Business / Trades and Professions

A number of seventeenth-century travel journals remark on the presence of Dutch women in commerce, contributing to the idea of the "heroic Dutch businesswoman." While some view this as an exaggerated perception, documents from the time reveal that Dutch women were more actively involved in the economy than women in other countries, although the level of involvement varied across the Republic.

Although there were moral writings promoting home and family care as the proper focus of women’s efforts, there was also great admiration for a strong work ethic and numerous opportunities that flowed from the Republic’s enormous economic growth. While poor women have always had to work in some capacity, it is also true that women who were not in financial difficulty were active in the business world.

The scholar Danielle van den HeuvelDanielle W.A.G. van den Heuvel, Women and Entrepreneurship: Female Traders in the Northern Netherlands, c. 1580–1815 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007). examines three areas of female economic involvement: the marketplace, (fig. 1) with its stallholders and street vendors (fig. 2); the shop, selling anything from books to household goods; and the merchant’s office, engaging in international trade and finance. While men were more prominent in all of these areas, particularly in higher-income brackets, women were active in each.

Gabriel Metsu

c. 1657-1661

Oil on canvas, 97 x 84 cm.

Louvre, Paris

It was common for a woman to work at a stall selling meat, fish, (fig. 3) or vegetables in conjunction with her husband, but there were also women who owned and operated their own stalls. Little to no formal training was needed for this occupation, and sons and daughters alike learned the family trade. While specific records of other individual businesswomen from that era are limited, it is evident that women frequently participated in and sometimes led commercial activities. Widows, in particular, had legal rights to manage their late husbands' businesses, and many did so successfully in sectors like textiles, brewing, and trade.

Nicolaes Maes

c. 1658

Oil on canvas, 48.1 x 38.3 cm.

Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel

Adriaen van Ostade

c. 1620

Oil on panel, 34.5 x 45 cm

Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

The Milkmaid

In the seventeetnth-century, miklmaids (fig. 3) served as both highly functional and symbolic figures within Dutch society. Economically, these women were integral to the agrarian foundation of the Republic, handling dairy production, an essential aspect of local consumption and a significant export. Often drawn from working-class or rural backgrounds, their labor represented a broader cultural respect for industry and sustenance. Despite their modest economic standing, milkmaids played a crucial role in sustaining household economies, earning wages supplemented by in-kind benefits such as food and shelter.

Gesina ter Borch

c. 1669

Watercolor on paper, 24.3 x 36 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1657–1661

Oil on canvas, 45.5 x 41 cm.

The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

"Furthermore, milkmaids were portrayed in dual roles in Dutch art and emblematic literature as symbols of rural simplicity and, at times, romantic or moral ambiguity. In Vermeer’s The Milkmaid (fig. 5), for example, the milkmaid is elevated beyond her economic and social station. While the painting captures the tactile and visual richness of her work environment—portraying her garments, the textures of bread, and the flow of milk—it simultaneously imbues her with dignity and individuality. This depiction aligns with broader Dutch cultural ideals of hard work, moderation, and domestic virtue. However, the milkmaid is not merely a servant engaged in mundane tasks but a figure shaped by Vermeer’s intent to evoke timeless human values.While earlier depictions often carried suggestive overtones, Vermeer’s treatment avoids explicit narratives, focusing instead on an idealized, almost monumental portrayal."Walter Liedtke, The Milkmaid by Johannes Vermeer (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009).

In seventeenth-century Netherlands, spinners, weavers, seamstresses, and lace makers were integral to the textile industry, a cornerstone of the Dutch economy during the Golden Age. Their labor supplied domestic markets, fulfilled export demands, and contributed to the prosperity of urban and rural communities. These occupations attracted women from diverse social and economic backgrounds and were central to the country’s trade networks and material culture.

Spinners and Weavers

Gerrit ter Borch

c. 1652–1653

Oil on panel, 34.5 x 27.5 cm.

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Spinning and weaving were fundamental activities in the textile industry, with women participating in various stages of production. Linen and wool were the primary materials, reflecting the availability of flax grown locally and sheep farming in the Dutch countryside. Flax, after undergoing extensive processing, was spun into thread, which could be woven into linen. Wool followed a similar pattern, being carded, spun, and woven into textiles used for garments or trade.

Women working in spinning and weaving often came from modest households, contributing labor to supplement family incomes (fig. 6). This work could be done in the home or in communal workshops. In urban centers like Leiden and Haarlem, renowned for their textile production, professional weavers formed part of organized guild systems. Women, although excluded from full guild membership, often worked under male guild members or in ancillary roles, producing essential but undervalued labor.

The production of high-quality textiles for export was a major driver of the Dutch economy. Cloth from the Netherlands, particularly linen, was in demand across Europe and colonial markets. This created a steady, if modest, demand for women’s labor in spinning and weaving, ensuring these occupations’ enduring relevance.

Seamstresses

In the seventeenth-century Netherlands, clothing represented a significant expense for individuals and families, reflecting the labor-intensive processes involved in textile production and garment making. Within families, clothing was frequently passed from one generation to the next or among siblings. Parents often preserved garments for their children, with adjustments made to accommodate different sizes or changing fashions. Children’s clothing was typically repurposed from adult garments or passed down as younger members grew. This practical approach maximized the utility of each piece, reducing the need for frequent new purchases. For this reason, seamstresses played an essential role in maintaining and adapting clothing, particularly for those who could not afford to frequently purchase new items.

Seamstresses worked independently or for households, tailoring and repairing clothing for both functional and decorative purposes. This work required skill and precision, especially when catering to wealthier clients who demanded intricate designs or high-quality garments. Many seamstresses operated as part of informal economies, working out of their homes or small shops, often in urban settings.

Seamstresses contributed to the circulation and maintenance of clothing in a period when garments were highly valued and often reused or repurposed. Their labor was crucial to reducing waste and prolonging the life of textiles. Furthermore, seamstresses were essential in fulfilling the demands of a growing middle class, which sought to emulate elite fashion within their economic means.

Lace Makers

Lace making represented a specialized and labor-intensive craft. The creation of lace required meticulous techniques, often involving intricate patterns that were achieved through a combination of needlework or bobbin methods. Lace was a luxury item, and its production catered to the wealthiest strata of Dutch society as well as international markets.

The craft of lace making had its origins in earlier European traditions, particularly in regions like Flanders and Italy, which influenced Dutch artisans. Lace makers were typically women, often working in their homes or small workshops, and their products ranged from modest trimmings to elaborate designs for collars, cuffs, and decorative household items.

As a luxury good, lace served as a marker of social distinction, and its trade contributed to the Dutch Republic’s reputation as a center for high-quality craftsmanship. The demand for lace also intersected with broader economic trends, including the rise of global trade networks that allowed the export of luxury goods to colonies and other European states.

acemakers in the seventeenth-century Netherlands were typically women, ranging from young girls to adults, who often came from modest or working-class backgrounds. Many worked within a cottage industry model, crafting lace at home while managing other domestic responsibilities. In some regions, entire households or small communities were dedicated to lace production, particularly where the craft was well-established. The labor-intensive and time-consuming nature of lacemaking meant that while the work could be solitary, it was sometimes organized collectively in workshops, especially in areas where lace-making schools existed or where the craft was central to the local economy.

Lacemaking skills were frequently taught within families or through specialized schools. Young girls learned the intricate techniques from their mothers, older relatives, or local lacemakers, gradually honing their abilities. In regions where lace production was a significant industry, formal instruction was available in community-supported schools or religious institutions. Convents often played a critical role in educating girls in lacemaking, providing not only technical training but also instilling discipline and moral values. These convent schools aligned the craft with ideals of piety and industriousness, and the lace produced was often used for ecclesiastical purposes, offering students the opportunity to contribute to sacred and ceremonial settings.

Economically, while lacemaking offered only modest financial rewards for individual workers, it provided several important benefits. It allowed women to earn their own income, granting some financial autonomy within a male-dominated society. For many, it supplemented household earnings, particularly in rural areas where other employment opportunities were scarce. In regions such as Flanders, where high-quality lace was exported across Europe, lacemakers indirectly benefited from strong demand, even though merchants and middlemen retained the largest share of the profits. Additionally, mastery of lacemaking could elevate a woman’s status within her community, showcasing her dedication and skill.

Despite these benefits, lacemakers faced significant challenges. Wages were low due to the hierarchical structure of the industry, with most profits going to traders or merchants. The time required to produce even small pieces of lace limited their ability to increase earnings. Nonetheless, for many women, lacemaking remained one of the few viable ways to earn income while working from home.

Beyond its economic implications, lacemaking held broader cultural and social significance. The craft reflected ideals of industriousness and virtue, particularly in young women, and contributed to the material culture of the seventeenth century. Lace was a marker of wealth and refinement, its demand sustained by the social aspirations of the upper classes and by international trade networks. For lacemakers, their labor not only supported these trends but also represented a cultural tradition that linked craftsmanship with personal discipline and societal respect.

Shopkeeping

At the shopkeeper level, women were active in part due to their relatively high literacy and numeracy rates, fostered in a society driven by booming trade. Some women, such as Clementia van den Vondel,Clementia, Joost van den Vondel's sister, was a successful silk merchant in Amsterdam’s Warmoesstraat, continuing her husband’s business after his death with the help of her mother, Sara Cranen. Known for her strong-willed nature, Clementia had a complex relationship with her siblings, especially Joost, due in part to her critical view of his literary pursuits and his conversion to Catholicism. In her will, she arranged for her mother to oversee her business and household after her death, which added to the family tensions. Ultimately, Clementia handed her thriving business over to her son, Hans Jr., who maintained a good relationship with his uncle Joost. Sara Cranen, Clementia’s mother, had fled Antwerp for religious reasons and settled with her family in Amsterdam, where she established a hat and silk business that later supported her daughter and grandson’s ventures. Known for her entrepreneurship, Sara’s legacy was somewhat contentious within the family, as she noted in her will that Joost owed her a debt that he had to settle to claim his inheritance. Despite these familial strains, Sara’s business acumen laid a foundation for the Vondel family’s prosperity, and her determination influenced her children’s lives and careers. became quite successful. The sister of a famous poet Joost van den Vondel (1587–1679), Van den Vondel owned a silk shop that provided silk products and clothing accessories for individuals and also operated as a cloth wholesaler. After fleeing religious persecution in Antwerp, Sara Cranen settled in Amsterdam and helped establish the family's commercial ventures in hats and silk fabrics. Upon her husband's death, she continued to run the business and later formed a partnership with Clementia.

Susanna Veseler,Susanna Veselaer married the printer Jan Jacobsz Schipper (1616–1669) in 1650. She collaborated with printers Joseph Athias and Hendrik Wetstein. Her printers' mark identifies her as "Chez la veuve Schippers" (House of the widow Schippers). After her husband's death she actually expanded his business, making it one of the largest printing establishments in Amsterdam. the widow of a bookseller, ran the business for thirty years and was remarkably successful in both domestic and international markets, even though many of her books were Catholic. While this was officially frowned upon, profitable trade often excused such exceptions in Amsterdam at the time.

Women could even be found at the level of international trade, banking, and finance, particularly during the latter half of the century and into the next. This was in part due to changes in trade practices, allowing merchants to sell products on commission rather than directly managing their own sales. This arrangement became common for both men and women and was especially suited to upper-class women, who could manage their transactions primarily from home.

Nicolaes Maes

1656

Oil on canvas, 66 x 53.7 cm.

Siant Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis

Women could even be found at the level of international trade, banking, and finance, particularly during the latter half of the century and into the next. This was in part due to changes in trade practices, allowing merchants to sell products on commission rather than directly managing their own sales. This arrangement became common for both men and women and was especially suited to upper-class women, who could manage their transactions primarily from home.

But why were women so involved in business? One reason was the level of education, and another was the legal system. Unmarried women and widows had rights similar to those of men. A woman who became widowed often took over the family business, particularly if she had been involved prior to her husband’s death (fig. 8). If a married woman wished to have her own business during her husband’s lifetime, she could attain femme sole status.The term "femme sole" refers to a legal status in historical contexts where a married woman could operate as if she were single ("sole") in specific regards, particularly in business or property ownership. In the 17th-century Netherlands and other parts of Europe, married women typically fell under the legal authority of their husbands, limiting their ability to own property or run businesses independently. However, by attaining the status of femme sole, a married woman could bypass some of these restrictions and gain legal independence for business purposes.To achieve femme sole status, a woman might need her husband's consent or a legal provision granting her separate financial identity. This status allowed her to sign contracts, conduct business, and manage her own financial affairs without her husband's intervention. This legal flexibility made it possible for women to engage in trade, manage assets, and play a more active economic role, especially if their husbands were often absent due to work or travel. In the Netherlands, this arrangement reflected the pragmatic approach to wome's economic participation, particularly in the context of the trade-driven and seafaring economy. For example, if she was married to a seafaring husband, the court could allow her to carry on the business in his absence. These women were called "grass widows."In the context of the 17th-century Netherlands, "grass widows" referred to women whose husbands were temporarily absent, often due to long voyages associated with maritime trade, exploration, or military service. The Dutch Republic was a major seafaring nation during this period, with many men employed by organizations like the Dutch East India Company (VOC). These absences could last for months or even years, leaving their wives to manage households and, in many cases, oversee family businesses or estates independently. These women played a crucial role in the economic and social fabric of Dutch society. They were responsible for maintaining the household finances, raising children, and sometimes continuing their husbands' commercial activities. Once again, considerable flexibility was allowed in the interest of commerce.

Women, especially from affluent backgrounds, played also active roles in social welfare. They managed orphanages and administered charitable institutions, contributing to the social infrastructure of the Republic. An example of such involvement is the management of a women's prison, where incarcerated women were taught skills to earn an honest living upon their release, reflecting a progressive approach to rehabilitation and social reintegration. Many ran institutions dedicated to assisting the poor, the sick, orphans, and the elderly.

Women frequently served as regents or overseers of these institutions, a respected role that allowed them to contribute actively to the social fabric of their communities. In some cities, particularly Amsterdam, these charitable roles were formalized, with women assuming managerial responsibilities within charitable foundations. They organized fundraising efforts, oversaw day-to-day operations, and ensured that funds and resources were allocated properly. Protestant values, which emphasized care for the community, influenced this civic-minded approach, and many of these charitable works were tied to the Reformed Church.

Frans Hals' 1660 portrait of the Regentesses of the Old Men's Almshouse Haarlem (fig. 9) is a famous example, showing older women in a somber, dignified setting that reflects their roles in managing welfare for the elderly. These regentess portraits are distinct from other types of group portraits in that they emphasize the serious, charitable nature of their work rather than wealth or status alone. The women are often depicted in black clothing, characteristic of the period's modesty for those in public service, signifying their dedication to moral and civic duty.

Frans Hals

c. 1664

Oil on canvas, 170.5 x 249.5 cm.

Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem

House Maids

In seventeenth-century Netherlands, the relationship between maids and mistresses was a complex one, shaped by social hierarchies, economic dependencies, and evolving notions of domesticity. Dutch households often employed maids or domestic servants, who were typically young, unmarried women from rural or lower-class backgrounds seeking employment in urban centers. Mistresses, usually married women of the bourgeoisie or well-to-do merchant classes, oversaw household affairs and directly managed their maids, resulting in a dynamic marked by both cooperation and clear social distance. In a few documented cases, servants became loved members of the household, staying for many years and finally being pensioned off or left bequests in their master's wills.

Unmarried women from a genteel background but with no means of support would often work as a "waiting woman." This position, similar to a governess in later times, hovered somewhere between being a maid and a friend of the family. She would act as secretary, confidante, companion and lady’s maid, as her mistress required. She might be expected to sing or play an instrument to entertain her mistress and her friends, and to be a fine needlewoman.

Trustworthiness was crucial in this relationship, as maids had access to family spaces, daily routines, and personal belongings. They were often entrusted with important tasks, such as cleaning, cooking, childcare, and even managing finances, which required a significant degree of reliability (fig. 10 & 11). However, this trust was not absolute; maids were frequently under scrutiny due to concerns about theft, misbehavior, or moral transgressions. Cultural sources, including moral literature and paintings, often reflect this ambivalence—maiden servants were sometimes depicted as either loyal and virtuous or as potential disruptors of household order.

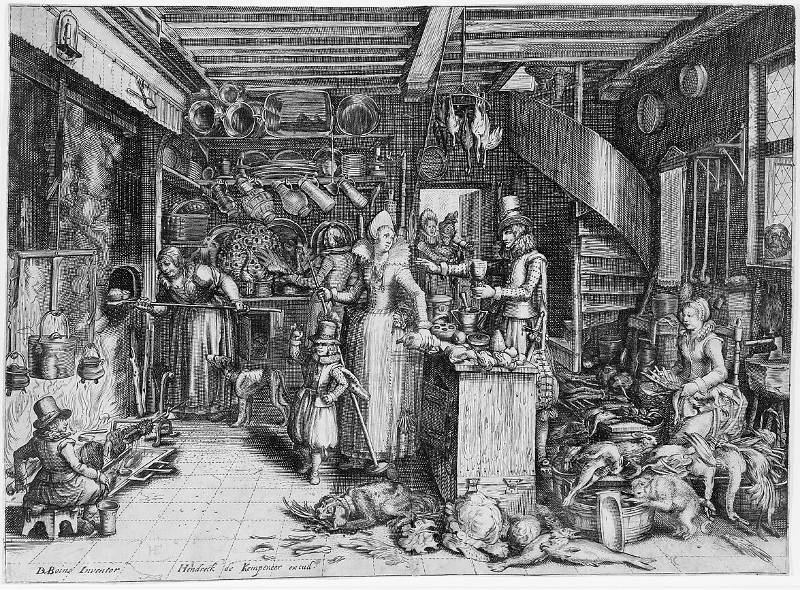

After David Vinckboons

c. 1600–1624

Engraving; Hollstein's first state of two, Sheet: 25.7 x 35.2 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

From a very young age, girls were hired by families as servants. Early each morning, they would rise to light the fire and prepare breakfast. Once the family had eaten, the servant’s duties included airing the rooms, making beds, washing clothes, and polishing tin and copper items. She was also responsible for shining the ironwork on shutters and, especially, scrubbing floors and the doorstep. Due to low wages and a surplus of women in urban areas, nearly every middle-class housewife could afford to employ a servant.

Pieter Janssens Elinga

1668

Oil on canvas, 82 x 99 cm.

Städel Museum,Frankfurt

Generally, servants were compliant and adaptable, often depending on the nature of their relationship with the mistress, and were almost considered part of the family. They shared meals with the household but were expected to observe their place. In comedies, servants were frequently ridiculed as the ones who spoke most at the dinner table. However, they remained subordinate, and impudence was not tolerated; if boundaries were crossed, even verbally, the issue could escalate to the Sheriff. Interestingly, many foreign observers noted that the Dutch refrained from physically

The boundary between familiarity and formality could blur, as some mistresses formed close bonds with long-serving maids. In certain cases, especially in Protestant households that emphasized moral propriety, mistresses might feel a sense of moral responsibility towards their maids, encouraging them to lead virtuous lives. Nonetheless, this relationship was governed by economic and social dependency, with the maid ultimately vulnerable to dismissal and often lacking legal protections. Consequently, the relationship between maid and mistress in the Dutch Golden Age reveals an intricate balance between trust, dependence, and social constraint within the domestic sphere.

Domestic servants, particularly maids, were often observed wearing attire that exceeded the modesty expected of their social status. This practice elicited societal concern, as clothing was a significant indicator of class distinctions during this period. The tendency of maidservants to adopt luxurious or fashionable clothing was perceived as a challenge to the established social hierarchy, leading to increased irritation and social unrest.

Domestic service was a prevalent occupation, particularly for young, unmarried women. While precise numbers are scarce, estimates suggest that in urban centers like Amsterdam, domestic servants constituted a significant portion of the population. for instance, in seventeenth-century Amsterdam, domestic workers were the largest group of wage-earners, with more than 95% being women. It has been estimated that approximately 12% of the population in European cities during this period were servants, with a significant concentration in urban areas. The employment of maids was not limited to the affluent; many middle-class families could afford to hire domestic help due to relatively low wages and a surplus of women seeking employment in cities. This accessibility led to a substantial number of households employing at least one maid to assist with daily chores and child-rearing responsibilities. While precise statistics on the exact percentage of families employing maids are scarce, the available data indicate that a significant proportion of urban households in the Dutch Republic during the 17th century included domestic servants as integral members of the household.

Most maids originated from rural areas or lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Seeking better economic opportunities, they migrated to cities to work in households of the burgeoning middle and upper classes. This migration was often part of a life-cycle service pattern, where young women worked as maids before marriage to accumulate savings and gain urban experience. Wages for domestic servants varied based on factors such as location, the employer's wealth, and the maid's experience. n Amsterdam during the eighteenth century, records indicate that servants working for affluent households could save a marriage budget that was between one-third and half of the capital that an unskilled man could save in the same amount of time. dditionally, maids often received room and board, and sometimes clothing, as part of their compensation. Despite the modest pay, domestic service provided young women with a means to support themselves and, potentially, their families. Overall, domestic service in the seventeenth-century Netherlands was a common and vital occupation for women from lower social strata, offering them economic opportunities and a pathway to eventual marriage and family life.

Dutch Maids in Contemporary Painting

In seventeent-century Dutch painting, maids appear ain a great many paintings of domestic interiors and mrket scenes, reflecting societal attitudes and domestic life of the period. These representations can be categorized into several themes. Artists such as Pieter de Hooch and Nicolaes Maes portrayed maids engaged in household tasks, emphasizing diligence and the moral virtue of labor. For instance, Maes's The Idle Servant (fig. 12) contrasts a sleeping maid with the industrious mistress, serving as a moral lesson on the value of hard work.

Nicolaes Maes

1655

Oil on panel, 70 x 53 cm.

National Gallery, London

Pieter Gerritsz van Roestraeten

c. 1660-1670

Oil on canvas, 73.5 × 63 cm.

Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem

Some works imbue the depiction of maids with sensuality, reflecting contemporary stereotypes of maids as objects of desire. Johannes Vermeer's A Maid Asleep illustrates a maid dozing beside a glass of wine, subtly suggesting themes of temptation and moral ambiguity. Similarly, Pieter Gerritsz van Roestraten's The Licentious Kitchen Maid (fig. 13) portrays a maid in a compromising position, highlighting concerns about propriety and social boundaries. Maids are also featured in satirical contexts, critiquing social norms and behaviors. In Jan Steen's The Dissolute Household, a chaotic domestic scene includes a maid participating in the disorder, serving as a commentary on the consequences of moral laxity within the household

Conversely, some artists present maids with dignity and focus, emphasizing their role in the household.Vermeer's The Milkmaid (fig. 14) depicts a maid absorbed in her task, highlighting the quiet dignity of domestic work.This portrayal deviates from the more common depictions of maids as either moral lessons or objects of desire, offering a nuanced view of their place in society.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1657–1661

Oil on canvas, 45.5 x 41 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Michael Sweerts

c. 1655-1660

Oil on canvas, 43.5 x 36.5 cm.

The Kremer Collection, Amsterdam

Particularly empathetic, A Young Maidservant (c. 1660) (fig. 15) by Michael Sweerts presents a young woman with a contemplative expression, capturing her humanity beyond her occupational role. The painting's realistic portrayal and attention to detail reflect Sweerts's interest in depicting ordinary people with depth and character. This approach aligns with the genre of tronie,Tronie paintings, popular in the Dutch Golden Age, depict expressive, often anonymous faces or character studies rather than identifiable portraits. These works capture exaggerated or characteristic facial expressions, costumes, or figures in distinctive attire to explore elements of human expression, emotion, and appearance. Unlike typical portraits, tronies were not intended to portray specific individuals; instead, they served as studies in character or types. Artists like Rembrandt and Vermeer created tronies to study various lighting effects, expressions, and exotic costumes. These works reflect the era’s fascination with individuality, exoticism, and the exploration of human nature, often blending elements of realism with a focus on exaggerated or idealized features, likewise offering affordable works for cleints who could not afford the masters' more leaborate and labor-intensive composions. character studies that focus on facial expressions and personalities rather than specific individuals. Unlike some contemporaneous artists who imbued such scenes with moralistic or sensual undertones, Sweerts's portrayal is marked by a respectful and empathetic perspective. His focus on the maid's absorbed demeanor and the meticulous rendering of her environment suggest an appreciation for the subtleties of daily life and labor.

These varied representations of maids in Dutch Golden Age painting reflect the complex social dynamics of the time, illustrating both the essential role of domestic servants and the moral and social concerns associated with their presence in the household.

Prostitution

drawn from: Lotte C. van der Pol, "The Whore, the Bawd, and the Artist: The Reality and Imagery of Seventeenth-Century Dutch Prostitution," Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 2:1-2 (Summer 2010)

Prostitution in the seventeenth-century Netherlands was a prevalent and organized aspect of urban life, especially in major cities such as Amsterdam. Legal records, particularly judicial archives, provide detailed accounts of the people involved and societal attitudes toward prostitution during this period. These records reveal the complex intersections of social, economic, and cultural factors that shaped the practice.

Legal and Social Framework

Prostitution was technically illegal, but enforcement varied widely depending on local circumstances. Cities like Amsterdam regulated the trade through legal and judicial means, aiming to control public morality while acknowledging its existence. Brothels, known as speelhuizen (playhouses), operated in specific areas, often under the oversight of local authorities. Arrests and prosecutions were usually driven by breaches of public order or concerns about spreading immorality.

The legal system kept meticulous records, particularly in Amsterdam, where the Confessieboeken der Gevangenen (Books of the Confessions of Prisoners) provide an invaluable source of information. These documents include interrogations of individuals accused of prostitution and related activities, offering insights into the lives of both prostitutes and brothel-keepers. Such records are unique in their detail and scope, capturing personal data such as names, ages, places of origin, and professions.

Demographics and Background

Most women involved in prostitution were from the lower socioeconomic strata of urban society. Many came from outside the cities where they worked. For example, in Amsterdam, only 20% of convicted prostitutes were native to the city, with others originating from the Dutch Republic's provinces, Germany, or Scandinavia. These women were typically young, with an average age of twenty-three, though both younger and older individuals were recorded. Contrary to stereotypes, prostitutes were not predominantly naïve rural servant girls lured to the city. Instead, many had prior experience in low-paid urban trades such as sewing, lace-making, spinning, or peddling. Some worked in service roles that overlapped with the hospitality industry, such as serving in inns or brothels, which facilitated their entry into prostitution.

Public Perception and Representation

Prostitution occupied a dual space in Dutch society, being both a visible reality and a subject of artistic and literary representation. In art, particularly genre paintings, brothel scenes often portrayed women as alluring and elegant, contributing to an idealized image. In contrast, written accounts from contemporaries like Bernard Mandeville offer a less flattering view, describing prostitutes as poorly educated, coarse, and marked by physical signs of manual labor. These discrepancies highlight the gap between artistic conventions and social realities.

Efforts to control the public image of prostitution included statutes regulating clothing. Laws prohibited lower-class women, including prostitutes, from wearing expensive fabrics, lace, or gold, as such attire was seen as morally corrupting and socially disruptive. Despite these restrictions, court records indicate that many prostitutes adopted upper-class fashions, often wearing secondhand gowns, elaborate headdresses, and makeup.

Judicial and Penal Practices

The judicial system played a central role in monitoring prostitution. Convicted women were often sentenced to institutions such as the Spin House, a corrective facility where they were required to work. In some cases, these women were displayed in their flamboyant attire as a moral lesson for the public. Authorities also confiscated luxury items, emphasizing the moral and social transgressions associated with their trade.

In sum, prostitution in the seventeenth-century Netherlands was shaped by a combination of economic necessity, urban migration, and societal regulation. While it was officially condemned, it remained an ingrained part of urban life, reflecting broader tensions between social norms, economic realities, and cultural expressions.

Prostitution in Dutch Painting

The theme of venal love was a recurring subject in Northern European art, particularly in the Netherlands during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Early depictions often focused on the parable of the prodigal son and its associations with taverns and brothels. These images, termed bordeeltjes, a diminutive form of bordelen (brothels). were typically moralistic, warning against vice through scenes filled with spendthrifts, gamblers, and harlots. By the sixteenth century, bordeeltje scenes were among the first examples of genre painting, depicting everyday life with symbolic layers. Procuresses and harlots played prominent roles, engaging in activities like seducing and robbing clients, while tavern and brothel settings reflected broader cultural attitudes towards luxury and gluttony.

Artistic depictions of brothel scenes evolved in the seventeenth century, especially under the influence of the Utrecht Caravaggisti. Painters such as Gerrit van Honthorst (1592–1656) introduced elements of elegance and theatricality, portraying richly dressed courtesans alongside procuresses, who embodied the negative stereotypes of old women. Dirck van Baburen (c.1595–1624) continued this tradition, with works like The Procuress reflecting a more explicit and titillating approach to the theme. These paintings, often focused on small, intimate brothels, diverged from the larger and more populated bordeeltjes of the previous century, mirroring changes in the regulation and prosecution of prostitution.

Painters like Jan Steen (c.1626–1679) and Hendrick Pot (c.1580–1657) expanded the subject further, incorporating moral lessons into their works. Steen, in particular, produced numerous bordeeltjes that depicted drunkenness, theft, and dubious sexual relations, often with a moralizing undertone. Despite the lively imagery, these paintings were not historical records of prostitution but rather visual interpretations rooted in artistic conventions and societal stereotypes. For example, procuresses were depicted as old and scheming, while courtesans appeared youthful and attractive, reflecting cultural biases rather than reality.

Although bordeeltjes contained elements true to life, such as small brothels, the presence of procuresses, and the potential for robbery, they omitted significant aspects of actual prostitution. Common realities like streetwalkers, police prosecution, or the prevalence of sailors as clients were excluded, while symbolic props and idealized figures dominated. These works served as both entertainment and moral commentary, blending societal critique with artistic traditions rather than offering a faithful representation of seventeenth-century Dutch prostitution.

Why Did Dutch Haute Bourgeoisie Collect Scenes of Prostitution?

Members of the haute bourgeoisieThe haute bourgeoisie, or upper middle class, represented a socially and economically influential group in 17th-century Europe, particularly in the Dutch Republic. These individuals, often wealthy merchants, professionals, and landowners, occupied a position just below the nobility. They were defined by their financial success, cultural refinement, and aspirations for social distinction. Members of the haute bourgeoisie were significant patrons of the arts, collecting paintings that reflected their values, interests, and societal position. Their taste ranged from moralizing genre scenes and still lifes to landscapes and portraits, often chosen to demonstrate both their prosperity and their adherence to cultural or religious ideals. Despite their moral standards, this group occasionally embraced more provocative works, such as brothel scenes, for their artistic merit, allegorical depth, or satirical commentary on human behavior. actively collected scenes of prostitution, a practice that may seem paradoxical at first, given the strict moral standards associated with both Protestantism and Catholicism. The appeal of brothel scenes to middle-class and upper-middle-class collectors in the Dutch Republic can be attributed to a blend of cultural, social, and artistic factors. These paintings often carried a moralizing message, serving as warnings against vice and excess. Collectors may have appreciated the instructive value of such works, seeing them as reminders of proper conduct within the context of a moral framework, although the barely constrained display of wanton gestures, cleavage, and suggestive behavior must have also catered to a fascination with the sensual and the forbidden, creating a complex interplay between morality and voyeuristic curiosity. Even devout individuals, like Vermeer’s Catholic mother-in-law, might have viewed these paintings as reinforcing religious and ethical values by vividly illustrating the consequences of immoral behavior.

At the same time, bordeeltjes were not purely condemnatory; they frequently incorporated humor and satire, offering a lively and theatrical commentary on human folly. Artists like Steen imbued their works with a playful tone, making them both engaging and entertaining. Collectors likely valued these paintings for their wit and ability to depict life’s absurdities, even when the subject matter revolved around morally questionable activities. This duality allowed such works to be enjoyed as humorous and thought-provoking reflections of society.

Dutch collectors also had a cultural fascination with scenes of everyday life, which extended even to the seedier aspects of society. Bordeeltjes, like taverns or marketplaces, were part of this broader interest in human behavior and social interaction. Though often exaggerated or stylized, these paintings offered glimpses into a world that was both familiar and intriguing, contributing to their appeal.

Finally, the artistic prestige of these works cannot be overlooked. Brothel scenes by renowned artists like Van Honthorst, Van Baburen, and Steen were admired for their technical mastery, innovative use of light, and compelling compositions. For collectors, owning such paintings was a mark of sophistication and taste, elevating the subject matter beyond its apparent crudeness. In the case of Vermeer’s mother-in-law, the decision to possess a brothel scene may have had less to do with its theme and more with the artistic merit of the work, reflecting the complex interplay between moral values, cultural interest, and aesthetic appreciation.

Vermeer and the Bordeeltjes

Even devout individuals, like Vermeer’s Catholic mother-in-law, the formidable Maria Thins (c.1593–1680), possessed a Procuress scene by Dirck van Baburen, which her son-in-law incorporated as a background prop in two of his compositions, The Concert and the later Lady Seated at a Virginal. Vermeer himself painted a Procuress early in his career, before shifting away from such themes to pursue the more prestigious history paintings and eventually his renowned domestic interiors, which became visual epitomes of balance, piety, and moral transcendence. This transition may indicate that he discovered his true artistic calling, found the bordeeltje genre unappealing, or more pragmatically, recognized that genre scenes were more commercially viable.

Some critics suggest that Vermeer’s inclusion of Van Baburen's Procuress in his works might have been an intentional signal to the viewer, hinting that the seemingly serene musical gatherings depicted in his paintings contained an air of ambiguity, possibly alluding to undisclosed sensual undertones. Alternatively, the inclusion could have elevated the scenes to suggest a refined yet worldly setting, indicating a high-class gathering with subtle complexities beneath its polished veneer.

Another hypothesis revolves around Vermeer’s relationship with Maria Thins, who provided significant financial support to him and his growing family. Featuring one of her prized possessions within his paintings could have been an act of deference or flattery, reflecting her status as both a patron and a maternal figure in his household. This gesture would align with the broader artistic tradition of referencing patrons or influential figures through their belongings as a mark of respect or gratitude.