The Evolution and Production of Delftware

Delftware (Dutch Delfts aardewerk or simply Delfts) includes objects of all descriptions, such as plates, vases, figurines and other ornamental forms and tiles. The term "Delft Blauw,"This term refers specifically to Delftware decorated with blue designs on a white tin-glazed background. The style was inspired by Chinese porcelain and became highly popular in the Netherlands during the 17th century. The blue coloration is achieved using cobalt oxide, which turns blue upon firing. is used to distinguish it from other other Delft pottery production that employs other colors (fig. 1). However, "the elaborate pieces of Delftware displayed today in museums or private collections were ornamental. They represent only a small part of the output of the Delftware kilns. The larger part consisted of plain or very simply decorated pottery for household use, and tiles for wall decoration."Walter Liedtke, Vermeer and the Delft School (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 193.

Anonymous (Delft), after Nicolaes Pieterszoon Berchem (1621/1622–1683)

c. 17th century

Faience, H. 24.5 x W. 30 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

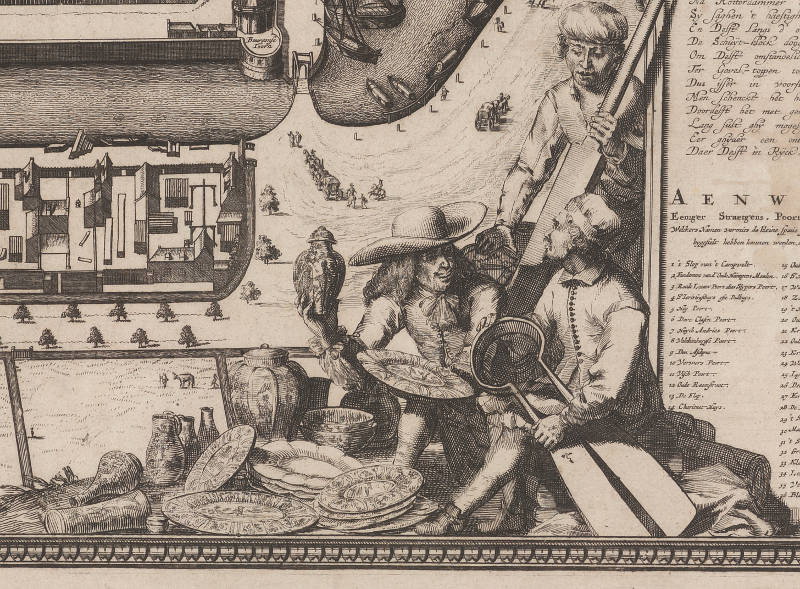

"How proud Delft was of its earthenware industry can be seen on the Kaart Figuratief,The Kaart Figuratief of Delft refers to a detailed cadastral map created in 1675 to document the city’s landholdings and municipal properties. Commissioned by Delft's magistrates, it served as an administrative tool for managing the city's land assets and ensuring accurate records for taxation and urban planning. Unlike standard maps, the Kaart Figuratief is notable for its detailed depiction of individual parcels, buildings, and surrounding landscapes, rendered with artistic precision and decorative elements. This map not only reflects the technical and artistic capabilities of Delft’s cartographers but also provides a valuable historical record of the city’s layout, economic activity, and municipal organization during the late 17th century. near the map's lower right-hand corner, where a man is shown wearing a broad-brimmed hat and displaying an assortment of Delftware plates, jars, and jugs–though no tiles (fig. 2). Indeed, despite the term 'Delft tiles', tile-making went on in other parts of the country, too–for instance, in Makkum, Friesland—though those that were made in Delft were less mass-produced and more artful."Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2002), 174.

Published in Delft by Dirck Evertsz. van Bleyswijck

1675–1678

81.5 (82.5) x 124.5 (125.5) cm.

"Experiments were conducted with native clay to imitate the Eastern product as closely as possible, which was achieved fairly quickly. These attempts were mainly made in Delft and Rotterdam and once they succeeded, the number of companies in these cities expanded significantly. Ultimately there were twelve factories in Rotterdam and no fewer than thirty factories in Delft. It is not entirely clear why Rotterdam and Delft came to the fore so strongly in the production of porcelain, but in the case of Delft, it may have had something to do with the number of vacant buildings, as a result of the demise of several breweries in the city.""History," Royal Delft Museum, accessed November 27, 2024, https://museum.royaldelft.com/en/discover-the-collection/history/.

The abrupt cessation of the Chinese porcelain supply in these years was also an important catalyst for Delftware and its eventual dominance was devoted to the imitation of the widely coveted Asian commodity.Christina An and Menno Fitski, "Vermeer's Jar," The Rijksmuseum Bulletin 71, no. 2 (2023). But to rival the original Chinese Kraak, many technical improvements had to be made. The use of marl, a type of clay rich in calcium compounds, allowed the Dutch potters to refine their technique and to make finer items. The usual clay body of Delftware was a blend of three clays, one local, one from Tournai and one from the Rhineland.Alan Caiger-Smith, Tin-Glaze Pottery in Europe and the Islamic World: The Tradition of 1000 Years in Maiolica, Faience and Delftware (London: Faber and Faber, 1973), 130. From about 1615, the potters began to coat their pots completely in white tin glaze instead of covering only the painting surface and coating the rest with clear ceramic glaze. They began to cover the tin-glaze with clear glaze, which gave depth to the fired surface and smoothness to cobalt blues, ultimately creating a good resemblance to porcelain, although when chipped, the reddish earthenware was clearly exposed.Alan Caiger-Smith, Tin-Glaze Pottery in Europe and the Islamic World: The Tradition of 1000 Years in Maiolica, Faience and Delftware (London: Faber and Faber, 1973), 129.

The production of Delftware involved a meticulous multi-step process, each requiring specialized skills. Below is an outline of the production stages along with the corresponding Dutch and English terms for the craftsmen involved.

The Process: The Difficulties in Imitating Chinese Kraak

Imitating the highly sought-after Chinese Kraak porcelain presented significant challenges for Delft Majolica potters, who needed to compete in a market captivated by the thinness, clarity, and sheen of these imported wares. The coarse, impure clay traditionally used in majolica production was ill-suited for replicating the thinness of porcelain. When made thinner, the pieces warped during drying and shrank excessively during firing. To address this, potters began mixing local clay with imported varieties from Tournai and refined it through sieving and washing. This process produced a higher-quality clay that was less prone to shrinkage, enabling the creation of thinner and more versatile earthenware. The use of molds further enhanced their ability to replicate the scalloped edges and uniformity of Chinese dishes, increasing both efficiency and fidelity to the porcelain forms.

The glazing process posed additional difficulties. Majolica relied on tin glaze for its white, opaque finish and lead glaze for less visible areas. However, to replicate porcelain’s natural white appearance, potters had to coat the entire piece in tin glaze after the initial biscuit firing. This increased production costs significantly, as tin glaze was expensive. To achieve the glossy sheen of porcelain, a secondary clear glaze known as kwaart—derived from the Italian term coperta—was applied over the tin glaze before firing. This not only enhanced the visual appeal but also provided better protection to the finished piece.

Another major challenge was eliminating the characteristic spur marks left by traditional majolica firing methods. Potters originally used tripod spurs to stack pieces in the kiln, which left blemishes on the surface. Since Chinese porcelain had no such marks, an alternative firing method was needed. They adopted an Italian saggar technique, placing the plates in cylindrical containers with ceramic pegs that supported the pieces. This method reduced marks to the back rims and protected the pottery from soot, ash, and uneven heat. The interior of the saggars was coated with lead glaze and carefully sealed with clay to ensure the glossy component did not evaporate or absorb into the container during firing. While effective, this technique required meticulous preparation and added further complexity to the production process.

The potters also had to adapt their decorative techniques to mimic the aesthetic of Chinese Kraak porcelain. They shifted to blue-and-white designs with borders featuring Chinese symbols and plants, while central areas often depicted scenes reminiscent of Wanli-period porcelain. These changes required skilled painting with in-glaze techniques, where decorations were applied before firing to fuse with the glaze. Despite these innovations, the transition was not immediate or uniform. Some objects still bore spur marks or only partial tin glazing, reflecting the gradual implementation of new methods.

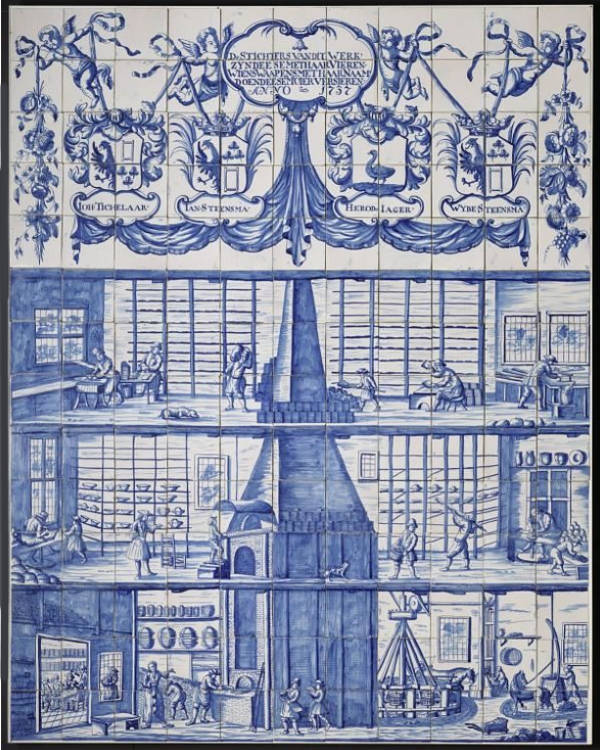

Attributed to Dirk Danser

c. 1745–1765

Tin-glazed earthenware (faience), H. 182.5 x W. 144 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Through these combined efforts, Dutch potters successfully overcame significant technical and artistic hurdles to create a compelling imitation of Chinese porcelain, giving rise to a distinctly European ceramic tradition that blended innovation with homage to the exotic wares they sought to emulate (fig. 3).

Clay Preparation (Kleibereiding)

The production of Delftware involved a meticulous multi-step process, each requiring specialized skills (fig. xx). Below is an outline of the production stages along with the corresponding Dutch and English terms for the craftsmen involved.

Clay washers (Kleiwasserijen) were responsible for mixing and purifying various clays, including local clay, fattier clayFat clay refers to a type of clay that is rich in fine particles and has a high plasticity, meaning it is very moldable and retains its shape well when worked. It is called "fat" because it feels smooth, greasy, or sticky to the touch due to its high water content and cohesive properties. This type of clay is often used in pottery and ceramics because it can be easily shaped on a wheel or by hand, making it ideal for creating detailed forms. from Germany, and dry marl from regions like Tournai or England. This combination allows for the creation of thin earthenware objects. The refinement of this clay mixture was conducted at specialized facilities known as clay washeries. At these establishments, the raw clays were combined with water to create a liquid suspension. This mixture was then passed through fine copper sieves to remove impurities and achieve a uniform consistency. The resulting suspension was collected in trays, where it was allowed to settle and partially dry. Once it reached the appropriate stiffness, the clay was cut into square blocks and transported to pottery workshops for further processing."How Was Delftware Made?" Dutch Delftware. Accessed November 27, 2024. . Upon arrival at the pottery, the clay blocks were stored in masonry pits and periodically moistened to maintain their pliability. A worker known as the aardetrapper (earth treader) would then knead the clay with his bare feet to ensure uniform texture and remove air pockets. This manual kneading was crucial for preparing the clay for shaping and forming into various Delftware items."The Production Process of Delftware According to Paape." Aronson Antiquairs of Amsterdam. Accessed November 27, 2024/.

Shaping (Vormen)

The Draaier (thrower) shaped the clay on a potter's wheel to create various forms. He was responsible for creating symmetrical, circular items such as plates, bowls, and vases. The process began with the draaier centering a prepared lump of clay on potter's wheel, powered by foot. "This wheel featured a large flywheel located below the working surface, which the draaier would spin using a foot pedal. This manual mechanism allowed the artisan to control the wheel's speed and maintain a consistent rotation, essential for shaping clay into symmetrical forms such as plates, bowls, and vases. The foot-powered design enabled the draaier to use both hands freely to manipulate the clay, ensuring precision and uniformity in the crafted pieces. Through skilled manipulation, the draaier would then draw up and shape the clay into the desired form, ensuring uniform thickness and smooth surfaces."Kees Kaldenbach, "How Did They Produce Delft Blue Faience or 'Delft Porcelain' in the Delftware Potteries?" Accessed November 27, 2024. This stage was fundamental, as the quality of the thrown piece directly influenced the final product's integrity and aesthetic. After throwing, the items were dried to a leather-hard state, allowing for further refinement and the addition of decorative elements before the initial firing. Components like knobs and handles would be shaped by hand and stuck on using clay slurryclay (kles)."How Was Delftware Made?" Dutch Delftware. Accessed November 27, 2024. https://delftsaardewerk.nl/en/discover/how-was-delftware-made.

The gietvormer (molder) specialized in creating molds used for casting ceramic pieces. This process involves designing and fabricating molds, often from plaster, into which liquid clay (slip) is poured. Once the slip sets, the mold is removed, leaving a clay form that can be further processed. Mold making is particularly advantageous for producing complex shapes or replicating intricate designs that would be challenging to achieve through wheel throwing. It also allows for the efficient mass production of uniform items, ensuring consistency across multiple pieces.

Drying (Drogen)

Drying (Drogen) is a crucial stage in the production of Delftware, ensuring that shaped items are properly prepared for the first firing. After the clay is formed into its desired shape, the objects are placed in dryinglofts (droogzolders), spaces specifically designed to facilitate the slow and even removal of moisture from the clay. These lofts were often located in well-ventilated areas within the pottery workshops to ensure consistent airflow and prevent uneven drying, which could lead to warping or cracking.

Proper drying is essential because residual moisture in the clay can cause items to explode or crack during the firing process, as water vaporizes rapidly at high temperatures. The duration of the drying period depended on the size and complexity of the object, as larger or thicker pieces required more time to dry thoroughly. The drying stage also allowed potters to inspect items for imperfections, which could be corrected before firing.

This methodical preparation illustrates the precision required in Delftware production, where each step contributed to the overall quality and durability of the final product. Drying ensured that the clay body was stable enough to withstand the high temperatures of the kiln, making it a fundamental part of the production process.

First Firing (Biscuitbakken)

First Firing (Biscuitbakken) is a critical stage in the Delftware production process, where the dried pieces undergo their initial firing in the kiln. The responsibility for this step lies with the Kiln Operator (Ovenstoker), a skilled artisan who ensures that the firing process is carried out at precise temperatures, typically ranging between 800 and 1000°C. This first firing transforms the clay objects into biscuit ware, a semi-hardened and porous state that is durable enough for subsequent glazing and decoration.

The biscuit firing process requires careful monitoring of both temperature and timing, as any variation can compromise the structural integrity of the pieces. The kiln operator's expertise is essential in achieving a uniform firing, as uneven heating could result in warping, cracking, or incomplete transformation of the clay. Once fired, the biscuit ware is allowed to cool gradually in the kiln to prevent thermal shock, ensuring that the items are ready for the next stages of production. This firing is a foundational step that sets the stage for the glazing and decorative processes, highlighting the importance of precision and skill in creating high-quality Delftware.

Glazing (Glazuren)

Glazing (Glazuren) is an essential step in Delftware production, where the Glazer (Glazuurder) applies a tin glaze to the biscuit-fired pieces. This tin glaze is composed of a lead-based glaze mixed with tin oxide, which creates a white, opaque coating. The glaze serves as a foundation for decoration, providing a smooth and uniform surface that mimics the appearance of porcelain.

The glazer's work requires precision to ensure an even application, as inconsistent glazing can lead to uneven surfaces or imperfections after firing. The pieces are either dipped into a glaze solution or sprayed with the glaze, depending on the size and shape of the object. Excess glaze is carefully removed to avoid pooling or dripping, which could affect the final appearance.

Once glazed, the pieces are left to dry, allowing the coating to adhere firmly before they undergo the second firing. This step not only enhances the durability and aesthetic quality of the pottery but also prepares the surface for detailed decoration using pigments. The glazing process highlights the technical expertise required in Delftware production, bridging functionality and artistry.

Decoration (Decoratie)

Decoration (Decoratie) is a highly skilled stage in Delftware production, where the Painter (Schilder) meticulously hand-paints designs onto the glazed surface of the biscuit-fired pieces. Using cobalt oxide as the primary pigment, the painter applies intricate patterns, motifs, or scenes directly onto the tin glaze. Upon firing, the cobalt oxide reacts with the glaze, producing the characteristic rich blue color that defines Delft Blauw.

The painter's work requires precision, artistic skill, and efficiency. Designs are often guided by stencils (sponsen), which help transfer patterns onto the pottery, ensuring consistency across pieces while allowing room for individual artistic expression. Typical designs include floral patterns, landscapes, biblical scenes, or Chinoiserie-inspired motifs, catering to both local and international tastes.

A single stencil could be reused multiple times, depending on the quality of the material and the care taken during handling. Parchment stencils were particularly robust, but frequent use and the application of charcoal powder could wear them down over time, requiring replacements. The longevity of a stencil also depended on the complexity of the design, as intricate patterns were more susceptible to damage during repeated use. Frequent application of charcoal powder during the design transfer process could lead to wear and tear, especially in intricate patterns with numerous perforations. Consequently, while a well-maintained stencil could be employed numerous times, the need for periodic replacement was common to maintain the precision and quality of the designs. Although a stencil simplified his task, the quality of the product always depended on the proficiency of the artist.Walter Liedtke, Vermeer and the Delft School (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 193.

The painted pieces are then prepared for a final firing, during which the designs fuse permanently with the glazed surface. This process not only secures the decoration but also enhances its vibrancy and durability, ensuring that the final product meets both aesthetic and functional standards. The role of the painter is central to the artistic identity of Delftware, blending tradition and creativity in each piece.

Glaze Firing (Glazuurbakken)

Glaze Firing (Glazuurbakken) is the final firing stage in Delftware production, where the Kiln Operator (Ovenstoker) carefully oversees the process to fuse the glaze and decoration onto the pottery. This firing occurs at temperatures ranging from 900 to 1100°C, ensuring that the tin glaze melts and adheres seamlessly to the surface of the pieces, locking in the painted designs.

The kiln operator's role is critical in maintaining consistent heat throughout the process, as variations in temperature could cause imperfections, such as discoloration, bubbling, or cracking. The kiln must be gradually heated and cooled to prevent thermal shock, which could damage the pottery. The result is a smooth, glossy surface that enhances the cobalt blue decoration while providing durability and a porcelain-like finish.

This stage not only solidifies the artistic elements of Delftware but also transforms the pieces into their final, functional forms. The glaze firing is the culmination of the meticulous craftsmanship and teamwork involved in Delftware production, ensuring that each item meets the high standards for which Delft pottery is renowned.

| Aspect | Kraak Porcelain | Delftware |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Porcelain made from kaolin clay, feldspar, and silica | Tin-glazed earthenware, made from local clays and marl |

| Appearance | Translucent, brilliant white with smooth, vitrified surface | Opaque, slightly less refined white surface due to glaze |

| Durability | Extremely durable; resistant to heat and liquids | Durable but prone to chipping, exposing reddish earthenware |

| Decoration | Intricate underglaze blue designs, featuring floral motifs, birds, and landscapes | Imitative blue designs using cobalt oxide; adapted with Dutch themes like tulips and windmills |

| Production Complexity | High: Required advanced kilns and specialized labor | Medium: Less complex processes but required skilled glazing and firing |

| Cost | Expensive: Imported luxury good with high shipping costs | Affordable: Locally made; cheaper materials and processes |

| Availability | Limited supply, especially during Ming dynasty decline | Widely available due to domestic production in the Netherlands |

| Cultural Appeal | Exotic and luxurious, symbolizing wealth and refinement | Familiar and adaptable; incorporated local and European motifs |

| Impact on Market | Preferred by the elite and used as a status symbol | Accessible to middle-class households, increasing popularity |

There were three reasons why most Delft Blue pottery was white and blue. Delft Blue was an alternative to Chinese porcelain, and Chinese porcelain was also white and blue. The use of blue was much easier in the production process than red. White and blue Delftware was much more affordable than white and red pottery.Pim Tijburg, "Delft Blue Pottery: The 10 Most Asked Questions & Answers," Accessed February 27, 2024, https://netherlandsinsiders.com/delft-blue-pottery-the-10-most-asked-questions-answers/?.

In 1640, Delft housed eleven pottery factories, each employing an average of fifteen painters and assistants. By 1670, this number had grown to twenty-eight factories, with approximately sixty employees per factory. The peak of Delftware production occurred in the late seventeenth century, around 1670, when the industry became the most significant employer in Delft.

Invention

Anonymous, Delft

c. 1660–1675

Tin-glazed earthenware (faience), h. 8.5 x l. 15.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Under the influene of Chinese Kraak, virtually all Delftware (more than 90%) was white and blue, but over time they expanded their palette to create polychrome wares that catered to European tastes, although they were generally less popular. These multicolored designs reflected Dutch artistic traditions, incorporating motifs such as tulips, windmills, and biblical themes. The range of colors and their skilled application underscored the craftsmanship and adaptability of Delftware artisans, allowing their products to gain prominence in both domestic and international markets.

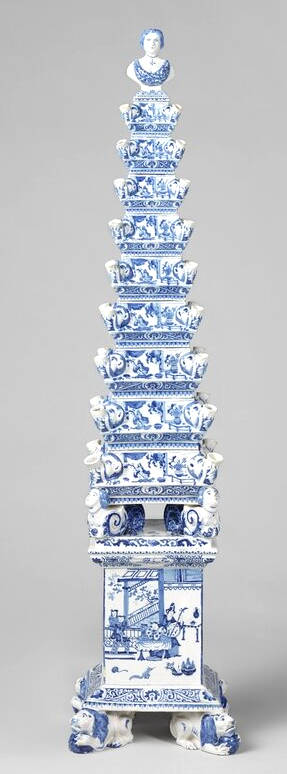

Moreover, Delft artisans expanded far beyond the production of traditional tableware, exploring new styles, objects, and decorative techniques with remarkable creativity and adaptability. One prominent area of innovation was the creation of decorative objects such as tiles, plaques, and sculptural pieces. Delft tiles, often adorned with biblical scenes, landscapes, and patterns, became a staple in Dutch homes, used to decorate walls, fireplaces, and even floors. Plaques and large panels were also crafted, featuring intricate designs inspired by Dutch paintings and prints. Sculptural items, including miniature figurines, animals, and whimsical objects like shoes, teapots, and flower bricks, added a playful yet artistic dimension to their repertoire (fig. 4 & 5).

Attributed to De Metaale Pot (Lambertus van Eenhoorn), Delft

c. 1692–1700 (segments and top made by Tichelaar, Makkum, 2004)

Tin-glazed earthenware (faience), h. 156 x W. 38 x d. 38 cm; weight 29 kg

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Beyond these decorative pieces, Delft artisans contributed significantly to architectural ceramics, producing tiles and other elements that became integral to Dutch interior and exterior design. They also demonstrated their ingenuity by imitating foreign goods, particularly Chinese and Japanese porcelain, which influenced the creation of Delft's iconic blue-and-white ware. They adapted Asian motifs to suit European tastes and even invented new forms like the wide-rimmed klapmutsen bowls, specifically designed for Dutch dining customs.

Functional innovations further showcased their creativity. The multi-spouted tulip vases, designed to display individual tulips during the height of Tulip Mania, combined practicality with ornamental artistry. Apothecary jars, another example, were both decorative and essential for pharmacies and households. Polychrome decorations also marked a significant departure from early blue-and-white designs, as Delft artisans incorporated vibrant colors like green, yellow, and manganese, drawing inspiration from Italian maiolica and French faience.

Delft potters often collaborated with prominent artists of the time, incorporating designs inspired by paintings and engravings. Scenes by artists such as Nicolaes Berchem and Leonaert Bramer were adapted to Delftware, blending fine art with pottery. These innovations allowed Delft artisans to cater to both practical needs and artistic trends, ensuring that their work resonated deeply within the material culture of the Dutch Golden Age and continues to captivate audiences today.

Dutch Women in the Delftware Trade"Leading Ladies," Aronson Delftware, accessed November 28, 2024, https://www.aronson.com/leading-ladies/.

The participation of Dutch women in the Delftware pottery industry during the 17th and 18th centuries was shaped by societal norms, economic necessity, and supportive guild structures. Dutch women had greater economic freedoms compared to their European counterparts, and this extended to the pottery industry, where many assumed roles as co-owners, shopkeepers, and independent entrepreneurs. Their involvement was often linked to the absence of male counterparts, such as during times of war or following the death of a spouse, prompting widows to manage pottery businesses to sustain their households.

Women often entered the trade through partnerships with their husbands, managing in-home shops and contributing to the economic success of their businesses. Guild regulations, while generally restrictive, made exceptions for widows, allowing them to bypass master potter tests to maintain ownership and management. This leniency ensured economic stability for families and safeguarded guild assets. Research has identified numerous women who played critical roles in running Delftware factories, with some achieving high levels of craftsmanship and innovation, such as Barbara Rotteveel and Johanna van der Heul.

Though details of the daily business operations of female entrepreneurs in the Delft pottery industry remain limited, historical records offer valuable insights into their significant contributions. Research reveals that fifty-six women held roles as active owners, co-owners, managers, and co-managers during the seventeenth century, with five achieving the prestigious title of winkelhoudster (shopkeeper). This designation, requiring passage of the Saint Luke’s Guild test for master potter, underscored their professional expertise and independence in a male-dominated industry.

One prominent example is Barbara Rotteveel, who, after becoming a widow, passed the master potters test in 1671 and managed De Drie Klokken (The Three Bells) factory for an impressive thrity-six years. Although the factory was purchased on her behalf by her brother-in-law, Joris Mesch, her long tenure demonstrated her capability and determination. Her leadership exemplifies the resilience of women who navigated societal constraints to establish themselves as respected figures in the industry.

Cornelia van Schoonhoven and her sisters also highlight the entrepreneurial spirit of women in Delft. Cornelia partnered in De Porceleyne Clauw (The Porcelain Claw) but took full control after her initial partner mismanaged the business. Following her death in 1670, her sisters Maria and Elisabeth successfully continued the enterprise for decades, showcasing the strength of familial collaboration in sustaining female-led businesses.

Another notable figure, Elisabeth Jansdr. Klinck, managed De Drie Porceleyne Flessies (The Three Porcelain Bottles) while her husband was abroad. She passed the master potters test herself, a significant achievement, as her male co-owners did not. Her role as shopkeeper and manager between 1671 and 1675 illustrates the critical roles women played in ensuring the continuity and success of Delft pottery factories, often defying the gender norms of their time.

Johanna van der Heul, widow of Pieter Adriaensz. Kocx, stands out as one of the most influential female figures in the Delftware industry. Following her husband’s death in 1703, she managed their pottery factory, De Grieksche A (The Greek A), for nearly two decades before selling it in 1722. A skilled pottery maker in her own right, van der Heul played a hands-on role in the design and production of Delftware models. Known for her preference for animal figures, she left her mark on the industry with pieces bearing her initials, JVDH, although she frequently continued using her late husband’s brand, PAK, as evidenced by a dated dish from 1713.

Van der Heul’s tenure was characterized by innovation and technical expertise. She successfully advanced techniques pioneered by earlier craftsmen, such as polychrome decoration achieved through the mixed-fire method. Her ability to balance tradition with innovation not only preserved the reputation of her factory but also contributed to the broader development of Delftware during her era. Van der Heul's legacy highlights the vital role women played in shaping the artistic and technical achievements of the Delft pottery industry.

Guild of Saint LukeDelfts Aardewerk, "Potters in the Guild of Saint Luke: Organisation & Trade," July 17, 2019, https://delftsaardewerk.nl/en/learn/3577-potters-in-the-guild-of-saint-luke?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed November 29, 2024).

In Delft, producers of tin-glazed earthenware belonged to the Guild of St Luke, which also represented painters, glass makers and sellers, embroiderers, sculptors, booksellers and art dealers. From 1661 porceleynbackers (faience producers) and sellers became official members of the guild.

Initially, fine artists such as painters and sculptors held a more prestigious status within the Delft Guild of Saint Luke compared to Delftware producers. However, as the Delftware industry expanded and gained economic significance, the standing of its producers within the guild improved. By 1648, faience producers were included among the guild's hoofdmannen, or headmen, reflecting their elevated position.

Despite this advancement, tensions arose due to differing artistic priorities and economic interests between fine artists and Delftware producers. In 1678, Delftware producers sought to establish a separate guild to better represent their specific concerns. Although this request was denied, a compromise was reached in 1689 with the appointment of a separate directorate of three faience producers to advocate for the Delftware industry within the existing guild structure.

Distribution

Leonaert Bramer

17th century

Collection Special Collections Leiden University

During the seventeenth century, Delftware was widely distributed both domestically and internationally. In the Netherlands, it was sold in local markets and specialized shops. Internationally, Delftware reached markets in France, Spain, England, and the East Indies, facilitated by the extensive trade networks of the VOC.

"While much is known about the production of Delftware, its distribution has raised intriguing questions. Delftware was often sold directly from factories, where owners lived in buildings with a storefront facing the street and the factory located at the back. These homes typically included a designated winkelkamer (shoproom), identified in inventories by counters and shelving used to display Delftware. In addition to factory shops, independent ceramics retailers in Delft sold a variety of wares, including Delftware, Asian porcelain, and English creamware. Notably, English wares competed directly with Delftware, and even Delft potters were known to use English ceramics in their households, as documented in Den Opkomst,Bloei,Verval en tegenwoordigen Toestand der Stad Delft,in derzelver Fabryken en Trafykenby R. Bakker in 1800.

"Delftware was also distributed at weekly markets and annual fairs, such as the kermis, which could last up to three weeks (fig. 6). An exportation document from 1691 highlights the significance of these events, noting that twenty-two out of eighty-six cargoes were labeled as kermisgoed. However, competition at these markets from other porcelain and earthenware producers posed a challenge to Delft's industry. To safeguard its market, Delft enacted regulations banning door-to-door sales and the sale of goods from carts, ships, or barks, although repeated renewals of these bans indicate frequent violations. A drawing by Leonard Bramer, a Delft artist known for his Delftware illustrations, depicts a street vendor selling earthenware from wicker baskets, illustrating the persistence of informal trade despite the city's efforts to control it."

Willem Pietersz. Buytewech Willem Pietersz. Buytewech

c. 1617–1622

Pen on paper, 27.3 x 39.8 cm

Fondation Custodia, Paris

However, Delft pottery industry mainly found its market outside of Delft, in cities such as Gouda, Rotterdam and Amsterdam, but also to Hamburg, Bremen and Ghent."The Importance of Waterways. Shipping Delftware in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries," Aronson Delftware, accessed November 28, 2024, https://www.aronson.com/the-importance-of-waterways/. Delftware was regularly shipped to these cities as merchants and retailers placed their orders directly with the Delft factories. Every week, ships would travel between Delft, Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Gouda to collect and transport the earthenware goods."The Importance of Waterways. Shipping Delftware in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries," Aronson Delftware, accessed November 28, 2024, https://www.aronson.com/the-importance-of-waterways/. In 1699, three boxes of Delftware were shipped from an Amsterdam merchant to Boston, USA."The Distribution of Dutch Delftware," Aronson Delftware, accessed November 28, 2024, https://www.aronson.com/the-distribution-dutch-delftware/.

"The transportation of Delftware in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries involved complex logistics and frequent challenges. Delftware objects were packed in crates or baskets, cushioned with hay or waste, and loaded onto ships. Despite efforts to secure the items, damage sometimes occurred during transit, leading to disputes between potters and merchants over liability. Potters often issued statements asserting that their products were securely packed, which could serve as evidence in their defense, and in some cases, agreements were made between potters and ship captains to minimize conflict. Raw materials for Delftware production, such as clay soil from Tournai, were also transported by ship. Flemish skippers from Ghent played a significant role in this supply chain, delivering clay to Delft and returning with city waste and small batches of Delftware for further trade. These practices, however, created tension with Dutch skippers, ultimately leading to the ban of Ghent skippers in 1751, although exceptions were made to ensure the continued supply of essential materials to Delft. The transport of Delftware within the Netherlands, particularly to Amsterdam, was also fraught with issues. Amsterdam's small-skippers' guild often transported goods from Delft, but complaints arose when skippers were unavailable, lacked space, or had already departed with other cargo. In 1688, a solution was introduced with the appointment of a Delft skipper to manage small loads, whose faster and more flexible service gained the trust of both Delft potters and Amsterdam merchants. By the mid-eighteenth century, this Delft skipper had become the preferred transporter for many, exemplified by the case of merchant Johannes Bijnima in 1760, who specifically requested a dedicated earthenware skipper for deliveries from the De Romeyn factory.""The Importance of Waterways: Shipping Delftware in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries," Aronson Delftware, accessed November 28, 2024, https://www.aronson.com/the-importance-of-waterways/.

Reinier Nooms

1652–1654

Print, 13.4 x 24.4 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

B

- Banding Wheel: A manually operated, rotating platform used by potters to decorate or shape ceramic pieces uniformly. It allows for precise control when applying decorations or trimming.

- Bisque: Unglazed ceramic ware that has undergone bisque firing. It is porous and ready to accept glaze applications.

- Biscuit firing: The initial firing of unglazed earthenware, which produces biscuit wares.

- Body: Fired clay with no glaze or enameling.

C

- Casting Slip: A liquid mixture of clay and water with added deflocculants used in slip casting to form ceramic objects in plaster molds.

- Chamotte clay: Pre-fired clay that is added to raw clay used to make pots to produce a stronger body.

- Charger: Chargers have a diameter of 26 centimeters or more. Smaller versions are generally referred to as plates.

- China Clay: Another term for kaolin, the primary clay used in porcelain production due to its purity and whiteness.

- Chinoiserie: The use of motifs derived from Chinese art to give objects made in Western Europe an "exotic" appearance. The Delft pottery industry was instrumental in establishing this fashion.

- Craquelure (crackle): Hairline cracks in the glaze caused during glaze firing as the glaze and body shrink at different rates.

- Creamware: A hard type of earthenware with a cream-colored body covered with a transparent lead glaze.

- Crystalline glaze: Glaze with small crystals on the surface formed as a result of gradual cooling of metal oxides in the glaze.

D

- Delftware: English term for tin-glazed earthenware, referencing the Dutch town of Delft. Capitalized, it refers specifically to Delft earthenware; lowercase refers to tin-glazed earthenware made anywhere.

E

- Earthenware: A type of ceramic with a porous body, created at firing temperatures of approximately 800–1150°C. Must be glazed to be watertight.

- Eggshell porcelain: Porcelain with extremely thin walls, often translucent, resembling eggshells.

- Enamel: Vitreous pigment (either opaque or transparent) that is coloured with metal oxides applied to the surface of ceramics, typically as overglaze decoration requiring a lower-temperature firing.

F

- Factory mark: A mark referring to the pottery, usually referencing the name of the pottery or its proprietor or manager.

- Faience: Tin-glazed earthenware, often with a thin body and smooth front surface.

- Familles: Enamelled Chinese porcelain is traditionally divided into different colour families (‘famille’ being French for family): vert (green), rose (pink), noir (black) and jaune (yellow). These categories were defined in Europe in the 19th century.

- Feldspar: A group of minerals used in ceramic bodies and glazes as a flux to lower the melting point.

- Firing;The entire process of heating and cooling off pottery in the kiln. There were usually two firings: the biscuit firing and the glaze or glost firing.

- Flatware: Collective term for flat items like plates and platters, to distinguish them from hollow wares. >

- Flux: A material that promotes melting or fusion in glazes and clay bodies by lowering the melting point of silica.

- Foot Ring: The circular base of a ceramic piece, often left unglazed to prevent it from fusing to kiln shelves during firing.

G

- Glaze: Vitreous layer on the surface of ceramics.

- Glaze or Glost Firing: The second firing, designed to fuse the glaze to the surface at a temperature of approx. 1000° C. To prevent objects from fusing together in the kiln, they are separated using spurs or pegs and saggars.

- Grand feu technique: The process of firing objects at approximately 1000°C, often during the second (glaze or glost) firing.

I

- Imari porcelain: Type of Japanese porcelain whose decorative style, named after the port of Imari, was imitated in (a.o. China and also) Delft. The blue, red and gold porcelain first appeared on the Dutch market around 1680.

K

- Kakiemon porcelain: Type of Japanese porcelain whose decorative style was imitated in Delft, among other places. The multicoloured porcelain with refined decoration (named after a family of potters) first appeared on the Dutch market around 1680.

- Kangxi porcelain: Type of Chinese porcelain developed during the Kangxi period in the Qing dynasty (1662-1722).

- Kaolin or China clay: A type of clay essential for porcelain production.

- Kendi: Jug with a round body. The neck or spout sits on the rounded shoulder. Some are in the shape of animals (including elephants, ducks and fish). Kendi were used throughout Southeast Asia and the Middle East. A porcelain version of this form was introduced to the Netherlands in the early 17th century.

- Kraak ware or Kraak porcelain (see Wanli porcelain): A type of Chinese porcelain made in the time of Emperor Wanli (1573-1619) and his successors, right through to the fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644. The distinctive blue decoration is divided into panels and applied on a white ground.

- Kwaarten: Traditional Dutch term for the application of a top layer of transparent lead glaze (kwaart) to produce a brilliantly shiny surface. Also known as coperta.

L

- Lead glaze: A transparent glaze whose main component is lead oxide.

- Leather-hard: The stage of clay dryness where it is firm yet still retains moisture, allowing for carving, joining, and trimming without distortion.

- Lustre glaze: Glaze with a metallic shine, obtained by the addition of metal oxides.

M

- Majolica: Tin-glazed earthenware with a layer of tin glaze on the front and transparent lead glaze on the back.

- Maker’s mark: A mark used by a craftsman to show the workshop where objects were made.

- Marl: Adding earth from Tournai (known in Dutch as Doornikse aarde) to clay produced a pale yellow body.

- Molding: Forming ceramic pieces by pressing clay into a rigid mold, allowing for the production of uniform shapes.

- Monochrome: Decoration in a single colour. In Delft usually blue.

- Muffle kiln: Small kiln used to fire smaller batches of pots. Some gilders had kilns of this type on the premises, presumably to fire gilded pieces using the petit feu technique. Hence the Dutch term ‘goudschilderoven’ (= gilder’s kiln).

O

- On-glaze: Decorative enamels applied over the glaze layer and fired at low temperatures to fuse the decoration without affecting the underlying glaze.

- Oxidation firing: Allowing oxygen in during the glaze firing so that clay containing iron oxide, for example, turns red.

P

- Pâte-sur-pâte: Decoration produced on porcelain using semi-liquid white porcelain slip, sometimes tinted with metal oxides.

- Petit feu technique; The process of firing objects at a temperature of approx. 600° C. This was usually done in small muffle kilns, known in Dutch as goudschilderovens (= gilders’ kilns), used for gilded objects and delicate colours that would be incinerated at higher temperatures.

- Plate: Plates have a diameter of up to 26 centimeters. Larger plates can also be referred to as platters.

- Plateel:Contenporary term for lead- and tin-glazed earthenware (majolica and faience). Also used to reference typical wares produced in the Netherlands in the early twentieth century.

- Plateelbakker: Dutch term meaning a producer of lead- and tin-glazed earthenware (majolica and faience).

- Plateelbakkerij: Dutch term for a pottery producing lead- and tin-glazed earthenware (majolica and faience).

- Plateelschilder: Dutch term for a painter specially trained to decorate earthenware.

- Polychrome: Decoration in more than one colour.

- Porcelain: Type of ceramic with a hard, non-porous body created by firing at a temperature of 1300-1500 ºC.

- Porceleyn (Porceleyne, porcellyne etc.): The old name used in Delft for tin-glazed earthenware that was meant to imitate porcelain.

- Pounce: Paper on which the outlines of a decorative design have been pricked out. The design is transferred to the object through the holes using powdered charcoal.

- Porcelain: A type of ceramic with a hard, non-porous body, fired at temperatures of 1300–1500°C.

R

- Reduction firing: A technique whereby the amount of oxygen entering the kiln during glaze firing (at a relatively high temperature) is reduced in order to produce colour variations and textured effects in the glaze.

- Running glaze: Glaze with a low melting point that runs when fired. Running glazes are applied on top of a glaze with a higher melting point.

S

- Saggar: A cylindrical earthenware container in which earthenware objects would be stacked for firing. To prevent the objects from fusing to the surface, each one would rest on triangular pegs inserted through the wall of the saggar. To protect the pots from kiln fumes, the saggar was closed during firing by placing tiles on top and underneath.

- Sgrafitto: Technique whereby decoration is incised into the surface of a ceramic object that is covered with a layer of slip (engobe).

- Shrinkage: The reduction in size of a clay body during drying and firing due to loss of water and densification of particles.

- Sinter engobe: A blend of engobe and a vitreous substance that produces a glaze-like shine on a ceramic object.

- Slip: Liquid clay used as an adhesive to stick together the different parts of an object during the production process.

- Slip Casting: Forming ceramic objects by pouring slip into a plaster mold, which absorbs water and forms a solid layer against the mold walls.

- Spur: Ceramic support used to separate pieces of majolica in the kiln during glaze firing and stop the pieces fusing together.

- Spur mark: Scar on the front of a piece of majolica caused by the spur used to support it in the kiln.

- Stoneware: Hard, non-porous ceramic fired at approximately 1200–1300°C.

T

- Thrower: A craftsman who makes objects on a potter’s wheel.

- Throwing: The process of shaping clay on a potter's wheel by hand while it spins, allowing for symmetrical forms. Tin glaze bath: Tub containing tin glaze into which the wares (biscuit) are dipped after the first firing, creating a white surface to which the painter can then apply the decoration.

- Transfer printing: Technique whereby a design printed on prepared paper is transferred to the surface of a ceramic object.

- Transitional porcelain: Blue-and-white Chinese porcelain produced in the period of transition between the Ming and Qing dynasties (during the reign of Emperor Shunzhi between 1644 and 1661). Its decoration is characterised by continuous narrative scenes.

- Translucency: The property of allowing light to pass diffusely through a material; in porcelain, it is a valued aesthetic quality.

- Throwing: The process of shaping clay on a potter's wheel by hand while it spins, allowing for symmetrical forms.

W

- Wanli porcelain: A type of Chinese porcelain from the time of Emperor Wanli (1573–1619), characterized by distinctive blue decoration.

- Wheel: A potter's wheel, a device that spins clay to facilitate the shaping of symmetrical ceramic forms.

X

- XRF: Research technology based on x-ray fluorescence used to measure the composition of materials, increasingly in studies of Delftware.

Bibliography

- Bang, Byung Sun. "Influence of Chinese Export Porcelain on Delftware during the Dutch Republic Era." Art History Journal 48 (June 15, 2017): 311–35.

- Carswell, John. Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain and Its Impact on the Western World. Exhibition Catalogue. Chicago: David and Alfred Smart Gallery, 1985.

- Caiger-Smith, Alan. Tin-Glaze Pottery in Europe and the Islamic World: The Tradition of 1000 Years in Maiolica, Faience and Delftware. London: Faber and Faber, 1973.

- Crowe, Yolande. Persia and China: Safavid Blue and White Ceramics in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1501–1738. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 2002.

- Hochstrasser, Julie. Still Life and Trade in the Dutch Golden Age. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Howard, David, and John Ayers. China for the West: Chinese Porcelain and Other Decorative Arts for Export, Illustrated from the Mottahedeh Collection. London and New York: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978.

- Jörg, Christiaan J.A. Porcelain from the Vung Tau Wreck: The Hallstrom Excavation. Singapore: Sun Tree Publishing, 2001.

- Kerr, Rosemary. "Early Export Ceramics." In Chinese Export Art and Design, edited by Craig Clunas. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1987.

- Kroes, Jochem. Chinese Armorial Porcelain for the Dutch Market: Chinese Porcelain with Coats of Arms of Dutch Families. Den Haag: Centraal Bureau voor Generalogie and Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, 2007.

- Pluis, Jan. The Dutch Tile: Designs and Names 1570–1930. Nederlands Tegelmuseum – Friends of the Museum of Otterlo Tiles. Leiden: Primavera Pers, 1997.

- Rinaldi, Maura. Kraak Porcelain: A Moment in the History of Trade. London: Bamboo Publishing, 1989.

- Savage, George. Pottery Through the Ages. London: Penguin, 1959.

- Vainker, S.J. Chinese Pottery and Porcelain. London: British Museum Press, 1991.

- Wu, Ruoming. The Origins of Kraak Porcelain in the Late Ming Dynasty. Weinstadt: Verlag Bernhard Albert Greiner, 2014.

- Wuestman, Gerdien. "Wouwerman on Delftware." Rijksmuseum Bulletin57, no. 3 (September15, 2009): 236–43.