Oude Mannenhuis

The Oude Mannenhuis (Old Men's Home) in Delft, established during the seventeenth century on Voldersgracht, reflects the societal priorities and charitable practices of the Dutch Republic during its Golden Age. This institution was created to provide care and shelter for elderly men who lacked the financial means or familial support to sustain themselves. It stands as an example of the structured welfare initiatives that emerged in response to the growing urban population and the challenges associated with aging and poverty.

Archaeological surveys of this site have exposed a series of latrines and a lot of earthenware finds from the fifteenth century, mainly remnants of cooking utensils and crockery. These are relatively cheap, utilitarian items such as jugs, bowls for drinking, and chamber pots, clearly related to the site’s longstanding role as a place of care for the elderly. A great deal of value was placed on people being able to read the Bible for themselves."David de Haan, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Babs van Eijk, and Ingrid van der Vlis, Vermeer's Delft (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, Museum Prinsenhof Delft, 2032), 123.

The daily diet of the residents at the Oude Mannenhuis, an almshouse for elderly men in Early Modern Delft (1411–1792), was examined Merit HondelinkMerit Hondelink, "Aan tafel in het Oude Mannenhuis te Delft," Paleo-Aktueel, December 2018, DOI:10.21827/PA.29.103-114. by integrating evidence from historical food-purchase records and archaeobotanical analysis of macro remains found in cesspits. It was discovered that the steward's records suggest a diet that was frugal and monotonous, seemingly devoid of common food items such as fruits, vegetables, herbs, and spices typically consumed during the Medieval and Early Modern periods. However, archaeobotanical findings reveal the presence of at least fortey-three edible plant species, indicating a far more diverse diet than the historical records suggest. Most of these plants were locally grown in and around Delft, though some exotic species were also identified. By combining these sources, a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the daily meals consumed by the residents of the Oude Mannenhuis emerges.

The home served a dual purpose: offering protection to vulnerable individuals while maintaining public order by addressing the visible needs of the elderly poor. Admission was typically granted based on specific criteria, such as age, lack of income, and sometimes a demonstration of moral character, ensuring that the assistance was directed to those deemed deserving. Priority was often given to local residents of Delft, reflecting a sense of communal responsibility within the city.

The building itself was likely designed with practicality in mind, incorporating communal spaces such as dormitories, dining halls, and gardens. These facilities were organized to support a modest and disciplined lifestyle, aligning with the Protestant values of thrift, order, and morality that characterized much of Dutch society at the time. The residents, many of whom were former tradesmen or laborers, lived under a structured routine aimed at maintaining harmony within the institution.

Charitable institutions like the Oude Mannenhuis were supported through a combination of private philanthropy and municipal funding. Wealthy citizens, guilds, and civic leaders often contributed to such efforts, motivated both by religious principles and a desire to reinforce social stability. These homes symbolized the balance between altruism and pragmatism that underpinned much of the social policy in the Dutch Republic.

While the Oude Mannenhuis itself may not have been directly depicted in the works of renowned Delft artists such as Vermeer, the cultural ethos of the time, which emphasized ordinary life and the dignity of all individuals, resonates in the art and records of the period. Archival documents offer glimpses into the daily lives of the residents and the operational structure of the home, highlighting its role as both a sanctuary and a microcosm of the city’s social order.

The legacy of institutions like the Oude Mannenhuis is significant, as they set a precedent for organized elder care that extended into modern welfare systems. The model of blending private charity with public responsibility demonstrated an early recognition of the societal obligation to provide for those unable to care for themselves.

"At the time Vermeer joined, the guild didn’t yet have its own premises where the members could meet. The meetings probably took place in painters’ homes or inns; quite possibly meetings may occasionally have been held in Mechelen, run by guild member Reynier Vermeer, Vermeer's father. In 1661, the guild obtained use of the former chapel building at the Oude Mannenhuis almshouses on. This building underwent considerable renovation, and headmen Cornelis de Man (1621-1706) and Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674) decorated the main hall on the first floor with murals and ceiling frescoes. A year later, Vermeer himself was elected headman for the first time. It must have been quite something for him to look out from the guild premises over to the rear of Mechelen, where he grew up."David de Haan, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Babs van Eijk, and Ingrid van der Vlis, Vermeer's Delft (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, Museum Prinsenhof Delft, 2032), 33.

De Visbanken

Gerrard Dukker

Juky, 1964

Photograph, dimensions unknown

Rijksmonument, Delft

The Visbanken (Fish Market) in Delft, is a historic structure located in the city's center on the corner of the Camaretten and Hippolytusbuurt (Cameretten 2).The Visbanken operates from Tuesday to Friday between 9:00 AM and 6:00 PM, and on Saturdays from 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM. It remains closed on Sundays and Mondays. Architecturally, it comprises columns supporting a wooden roof, a design characteristic of the eighteenth century. The building is adjacent to the western façade of the Vleeshal, situated at the corner of Hippolytusbuurt. Currently, the Visbanken functions as a fish shop and delicatessen, offering a variety of seafood products.As a site of historical significance, the Visbanken is recognized as a national monument in the Netherlands. Its enduring function as a fish market underscores its continuous role in Delft's commercial activities.The establishment emphasizes quality and sustainability in its offerings. Customers can expect excellent service, a relaxed atmosphere, and well-presented products.

The Visbanken was a vital institution in the city’s economic and social life during the seventeenth century. As the primary marketplace for fish, it played a central role in connecting the local population with the broader fishing and maritime industries that supplied fresh and preserved seafood. Located near Delft’s canals, the Visbanken was strategically positioned to facilitate the transport and sale of fish brought in from the North Sea and nearby waters.

The operations of the Visbanken were tightly regulated by municipal authorities to maintain quality and order. Inspectors were tasked with ensuring that the fish sold was fresh and free from spoilage, safeguarding public health and consumer trust. Standardized pricing and licensing requirements for vendors further contributed to the market's structured environment. These measures reflected Delft's commitment to creating an orderly and reliable trading system, a hallmark of Dutch urban governance during the seventeenth century.

Beyond its economic function, the Visbanken served as a gathering place for the community. The market brought together residents of Delft, providing a space not only for commerce but also for social interaction. The lively atmosphere of the fish market was a reflection of the city's daily rhythms, where negotiation, conversation, and the exchange of goods reinforced social connections.

The market was designed to be both practical and efficient. Its semi-covered or open structure included stone benches or counters where vendors displayed their goods. This layout ensured that fish could be handled hygienically while also allowing easy access for both merchants and customers. The canals nearby enabled the swift delivery of fish directly from the fishing fleets, highlighting the market’s integration into Delft’s urban and maritime infrastructure.

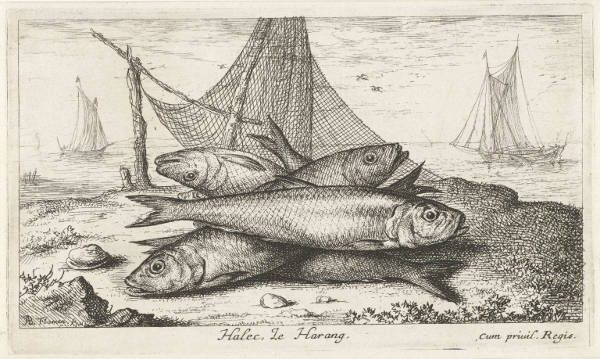

Fishing

Albert Flamen

1664

Etching on paper, 10.5 x 18 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In the seventeenth-century Netherlands, sea fishing was a vital industry employing several specialized techniques and vessel types. The primary methods included drift netting, which involved deploying long nets that drifted with the current, capturing fish as they swam into them. This method was particularly effective for herring, a staple of the Dutch fishing industry. Another common method was longlining, which utilized extensive lines equipped with numerous baited hooks to target species like cod. Longlining allowed fishermen to catch large quantities of fish over wide areas. Trawling, which involved dragging a net through the water column or along the seabed to capture fish, was less common than drift netting and longlining but was employed for certain species and in specific regions.

The vessels used in Dutch sea fishing were also highly specialized. The haringbuis (herring buss),The herring buss was a type of fishing vessel widely used in the Netherlands from the 15th to the 19th century, instrumental in the Dutch herring trade. Designed for open-sea fishing, it featured a broad, sturdy hull and was equipped with drift nets for catching herring in large quantities. The buss allowed crews to process and preserve the catch onboard using the innovative gibbing technique, which removed the gills and part of the gullet while retaining the liver and pancreas to enhance flavor during salting. This capability enabled extended fishing expeditions and contributed to the Dutch dominance in the North Sea herring trade, making the herring buss a symbol of the maritime and economic success of the Dutch Golden Age. designed specifically for herring fishing, was approximately 20 meters in length and displaced between 60 and 100 tons. It featured a broad deck for processing the catch and was equipped with two or three masts, enabling extended voyages to follow herring shoals far from the Dutch coast. Another type of vessel, the dogger,The dogger was an early type of fishing vessel used in the North Sea, dating back to the Middle Ages. It was a small, sturdy, and versatile boat designed for fishing cod and other species in the often harsh conditions of the open sea. Typically around 15 meters in length, the dogger was equipped with a single mast and a square sail, along with space for oars to assist in maneuvering. These vessels carried drift nets and were capable of staying at sea for extended periods, making them well-suited for deep-sea fishing. The term "dogger" later evolved to refer to a specific fishing bank in the North Sea, the Dogger Bank, which remains one of the most productive fishing grounds in the region. was primarily used for cod fishing. These boats, about 15 meters long with a maximum beam of 4.5 meters and a draught of 1.5 meters, were sturdy and capable of operating in the rough conditions of the North Sea.

Anonymous

c. 1615–1620

Etching on paper, 37.1 x 51.7 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

These fishing methods and vessel designs were integral to the Dutch fishing industry, contributing significantly to the economy and sustenance of the population during the seventeenth century.

Both sea and freshwater fish could be found at the Visbanken. Sea fish, often brought in from larger ports connected to the North Sea, included herring, cod, and mackerel. Herring, in particular, was a staple in Dutch cuisine and economy due to its abundance and the efficiency of Dutch fisheries and curing methods, such as gibbingGibbing is a technique for preparing and preserving herring, developed in the 14th century. It involves removing the gills and part of the gullet while leaving the liver and pancreas intact during the salting process, as these organs release enzymes that enhance the fish’s flavor. This innovative method is credited to Willem Beukelszoon, a fisherman from Biervliet in the Netherlands. Gibbing revolutionized the herring trade by significantly extending the fish’s shelf life, allowing it to be transported over long distances and establishing herring as a vital commodity in the Dutch economy. CodCod fishing in the North Sea has been an essential part of the regional economy for centuries, but modern practices and concerns about overfishing have led to stricter regulations to ensure sustainable stocks. Today, cod preparation often follows more standardized commercial methods, but historical gibbing remains a notable part of the fishing heritage in the region. was also a common catch, valued for its versatility and ability to be preserved through salting or drying, while mackerelMackerel fishing in the North Sea during the 17th century was an important seasonal activity, with the fish prized for its abundance and nutritional value. Mackerel, being a highly migratory species, was caught in large numbers as it moved closer to the coasts during spawning periods. The fishing methods of the time typically involved the use of drift nets or hand lines from small boats. Due to the lack of refrigeration, mackerel was processed immediately after being caught, often by salting or smoking, to prevent rapid spoilage caused by its high oil content. The fish played a significant role in local diets and trade, contributing to the maritime economy of coastal communities in the Netherlands, England, and other North Sea regions. was consumed fresh or salted.

Jacob Gillig

c. 1684

Oil on panel, 47.3 x 39.4 cm

Private collection

Pieter van Noort

c. 17th century

Oil on canvas, 65.6 x 78.9 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Still life with various types of fish (carp, perch) displayed on a fishing net at the corner of a table. In the background, a fishing rod with a line and float, and a bucket.

Freshwater fish were sourced from the canals, rivers, and lakes surrounding Delft and the wider Dutch countryside. Common varieties included pike, perch, carp, and eel. Eel,Eel was a popular and widely consumed food in 17th-century Netherlands, enjoyed by all social classes and frequently depicted in Dutch art. Abundant in the country's rivers, canals, and brackish waters, eel was often smoked for preservation or grilled, stewed, or baked into pies. Its rich flavor and ease of preparation made it a staple of the Dutch diet, with smoked eel particularly prized for its portability and shelf life. The trade and consumption of eel reflected the Netherlands’ strong maritime economy and connection to water, while its inclusion in genre paintings by artists like Jan Steen symbolized everyday life and indulgence during the Golden Age. especially, was a delicacy in the Netherlands and was often smoked for preservation and added flavor. The weekly freshwater fish market at the bridge at the end of Nieuwstraat catered to those seeking locally caught freshwater species.

Fish consumption varied across social classes, reflecting economic disparities and cultural preferences. Wealthier individuals often consumed sea fish such as herring, eel, plaice, and cod, which were supplied daily from Scheveningen.Scheveningen, a district of The Hague in the Netherlands, has evolved from a modest fishing village into a prominent seaside resort. The earliest recorded mention of Scheveningen dates to around 1280, referred to as "Sceveninghe." By the 14th century, fishing had become a primary occupation for its inhabitants These fish were integral to the local diet and economy, reflecting the city's connection to maritime trade and fishing activities.

In contrast, the lower classes primarily consumed freshwater fish, which were more accessible and affordable. Species such as pike, perch, carp, and eel were commonly available in local markets. The weekly freshwater fish market on the bridge at the end of Nieuwstraat catered to those seeking locally caught freshwater species.

Herring, in particular, held special economic and cultural significance. Its availability year-round and the innovation of curing techniques made it a cornerstone of the local diet and an important trade commodity. The market ensured that fish remained accessible to the population, reinforcing its importance as a staple food, particularly during periods of religious fasting when meat consumption was restricted.

De Waag

De Waag in Delft, located behind the Stadhuis on the west side of the Markt, is a historic building with origins tracing back to at least 1539.The building continued to serve as a weigh house until 1960, after which it was repurposed for different uses, such as a bicycle storage facility and a theater. Since 1999, De Waag has functioned as a café-restaurant, allowing visitors to experience its historical ambiance while enjoying modern hospitality Initially serving as the city's weigh house, it played a crucial role in regulating trade by ensuring accurate measurements of goods, thereby promoting fair commerce.

Jan Bulthuis

Drawing on paper

The Waag was a central institution in the city's economic infrastructure. Constructed to facilitate the official weighing of goods, it ensured fair trade practices and accurate taxation. Merchants were obligated to have their commodities weighed by certified officials, which helped maintain standardized measurements and prevent fraud. It was strategically located to accommodate the flow of goods coming into the city, particularly those transported via the extensive canal system. Its operation was overseen by municipal authorities, who were responsible for maintaining the accuracy of the scales and enforcing market regulations. This institution played a crucial role in sustaining the economic vitality of Delft by supporting its trading activities and ensuring trust in commercial transactions.

The building underwent significant modifications over the centuries. In 1644, the municipality acquired an adjacent property, expanding the Waag to accommodate a larger weighing scale, which remains in place today and bears the year 1647. A major renovation in 1770 unified the two structures under a single façade, resulting in the building's current appearance.

Beyond its primary function, the Waag's upper floors hosted various guilds, including the gold and silversmiths' guild in 1674 and later the physicians' and apothecaries' guild, as indicated by a stone on the rear façade.

Architecturally, the Waag exemplified Dutch Renaissance design, featuring ornate façades and gabled roofs that reflected the prosperity of the period. The building not only served a practical purpose but also stood as a testament to Delft's importance in regional and international trade during the Dutch Golden Age.

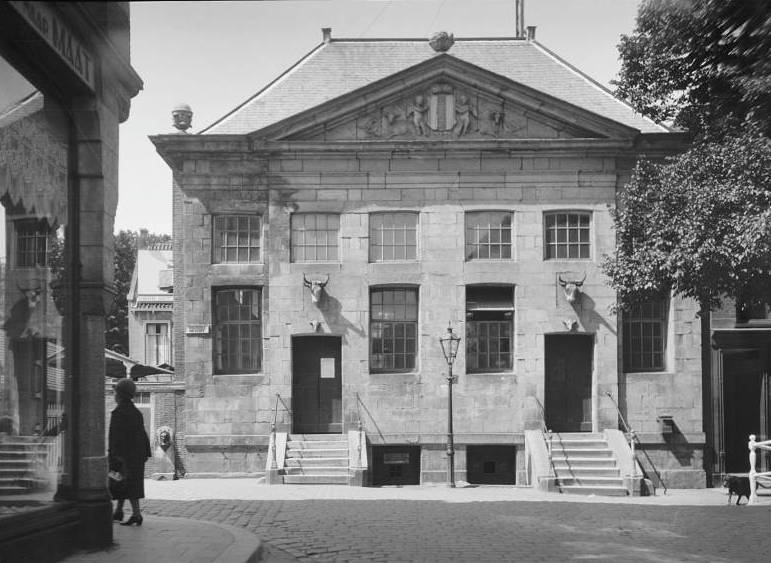

Vleeshal (Meat Hall, now called Koornbeurs)

In seventeenth-century Delft, the Vleeshal (Meat Hall), was a significant municipal edifice dedicated to the regulation and sale of meat products. The Vleeshal was the only place where butchers were permitted to sell their meat in Delft. "The big building with the ram and ox heads—the horns on which are from real animals—has hardly changed. There would have been a trellis in the windows instead of glass back then. That was for ventilation, with all that meat on sale there, and to stop birds from getting at it."David de Haan, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Babs van Eijk, and Ingrid van der Vlis, Vermeer's Delft (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, Museum Prinsenhof Delft, 2032), 129.

C. Hoogendijk

c. 20th century

Photograph, dimensions not provided

Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, Delft, Netherlands

The original structure, dating back to 1295, was reconstructed in 1650 atop its medieval cellar, under the design of architect Hendrick Swaef. This reconstruction was part of a broader urban development initiative that included the establishment of new neighborhoods and civic buildings, thereby contributing to Delft's distinctive character during this period.

Architecturally, the Vleeshal featured a high ceiling supported by four sandstone columns, exemplifying the Dutch Classical style. The building's façade was adorned with carvings of a bull and calf above the two front entrances, symbolizing its function in the meat trade.

The Vleeshal's role extended beyond commerce; it was integral to the city's economic and social fabric. Municipal oversight of meat trading within the hall ensured quality control and fair pricing, reflecting the regulatory practices of the time. The establishment of such specialized marketplaces was common in Dutch cities during the Golden Age, underscoring the importance of organized trade and public health.

The Vleeshal is emblematic of Dutch Golden Age architecture, blending functional design with ornate embellishments that were characteristic of public buildings in this period. Located in the city center, the building is notable for its use of natural stone and red brick, accentuated with intricate gables and sculptural details. Its design reflects the economic prosperity of Delft during the seventeenth century and stands as a testament to the city's skilled craftsmanship and urban planning.

Scholars and visitors frequently regard the Vleeshal as a case study of how urban spaces were designed to accommodate both economic and aesthetic goals. It also provides insight into the social and regulatory frameworks of food trade and public health in historical contexts, reflecting broader societal norms of the time.

Although it initially served as a meat market, the function of the Vleeshal has evolved, and it was repurposed multiple times. Today, it is often admired as an example of preserved historical architecture, contributing to the understanding of civic and commercial life in early modern Delft.