Valuation of Womanhood in a New Society

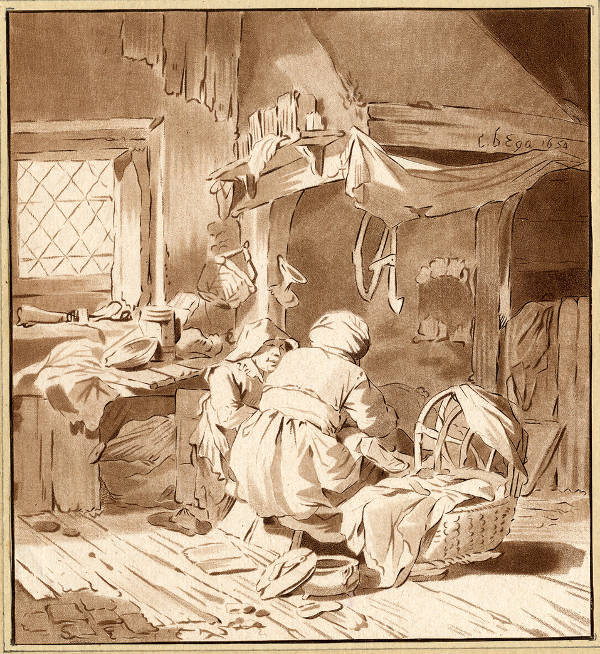

The Dutch Republic, shaped by the principles of the Protestant Reformation, placed a high value on womanhood and the work performed at home. As one of the first modern democracies, the Dutch understood the importance of an educated populace for the functioning of a healthy state. Mothers were entrusted with the crucial responsibility of raising and educating their children in both civil and religious matters (fig. 1). This emphasis on maternal influence acknowledged the foundational role women played in cultivating the virtues and knowledge essential for the Republic's prosperity.

The Dutch Republic, shaped by the principles of the Protestant Reformation, placed a high value on womanhood and the work performed at home. As one of the first modern democracies, the Dutch understood the importance of an educated populace for the functioning of a healthy state. Mothers were entrusted with the crucial responsibility of raising and educating their children in both civil and religious matters. This emphasis on maternal influence acknowledged the foundational role women played in cultivating the virtues and knowledge essential for the Republic's prosperity.

Cornelis Pietersz. Bega

c. 1654

Pen And Ink And Brush Over Pencil On Paper

Private collection

Jan Olis

1640

Oil on panel, 25.7 x 20.5 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

Dr. Johan van Beverwijck (1594–1647), portrayed in Olis's Portrait of Johan van Beverwijck in his Study (fig. 2), was a prominent physician and writer of the time who articulated this appreciation in his treatise Van de Wtnementheyt des Vrouwelicken Geslachts (On the Excellence of the Female Sex; Dordrecht, 1632). He extolled the virtues of Dutch housewives, emphasizing that a solid home foundation was as vital to the state as any other institution. Van Beverwijck argued that the diligent and principled upbringing provided by mothers was indispensable for the nation's well-being.

In the tradition of Erasmus and Vives, Van Beverwijck emphasized both women's intellectual abilities and their moral education, but primarily focused on their physical attributes, suggesting a connection between a woman's external beauty and the nobility of her soul. Drawing on Platonic and Neo-Platonic traditions, including Petrarch and Ficino, Van Beverwijck celebrated feminine beauty as an inspirational force that should be appreciated in a chaste and distanced manner. This view resonated with Petrarchan poetry, where feminine beauty was often depicted as a symbol of both physical and spiritual perfection. Dutch poets like P. C. Hooft followed this convention, linking the beloved's physical beauty—her golden hair, white skin, and blushing cheeks—with the purity and nobility of her soul, thereby transforming romantic admiration into something chaste and honorable.

Foreign Points of View

John Hayls

1666

Oil on canvas, 75.6 x 62.9 cm.

National Portrait Gallery, London

Foreign visitors to the Netherlands were surprised, delighted, and disturbed by Dutch women. Opinions were often contradictory. Joseph Shaw (birth and death dates unknown), an Englishman who traveled through the Netherlands, greatly admired the freedom enjoyed by Dutch women, considering it one of the key reasons behind the power and prosperity of the Dutch Republic. Samuel Pepys (1633–1703) (fig. 3) had a significantly different impression from his contemporary and fellow Englishman, John Ray (1627–1705), who described Dutch women as being "delighted with lascivious and obscene talk." Nonetheless, in his diary, Pepys described encounters with women he met in public spaces, including boats and taverns, with many of these interactions carrying a flirtatious or suggestive tone. While some women he met were overtly affectionate or openly engaging in flirtation, Pepys occasionally had suspicions about their intentions. Evidence in his entries suggests that some of these interactions might have been motivated by financial gain, hinting at possible exchanges of affection for money or gifts, which aligns with Pepys's awareness of and participation in London's social and sometimes transactional exchanges.

The Dutch translator of Boccaccio's De arte amandi (Art of Love, or De konst der vryery) noted that Dutch women were more "afkeerig" (reluctant or resistant) toward their suitors than their Italian counterparts. Lodovico Guicciardini (1521–1589), an Italian writer, merchant, and diplomat known for his detailed descriptions of the Netherlands during the sixteenth centuryDescrittione di Lodovico Guicciardini patritio fiorentino di tutti i Paesi Bassi altrimenti detti Germania inferiore (1567, Description of the Low Countries) described Dutch women as "frugal, busy, and always doing something, not only the housework." Ray reported that it was customary in Holland for married women, "even of the better sort," to kiss men—men who were no more than acquaintances—upon greeting them or taking their leave, a gesture he considered far too forward. He opined that Dutch women were "more fond of and delighted with lasciviousness and obscene talk than either the English or the French." Shaw marveled at the liberties the women took for granted: they ice-skated through the night, relieved themselves in public, and socialized openly in taverns without societal censure (fig. 4). One activity, however, seemed to make the strongest impression: the women of Holland engaged openly in conversation with men as they walked with them in the streets of town, unapologetically, sans chaperone.

Adriaen Pietersz van de Venne

1625

Oli on panel, 14.6 x 37.1 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Spanish writer Antonio Carnero noted in 1625 that Dutch women managed much of the business in the United Provinces, as many Dutchmen were often incapacitated by drink. In John Fletcher's (1579–1625) play The Little French Lawyer, one character remarks, "Nor would I be a Dutchman / To have my wife, my sovereign, to command me."The Little French Lawyer is a Jacobean era stage play, a comedy written by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger. It was initially published in the first Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647.