The seventeenth century, often hailed as the Dutch Golden Age, was a period of remarkable cultural, economic, and artistic prosperity in the Netherlands. Central to this era was the evolving role of women, both in society and as subjects of artistic representation. Departing from previous centuries in which female figures were predominantly depicted in religious or mythological contexts, Dutch artists began to portray women in everyday life, capturing their domestic duties, social interactions, and individual identities (fig. 1). This shift in artistic focus not only reflected changes in aesthetic preferences but also mirrored broader societal transformations regarding the perception and valuation of women's roles in both the private and public spheres.

Quiringh Gerritsz. van Brekelenkam

1661

Oil on panel, 47 x 36 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Given the divergent viewpoints among contemporary observers, interpretations of the private lives and social interactions of Dutch women in the seventeenth century require cautious scrutiny. Influenced by their unique cultural backgrounds and biases, these observers portrayed Dutch society through subjective lenses. Consequently, accounts—from foreign travelers to local authors—are often colored by personal, social, or religious predispositions, leading to conflicting representations of women's roles, behaviors, and freedoms during this period. Evaluating these sources necessitates careful consideration of the perspectives and motivations that influenced each observer's account.

The historical concept of Golden Age has been recenty called into question. The term "Dutch Golden Age" traditionally refers to the seventeenth century in the Netherlands, a period marked by significant advancements in trade, science, military prowess, and the arts. However, contemporary scholars and institutions have critiqued this characterization, arguing that it overlooks the era's darker aspects, particularly those related to colonialism and slavery.

Colonial Exploitation and Slavery: The prosperity of the Dutch Golden Age was significantly bolstered by colonial enterprises, including the exploitation of colonies and involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. The wealth generated from these activities funded the flourishing arts and sciences of the period. Critics argue that celebrating this era without acknowledging these injustices presents a skewed historical narrative.

Reevaluation by Cultural Institutions: In response to these critiques, some Dutch cultural institutions have reconsidered their portrayal of the seventeenth century. For instance, the Amsterdam Museum decided to stop using the term "Golden Age" to describe this period, aiming to present a more nuanced view that includes the negative aspects of the era, such as colonialism and slavery.

Artistic Representations: Art from the Dutch Golden Age, while celebrated for its technical mastery, has also been scrutinized for its role in reflecting and perpetuating societal norms of the time. Some artworks have been reinterpreted to uncover underlying themes related to colonialism, wealth disparity, and moral questions, prompting discussions about the ethical implications of art patronage and production during this period. These critiques highlight the importance of a comprehensive historical perspective that acknowledges both the achievements and the moral complexities of the Dutch Golden Age.

Demographics

Population and Life Expectancy

Estimates suggest that the population of the Dutch Republic was between 1.5 and 2 million in the mid-seventeenth century. Women made up about half of this population, as would be expected. However, due to the high number of men engaged in maritime-related activities—either as sailors, fishermen, or members of the Dutch East India Company (VOC)—the actual number of women exceeded that of men in some regions. It is estimated that tens of thousands of men were at sea at any given time, contributing to a demographic imbalance that resulted in a slightly greater population of women, particularly in the urban centers of the western maritime provinces (North and South Holland and Zeeland), where women outnumbered men by an unusually high margin.

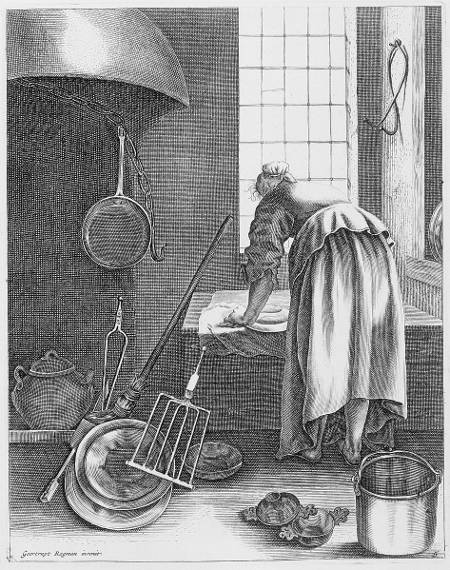

Geertruydt Roghman

c. 1648–1650

Engraving, 21.5 x 17 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gabriel Metsu

c. 1660-1665

Oil on canvas, 32.2 x 27.2 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Life expectancy of Dutch women varied significantly based on class, geographic location, and other factors. For women, the average life span was estimated to be in the mid-40s, though many did not survive into old age due to complications related to childbirth, disease, and other health risks that were poorly understood or managed at the time. Infant mortality was high, with nearly a quarter of infants dying before their first birthday, and childhood diseases claimed many more lives before adulthood. However, if a woman reached her twenties, her likelihood of reaching a much older age improved considerably.

Contrary to the typical "female mortality advantage" The term "female mortality advantage" refers to the observed phenomenon where females, on average, have lower mortality rates and longer life expectancies than males. This means that women tend to live longer than men and are less likely to die at any given age throughout their lifespan. observed in later periods, findings show that Dutch women did not consistently outlive men during periods of economic crises and sometimes even had higher mortality rates. Factors such as increased exposure through caregiving roles, social responsibilities, and limited access to protection and resources may have diminished women's biological advantages. A study by Daniel R. Curtis and Qijun Han suggests that while female agency was noted in the period, it did not necessarily translate to improved survival during severe crises.Daniel R. Curtis and Qijun Han, "The Female Mortality Advantage in the Seventeenth-Century Rural Low Countries," Gender & History 33, no. 1 (2021): 50–74.

Women’s roles as primary caregivers significantly raised their exposure to infectious diseases. When a family member fell ill, the responsibility of care often fell to women, placing them in close contact with infected individuals (fig. 3). Pregnancy and childbirth in the seventeenth century carried substantial health risks, particularly during periods of famine or epidemics. Malaria, for example, which was endemic in some parts of the Low Countries, severely affected pregnant women, increasing their risk of death through complications like anemia and fever. Women were also the primary providers of paid caregiving work, particularly during epidemics. The schrobbers ("scrubbers") (fig. 2) were mostly women hired to clean homes and care for those suffering from infectious diseases such as the plague. Despite the dangerous nature of the job, women continued to take these roles, often out of financial necessity.

Infancy and Childhood

Ferdinand Bol (assumed certain)

Unknown

Oil on canvas, 75.6 x 92 cm.

National Museum, Osloe

In the seventeenth century, infancy was an especially vulnerable period. Medical knowledge was rudimentary, and infectious diseases were common.In 17th-century Europe, infectious diseases were widespread and often deadly, with the bubonic plague, smallpox, and typhus among the most feared. Plague outbreaks—in the Nehterlands 1624–1625, 1635–1637, 1655, 1663–1664—had devastating effects, while smallpox and typhus affected people across all social classes. Diseases like malaria and dysentery thrived in marshy or overcrowded areas, and tuberculosis, or "consumption, " was a chronic respiratory illness causing significant mortality. Measles and influenza also spread rapidly, especially in colder months and urban settings. Poor sanitation, limited medical knowledge, and crowded living conditions made these diseases challenging to control and contributed to high mortality rates. Mothers often breastfed their infants for extended periods (fig. 4), which was believed to improve infant survival rates. Swaddling was widely practiced, and children were kept in tightly wrapped cloth during their early months. In 1636, the renowned Dutch physician Johan van Beverwijck (1594–1647) noted that children in his country were swaddled "from head to foot" because this method "best protected and kept [their] limbs straight.Swaddling in the 17th-century Netherlands was a widely accepted practice, applied to infants from birth until they were roughly a year old. Wrapped tightly in cloth, infants were kept still, both as a means of providing comfort and as a safeguard against injury. The practice was based on beliefs that swaddling replicated the snug environment of the womb, which was thought to calm infants and prevent any abnormal limb growth or bodily deformation. Additionally, swaddling served practical needs in households where mothers balanced work and childcare, as it allowed them to manage infants safely while attending to other responsibilities. However, some critiques emerged during the late 17th century, as changing attitudes toward child-rearing began to question the health effects of swaddling. Concerns included the potential for restricted breathing and possible limitations on natural growth. While traditional views held that swaddling protected infants from drafts and dampness, which were considered to cause illness, physicians and some caregivers began advocating for less restrictive methods that would allow infants more freedom of movement. Dutch genre paintings from the period, often depicting domestic scenes with swaddled infants in cradles, provide a visual record of this cultural norm while hinting at the gradual shift toward a more flexible approach to infant care. The restrictive garments worn by elite children until the age of five or six may have served a similar purpose. Childhood was marked by learning basic skills, often through imitation of adults, and for girls, it involved helping with household tasks from an early age. The iconography of Dutch paintings from the period often depicts young girls taking care of younger children or playing with dolls and miniature furniture or household items, suggesting the significance of such activity in shaping gender expectations.

Adolescence and Gender Roles

Adolescence was generally shorter than we perceive it today, as societal expectations propelled young girls swiftly into adult roles. By the time a girl reached her early teens, she would have been expected to contribute significantly to household labor, particularly in rural areas where agricultural work was demanding. In urban centers, young women might work in family businesses or as servants in wealthier households. The transition from childhood to adulthood was, therefore, a fluid process marked by increased responsibilities rather than a clear-cut rite of passage.

Marriage and Marital Status

Gonzales Coques (attributed)

1662

Oil on canvas, l17.4 x 239 cm.

Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin

Marriage was a significant milestone in a Dutch woman's life (fig. 5). It was seen as indissoluble, making the selection of a partner crucial; couples were ideally from the same class, age group, and religion. The promise of marriage was sacred. If a boy and girl promised each other to get married and one of them declined later on, one could summon the other party, and the Commissioners for Marriage Affairs would make a judgment.

Couples were typically allowed limited freedom to meet and interact, but these meetings often took place in controlled environments, such as family gatherings or public spaces where others could observe. Physical boundaries were maintained, and the display of affection was modest by modern standards. Still, the Dutch Republic’s emphasis on individual choice allowed for a degree of personal agency within these parameters. Families tended to guide rather than dictate relationships, resulting in a courtship model that balanced personal preference with societal expectations.

A typical seventeenth-century Dutch marriage ceremony was relatively modest compared to some other European traditions, reflecting the values of the Protestant Reformation, which emphasized simplicity, especially within the Dutch Reformed Church. Marriage was seen as both a civil and religious event. Civil registration was required before the church ceremony, which took place in the town hall rather than the church sanctuary to avoid associations with Catholic ritual. This civil emphasis underscored the legal and societal role of marriage, as it formally acknowledged the new family unit.

Initially, Dutch couples married in winter, aligning with the agricultural off-season—a pattern seen across much of Europe. However, economic and social factors gradually influenced this preference, particularly in rural areas where May became the preferred month for weddings, aligning with annual employment contracts and symbolizing renewal. This transition emerged first in provinces like Limburg, one of the first to adopt May marriages in the 1670s—likely due to disruptions from military conflicts—and later spread to other regions, reflecting the intricate link between marriage customs and labor cycles in the Netherlands.Willem R. J. Vermeulen and Frans W. A. van Poppel, From Winter Wedding to May Marriage: A Transition in Dutch Marriage Seasonality, accessed November 2, 2024.

The bride’s role in the ceremony was both symbolic and practical. She was often escorted by family or friends and traditionally wore attire in sober colors, though she might incorporate small embellishments or fine lace as a nod to the occasion. During the ceremony, she made vows similar to the groom's, pledging to support the marriage materially and spiritually, though her commitments focused on household management and family care. After the ceremony, the couple would typically join friends and family for a modest celebration. While celebrations varied by social class, they often included a meal and music, with an emphasis on the union’s solemnity rather than ostentatious display.

The bride’s role in the ceremony was both symbolic and practical. She was often escorted by family or friends and traditionally wore attire in sober colors, though she might incorporate small embellishments or fine lace as a nod to the occasion. During the ceremony, she made vows similar to the groom's, pledging to support the marriage materially and spiritually, though her commitments focused on household management and family care. After the ceremony, the couple would typically join friends and family for a modest celebration. While celebrations varied by social class, they often included a meal and music, with an emphasis on the union's solemnity rather than ostentatious display.

While Dutch parents generally permitted their children to choose their spouses, marriages were sometimes arranged to secure family business or financial interests, formalized through strict marriage contracts. These contracts often contained detailed provisions to protect individual assets. For instance, when Sara Hinlopen (1660–1749) (fig. 6), widow of WIC director Albert Geelvinck (1647– 1693), remarried Jacob Henricksz. Bicker (1642–1713) in 1695, their agreement carefully separated their wealth, stipulating inheritance solely for blood relatives in the event of divorce or death. If Bicker predeceased her, a portion of his wealth would serve as her new dowry, while if she died first, her wedding jewelry worth 6,000 guilders would revert to him or his heirs.

Gabriel Metsu

1661

Oil on canvas, 77.5 x 81.3 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Typically, dowries became shared marital property; however, a widow could reclaim her dowry and retain any possessions acquired during the marriage. Wedding gifts, legally considered her personal property, were immune from children's inheritance claims. Additionally, if a woman could demonstrate that her husband was mismanaging finances, she had legal grounds to claim her share and protect her assets independently.

Middle-class dowries in early modern Europe typically included a mix of cash, property, movable goods, and personal valuables. Cash was often the primary component, supplemented by bonds or other financial instruments that provided the couple with immediate liquidity and a foundation for household expenses or investments. In many cases, property such as land, houses, or business shares was also part of the dowry, offering both income potential and a stake in family business interests, depending on the bride's family's wealth.

In addition to financial and real estate assets, dowries commonly contained household goods and personal valuables. Essential furnishings, linens, and kitchenware allowed the new household to be fully equipped from the start, symbolizing the family's support for the bride's transition to married life. Jewelry and heirloom items added personal wealth and provided the bride with assets she could retain independently. This structured approach to dowries not only ensured practical support for the marriage but also protected the bride's financial interests, as marriage contracts often allowed her to reclaim portions of her dowry under certain conditions, such as widowhood or a husband's financial mismanagement.

The average age of marriage for women in the seventeenth century was relatively high compared to other parts of Europe, typically ranging from 23 to 27 years old, which normally led to an extended period of supervised courtship lasting several years, often until the prospective bride was in her early twenties—considered an ideal age for marriage. This period allowed young people to transition from adolescence to adulthood while providing ample time for families to evaluate the suitability of potential matches. The life expectancy of the couple was about another 24 years, making it unlikely they ever saw their grandchildren. Half of the brides and grooms had lost their father, mother, or both by the time of their marriage.

Men were expected to demonstrate their reliability, social standing, and suitability as potential husbands, often through gifts or acts of service. Women, on the other hand, were expected to take a more passive role in courtship, emphasizing virtues like chastity, modesty, patience, and obedience. Women rarely made overt advances, as this was considered inappropriate for their gender. In some cases, parental control over relationships was pervasive, often influencing or even obstructing young love, as illustrated by Dutch poet Jan Janszoon Starter (c. 1593–1626),Jan Janszoon Starter was born in Amsterdam and became a prolific writer, whose poems were set to melody in his lifetime. He died young in battle. Many of his poems became the subject of other artworks such as plays or paintings. He is best known for his poem about the M"ennonite Sister." who described a suitor's misery not only due to the woma's coolness but also because of her parents' disapproval.

Although a high proportion of women married, a notable number remained single. Urban areas, in particular, had larger populations of unmarried women who worked in various trades or domestic service. Unlike housewives in many other European countries, who sent servants to do the shopping, Dutch women considered this task an essential part of their domestic duties.

While women in the Netherlands enjoyed relatively liberal rights, authors like Jacob Cats (1577–1660), one of the most influential poets and moralists of the Dutch Golden Age—often referred to as "Vader Cats" (Father Cats) for his influence on Dutch culture—emphasized ideals of feminine passivity, urging young women to remain silent and reserved to maintain propriety. Cats argued that women should avoid appearing eager for marriage and instead act aloof, keeping suitors at a distance. Conduct literature also stressed proper behavior, advocating for upright posture and slow, measured movement as signs of moral character.

Widowhood

Widowhood was also common due to the high mortality rate of men involved in maritime and military activities.The average lifespan for Dutch men in the 17th century was relatively low by modern standards, typically around 40–50 years. However, this figure is somewhat misleading due to high rates of infant mortality; those who survived childhood often lived into their 60s or beyond. Mortality rates were influenced by various factors, including limited medical knowledge, the prevalence of infectious diseases, malnutrition, and periodic warfare. Among adult men, those engaged in certain professions, like seafaring or soldiering, faced additional risks that could further reduce life expectancy. Widows often took on the role of head of the household and managed businesses or family affairs, which provided them with a degree of autonomy that was less common in other parts of Europe.

Many Dutch women remarried, particularly widows. Remarriage was often a practical choice, especially for financial security or to provide stability for any children from a previous marriage. Widows with young children were more likely to remarry, as it helped to ensure support and assistance in managing the household. Social norms generally supported remarriage, especially if the widow was still of childbearing age.

Health and Aging

Nicolaes Maes

ca. 1656

Oil on canvas, 134 x 113 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Old age, for those who reached it, was generally considered to begin in on's fifties. Older women often played essential roles within their families, particularly in caring for grandchildren and maintaining household traditions (fig. 7). The concept of retirement did not exist as it does today; instead, older women continued working in some capacity for as long as their health allowed.

Religion played an important role in the lives of elderly Dutch women, with many becoming more deeply involved in church activities and charity work as they aged. Protestant values, particularly in the Reformed Church, encouraged the elderly to contribute to the moral fabric of society.

Religion played an important role in the lives of elderly Dutch women, with many becoming more deeply involved in church activities and charity work as they aged. Protestant values, particularly in the Reformed Church, encouraged the elderly to contribute to the moral fabric of society.

Prostitution

Prostitution in the seventeenth-century Netherlands was a prevalent and organized aspect of urban life, especially in major cities such as Amsterdam. Legal records, particularly judicial archives, provide detailed accounts of the people involved and societal attitudes toward prostitution during this period. These records reveal the complex intersections of social, economic, and cultural factors that shaped the practice.

Prostitution was technically illegal, but enforcement varied widely depending on local circumstances. Cities like Amsterdam regulated the trade through legal and judicial means, aiming to control public morality while acknowledging its existence. Brothels, known as speelhuizen (playhouses), operated in specific areas, often under the oversight of local authorities. Arrests and prosecutions were usually driven by breaches of public order or concerns about spreading immorality.

The legal system kept meticulous records, particularly in Amsterdam, where the Confessieboeken der Gevangenen (Books of the Confessions of Prisoners) provide an invaluable source of information. These documents include interrogations of individuals accused of prostitution and related activities, offering insights into the lives of both prostitutes and brothel-keepers. Such records are unique in their detail and scope, capturing personal data such as names, ages, places of origin, and professions.

Demographics and Background

Most women involved in prostitution were from the lower socioeconomic strata of urban society. Many came from outside the cities where they worked. For example, in Amsterdam, only 20% of convicted prostitutes were native to the city, with others originating from the Dutch Republic's provinces, Germany, or Scandinavia. These women were typically young, with an average age of 23, though both younger and older individuals were recorded.

Contrary to stereotypes, prostitutes were not predominantly naïve rural servant girls lured to the city. Instead, many had prior experience in low-paid urban trades such as sewing, lace-making, spinning, or peddling. Some worked in service roles that overlapped with the hospitality industry, such as serving in inns or brothels, which facilitated their entry into prostitution.

Public Perception and Representation

Prostitution occupied a dual space in Dutch society, being both a visible reality and a subject of artistic and literary representation. In art, particularly genre paintings, brothel scenes often portrayed women as alluring and elegant, contributing to an idealized image. In contrast, written accounts from contemporaries like Bernard Mandeville offer a less flattering view, describing prostitutes as poorly educated, coarse, and marked by physical signs of manual labor. These discrepancies highlight the gap between artistic conventions and social realities.

Efforts to control the public image of prostitution included statutes regulating clothing. Laws prohibited lower-class women, including prostitutes, from wearing expensive fabrics, lace, or gold, as such attire was seen as morally corrupting and socially disruptive. Despite these restrictions, court records indicate that many prostitutes adopted upper-class fashions, often wearing secondhand gowns, elaborate headdresses, and makeup.

Judicial and Penal Practices

The judicial system played a central role in monitoring prostitution. Convicted women were often sentenced to institutions such as the Spin House, a corrective facility where they were required to work. In some cases, these women were displayed in their flamboyant attire as a moral lesson for the public. Authorities also confiscated luxury items, emphasizing the moral and social transgressions associated with their trade.

In sum, prostitution in the seventeenth-century Netherlands was shaped by a combination of economic necessity, urban migration, and societal regulation. While it was officially condemned, it remained an ingrained part of urban life, reflecting broader tensions between social norms, economic realities, and cultural expressions.