Quill

Quills were traditionally made from the flight feathers of large birds, with the best ones coming from the primary wing feathers—usually the five outermost ones—on the left wing. These feathers curve away from a right-handed writer's hand, allowing better visibility and control. Goose feathers were most commonly used in Europe, but swan, turkey, and crow feathers were also prized. For very fine lines, such as in manuscript illumination or delicate drawings, crow and raven quills were preferred, while swan feathers were favored for large, sweeping writing.

The preparation of a quill was a careful process. Fresh feathers were first hardened by aging or by plunging them into hot sand, which dried the interior of the shaft (calamus) and made it less flexible. Some scribes or artists also tempered the quill in warm ashes or bake ovens. After hardening, the outer membrane and any remaining soft tissue were scraped off, and the quill was then shaped using a penknife—hence the term. The nib was carefully split with a fine cut down the center to allow ink flow, and the tip was shaped to a point or chisel according to the desired thickness of the line.

Salomon Koninck

1639

Oil on panel, 66.8 x 51.1 cm.

Johnny van Haeften, London

Quills needed regular maintenance. The tips wore down quickly, so artists and writers often kept a knife at hand to recut the point. Because quills could fray or splay after repeated use, they were frequently replaced. Still, for centuries, they remained the favored tool for ink drawing and writing, valued for their responsiveness and subtlety.

In the hands of 17th-century Dutch artists, a well-prepared quill could produce everything from the delicate hatching lines of a portrait study to the quick, expressive flourishes of a landscape sketch. The medium's physical demands—requiring lightness, confidence, and careful handling—shaped the very character of the drawings made with it.

Raking Light

Raking light is the illumination of objects from a light source at a strongly oblique angle almost parallel to the object's surface (between 5º and 30º with respect to the examined surface). Under raking light, tool marks, paint handling, canvas weave, surface imperfections and restorations can be visualized better than with light coming from different angles. In some instances raking light may help reveal pentimenti or changes in an artist's intention. In the case of wall paintings, raking light helps show preparatory techniques such as incisions in the plaster support.

The term "raking light" may also be used to describe a strongly angled light represented in illusionist painting, although not strictly between 5º and 30º. Raking light gives volume to objects and accentuates texture. It is best used to create dramatic or moody images.

Painters instinctively avoid the lowest angles of raking light because they divided solid objects into two essentially equal parts: a face would be half in light and half in shadow, which tends to have a flattening effect. Moreover, raking light create cast shadows that run parallel to the picture plane, so they do not suggest spatial recession as well as shadows that are cast backward by light originating from a higher angle. Since it is easier to evaluate an object's form, color and texture when it is illuminated rather than when it is in shadow, a wider angle of light is generally preferable. Often, painters use three-quarters lighting which reveals the great part of an object's surface but creates at the same time a strong sense of volume.

Rapen

Rapen, which means "stealing" or "borrowing," is a Dutch term widely used in the seventeenth century when discussing artistic competition and emulation. Rapen was approved by Dutch art theorists of borrowings provided that they were integrated into painting and might appear unrecognizable. Using a play on words—in Dutch rapen is the plural of raap, or "turnip"—the Dutch painter and art writer Arnold Houbraken (1660–1719) recommended that "stolen" fragments should be "welded, molded in the mind as though it were stewed in a pot, and prepared and served with the sauce of ingenuity if it is to prove flavorful." While rapen could be seen as a practical way of building upon artistic tradition, it also bordered on imitation when overused. Some critics in the period regarded excessive borrowing as a lack of invention, while others saw it as a natural part of artistic development.

Ras schilderen

Ras schilderen is the Dutch term for alla prima painting.

Ratio / Matematical Proportion

Mathematical ratios have long played a role in artistic composition, shaping the way artists structure their works to create balance, movement, and harmony. From antiquity to the Renaissance, theorists and practitioners sought ideal proportions that would appeal to the human eye, often turning to geometry and numerical relationships to guide their designs. Euclid explored the mathematical principles underlying proportion, and later, Renaissance thinkers such as Luca Pacioli (c. 1447–1517) formalized these ideas in treatises on aesthetics and design. The study of ratios extended beyond painting into architecture, music, and even philosophy, reinforcing the belief that numerical harmony reflected a deeper order in nature.

In seventeenth-century Dutch painting, compositional balance was achieved through empirical practice rather than strict adherence to theoretical ratios. Dutch artists, deeply attuned to the effects of light, space, and perspective, organized their works using structures that felt natural and visually engaging. Painters such as Vermeer, Pieter de Hooch (1629—c. 1684), and Emanuel de Witte (1617–1692) arranged their domestic interiors with a careful distribution of visual weight, often using architectural elements to guide the eye through the scene. Still-life painters, including Willem Claesz. Heda (1594–1680) and Pieter Claesz (1597–1660), positioned objects with an intuitive sense of proportion, creating compositions that felt both structured and organic. Landscape painters, notably Jacob van Ruisdael (1628–1682), developed spatial depth through compositional divisions that echoed naturalistic observation. While Dutch artists may not have explicitly applied mathematical formulas, their work reflects a refined understanding of proportion that contributed to the extraordinary realism and harmony characteristic of their paintings.

Divine Proportion — This name was popularized during the Renaissance, particularly by Luca Pacioli in his 1509 book De divina proportione.

• Golden Section — A common term used in classical mathematics and aesthetics.

• Golden Mean — Another variant often used in discussions of art and philosophy.

• Extreme and Mean Ratio — A more technical, older mathematical term used by Euclid.

• Phi (Φ) — Named after the Greek letter ϕ (phi), which represents the numerical value of approximately 1.6180339887.

• Fibonacci Ratio — Though technically not the same, the golden ratio is closely related to the Fibonacci sequence, as the ratio of consecutive Fibonacci numbers approaches Φ. The ratio of one-third to two-thirds is commonly associated with the Rule of Thirds in composition and design. While not a strict mathematical ratio like the golden ratio, it is widely used in art, photography, and design for balance and visual harmony. Some related terms and concepts include:

• Rule of Thirds — A guideline in composition where an image is divided into nine equal parts using two horizontal and two vertical lines, with key elements placed along these lines or their intersections.

• Harmonic Proportions — A broader term that encompasses aesthetically pleasing divisions of space, including one-third/two-thirds ratios.

• Dynamic Symmetry — A compositional system that sometimes incorporates the Rule of Thirds, as well as other mathematical and geometric principles.

• Simple Ratio Composition — In painting, this can refer to any intentional division of space that avoids symmetry and creates visual interest.

Unlike the golden ratio, which has a mathematical foundation in Φ (1.618), the 1:2 ratio is more of a practical visual tool based on human perception.

Realism

Realism in the visual arts refers to the faithful representation of objects, people, and scenes as they appear in the natural world, emphasizing accuracy in proportion, perspective, lighting, and texture. The pursuit of realism is tied to the desire to convey visual truth, communicate stories effectively, and assert mastery over the visible world. However, this goal has been interpreted differently across cultures and eras, shaped by spiritual beliefs, social functions of art, and evolving technical abilities.

Cave art, such as the paintings in Lascaux and Chauvet, created between 30,000 and 15,000 , demonstrates an early form of realism that is striking in its anatomical accuracy and the sense of movement conveyed in the depiction of animals. This realism was not aimed at mere imitation of nature but was likely intertwined with ritualistic or symbolic functions, perhaps serving as a means to exert control over the animals or to invoke success in hunting. The use of shading, overlapping forms, and implied motion suggests a sophisticated observational skill, indicating that realism was already valued as a way to capture the essence and power of the natural world.

In ancient Egypt, by contrast, realism was subordinated to symbolic and hierarchical purposes. Egyptian art did not adhere to a strict canon of proportion and perspective. Hierarchical proportions were crucial for conveying the social and spiritual order, with size and positioning used to emphasize the importance of gods, pharaohs, and nobility over commoners and enemies rather than any observed reality. This approach ensured that the visual language of art reinforced the divine authority and eternal status of rulers, aligning with the Egyptians' belief in the afterlife and cosmic order.Figures were depicted in composite view—heads in profile but torsos facing forward—to communicate the most recognizable aspects of each part. This stylized approach was not due to a lack of technical skill; Egyptian artists were highly adept at carving and painting. Rather, the goal was to convey timelessness, divine order, and the status of individuals within a structured society. Realism was sacrificed to ensure that the representation aligned with spiritual and societal conventions.

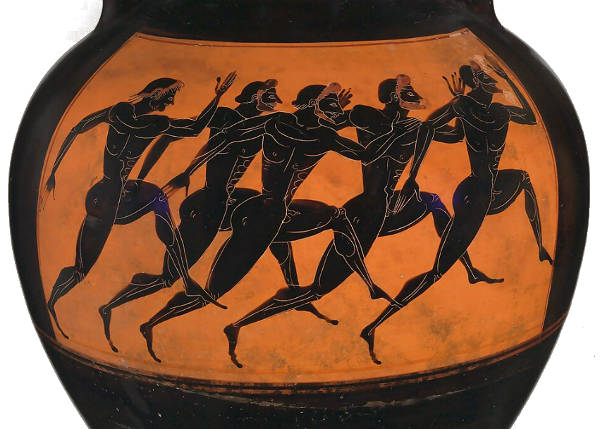

Ancient Greece marked a significant shift towards realism, driven by a philosophical pursuit of ideal beauty and truth. Greek sculptors such as Polykleitos (c. fifth century ) and Praxiteles (c. 395–c. 330 ) developed naturalistic forms based on careful study of human anatomy and proportion. The use of contrapposto in sculpture, creating lifelike stances, reflects a quest to capture the ideal human form realistically while adhering to mathematical proportions. However, this realism was not an end in itself but a means of approaching an idealized vision of humanity, balanced between naturalism and perfection.

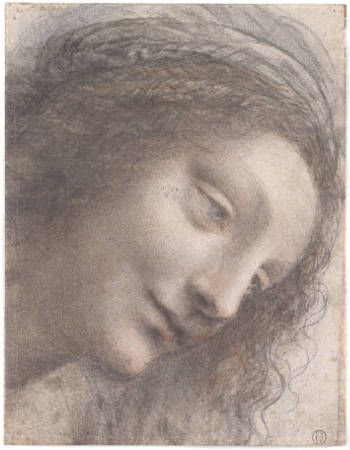

During the Renaissance, realism reached a new level of sophistication through the rediscovery of linear perspective, anatomical study, and the application of light and shadow (chiaroscuro). Artists like Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Michelangelo (1475–1564) explored realism not only as a technique but as a way to express complex emotions, spirituality, and the humanity of their subjects. The scientific curiosity of the Renaissance expanded the technical vocabulary available to artists, enabling them to depict depth, volume, and atmospheric effects with unprecedented accuracy.

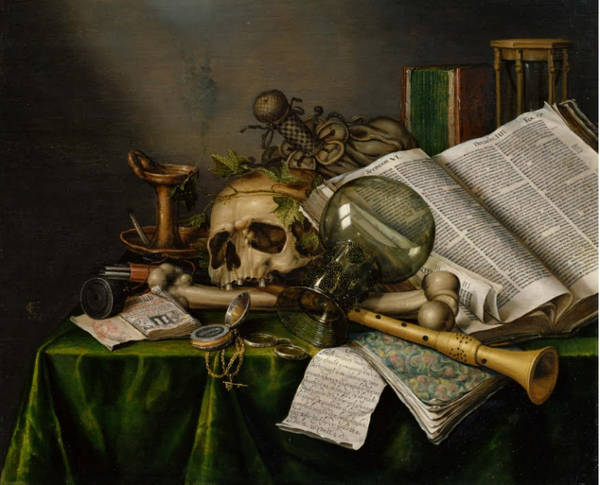

In seventeenth-century Netherlands, realism achieved its apogee in the works of artists who elevated the ordinary to the extraordinary. Dutch painters embraced realism as a means to reflect the material wealth, domestic virtues, and moral complexities of their society. This realism was often microscopic in detail, capturing textures, light effects, and the minutiae of everyday objects with astonishing precision. The popularity of genre scenes, landscapes, and still lifes, as seen in the works of Pieter de Hooch (1629–c.1684), Willem Claesz. Heda (1594–1680), and Vermeer, reflects a culture deeply invested in the truthful representation of its world. Unlike Italian Baroque, which pursued dramatic and emotional realism, Dutch realism was characterized by restraint, clarity, and a focus on the observable.

Tracing the development of realism in art involves examining how various components—outline, form, shadows, volume, relief, overlap, perspective, and atmosphere—emerged and evolved. Each of these elements contributed incrementally to the pursuit of a more accurate depiction of the natural world. Understanding the chronological order in which they appeared helps to clarify how realism was gradually constructed. Howeverm the development of key components of realism in art did not follow a uniform chronological order but was instead marked by localized advancements shaped by social and religious needs. Different cultures prioritized aspects such as outline, form, or perspective based on their symbolic, spiritual, or societal functions for art, leading to uneven but contextually significant progress in achieving realism. Forexample, cave art, such as that found at Lascaux and Chauvet, often conveys a remarkable sense of movement through techniques like overlapping limbs, dynamic poses, and the careful placement of lines to suggest motion, especially in depictions of animals. This emphasis on movement likely served both ritualistic and practical purposes, perhaps aiming to capture the vitality of prey or to evoke success in hunting. In contrast, ancient Egyptian art presents figures in a rigid, timeless stance, using composite views that combine profile heads with frontal torsos and legs.

The first component to emerge was the outline. Early examples of this can be seen in cave paintings at sites like Chauvet and Lascaux, dating back about 30,000 years. These artists used simple yet effective outlines to define the contours of animals, capturing recognizable shapes with remarkable accuracy. The use of outline was not only a way to delineate forms but also an essential tool for making sense of the complex natural world. The clean, unbroken lines provided clarity, helping to isolate subjects from their backgrounds. Ancient Egyptian art, too, emphasized the outline, creating distinct profiles of figures and objects with a high degree of precision.

Next came form—the depiction of three-dimensionality within a two-dimensional space. Even in prehistoric times, cave artists attempted to convey form by subtly varying line thickness and using rudimentary shading techniques. The emergence of form became more pronounced in ancient Greece, where sculptors developed a nuanced understanding of human anatomy, as seen in the kouros figures and, later, the contrapposto stance. This focus on form was not limited to sculpture; Greek vase painting also demonstrated an increasing sophistication in rendering the human body with volume and a sense of weight.

Unknown author

4th century (350–200)

Wall painting

Small Royal Tomb, Verghina, Macedonia

Closely related to form was the introduction of shadows to convey depth and spatial relationships. The term skiagraphia, meaning "shadow painting," was used to describe a technique attributed to Apollodoros of Athens (c. fifth century ). This method involved the use of light and shadow to modeling figures more convincingly, adding a sense of depth and three-dimensionality to flat surfaces. Skiagraphia marked a significant step forward in the pursuit of realism, as it allowed Greek artists to depict how light interacts with form, creating lifelike representations that bridged the gap between two-dimensional painting and three-dimensional sculpture. This technique not only improved the illusion of volume but also contributed to a more dynamic interaction between figures and their settings, laying the groundwork for the chiaroscuro effects that would later be refined during the Renaissance.The development in shadow painting is clearly evident in the frescoes of Pompeii (c. 1st century AD), where artists used shading to suggest the curvature of objects and figures. Shadows allowed for a more convincing portrayal of light sources and contributed to the illusion of three-dimensionality. However, these shadows were often more symbolic than realistic, lacking the nuanced gradations seen in later works.

Relief and overlap were other early advancements. Ancient Egyptian art employed low relief to create a sense of depth on temple walls and tombs, while Greek sculptors perfected high relief in friezes, providing a more lifelike appearance. Overlap, used to suggest which figures or objects were in front of others, was a simple but effective technique for indicating spatial relationships. Examples of this can be found in Assyrian reliefs and Roman mosaics, where layers of figures and objects helped to convey a sense of crowding and depth.

The significant leap towards realism came with the development of perspective. Ancient Romans, as evidenced by the frescoes in Pompeii, began experimenting with linear perspective to create the illusion of depth. However, it was during the Renaissance that perspective was formalized into a system. Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) demonstrated the principles of linear perspective, which Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) codified in his treatise De pictura. This breakthrough allowed artists to construct convincingly deep spaces on flat surfaces, positioning viewers within the scene. The use of vanishing points and orthogonal lines became a hallmark of Renaissance realism, evident in works like Raphael's The School of Athens.

Following perspective, the use of volume became more sophisticated, particularly through the technique of chiaroscuro—contrasting light and dark to model forms convincingly. Leonardo da Vinci's sfumato technique, which blurred edges and transitions between light and shadow, further enhanced the sense of volume. This focus on volume extended to Northern European artists like Jan van Eyck (c.1390–1441), whose oil painting techniques allowed for subtle gradations and a tactile realism in the rendering of skin, fabric, and metal.

The final component to develop was atmosphere, or atmospheric perspective, which involves the portrayal of depth through the softening of colors and reduction of detail in distant objects. This technique was mastered by Leonardo da Vinci and later adopted by landscape painters in the seventeenth-century Netherlands. Artists like Jacob van Ruisdael (c.1629–1682) used atmospheric perspective to convey the vastness of skies and landscapes, enhancing the realism of their scenes. Vermeer also applied subtle atmospheric effects, using the blurring of distant objects and a soft light to create a convincing sense of space and depth in his interiors.

By the seventeenth century, Dutch painters had synthesized these components—outline, form, shadows, relief, overlap, perspective, volume, and atmosphere—into a cohesive approach to realism. The result was an unprecedented level of naturalism that not only depicted the world with accuracy but also imbued ordinary scenes with meaning and emotion. This synthesis represents the apogee of realism in Western art, where technical mastery was matched by a philosophical commitment to portraying the truth of everyday life.

In any case, Realism did not become a dominant pursuit in Muslim art primarily due to religious beliefs that discouraged the depiction of living beings, particularly in a naturalistic manner. The concern stemmed from Islamic teachings that warned against idolatry, with the Hadith containing passages that condemned lifelike images, suggrsting they could lead to the worship of created forms rather than the Creator. This theological stance shifted artistic focus away from realism and towards aniconism—the avoidance of figural imagery in religious contexts.

Instead of pursuing realistic representation, Islamic art developed a distinctive visual language characterized by intricate geometric patterns, arabesques, and calligraphy, emphasizing the infinite and divine nature of God through abstract forms and symmetry. In secular contexts, such as in Persian miniatures or the art of the Mughal Empire, figural representation did occur but was stylized rather than realistic. These images, often flattened and devoid of naturalistic perspective or shadows, prioritized storytelling and decorative qualities over the accurate depiction of space and anatomy. This approach was not due to a lack of technical skill; Muslim artists were highly proficient in using color, pattern, and detailed craftsmanship. However, the philosophical and spiritual priorities of Islamic culture viewed abstraction as a purer means of conveying the divine order and complexity of creation, making realism less relevant to its artistic and spiritual goals.

Vermeer's use of the camera obscura, a device that projected images onto a surface, suggests an almost scientific approach to realism. His manipulation of light and attention to optical effects created scenes that, while idealized in their serenity and order, appeared convincingly real. Similarly, the detailed still lifes of artists like Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606–1684) not only showcased technical prowess but also conveyed vanitas themes, using realism to remind viewers of life's transience.

The reason some cultures with high technical ability, like ancient Egypt or the Byzantine Empire, did not prioritize realism lies in their distinct functions for art. For these cultures, art was a vehicle for spiritual truths, power, and continuity rather than a mirror of the natural world. Realism, in these contexts, was seen as insufficient to convey the eternal and the divine, which demanded stylization, symbolism, and adherence to established conventions.

Realism arguably reached its apogee in the seventeenth-century Netherlands, where the synthesis of observational skill, technical mastery, and a cultural appetite for truth-telling through art created a body of work unmatched in its attention to the visible world. This apogee was not merely technical but philosophical, reflecting a Protestant ethos that valued the moral and spiritual lessons found in the ordinary. The fall from this peak came with the rise of Romanticism and Impressionism in the nineteenth century, movements that, while not dismissing realism entirely, sought to transcend it by exploring subjective perception, emotion, and the fleeting nature of reality.

Many mid-seventeenth century Dutch genre paintings, including those of Vermeer, depicted elegant interiors of the upper middle-class. These pictures reflect concepts that were important in Dutch culture such as the family, privacy and intimacy. However, it is likely that the world of exquisite refinery of Vermeer's compositions did not accurately portray the world he actually observed.

C. Willemijn Fock, a historian of the decorative arts, has demonstrated that floors paved with marble tiles, one of the most ubiquitous features of Dutch interior paintings, were extremely rare in the Dutch seventeenth-century houses. Only in the houses of the very wealthy were floors of this type were occasionally found, although they were usually confined to smaller spaces such as voorhuis (the entrance or corridor) where they would be most likely to be admired by incoming guests. Fock reasons that the abundant representations of these floors in Dutch genre painting may be explained by the fact that "artists were attracted by the challenge involved in representing the difficult perspective of receding multicolored marble tiling."

Vermeer should not be considered a realist painter in the strictest sense of the word. He frequently modified the scale, the shape of objects and even the fall of shadows for compositional or thematic reasons. His scenes, moreover, appear highly staged. One of the most striking examples of this modified reality is a so-called picture-within-a-picture, The Finding of Moses, which appears on the back wall of two of his compositions. In The Astronomer it appears as a small cabinet size picture whereas in the later Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid it appears as an enormous, ebony-framed picture-within-picture. Which one, if either, was true?

Receding and Advancing Colors

Receding and advancing colors refer to the optical effects certain hues create in a composition. Warm colors, such as red, orange, and yellow, tend to appear closer to the viewer, creating a sense of immediacy and prominence—these are known as advancing colors. Cool colors, like blue, green, and violet, tend to recede, giving the illusion of distance and depth. This phenomenon is rooted in human perception and has been widely used by painters to manipulate spatial relationships, enhance realism, and guide the viewer's eye through a composition.

In seventeenth-century Dutch painting, the interplay between receding and advancing colors was a crucial element in creating depth and atmosphere, particularly in interior scenes, still lifes, and landscapes. Many Dutch artists, including Vermeer, exploited this principle to structure their compositions with remarkable subtlety. In his paintings, warm tones often define foreground elements—a red chair or jacket—while cooler blues and grays are used to suggest deeper space, leading the viewer's eye into the scene. This technique is particularly evident in paintings such as The Music Lesson and The Art of Painting, where warm ochres and deep reds anchor the foreground, while cooler tones create a gradual sense of recession.

The same principle was applied in Dutch landscape painting, where artists like Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691) and Jacob van Ruisdael (1628–1682) used aerial perspective to enhance the sensation of spatial depth. In their works, the foreground often features warm earth tones, while the background fades into cooler blues and grays, mimicking the way colors shift in natural light and air. This effect, sometimes called aerial perspective, was a key device in constructing expansive views of the Dutch countryside.

Still-life painters also took advantage of receding and advancing colors to create a convincing illusion of depth. Artists such as Willem Claesz. Heda (1594–1680) and Pieter Claesz (1597–1660) used contrasting warm and cool tones to differentiate objects in their meticulously arranged compositions. A golden lemon peel might spiral forward against a dark, cool-toned pewter dish, emphasizing its form and texture while reinforcing the spatial relationship between objects.

The sophisticated use of receding and advancing colors in seventeenth-century Dutch art was not just a matter of technique but also a means of enhancing realism, visual harmony, and narrative effect. Whether in the quiet luminosity of a Vermeer domestic interior, the vast openness of a Ruisdael sky, or the delicate contrasts of a Claesz still life, Dutch painters demonstrated an acute awareness of how color could be manipulated to shape space and perception.

Reddering

Reddering was a critical term which the Dutch art writer Willem Goeree first used in his Inleyding tot de algemeene teyken-konst in 1668, reflecting his knowledge of Leonardo da Vinci's Traitté de la peinture de Léonard da Vinci (Paris, 1651). Reddering indicates the distribution or arrangement of alternating areas of light and dark in the foreground and background in order to intesify the illusion spatial recession, three-dimensionality as well as to unify composition. Goeree and Gérard de Lairesse (1641–1711) agreed that reddering could be found in nature.

Reflections

Reflection, in its most basic sense, is the phenomenon where light waves bounce off a surface rather than being absorbed or transmitted. This is governed by the Law of Reflection, which states that the angle at which light strikes a surface is equal to the angle at which it is reflected. The clarity and nature of the reflected image depend on the type of surface. Smooth, polished materials such as mirrors or still water produce specular reflections, where light rays remain parallel, creating a clear and undistorted image. Rougher surfaces, like a wooden tabletop or unpolished stone, cause diffuse reflection, scattering light in multiple directions and preventing the formation of a coherent image. In materials like glass or water, internal reflection can occur, leading to more complex optical effects.

Pieter Claesz.

c. 1628

Oil on oak, 35.9 x 59 cm.

Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg

Seventeenth-century Dutch painters demonstrated an extraordinary ability to render reflections, drawing on their acute observation of light's behavior on different materials. The artists of the Dutch Golden Age had no formal scientific understanding of optics in the modern sense, but their meticulous study of the world around them allowed them to depict reflections with remarkable accuracy. Painters such as Vermeer and Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) captured the way light interacts with metal, glass, and polished wood, creating compositions that feel almost photographic in their precision. Vermeer, in particular, was known for his subtle handling of reflected light, whether in the pearlescent glow of a necklace, the reflections on a wine glass, or the soft gleam of a silver pitcher. His painting Woman with a Pearl Necklace includes a mirror on the wall that reflects the young woman in front of it, adding depth and realism to the scene. Similarly, Pieter de Hooch (1629–1684) often depicted silver-stained glass windows that not only allowed light to enter but also cast delicate reflections onto walls and floors.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 45.7 x 40.6 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Mirrors played a special role in Dutch interiors and, by extension, in Dutch painting. Artists depicted convex mirrors that subtly distorted reflections, demonstrating an awareness of how curved surfaces alter light paths. A precursor to this tradition can be seen in Jan van Eyck's (c. 1390–1441) The Arnolfini Portrait where the small convex mirror behind the figures reflects the room with slight warping. This fascination with optical effects carried into the seventeenth century, where painters used mirrors both as compositional devices and as proof of their technical skill. Metal objects, such as the polished brass candlesticks and silver platters seen in still-life paintings, provided another challenge, reflecting distorted views of their surroundings depending on their shape and surface quality.

Water, a central feature of the Dutch landscape, also became an important subject for painters seeking to capture its reflective properties. The many canals and waterways of the Netherlands provided ample opportunity to study the way rippling water distorts reflections. Maritime painters like Willem van de Velde the Younger (1633–1707) captured shimmering reflections of ships on calm waters, while artists like Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691) painted pastoral scenes where reflections in rivers subtly reinforced the tranquil atmosphere.

It has been suggested that Dutch painters surpassed Italians in their ability to render reflections, though locating a definitive historical source for this claim remains difficult. The Dutch emphasis on realism and the depiction of light set them apart from their Italian counterparts, who were often more concerned with idealized forms and dramatic chiaroscuro. The Dutch tradition, with its focus on capturing everyday life in minute detail, naturally led to a heightened awareness of optical effects, including reflections. This sensitivity to light and materiality remains one of the defining characteristics of Dutch Golden Age painting, making their works feel both scientifically precise and visually poetic.

Relining

From: Wikipedia.

The relining, or lining as it is also called, of a painting is a process of restoration used to strengthen, flatten or consolidate oil or tempera paintings on canvas by attaching a new canvas to the back of the existing one. In cases of extreme decay, the original canvas may be completely removed and replaced. Lining has been very widely practiced, and during the nineteenth century, some painters had their works lined immediately after, or sometimes even before, completion. There have been some doubts concerning its benefits more recently, especially since the Greenwich Comparative Lining Conference of 1974.

The procedure as carried out in the nineteenth century is described by Theodore Henry Fielding in his Knowledge and Restoration of Old Paintings (1847). The picture was removed from the stretcher and laid on a flat surface. The edges of the canvas were trimmed, leaving the original support smaller than the new lining. A sheet of paper covered in thin paste was laid on the surface of the painting, which was then placed face-down on a board or table. The back of the picture was then coated with paste, copal varnish, or a glue made from cheese. The new lining canvas was pressed down onto the back of the picture by hand; then the outer edges of the lining cloth were fastened to the table by means of a large number of tacks, and a piece of wood with a rounded edge was passed over the back of the cloth, to ensure perfect adhesion. When the glue had dried sufficiently, the lining was smoothed with a moderately hot iron. Fielding cautions that "the greatest care must be taken that the hand does not stop for an instant, or the mark of the iron will be so impressed on the painting, that nothing can obliterate it." The picture was then nailed to a new stretcher, and the paper was washed off with a sponge and cold water.

Fielding also describes the process for the complete removal and replacement of the canvas. In this, the picture was covered with paper, as if for lining, then fastened to a board or table, after which the old cloth was rubbed away with a small rasp with very fine teeth; when the restorer had gone "as far as may be prudent," the remainder of the cloth could be taken off with a pumice stone, until the ground on which the picture was painted became visible. It was then ready to receive its new cloth, which had previously been covered with copal varnish, glue, or paste. In this procedure, the hot iron was not used.

The use of hand-ironing is liable to produce a flattening of impasto, referred to as crushed impasto. This problem was mitigated by the introduction in the 1950s of vacuum hot-table processes, designed for use with wax-resin adhesives, which exerted a more even pressure on the paint surface; however the longer periods of heating and high temperatures involved often led to other types of textural alteration.

Wax-based adhesives seem to have been in use for lining from the eighteenth century, although the earliest well-documented case of their employment is in the lining of Rembrandt's Night Watch in 1851. Although, initially, pure beeswax was used, mixtures incorporating resins such as dammar and mastic, or balsams such as Venice turpentine, were soon found preferable. During the twentieth century, it came to be realized that the impregnation of the paint layer with wax could have deleterious effects, including darkening of the picture, especially where canvas or ground were exposed.

Although experiments with synthetic fabrics were carried out during the 1960s and 1970s, traditional linen cloths are still usually used for lining. However polyester canvas is often used for strip-lining, where only the edges of the painting are backed, and for loose-lining, in which no adhesive is used. This latter technique helps protect the painting from atmospheric pollution, but does not flatten or consolidate the paint surface.

All of Vermeer's canvases, except for The Guitar Player, have been relined, and one, The Lacemaker, mounted on panel. Not only has The Guitar Player never been relined, it is still mounted on its original wood stretcher with wooden pegs, making it an extraordinary rarity among paintings of the age.

Renaissance

The French word from which Renaissance is derived is renaissance itself, meaning "rebirth" or "revival." It comes from the verb renaître (to be reborn), which is formed from naître (to be born). The term was popularized by nineteenth-century French historians such as Jules Michelet, who used it to describe the revival of art, science, and culture in Europe following the Middle Ages. In both French and English, Renaissance is capitalized when referring to the historical period.For Italy the period is popularly accepted as running from the second generation of the fourteenth century to the second or third generation of the sixteenth century.

Characteristic of the Renaissance is the steady rise of painting and of the other visual arts that began in Italy with Cimabue (c. 1240–1302), and Giotto (1266–1337) and reached its climax in the sixteenth century. An early expression of the increasing prestige of the visual arts is found on the Campanie of Florence, where painting, sculpture and architecture appear as a separate group between the liberal and the mechanical arts. What characterizes the period is not only the quality of the works of art but also the close links that were established between the visual arts, the sciences and literature.

Renaissance, in the broadest sense, refers to the period of artistic, intellectual, and cultural renewal that emerged in Europe between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries, inspired by a revival of Classical antiquity. The term, meaning "rebirth," reflects the rediscovery of ancient texts, artistic principles, and scientific inquiry that shaped new approaches to humanism, naturalism, and perspective in art. Artists moved away from the rigid, hieratic styles of the Middle Ages and developed techniques that emphasized depth, proportion, and the accurate depiction of the human figure and the natural world. While the Renaissance is often considered a unified movement, it evolved in distinct phases, each with its own artistic Andrea del Verrocchio (c. 1435–1488) holds a crucial place in the development of the Italian Renaissance, especially in Florence during the second half of the fifteenth century. Though not always granted the same level of fame as some of his contemporaries, his significance lies in his role as both a masterful artist and a profoundly influential teacher. His workshop was one of the most important artistic centers of its time and served as a formative training ground for some of the greatest figures of the High Renaissance, most notably Leonardo da Vinci.characteristics and regional developments.

The Early Renaissance, spanning roughly from the late fourteenth to the early fifteenth century, saw the foundational innovations that defined the period. Florence, under the patronage of families like the Medici, became the center of artistic experimentation. Artists such as Giotto di Bondone (c. 1267–1337) pioneered a more naturalistic approach to space and form, while later figures like Masaccio (1401–1428) developed linear perspective, giving paintings a convincing sense of depth. Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) applied mathematical precision to architecture, as seen in the dome of Florence Cathedral, while sculptors such as Donatello (c. 1386–1466) revived classical ideals in their treatment of the human form.

Verrocchio's own style represents a transitional moment between the Early Renaissance, characterized by clarity, balance, and careful observation, and the emerging interest in expressive dynamism and psychological complexity. His work in sculpture—such as the bronze David or the Equestrian Monument to Bartolomeo Colleoni in Venice—shows a technical sophistication and understanding of anatomy and movement that strongly influenced later artists. His David, for instance, reflects a more lifelike and introspective approach compared to Donatello's earlier version, suggesting a shift toward the Renaissance's growing emphasis on the individual.

Andrea del Verrocchio and Lorenzo di Credi

c. 1475–1486

Oil on panel, 196 x 196 cm

Cathedral of San Zeno, Pistoia

The High Renaissance, flourishing in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, marked the peak of Renaissance artistic achievement. Artists perfected techniques of linear perspective, composition, and anatomical accuracy, producing works of harmony and idealized beauty. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) embodied the Renaissance Man, mastering painting, anatomy, engineering, and scientific observation. His Mona Lisa and The Last Supper demonstrate his skill in sfumato, a technique that created soft, atmospheric transitions of light and shadow. Michelangelo (1475–1564) sculpted the monumental David and painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling, showcasing his deep understanding of the human body and dynamic composition. Raphael (1483–1520) excelled in balanced, serene compositions, as seen in The School of Athens, where he harmonized Classical themes with Renaissance ideals of knowledge and artistic mastery.

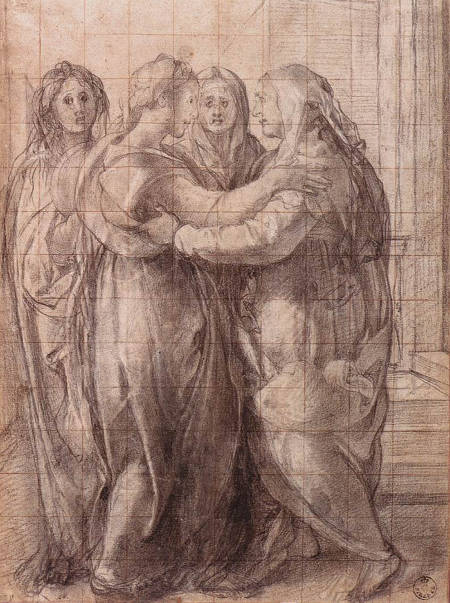

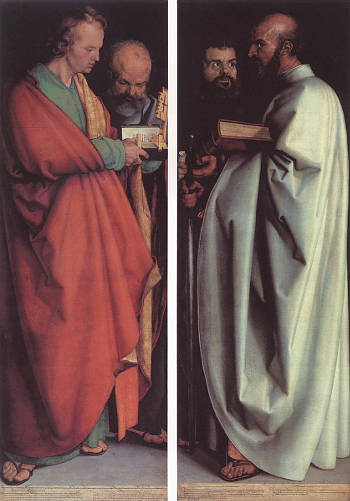

The Late Renaissance, or Mannerism, emerged in the mid-sixteenth century as a reaction to the balance and clarity of the High Renaissance. Artists such as Jacopo Pontormo (1494–1557) and Parmigianino (1503–1540) experimented with elongated figures, unnatural spatial arrangements, and intense colors. Mannerist painters moved away from strict naturalism, emphasizing expressive distortion and complex compositions. This period also saw the expansion of Renaissance ideas into northern Europe, where artists such as Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Hans Holbein the Younger (c. 1497–1543) combined Italian techniques with the meticulous detail characteristic of Northern traditions.

The Northern Renaissance developed concurrently but with distinct characteristics, particularly in the Low Countries and Germany. While Italian artists focused on idealized human forms and classical references, Northern artists emphasized intricate detail, precise textures, and a deep interest in everyday life. Jan van Eyck (c. 1390–1441) mastered oil painting, achieving an unprecedented level of realism, as seen in the Arnolfini Portrait. Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450–1516) created fantastical, allegorical scenes filled with moral and religious symbolism, while Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525–1569) explored peasant life with remarkable observational skill. Unlike the monumental frescoes of Italy, Northern artists often worked on smaller, highly detailed panels that catered to a growing middle-class market.

By the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, Renaissance ideals gave way to the Baroque, a period of heightened drama, movement, and emotional intensity. While the transition was gradual, the shift from harmonious balance to theatrical dynamism is evident in the works of Caravaggio (1571–1610) and Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640). In the Netherlands, the Renaissance had a more muted impact than in Italy, largely due to the pragmatic and Protestant culture of the Dutch Republic. However, early Dutch painters such as Jan Gossaert (c. 1478–1532) and Maarten van Heemskerck (1498–1574) introduced Italianate influences, paving the way for later developments in Dutch art.

Jan Gossaert

1510–1515

Oil on oak, 177.2 x 161.8 cm

National Gallery, London

In seventeenth-century Dutch painting, Renaissance principles persisted but were adapted to suit the tastes and intellectual climate of the Dutch Republic. The emphasis on perspective, naturalism, and Classical themes can be seen in history painting and architectural studies, while the empirical realism of Dutch artists reflected a departure from the idealized forms of the High Renaissance. Vermeer's mastery of perspective and light suggests an awareness of Renaissance spatial construction, yet his intimate, meticulously detailed interiors represent a distinctly Dutch evolution of these principles. The Renaissance thus laid the foundation for the innovations of the Dutch Golden Age, demonstrating how artistic ideas were continually reinterpreted to align with changing cultural and intellectual contexts.

The period of the Renaissance brought with it fundamental changes in the social and cultural position of the artist. Over the course of the period there is a steady rise in the status of the painter, sculptor and architect and a growing sympathy expressed for the visual arts. Painters and sculptors made a concerted effort to extricate themselves from their medieval heritage and to distinguish themselves from mere craftsmen. At the beginning of the Renaissance, painters and sculptors were still regarded as members of the artisan class, and occupied a low rung on the social ladder. A shift begins to occur in the fourteenth century when painting, sculpture and architecture began to form a group separate from the mechanical arts. In the fifteenth century, the training of a painter was expected to include knowledge of mathematical perspective, optics, geometry and anatomy.

Although the influence of the Italian Renaissance was felt throughout Europe and in the Netherlands as well, it is interesting to note that none of the great masters of Dutch painting felt the necessity to go to Italy to adsorb its lessons first hand. Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1629–1682), Frans Hals (c. 1582–1666), Vermeer and Rembrandt (1606–1669) all stayed in the Holland, close to their own culture.

Render

Rendering in art and technical drawing means the process of formulating, adding color, shading and texturing of an image. It can also be used to describe the quality of execution of that process. When used as a means of expression, it is synonymous with illustrating. The alternative method to rendering an image is capturing an image such as photography or image scanning. Both rendered and captured images can be mixed, edited, or both.

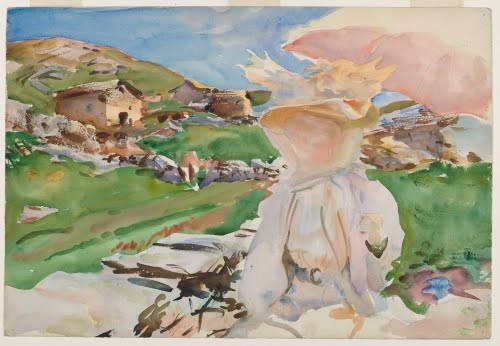

Repoussoir

Repoussoir, f rom the French verb meaning to "push back," is one of the pictorial means of achieving perspective or spatial contrasts by the use of illusionistic devices such as the placement of a large figure or object in the immediate foreground of a painting to increase the illusion of depth in the rest of the picture. Caravaggio (1571–1610) had become famous for his paintings of ordinary people or even religious subjects in compositions. Repoussoir figures appear frequently in Dutch figure painting where they function as a major force in establishing the spatial depth that is characteristic of painting of the seventeenth century. Landscapists too learned to exploit the dramatic effect of repoussoir to enliven their depictions of the flat uneventful Dutch countryside. Repoussoir formulae is still used in landscape painting and is influential in photography as well.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

1601

Oil on canvas, 141 x 196.2 cm.

National Gallery, London

Vermeer adapted various examples of repoussoir to his own compositions that he had derived from other Dutch paintings. The looming figure of the officer in Officer and Laughing Girl is very similar in color and shape to the repoussoir figure in The Procuress by Gerrit Van Honthorst (1592–1656).

The most spectacular example of repoussoir in Vermeer's oeuvre may be found in The Art of Painting. The large foreground curtain on the left-hand side of the painting seems to have been just drawn back to let the viewer enter the pictorial space. Both the curtain's warm tone and the heavy impasto paint application makes it appear even nearer to the viewer.

This kind of repoussoir was generally placed on the left-hand side of the composition because we tend to rapidly scan images darting from the left to the right as when reading. By consequence, Vermeer's repoussoir is suited to be looked at by the reading eye, which, after a brief moment's delay at the repoussoir, is directed toward the key moment of the representation of the painter and his model and explores the rest of the painting thereafter.

Representation

In art, representation refers to the depiction of subjects in a way that conveys their appearance, meaning, or essence, whether through direct imitation or symbolic abstraction. It is one of the fundamental modes of artistic expression, encompassing a wide range of approaches from naturalistic portraiture to highly stylized or conceptual interpretations. Unlike purely abstract art, which does not attempt to depict recognizable forms, representation engages with the visible world, human figures, objects, landscapes, or narratives, often reflecting the cultural, historical, and philosophical context in which it was created.

Throughout history, representation in art has evolved significantly. In ancient civilizations, artistic representation was often governed by strict conventions. Egyptian art, for example, used a hierarchical scale to indicate social status, depicting pharaohs larger than other figures, while Greek sculpture sought to capture the idealized human form, progressing from the rigid Archaic kouros figures to the dynamic realism of Classical and Hellenistic statues.

During the Renaissance, representation became increasingly grounded in scientific observation and perspective, with artists such as Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Raphael (1483–1520) employing techniques like linear perspective, foreshortening, and chiaroscuro to create the illusion of three-dimensional space. This period saw a deep engagement with human anatomy, proportion, and the natural world, as artists sought to render figures with heightened realism and psychological depth.

In the Baroque era, representation became more theatrical and emotionally charged, with artists like Caravaggio (1571–1610) using dramatic lighting and intense realism to enhance narrative impact. Rembrandt (1606–1669), through his penetrating self-portraits and biblical scenes, captured psychological complexity, demonstrating that representation could go beyond physical likeness to convey inner emotion and meaning.

Reproduction (of artworks)

In painting and art history, the term reproduction refers to copies of original artworks created through various medium, ranging from hand-painted replicas to mechanical or digital printing. The concept of reproduction has been central to the dissemination, study, and commercialization of art for centuries, influencing how people engage with masterpieces beyond their original locations.

Historically, reproductions were often made by workshop assistants or followers of a master, sometimes under direct supervision, as a means of training or spreading an artist's distinctive style. With the advent of printmaking techniques such as engraving, etching, and lithography, reproductions allowed wider audiences to experience and study famous works that would otherwise be inaccessible. These prints played a significant role in shaping art appreciation and scholarship, particularly before the advent of photography.

In modern times, printed reproductions can take many forms, from high-quality museum-sanctioned facsimiles to inexpensive posters. Digital technologies now allow for astonishingly precise reproductions, capturing even the subtlest textures and color nuances. Some contemporary reproductions, such as giclée prints, use fine-art inkjet printing on canvas or paper, mimicking the original's txetural qualities.

While reproductions make art more accessible, they also raise questions about authenticity and value. Unlike original works, which bear the artist's hand and historical presence, reproductions lack provenance and uniqueness. However, some reproductions, such as those created for conservation purposes, play a crucial role in preserving cultural heritage. For instance, in cases where an artwork is at risk of deterioration, an exact reproduction can allow museums to display a faithful likeness while protecting the original.

Reproductions, therefore, occupy a complex space in art history, bridging the gap between accessibility and authenticity, scholarship and commerce, preservation and originality.

Reputation

Reputation, in the context of artists, refers to the perception of their skill, innovation, and character within the artistic community and among patrons, collectors, and critics. It is shaped by a combination of factors, including the artist's technical ability, subject matter, association with influential figures, and market demand for their work. Reputation could be carefully cultivated, rise or fall due to external circumstances, or be reassessed long after an artist's death.

In the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic, an artist's reputation played a crucial role in securing commissions, maintaining a steady income, and influencing the reception of their work. Unlike in Italy or France, where patronage was often tied to the court or the church, Dutch artists operated in a relatively open market where reputation was built through skill, networking, and sometimes strategic self-promotion. Guild membership, particularly in the Guild of St. Luke, helped establish professional credibility, while the endorsement of prominent collectors or connoisseurs could elevate an artist's status.

For many painters, reputation was tied to specialization. The Dutch art market favored artists who excelled in specific genres—whether portraiture, landscape, still life, or history painting. Painters such as Frans Hals (1582–1666) gained a reputation for lively and expressive portraiture, while Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1628–1682) was admired for his evocative landscapes. Specialization was not only an artistic choice but also a marketing strategy, helping artists distinguish themselves in a highly competitive environment.

Reputation was also affected by associations with prominent figures. Artists linked to influential patrons, such as Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), could gain recognition beyond their immediate circle. Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), for example, initially built his reputation in Leiden but achieved greater renown after moving to Amsterdam and receiving commissions from wealthy burghers and civic institutions. However, reputation was volatile, and Rembrandt's financial struggles and changing tastes later led to a decline in his standing.

Art manuals and biographies played a role in shaping reputation, both during an artist's lifetime and posthumously. Karel van Mander (1548–1606) in Het Schilder-Boeck (1604) helped construct the reputations of past and contemporary painters by emphasizing their artistic lineage and personal virtues. Later, Arnold Houbraken (1660–1719) in De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (1718–1721) created a hierarchy of Dutch painters, reinforcing certain reputations while diminishing others.

The international reception of Dutch painters further influenced reputation. Artists whose works were collected by foreign courts, such as Gerrit Dou (1613–1675) and Jan Steen (1626–1679), gained prestige beyond the Netherlands, often commanding higher prices abroad than at home. In contrast, artists who remained within the domestic market might have a strong regional reputation but limited international recognition.

Reputation could also be shaped by scandal or personal conduct. Artists known for extravagant lifestyles or unorthodox behavior, such as Jan Steen, were sometimes viewed with skepticism despite their technical skill. Conversely, painters like Gerard ter Borch (1617–1681), known for refinement and diplomatic engagements, maintained a more dignified reputation, reinforcing their appeal to elite patrons.

Over time, reputation was subject to historical reevaluation. Some painters who were immensely successful in their lifetime, such as Bartholomeus van der Helst (1613–1670), later fell into relative obscurity, while others, like Vermeer, who was relatively unknown in his time, were rediscovered and gained posthumous acclaim.

Reserve

Attributed to Gonzales Coques (Flemish, Antwerp 1614/18–1684 Antwerp)

c. 1640s

Oil on panel, 55.9 × 44.1 cm.

Orsay Collection

A reserve is a temporarily unfinished or blank area of a painting which is surrounded by painted areas that are either partially or fully completed. A reserve generally corresponds to the area within the outer-most contour of a single object such as a figure, a tree or an architectural feature. Once painters of the Renaissance and Baroque had established the composition through a thin outline drawing on a monochrome ground, it was then underpainted with a dull monochrome tint. Successively, each area of the composition was worked up in a piecemeal fashion with full color, creating reserves of unpainted objects.

Period art manuals recommended that the background areas, usually the least important from a thematic point of view, be painted first, leaving reserves for the important foreground elements. This sequential system would allow to the painter to softly blend the outer contours of the foreground figures into the colors of the background, slightly overlapping them and creating a more convincing sensation of roundness. However, this system was not applied dogmatically and one can find examples of unfinished paintings which show the figures worked up in color with the background left relatively unfinished. Portrait painters routinely completed the face before working up the background or the figure's body.

Resin

A resin is a solid or highly viscous substance of plant or synthetic origin. Many plants, particularly woody plants, produce resin in response to injury. Resin acts as a bandage protecting the plant from invading insects and pathogens. Plant resins are valued for the production of varnishes, adhesives and food glazing and paint mediums. The hard transparent resins, such as the copals, dammars, mastic and sandarac, are principally used for varnishes and adhesives, while the softer odoriferous oleo-resins (frankincense, elemi, turpentine, copaiba), and gum resins are more used for therapeutic purposes and incense.

Resins are used to increase the gloss of oil paint, reduce the color and drying time of a medium, and add body to drying oils. The most commonly used is a natural resin known as dammar, which should be mixed with turpentine as it will not thoroughly dissolve when mixed with mineral spirits. Dammar can also be used as a varnish. Exudations from conifer resins used in painting are Strasbourg turpentine, Venice turpentine, sandarac and various kinds of copals.

Restoration (vs conservation)

Restoration and conservation are two distinct approaches to preserving artworks, buildings, and cultural artifacts, differing in both philosophy and method. Restoration aims to return an object to a previous state, often attempting to recreate its original appearance by removing later additions, repainting missing areas, or reconstructing damaged elements. This approach prioritizes aesthetic unity and historical accuracy, sometimes requiring significant intervention that alters the object's current state. Conservation, in contrast, focuses on preserving an artifact as it exists today, preventing further deterioration while maintaining as much of the original material as possible. Conservation methods typically include cleaning, stabilizing structures, and applying protective treatments, always with the principle of minimal intervention in mind. While restoration seeks to recover a lost past, conservation prioritizes long-term preservation, often leaving signs of age and history intact. In modern museum and heritage practices, conservation is generally preferred, as it respects an object's authenticity and avoids irreversible changes.

Retouching

On 23 September 1971, a 21-year old idealist thief stole Vermeer's Love Letter (c. 1669), which hung on loan in the Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels. For easy transportation underneath his sweater, the thief roughly cut the painting on canvas from its stretcher, folded it once and tucked it in his trousers. When the painting was recovered two weeks after the theft, it was badly damaged and nned of both conservation and retoucing in larges areas where the original paint had become detached.

Retouching describes the work done by a restorer to replace areas of loss or damage in a painting. Retouchings are done in a soluble medium that differs from the original so that they can be removed easily. Retouching is usually intended to be invisible to the naked eye, but there may be reasons for it to be distinguishable when the painting is viewed at close range.

Over the period of 250 years after Vermeer's paintings left the artist's studio, a number have been retouched, some only to repair paint damage or fading, while at least one, features a compositional addition that does not reflect the artist's original intentions. On the background wall of Girl Interrupted in her Music a small birdcage, a common prop in Dutch interior painting, was added by a later hand. A violin once hung on the background of same picture, most likely itself another later addition.

Retrospective

A retrospective, in the broadest sense, refers to a reflective look back at past events, works, or achievements, often to assess their significance or development over time. It is commonly used in various fields, including literature, film, and history, but in art, a retrospective specifically refers to an exhibition or study that presents a comprehensive overview of an artist's body of work, often spanning their entire career.

Retrospectives are typically organized by museums, galleries, or academic institutions to showcase how an artist's style, technique, and thematic concerns evolved over time. Unlike standard exhibitions, which may focus on a particular theme, movement, or period, a retrospective aims to provide a deeper understanding of an artist's artistic progression, influences, and impact. Major retrospectives often coincide with key anniversaries, such as the centenary of an artist's birth or after their passing, serving both as an honor and a scholarly examination.

The concept of the retrospective became more formalized in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, particularly with the rise of public museums and art institutions that sought to document and historicize artistic achievements. The Salon des Refusés (1863), which showcased rejected works from the official French Salon, can be seen as an early precursor to the idea of looking back at artists who were overlooked in their time. By the late nineteenth century, retrospectives of figures such as Francisco Goya (1746–1828) and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) helped redefine their legacies.

In the seventeenth-century Netherlands, there was no institutionalized retrospective tradition as we understand it today. However, artists were sometimes honored with collections of their prints or drawings, and art dealers or collectors might organize posthumous sales or exhibitions of an artist's works. For instance, after Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) died in relative obscurity, interest in his work revived in later decades, leading collectors to seek out and reassess his paintings and etchings. Though not "retrospectives" in the modern sense, these sales and re-evaluations played a similar role in shaping an artist's posthumous reputation.

Today, retrospectives serve both academic and public audiences, offering insight into an artist's creative evolution, historical significance, and ongoing influence. They often recontextualize overlooked or misunderstood works, sometimes challenging previous interpretations of an artist's career. In some cases, they even lead to new discoveries, such as reattributions, conservation findings, or fresh scholarly perspectives that alter how an artist is viewed within the borader perspective ofm art history.

In 2023, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam hosted a landmark retrospective of Johannes Vermeer, marking the most comprehensive exhibition of the Dutch master's work to date. Running from February 10 to June 4, the exhibition featured 28 of Vermeer's approximately 35 known paintings, an unprecedented assembly that drew art enthusiasts from around the globe. Notably, it included works never before displayed in the Netherlands, like the newly restored Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window from the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden.

The retrospective was organized in collaboration with the Mauritshuis and involved extensive research into Vermeer's artistry, techniques, and creative process. This scholarly effort provided fresh insights into his work, enhancing the exhibition's depth and educational value.

The exhibition attracted approximately 650,000 visitors, setting a new attendance record for the Rijksmuseum. To accommodate the overwhelming demand, the museum extended its opening hours and offered additional tickets, underscoring Vermeer's enduring appeal and the exhibition's significance in the art world.

Rhythm

In art, rhythm refers to the visual flow and movement created by repeating elements, patterns, or structures within a composition. Just as rhythm in music organizes sound through repetition and variation, visual rhythm in painting, sculpture, and design guides the viewer's eye across a work of art , creating a sense of harmony, energy, or dynamism. Artists achieve rhythm through the strategic use of line, shape, color, light, and spatial arrangement, often balancing repetition with variation to maintain both unity and interest.

Throughout history, rhythm has played a fundamental role in artistic composition. In Classical and Renaissance art, rhythm was often tied to mathematical proportions and symmetry, creating a sense of balance and idealized beauty. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Raphael (1483–1520) used rhythmic arrangements of figures and architectural elements to structure their compositions. The repetition of curved forms, balanced poses, and draped garments in works such as Raphael's The School of Athens (1509–1511) establishes a flowing, harmonious movement that directs the viewer's gaze through the scene.

In Baroque painting, rhythm took on a more dynamic and dramatic quality. Artists like Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and Caravaggio (1571–1610) used diagonal compositions, sweeping gestures, and contrasts of light and shadow to create a sense of movement and tension. Rubens, in particular, excelled at rhythmic compositions in his large-scale history paintings, where twisting figures and billowing drapery generate an almost musical interplay of motion.

Claude Monet

1910s

Oil on canvas, 150 x 197 cm.

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

In Impressionism, rhythm became less about structured repetition and more about the pulsation of light and color. Claude Monet (1840–1926) and Edgar Degas (1834–1917) applied rhythmic brushstrokes and fragmented light to evoke the fleeting nature of time and movement. In Monet's Water Lilies series, the repetition of soft, rippling brushstrokes across the surface of the pond creates a rhythmic, meditative effect, while Degas' ballet dancers, often shown in staggered, repeated poses, suggest a rhythmic unfolding of motion.

Modernist movements took rhythm in new directions, emphasizing abstraction and non-representational structures. Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), in his grid-based De Stijl compositions, used rhythmic placement of colors and lines to create a visual equivalent of musical harmony, inspired by jazz and Theosophical ideas of balance. Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), in his drip paintings, developed a highly energetic, all-over rhythm where lines of paint seem to pulse and vibrate across the canvas, creating a chaotic yet cohesive motion.

In contemporary and digital art, rhythm continues to be a defining compositional element, often interacting with technology and motion-based media. Digital animation, kinetic sculptures, and even interactive installations rely on rhythm to structure the viewer's experience, reinforcing the timeless role of repetition, pattern, and movement in visual storytelling.

Whether creating a sense of calm and order through measured repetition or conveying energy and chaos through irregular patterns, rhythm remains a fundamental principle in artistic composition. It directs the viewer's eye, establishes unity, and enhances the emotional impact of an artwork, making it one of the essential tools in the visual language of art.

Rigger Brush

A rigger brush is a specialized type of paintbrush characterized by long, thin bristles tapering to a fine point. Its distinctive shape allows it to hold a generous amount of paint while producing continuous, precise lines without frequent reloading.

This brush received its name from its original purpose in marine painting, where it was commonly employed to depict the intricate rigging of sailing vessels. The rigger's thin, elongated bristles facilitate drawing consistent, delicate, and extended strokes, ideal for rendering the numerous fine ropes and cables seen in ship scenes. When used together with a mahlstick—which supported and guided the painter's hand—the rigger brush allowed artists to accurately and steadily paint the detailed rigging characteristic of maritime imagery.

Rough and Smooth Styles

Years before Frans Hals (c. 1582–1666) developed his characteristic free handling of paint, Gerrit Dou (1613–1675) specialized incredibly meticulous brushwork, Dutch artists and art lovers already distinguished between two main painting styles: ruwe or rauw, ("rough") and nette, fijn, or gladde ("clean," "fine" or "smooth"). The rough style was also associated with the loss'e style ("loose").

Rembrandt van Rijn

1654

Oil on canvas, 112 x 102 cm.

Six Collection, Amsterdam

The rough and smooth styles, codified in Dutch art theory, refers to two contrasting approaches to painting texture and detail. The rough style, exemplified by artists like Frans Hals (c.1582–1666), used loose, visible brushstrokes to convey a sense of spontaneity and life, often prioritizing the overall impression over meticulous detail. In contrast, the smooth style involved finely blended, almost invisible brushwork to achieve a polished, detailed surface, as seen in the works of Gerrit Dou (1613–1675) and other fijnschilders, creating an illusion of reality through precise textures and subtle lighting.

Dou, Rembrandt's first pupil, developed, or rather, brought the fine style to full fruition in the 1630s. Smooth painters went to incredible lengths to achieve the perfect, polished illusion of reality. The time Dou spent on his minutely detailed works is legendary: according to some of his contemporaries it took him days to paint a tiny broom the size of a fingernail. It is said that by sitting down quietly in his studio an hour before he began to paint, Dou was able to defeat one of the mortal natural enemies of the smooth style; dust.

Fine painting, which gave rise to the modern term fijnschilder (Dutch: fine painter) was a practiced in Leiden. In their own time, however, a fijnschilder, or "fine painter," was simply someone who could make a living through art and was distinguished from a kladscilder ("house painter"), both of whom were enrolled in the Saint Luke Guild. Today, art historians adopt the term fijnschilder to define a group of painters who worked in Leiden: Gerrit Dou, Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667), Pieter Cornelisz. van Slingelandt (1640–1691), Frans van Mieris (1635–1681) and Adriaen van der Werff (1659–722). However, the school only came into its own after Gabriel Metsu's (1629–1667), one of the best practitioners of the smooth style, had moved. It is most likely that fijnschilders worked at least partially naer het leven (from life).

In 1604, Karel van Mander (1548–1606), the Dutch painter and art theoretician who first codified the rough and smooth manners, advised artists always to start by learning the smooth manner, which was considered easier, and only subsequently choose between smooth and rough painting. A later Dutch art theoretician, Gérard de Lairesse (1641–1711) wrote:

…he who practices the former [smooth] manner, has this advantage above the other, that being accustomed to neatness, he can easily execute the bold and light manner, it being the other way difficult to bring the hand to neat painting; the reason of which is, that, not being used to consider and imitate the details of small objects, he must therefore be a stranger to it; besides, it is more easy to leave out some things which we are masters of than to add others which we have not studied, and therefore it must be the artist's care to learn to finish his work as much as possible.

"The smooth manner of painting had been associated with descriptive tasks, for example flower painting or animal painting, well before the successes of the Leiden school, and in many parts of Europe. But the Dutch had made a specialty of it. Karl van Mander… linked the modern smooth manner of the legendary mysteries of Jan van Eyck's (before c. 1390–1441) technique. Even Van Eyck's underpainting was 'cleaner and sharper' [suyverder en scherper] than the finished work of other painters.'"Christopher S. Wood, "'Curious Pictures' and the art of description," Word & Image 11, no. 4 (1995): 332.

The question remains whether the smooth manner is truly more suited to evoke the illusion of reality than the rough manner is difficult to answer. While it is true that the smooth manner captures texture, form and detail with incredible efficacy, the rough manner, practiced by great artists like Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), Rembrandt (1606–1669) or Titian (c. 1488/1490–1576), is capable of evoking a sense of lifelikeness and naturalness that makes even the reality represented in the best smooth painting look frozen and artificial. To best appreciate the two styles, it was recommended that art lovers adjust their viewing distance: farther away for a roughly painted work, close up for a finely executed one.

It is believed that the rough manner stimulates the activity of the eye far more powerfully than painting with a smooth surface. The unequivocally completed, clear and polished work of art tends to exclude the spectator from participating in the picture. The roughly finished painting demands an intellectual response from the beholder because the painter of the rough manner deliberately exposes the working processes to the spectator making him party to the artifice by which the illusion is achieved. The smooth painter, instead, deliberately conceals his manner and isolates the viewer from the picture making process, which may, is some subjects give rise to a sensation of deception. The rough painter, instead, hides nothing, and is registered as more sincere, or at least to modern sensibilities.

Both of these great artists "were working against the prevailing norms of smooth or fine painting, and, for both, the example of late Titian was cited as authorization of their increasingly broken and irregular handling of paint. In a remarkable trajectory that echoed Titian's, Rembrandt moved through his career from being a founding father of the Leiden fijnschilders...—those painters who, with invisible brushstrokes and 'the patience of saints and the industry of ants' (as one contemporary author described it), took the illusionistic depiction of objects to a new level—to his culmination as the undisputed extreme exponent of the rough manner. In his late works, the paint surfaces have the density of rock faces. It is thought that Rembrandt's rough manner may have been a factor contributing to his personal financial troubles in later life.

"The rough manner in Dutch painting was a conscious aesthetic choice and was described in Rembrandt's day as lossigheydt, 'looseness'—the equivalent of the sprezzatura of the Italian writer Baldesar Castiglione (1478–1529), who drew parallels between the effortless nonchalance of courtly behavior and the loose, seemingly careless touches that the artist applied with his brush. The epitome of lossigheydt or sprezzatura in Rembrandt's art is his masterpiece, the Portrait of Jan Six, in which the paint seems to have massed spontaneously into the gorgeous fabric of the sitter's clothes and the powerful passages of his face and hands. Seventeenth-century Spanish art theory, similarly, had terminology for loose, expressive brushstrokes: they were referred to as borrones or manchas, words loaded with the same significance as 'sprezzatura.'"David Bomford, "Rough Manners: Reflections on Courbet and Seventeenth-Century Painting," in papers from the Symposium Looking at the Landscapes: Courbet and Modernism, J. Paul Getty Museum, March 18, 2006, 10, https://www.getty.edu/publications/resources/virtuallibrary/0892369272.pdf.

"Seventeenth-century painters and art lovers had terms to describe the notable changes in painterly technique and compositional method that accompanied the 'gentrification' of Vermeer's work in the 1660s. Whereas the relatively grainy texture of bread, carpets and bricks in the early words would have been seen as rouw or rough, the even, polished facture of the Girl with a Wine Glass or Woman Holding a Balance was explicitly net, neat or smooth. By his increasing commitment to the smooth style, Vermeer essentially sided with the manner that was gaining market and connoisseur favor after mid-century. However different his paintings look from the miniaturist neatness of Dou, Frans van Mieris (1635–1681), and Gerrit ter Borch (1617–1681), they, too, must have been admired especially in the decade that saw a lesser interest in the rough painting associated with Rembrandt and his students and followers. The smooth manner typically went along with more genteel and elegant themes. The rough brothel scenes of the 1620s and 1630s, so often painted with Caravaggesque uncouthness, now became sublimated in more slyly humorous paintings in the neat style."Mariët Westermann, "Vermeer and the Interior Imagination," in Vermeer and the Dutch Interior, ed. Alejandro Vergara (Madrid: Museo Nacional de Prado, 2003), 231.

Rounding / Relief

Pietro Lorenzetti

c. 14th century

Tempera on panel

Diocesan Museum, Pienza