth century, the building was repurposed as a cloth hall, playing a role in the economic life of Delft as a center for trade and civic gatherings. Later, it was used as a military barracks, reflecting the practical needs of the time. These changes were incremental, involving adjustments to the interior and the removal or expansion of certain wings. However, the structure retained much of its Gothic and early Renaissance character, blending elements of its monastic origins with later civic functions.

In 1616, the Prinsenhof became home to the Latin School of Delft, known as the Latijnse School.The Latijnse School at the Prinsenhof in Delft was a prominent educational institution during the early modern period, reflecting the humanist emphasis on classical education. Housed in the Prinsenhof,, the school prepared boys from patrician and merchant families for university studies or careers in law, medicine, theology, and public service. The curriculum focused on Latin, Greek, and sometimes Hebrew, with instruction rooted in classical texts by authors like Cicero and Virgil, as well as Christian theology. Latin Schools like this one were essential in fostering intellectual development and civic leadership during the Dutch Golden Age, aligning education with the cultural ambitions of cities like Delft, a center of art, science, and trade. This institution was crucial in providing classical education to the youth of the city, primarily preparing them for university studies. The curriculum focused on Latin, Greek, theology, philosophy, and rhetoric. Notable educators, such as Rector Reinier Bontius, played significant roles in shaping the intellectual landscape of Delft during this period.

In 1621, "part of the Prinsenhof was given over to the company to use as its administrative offices and warehouse. The Merchant Adventurers took advantage of the proximity of The Hague to promote its interests with the king of England. In August 1623 and April 1624, for example, the company hosted huge celebrations in the Prinsenhof honoring Elizabeth Stuart, the daughter of King James I, and her consort, King Frederick V of Bohemia."Marten Jan Bok, "Society, Culture, and Collecting'," in Walter Liedtke, Michiel C. Plomp, and Axel Rüger, Vermeer and the Delft School (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 203.

Between 1667–1669, the city of Delft paid Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674), Delft's most venerable artist at the time, for decorating the large meeting room Grote Zaal (Great Hall) of the Prinsenhof with canvas murals, which, perhaps, stands as his crowning achievement. "To judge from Augustinus Terwesten's later drawing of the room, the main scene appears to have been, once again, a festival set in a city square, namely, the Roman games to which the Sabines were invited. During the late 1650s or early 1660s, Bramer made a series of fifty drawings illustrating Livy's History of Rome, in which The Rape of the Sabines is included. On the long (north) wall, Bramer represented imaginary Roman architecture and what appears to be a running narrative, with a meeting of mounted and standing figures on the left, the Roman surprise in the center, and two or three armored horsemen carrying off women to the right. Why this subject would have been considered suitable for a public meeting and (presumably) banqueting room requires further clarification. That the story involves the founding of a republic does not seem explanation enough. While much had changed in the art world of Delft since the earlier decades of [seventeenth] century, Bramer's murals are an example of strong continuity between the 1630s and 1660s."Walter Liedtke, "Painting 'In Perspective'," in Walter Liedtke, Michiel C. Plomp, and Axel Rüger, Vermeer and the Delft School (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 123.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the economic focus of Delft had shifted towards trade and industry. In 1749, the Prinsenhof was repurposed as a cloth hall, or Lakenhal, aligning with the city's prominence in the textile industry. The cloth hall functioned as a bustling trade center where merchants gathered to buy and sell textiles, facilitating both local and international commerce. It also served as a place for quality control, where cloth was inspected and measured to ensure it met the required standards. Additionally, it became an economic hub that hosted auctions and trade fairs, attracting traders from across the Netherlands and Europe.

With the advent of the French Revolutionary Wars and the subsequent Napoleonic Wars from 1792 to 1815, the need for military facilities increased. Around 1795, during the French occupation of the Netherlands, the Prinsenhof was converted into military barracks. The building housed French troops from 1795 to 1813, reflecting the strategic importance of Delft. After the restoration of Dutch independence in 1813, the Prinsenhof continued to serve military purposes for the Dutch army. Interior spaces were altered to accommodate soldiers, including the creation of dormitories, mess halls, and training areas.

Throughout these transitions, the Prinsenhof underwent various architectural modifications. Interior adjustments involved removing or adding walls to create larger halls or smaller rooms, depending on the building's function at the time. Certain sections were expanded to provide more space for military drills or storage, while others were demolished due to disrepair or to suit new purposes. Despite these changes, key historical features were preserved. Notably, the staircase where William of Orange was assassinated remains intact, with the bullet holes from the assassination still visible—a poignant reminder of the building's historical significance.

Recognizing the historical importance of the Prinsenhof, efforts were made in the early twentieth century to preserve it as a cultural heritage site. In 1897, parts of the building were first opened to the public as a museum. By 1911, the entire Prinsenhof was officially established as the Gemeentemuseum Het Prinsenhof (Municipal Museum The Prinsenhof). The museum’s focus is on the history and art of Delft, with three primary themes: William of Orange, Delft Blue pottery, and the Delft Masters. Its collections include Dutch Golden Age paintings, prints, ceramics, and contemporary art, highlighting the cultural and artistic contributions of Delft to the Netherlands’ heritage. Efforts to restore the building during this period aimed to preserve its historical significance, emphasizing its layered history rather than extensively modifying its structure. Records of specific architects involved in the restoration are limited, suggesting that much of the work was carried out with a conservationist rather than an innovative approach.

Architecturally, the Prinsenhof is a blend of Gothic monastic design and Dutch Renaissance adaptations. The exterior features characteristic brickwork, high windows, and stepped gables, while the interior retains elements such as vaulted ceilings and cloister-like courtyards. Despite modifications over the centuries, the building remains a testament to its original purpose as a monastery and its later roles in Dutch civic life.

Today, the Prinsenhof stands as a symbol of Delft’s rich historical and cultural heritage. It is recognized as one of the Cultural Heritage Agency’s top 100 listed buildings, reflecting its significance in the Netherlands' architectural and historical landscape. The building not only encapsulates the evolution of Dutch society but also serves as a tangible link to pivotal moments in the nation’s history, from the religious devotion of the medieval period to the political upheaval of the Dutch Revolt. Its layered functions and preserved architectural elements make the Prinsenhof a unique monument to the interplay between history, architecture, and civic identity.