The United Provinces of the Netherlands

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation established from 1579 to 1795 after seven Dutch provinces revolted against Spanish rule. This state, comprising Groningen, Friesland, Overijssel, Gelderland, Utrecht, Holland, and Zeeland, was the first independent Dutch state. Despite its small size and population of around 1.5 million, the Dutch Republic controlled a vast global trade network through the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and Dutch West India Company (GWC), establishing a significant colonial empire. The wealth generated from trade allowed the Republic to maintain a large navy and compete militarily against larger nations. It engaged in numerous conflicts, including the Eighty Years' War, the Dutch–Portuguese War, four Anglo-Dutch Wars, the Franco-Dutch War, and the War of the Spanish Succession, among others.

Cornelis Claesz van Wieringen

1621

Oil on canvas, 136.8 x 187 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

(A Spanish flagship is hit amidships by a smaller Dutch warship. It explodes in the middle of the Bay of Gibraltar. 25 April 1607: this is the first sea battle the Dutch fleet fights out with the Spanish beyond their own waters. It meets with great success. The Spanish losses are extensive: Spanish soldiers are catapulted into the air and drown in the sea. The painting is thus also meant to celebrate this spectacular Dutch victory.)

The Dutch Republic was known for its religious tolerance and intellectual freedom, fostering a cultural and scientific renaissance. This era, known as the Dutch Golden Age, produced renowned artists like Rembrandt and Johannes Vermeer, and scientists such as Hugo Grotius, Christiaan Huygens, and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. The Republic was a confederation of provinces with a high degree of independence, governed by the States General. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 expanded its territory by approximately 20%. The provinces were typically led by a stadtholder, often a member of the House of Orange, leading to a power struggle between the Orangists, who supported a strong stadtholder, and the Republicans, who favored a strong States General. This tension led to two periods without a stadtholder, known as the Stadtholderless Periods, which weakened the Republic's status as a major power.

During the seventeenth century, the Dutch Republic was composed of seven provinces, each contributing uniquely to the nation's political, economic, religious, and cultural landscape. This period, known as the Dutch Golden Age, was marked by significant prosperity, cultural richness, and advancements in various fields. Key figures from these provinces played pivotal roles in shaping the Republic and its identity.

Otto van Veen

1574

Oil on panel, 40 x 59.5 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Famished People after the Relief of the Siege of Leiden (fig. 1) attributed to Otto van Veen, illustrates a crucial episode from the Eighty Years' War, specifically the relief of Leiden in 1574. This siege was significant in the struggle of the Dutch provinces against Spanish rule and became an emblematic event in the path toward independence.

The siege, which began in October 1573, led to severe famine as Spanish forces encircled Leiden, blocking supplies and aiming to force surrender. However, through a strategic decision to breach dikes, the Dutch flooded the surrounding area, allowing a fleet of ships to bring supplies and reinforcements to the besieged city. The resulting Spanish withdrawal marked a powerful victory for the Dutch forces.

The relief of Leiden had broader importance in the formation of the United Provinces. The city’s survival and the fortitude of its citizens became symbols of resistance and unity. Leiden’s defense fueled a sense of shared identity among the northern provinces, contributing to the resolve that culminated in the eventual establishment of the Dutch Republic. Furthermore, as a token of gratitude, the nascent government established Leiden University in 1575, fostering intellectual and cultural development central to the Dutch Golden Age.

Holland

Holland was the most influential and populous province, driving political decisions within the States General, the federal assembly of the Republic. Amsterdam, the capital, was a global hub for trade, finance, and culture. The province's economy thrived on maritime trade, shipbuilding, and banking. Amsterdam's harbor was one of the busiest in the world, facilitating the import and export of goods like spices, textiles, and precious metals. The VOC (Dutch East India Company) (VOC) and the Dutch West India Company (WIC), both headquartered in Amsterdam, were instrumental in establishing Holland's dominance in global trade. The province was also a leader in banking, with Amsterdam developing into an early financial center. While Calvinism was the dominant religion, Holland was known for its relatively high degree of religious tolerance, accommodating various Protestant sects, Catholics, and Jews. Culturally, Holland was at the forefront of the Dutch Golden Age, with renowned artists like Rembrandt and Vermeer. Key figures included Johan de Witt, a statesman crucial in the administration and governance of the Republic, Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft, a historian and poet, and Hugo Grotius, a jurist who laid the foundations of international law.

Zeeland

Zeeland played a critical role in naval defense and maritime trade, with important ports like Middelburg and Vlissingen. The province's economy was heavily oriented towards maritime activities, including fishing, trade, and shipbuilding. Zeeland benefited significantly from the salt trade, as well as the production of textiles and grain. The region's strategic position at the mouth of the Scheldt River allowed it to control access to the rich agricultural lands of Flanders and Brabant. The religious landscape was predominantly Calvinist with a degree of tolerance for other faiths. Culturally, Zeeland contributed to maritime arts, including nautical literature and painting. Significant figures from Zeeland included Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, an influential political figure crucial in the early formation of the Dutch state, and Piet Hein, a naval commander known for capturing the Spanish Silver Fleet.

Utrecht

Utrecht remained significant both politically and economically, with a mixed economy of agriculture, trade, and textiles. The province had a strong agricultural base, including dairy farming and grain production. Utrecht's location along key trade routes connecting the northern and southern provinces of the Republic made it an important center for commerce and trade. The city's religious institutions also played a role in the local economy, attracting pilgrims and scholars. Utrecht's religious history as a Catholic stronghold before the Reformation left a legacy of beautiful medieval churches. After the Reformation, Utrecht became predominantly Protestant but retained a substantial Catholic community. The University of Utrecht, founded in 1636, became an important institution for higher learning. Notable figures included Adriaan Floriszoon Boeyens (Pope Adrian VI) and Gijsbert van Hogendorp, a statesman who contributed to Dutch constitutional reforms.

Gelderland

Gelderland's diverse geography supported a mixed economy of agriculture, trade, and industry. The fertile river valleys of the Rhine, Waal, and IJssel supported extensive agriculture, including the cultivation of grains, fruits, and vegetables. The province also had significant livestock farming, particularly cattle and sheep. Gelderland's forests provided timber, which was an important resource for building and heating. The province's cities, such as Nijmegen and Arnhem, were centers of trade and craftsmanship, producing goods like pottery, leather, and textiles. Gelderland had a varied religious composition, with both Calvinist regions and significant Catholic communities. The province contributed to Dutch culture with local histories and literature. Key figures included Maarten Harpertszoon Tromp, a distinguished naval commander, and Rutger Jan Schimmelpenninck, a statesman involved in political reorganization.

Overijssel

Overijssel was known for its agricultural output, trade, and small-scale industries. The province was largely based on agriculture, with a focus on grain, livestock, and dairy farming. The province also had important industrial activities, particularly in cities like Deventer and Zwolle, which were known for their production of textiles, beer, and metal goods. Overijssel's location along the IJssel River facilitated trade and transport, connecting it to the major trade routes of the Republic. The province also played a role in the brewing industry, with local breweries producing beer for domestic consumption and export. Overijssel was predominantly Calvinist, with some religious diversity. It was noted for its medieval towns, rich in historical architecture, and it played a role in the broader educational and religious life of the Republic. Coenraad van Beuningen, a diplomat, and Herman Boerhaave, a pioneering figure in medicine and chemistry, were notable figures from Overijssel.

Friesland

Friesland maintained a high degree of autonomy and had a distinct cultural identity. The province's economy was heavily based on agriculture and dairy farming, with Friesland being renowned for its cheeses and other dairy products. The region's extensive network of waterways supported a significant fishing industry, particularly in herring and other fish. Friesland also engaged in maritime trade and shipbuilding, leveraging its coastal location. The province had a strong tradition of craftsmanship, producing textiles, ceramics, and metalwork. The Frisian cities, such as Leeuwarden and Harlingen, were centers of trade and commerce, particularly in livestock and agricultural products. Friesland was predominantly Protestant, with a significant presence of Mennonites. The province had a rich literary tradition in the Frisian language. Significant figures included Pieter Stuyvesant, the last Dutch Director-General of New Netherland, and Gysbert Japicx, a poet and writer who preserved the Frisian language.

Groningen

Groningen, the northernmost province, was strategically important, often balancing influences from the Republic and neighboring German territories. The province had a mixed economy, with significant contributions from agriculture, fishing, and trade. The fertile soil supported the cultivation of grains, particularly wheat and barley, as well as other crops like flax and tobacco. The city of Groningen, the provincial capital, was a major trading center, dealing in agricultural products, textiles, and other goods. The province also had a significant fishing industry, with a focus on herring and other North Sea fish. Groningen was known for its production of peat, which was used as a fuel source. The province's connection to the trekschuit network facilitated the transport of goods, enhancing its economic activities. The University of Groningen, established in 1614, became a center for scientific and philosophical thought. The religious landscape in Groningen was predominantly Protestant, with a notable Catholic minority. Key figures included Ubbo Emmius, the first rector of the University of Groningen, and Adriaan Metius, a mathematician and astronomer.

Religion

Gijsbert Jansz. Sibilla

c. 1635

Oil on canvas, x cm

Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht

In the seventeenth-century Netherlands, religion deeply influenced political and social life, creating a unique blend of moral oversight and practical tolerance. Calvinism, particularly the Dutch Reformed Church, was central to the Republic’s identity and governance. The struggle for independence from Catholic Spain had strengthened this Protestant identity, with Calvinism serving almost as a unifying civic religion. While the Republic did not enforce Calvinism as strictly as some European powers did their official religions, government positions and political influence were generally reserved for Calvinists, who saw a religious duty in upholding public morals and social order.

Catholicism, though officially marginalized, remained significant, especially in the southern provinces, where many continued to practice their faith. Catholics were tolerated but faced legal restrictions, creating a complex coexistence: they integrated into Dutch society but kept distinct religious identities. This pluralistic approach reflected the pragmatic tolerance that characterized the Dutch Republic, which became known as a haven for religious minorities. Lutherans, Anabaptists, and Jews, drawn by the Republic’s relative freedom, contributed to the economic and cultural growth of cities like Amsterdam. However, this tolerance was largely conditional—minority groups could worship as they wished as long as they didn't disrupt social order or seek too much political influence.

As open Catholic services were banned, worship often took place in schuilkerken (hidden churches), discreetly concealed within ordinary buildings like houses or warehouses to avoid detection. These hidden churches allowed Catholic communities to maintain their religious practices in relative secrecy, often with the tacit acceptance of local authorities. One notable example that survives today is the Ons' Lieve Heer op Solder (Our Lord in the Attic) in Amsterdam (fig. 2), a Catholic church ingeniously tucked away in the attic of a canal house. Established in 1663, this hidden church offers a glimpse into the lives of Catholics during a time when they had to worship discreetly to avoid persecution.

The social and economic landscape also benefited from this diversity. Religious minorities often found niches within Dutch cities; Jewish communities, for instance, played essential roles in trade and finance, while Anabaptists were known for their craftsmanship and contributions to industries like textiles. These groups helped bolster the Republic’s reputation as a thriving hub of commerce and finance, aligning well with its open economic policies.

The Dutch Reformed Church also maintained a strong moral influence over society. Church leaders encouraged values aligned with Calvinist teachings, overseeing matters like marriage, family life, and even public behavior. Local church councils held significant authority, guiding communities to conform to accepted moral standards and creating a cohesive social environment. Community gatherings, church attendance, and religious festivals reinforced both moral discipline and communal bonds.

In this way, the seventeenth-century Netherlands developed a social structure that combined religious adherence with an unusual degree of tolerance, fostering a society where Calvinist dominance coexisted with pragmatic acceptance of religious diversity, contributing to both social stability and economic dynamism.

In the seventeenth-century Netherlands, religious affiliations varied across regions and evolved over time. While precise percentages are challenging to determine, the general distribution was as follows:

- Calvinism (Dutch Reformed Church) - Around 45–55% of the population: Predominant in the northern provinces, especially Holland, Zeeland, and Friesland. Calvinism was the official state religion, and its followers constituted a significant portion of the population in these areas.

- Roman Catholicism - About 35–40%: Maintained a strong presence in the southern provinces, notably North Brabant and Limburg. Despite the Protestant Reformation and the establishment of Calvinism as the state religion, many in these regions remained Catholic.

- Lutheranism - Roughly 2–5%: Had a smaller following, primarily among German immigrants in urban centers like Amsterdam. Lutherans were part of the broader Protestant community but were less numerous compared to Calvinists.

- Anabaptists and Mennonites - Estimated at 3–4%: These groups, advocating for adult baptism and separation from state affairs, had a modest presence, particularly in Friesland and Groningen. They were part of the Radical Reformation and faced varying degrees of tolerance.

- Judaism - Less than 1%: The Jewish community, comprising both Sephardic Jews from Spain and Portugal and Ashkenazi Jews from Central and Eastern Europe, was concentrated in cities like Amsterdam. They were a small but influential minority, contributing to commerce and culture.

- Other Protestant Sects Collectively - Aound 1–2%: Various other Protestant groups, including Huguenots (French Protestants) and English Dissenters, sought refuge in the Netherlands due to its relative religious tolerance. Their numbers were modest but notable in urban areas.

It is important to note that the Dutch Republic was known for its relative religious tolerance, allowing for a diverse religious landscape. However, the dominance of Calvinism in political and social spheres influenced the extent of freedom and acceptance experienced by other religious groups.

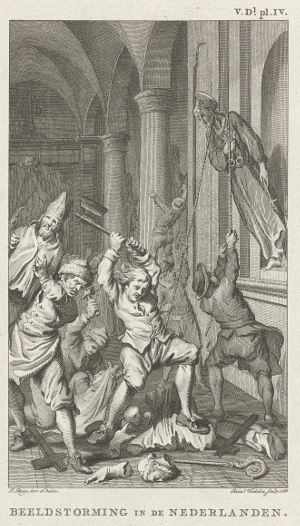

Beeldenstorm

In the sixteenth century, the Netherlands experienced a significant wave of iconoclasm, known as the Beeldenstorm or "Iconoclastic Fury," which profoundly impacted religious art and architecture. This movement, peaking in 1566, was driven by Protestant reformers who viewed religious images as idolatrous, leading to the widespread destruction of Catholic paintings, statues, and church decorations. The Beeldenstorm was not merely a result of doctrinal disputes but also intertwined with political tensions, economic factors, and resistance against Spanish rule. The iconoclastic actions varied across regions, with some areas witnessing organized groups systematically defacing religious symbols, while others saw spontaneous outbreaks of violence against church properties. Notably, cities like Antwerp and Ghent experienced extensive damage to their religious sites. The destruction included altarpieces, stained glass windows, and other ecclesiastical art forms, leading to a significant loss of cultural heritage.

Reinier Vinkeles (printmaker), after Jacobus Buys

1786

Etching on paper, 19.2 x 11.6 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Beeldenstorm, however, would have a profound impact on the trajectory of Dutch art, particularly painting. This widespread destruction of religious images, driven by Protestant reformers who viewed such imagery as idolatrous, led to a significant decline in the production of religious art in the Netherlandsm with Dutch artists shifting their focus toward secular subjects, giving rise to new genres that would define the Dutch Golden Age of painting. Artists began to explore landscapes, still lifes, and scenes of everyday life, reflecting the changing societal values and the reduced role of the Catholic Church in public life. This transition not only marked a departure from traditional religious themes but also laid the groundwork for future artistic movements in the Netherlands, emphasizing individual expression and everyday subjects that would continue to resonate in art well into the seventeenth century and beyond.

The Beeldenstorm, however, would have a profound impact on the trajectory of Dutch art, particularly painting. This widespread destruction of religious images, driven by Protestant reformers who viewed such imagery as idolatrous, led to a significant decline in the production of religious art in the Netherlandsm with Dutch artists shifting their focus toward secular subjects, giving rise to new genres that would define the Dutch Golden Age of painting. Artists began to explore landscapes, still lifes, and scenes of everyday life, reflecting the changing societal values and the reduced role of the Catholic Church in public life. This transition not only marked a departure from traditional religious themes but also laid the groundwork for future artistic movements in the Netherlands, emphasizing individual expression and everyday subjects that would continue to resonate in art well into the seventeenth century and beyond.

During the Beeldenstorm, many Dutch churches were stripped of their religious imagery, leaving interiors characterized by unadorned white walls, with organs and pulpits as the only decorative elements allowed. In the mid-1600s, artists such as Gerard Houckgeest (c. 1600–1661) and Emanuel de Witte(1617–1692) captured these transformed spaces in their works, reflecting the austere aesthetic that emerged from Protestant iconoclasm.

Houckgeest was among the first to depict these simplified church interiors. His paintings often feature precise linear perspectives, drawing the viewer's eye through the nave toward the chancel. The absence of religious iconography emphasizes the architectural elements, such as columns and arches, highlighting the structural beauty of the space. Houckgeest's works frequently include figures engaged in everyday activities, underscoring the church's role as a communal gathering place. De Witte further developed this genre, focusing on the interplay of light and shadow within these vast, unembellished interiors. His paintings capture the serene atmosphere of the reformed churches, with sunlight streaming through large windows, illuminating the whitewashed walls and casting intricate patterns on the floor. De Witte's attention to the effects of light not only enhances the sense of space but also imbues the scenes with a contemplative quality.