Subject Matter in Dutch Painting, Training, Technique and Commerce

The rise of open art markets in the Netherlands transformed the European art trade. Originating from medieval trade systems, these markets thrived due to social and economic changes, attracting a more diverse range of consumers. This shift led to new demands and tastes, different from traditional ecclesiastical and noble patronage. Artists responded by diversifying their work, exploring new subjects, materials, and formats. This period saw increased specialization, collaboration, and the rise of professional art dealers who facilitated sales and influenced art trends. Art guilds adapted regulations to these changes, ensuring quality control and member protection. This transformation was a localized phenomenon, influenced by international commerce and urban-specific conditions, and has been extensively studied by economic historians of art.

In addition to being a site of labor, the artist’s workshop was also an engine of entrepreneurship connected to the changing market. Although they practiced their craftsmanship within the confines of traditions, artists also reimagined and reinvented their businesses, responding to two main impetuses. On the one hand, artists experimented and took risks to identify subjects and invent products that were saleable. On the other hand, they sought to produce work in new ways and with greater efficiency.Elizabeth Alice Honig, Jessica Stevenson Stewart, and Yanzhang (Tony) Cui, "Economic Histories of Netherlandish Art," Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 15, no. 2 (Summer 2023).

"Dutch terminology used in the seventeenth century to describe existing categories of paintings differs from those used by art historians today. Whereas we now tend to think of seventeenth-century Dutch art in terms of areas of specializations such as genre, portraiture, landscape and istoria (history painting), contemporary Dutchmen adopted more specific categories. Some categories were broken down into myriad subcategories. One might choose from an unassuming breakfast still life ontbijtje or a more ostentatious "banquet" still lifes, or banketje pronkstileven.In Dutch still life painting of the 17th century, *banketje* (banquet pieces) and "pronkstilleven" (ostentatious still lifes) represent two related yet distinct subgenres. The "banketje" typically depicts modestly arranged tables with food, drink, and tableware, emphasizing a sense of refinement and balance. These compositions often carry moral undertones, such as the brevity of earthly pleasures or the virtues of moderation. In contrast, "pronkstilleven" focuses on lavish displays of luxury, featuring exotic objects like imported Chinese porcelain, gleaming gold or silver vessels, and rare delicacies, arranged in dramatic compositions. These works reflect the wealth and global trade networks of the Dutch Republic, often serving as status symbols for their patrons. While "banketje" emphasizes a harmonious aesthetic with moral restraint, "pronkstilleven" revels in the visual impact of abundance and material splendor, showcasing the interplay between artistry, economy, and society in the Dutch Golden Age.

The diversity of categories in seventeenth-century Dutch painting was fostered by the fact that instead of painting to the order the few wealthy and powerful, painters were (for the first time in the history of Western art) producing wares to be consumed by individual buyers of different economic and cultural backgrounds, receptive to pictures of all kinds of subject matter and styles.

Prices were generally low since competition was fierce. In order to survive, each painter had to secure himself a particular style to differentiate his work from others already available. Since it took a very long time to become proficient in any category, painters usually specialized in one area only repeating the same motif until it continued to attract buyers.

Many painters depended on secondary sources of income to survive. Vermeer himself was not able to support his ever-growing family with his painting but depended on the generosity of his well-to-do mother-in-law and the sales of paintings of his colleagues he kept on spec in his home.

Anonymous Duch painter

c. 1619–1625

Oil on panel, 67 x 90.7 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amstedam

When compiling inventories, the otherwise meticulous Dutch notaries generally listed paintings in succinct terms, often simply as beeldeken (small images) or stuckjes (small pieces). In some cases the subject and author, if important, were also noted.

A fair number of Dutch painters worked in different categories although specialization was usually the wiser approach for those of lesser talent. Some successful history painters churned out portraits galore, making much money, and even bordeellijke motifs (bordello scenes), the ethical antithesis of traditional history painting. On occasion, a landscape painter accepted a portrait commission between a sunlit glade and a gloomy view of sea dunes if the pay was good.

Vermeer was one of the few painters who was able to produce masterworks in different categories although his total output, reasonably estimated by John Michiel Montias, was only about fifty to sixty works. However, we cannot know if Vermeer's choice of theme or style was born from personal necessities or if they were to some degree influenced by his clients' expectations.

Training and Technique Briefly

Vermeer, like all great painters, assimilated the fundamental notions of his craft and art via a period of apprenticeship in the studio of a recognized master of the local Saint Luke guild (apprenticeship lasted from four to six years). He later adapted what he had learned to his own personal needs. Even though he was not an extremely versatile artist, Vermeer possessed one of the most refined techniques of Western easel painting. He never lapsed into unthinking repetition of successful technical formulas but continuously experimented with different manners to represent natural phenomena and strengthen the pictorial design throughout his brief twenty-year career.

Although it is not known where or with whom Vermeer studied, there are no signs that he completed his apprenticeship in his native Delft. In the past, the accomplished, but elderly Abraham Bloemaert (Utrecht, 1566–1651) (fig. 1) was frequently cited as a possible candidate seeing the connections between the venerable painter and Vermeer's future mother-in-law, Maria Thins. But Bloemaert died three years before Vermeer had become a master and there is no trace that Vermeer had ever traveled to Utrecht. The senior Delft painter and Catholic friend of Vermeer's family, Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674) (fig. 2), has also been linked to Vermeer's apprenticeship but there is absolutely no trace of Bramer's idiosyncratic Italianate manner in Vermeer's early work. Too, the traditional candidacy of Carel Fabritius (1622–1654), Rembrandt's most promising but short-lived pupil, has been debunked since Fabritius had joined the Delft Guild of St Luke only fourteen months before Vermeer.

Abraham Bloemaert

c. 1625–1630

Oil on canvas, 92 x 117.7 cm.

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis

Leonaert Bramer

c. 1626

Oil on slate, 22 x 33 cm.

The Kremer Collection

However, as the art historian Walter Liedtke noted, the identity of Vermeer's master is a somewhat irrelevant question, since even "if a newly discovered document revealed that in his mid- or late teens Vermeer studied with any particular painter, it would not clarify very much" and that Vermeer's talents "were nurtured by beginning not as a painter's apprentice but as an art dealer's son.Walter Liedtke, Vermeer: The Complete Works (London: Abrams, 2008), 20. In any case, it would seem that the skills displayed in Vermeer's first works were those expected of any well-trained history painter.

It is clear that the young, ambitious Vermeer had attempted to carve out a place within the Holland's elite cultural/artistic milieu. Early in his career, in an age when artistic knowledge was not yet dependent on public museums or glossy art magazines (there were none of either), the resourceful painter evidently was able to gain access to private collections where the most innovative works of art could be studied and discussed. He had most likely introduced himself through the channels that existed between fellow painters and patrons although his mother-in-law Maria Thins (c. 1593–1680) had inviting connections with the Delft patricians and distant family relations with Bloemaert. Furthermore, Maria possessed a discreet art collection and repeatedly demonstrated that she was willing to support the painter in his artistic endeavor. Some of Thins' pictures appear in Vermeer's paintings (see Dirck van Baburen's Procuress in the background of the Lady Seated at a Virginal). Certainly Vermeer's father, who bought and sold paintings as part of his livelihood, must have had more connections than those that have been documented.

The most prominent fact that surfaces from an overview of existing knowledge of Vermeer's technique is that the Delft master worked securely within the technical boundaries of his contemporaries. For all practical purposes his materials were identical to those of his colleagues. This should not come as a surprise. The materials available to artists in the seventeenth century were severely limited when compared to those that can be found in any discreetly furnished art supplies store today. Perhaps, the only noteworthy divergence was Vermeer's lavish use of the costly natural ultramarine blue instead of common azurite. His celebrated lemon-yellow is nothing more than lead-tin yellow found even on the palette of the most modest Dutch painter. In any case, it is likely that whatever their shortcomings, the paints that are now largely available today would have most likely been the envy of any seventeenth-century painter. A typical Dutch palette probably had no more than ten paints upon it at any given time (fig. 3).

Frans van Mieris the Elder

1661

Oil on copper, 12.7 x 8.9 cm.

Getty Collection, Los Angeles

By the seventeenth century, Northern painting studio practices had become fairly standardized. They were for the great part based on procedures pioneered in the Renaissance with the introduction and perfection of the oil painting technique.

More on Vermeer's Painting Technique

While we have a passable understanding of the materials of old artists, including Vermeer's, we know far less about how painters transformed them into images. Nonetheless, as far as we know, Vermeer worked firmly within the boundaries of conventional painting practices and used no unusual pigment or combination of pigments. He methodically employed a camera obscura as an aid to painting but from a broader perspective, his style is more aligned with the school of Dutch fine painting to which he is sometimes associated. And he was somewhat of a latecomer. His celebrated lemon-yellow is nothing more than lead-tin yellow found even on the palette of the most modest Dutch painter. Like most Dutch painters Vermeer seems to have used glazing (over emphasized by modern art historians) with parsimony and according to conventional recipes: there are no examples in Vermeer's canvases of the jewel-liked depth of Van Eyck's blood reds or mineral radiance of his greens.

Cross sections of the paint layers taken from Vermeer's canvases rarely reveal more than three pigments mixed together: pigments were often used straight by themselves or mixed with white or one other pigment, black, white or brown. We find limited evidence of complex intermingling of pigments, but distinct islands of a few pigments according to the specific passage depicted. The only technical anomaly in Vermeer's palette is the abundant use of high quality natural ultramarine instead of the more inexpensive azurite.

Aside from a few passages of extraordinary technical facture, no scholar, painter or conservator has ever felt called upon to use arcane technical practices or secret formulae to explain the astounding visual effects seen in Vermeer's canvases. Moreover, his paint "behaves" like one would expect and never once presents the baffling rheological propertiesRheology is the study of the flow of matter, primarily in the liquid state, but also as "soft solids" or solids under conditions in which they respond with plastic flow rather than deforming elastically in response to an applied force. of Rembrandt's paint that abruptly rips and flows in manners unseen in the art of oil painting.

Both the consistency and flow of Vermeer's paint can be reasonably replicated with common oil paint, basic essential oils and sufficient manipulative skill. The impalpable softness of the fur trim of the sitter's jacket in the Lady Writing, which must be seen to be fully appreciated, is neither a product of some particular material nor out-of-the-ordinary manipulative skill. It is the consequence of the artist's pictorial intelligence. He understood that it is not by inventorying each and every hair that the softness of fur is most powerfully conveyed but by blurring the contours of the trim and reducing chiaroscural contrasts to an absolute minimum.

One might say that most of Vermeer's paintings can be reasonably copied although time, which renders some paints more transparent and alters others, has certainly give certain passages a mystery that was probably lacking in the original The more complex works of Rembrandt, Leonardo, Van Eyck or Titian's simply cannot be copied.

Modern and Traditional Working Methods

One of the most pronounced differences between traditional and modern painting methods is that artists of Vermeer's time seldom practiced what may be today called "direct painting" or then, alla prima (i.e., all at once), where the final color, form and lighting of the work are loosely registered from the very first touches (fig. 4). The direct method, although practiced with success by some Dutch painters to speed the painting process, was deprecated by de Lairesse,After de Lairesse went blind in 1690, he gave lectures on the "infallible" rules of Art which were later collected in two influential books, one on drawing (Grondlegginge der Teekenkunst, 1701) and one on painting (Het Groot Schilderboek, 1707). He wrote that a painter should not only trust his observations and experience following his inspiration blindly. His instinct must be checked by respectful study of the tradition of the ancient and modern masters. hence his expressions "smudging" and "rummaging." According to de Lairesse, it took "someone with a steady hand and a quick brush to complete his concept at one go…" but still, he described them as "clever characters who sought to get some recognition by novelties." Vermeer's paint never obscures the objects it represents as in Rembrandt. The image is always clear.

Instead, "serious" painters were trained to employ a tried-and-proven multi-step method. Then, it took time for an oil painting to levitate. Paint was applied in layers which varied in consistency, density and transparency. The final optical result depended on the combined effect of these layers.

Jan van Goyen

1664

Oil on panel, 068 x 648 cm.

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

In the case of the Great Masters, we should always remember that we are dealing with a preconceived, clearly thought-out pictorial project, where every phase of the painting is executed according to a schedule. The rationale behind this system was that, unlike today, the problems of composition, form and color were addressed separately. Far from stifling artistic inspiration, this methodical step-by-step system allowed the most talented painters to "program" masterworks of exceptional artistic level in considerable numbers and vast dimensions while less-talented artists fashioned dignified, well-crafted paintings. As painter art historian and Rembrandt expert Ernst van de Wetering pointed out, the work of art of a Great Master may be likened to a game of chess, in which many moves have to be considered in advance and which a remarkable combination of calculation and creativity is required if the final outcome is to be a success.Van der Wetering, Ernst. Rembrandt: The Painter at Work (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 222.

Nonetheless, the so-called "loose" painting technique, which de Lairesse deprecated, was lauded by Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687) who found it adapted for suggesting one of the primary goals of Dutch painters of the period: naturalness. Huygens linked naturalness, to a fleet, lively technique. While the traditional "neat" painting technique was suited only for the depiction of immobile architecture, in Huygens' words, it was "certainly not for the depiction of 'free moving things, such as grass, leaves and bushes, or the rendering of the charm that can emanate from ruins in all their shapeless splendour. '"Eric Sluijter, "On Brabant Rubbish, Economic Competition, Artistic Rivalry, and the Growth of the Market for Paintings in the First Decades of the Seventeenth Century," JHNA I:2 (2009)

Vermeer: A Latecomer and Conservative?

While Rembrandt was responsible for shaping much of the painting of his age, Vermeer was not. All summed up, Vermeer was a professional latecomer of sorts. It would seem that he embraced the basic theoretical tenets of European art and fully adhered to common technical procedures of his school even though he worked outside the conventional history painting idiom which had been abandoned by most Dutch painters. Certainly, his works reveal no revolutionary or provocative content.

Dirck Hals

1633

Oil on panel, 33.8 x 28.6 cm.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

Dirk Hals (1591–1656), the brother of the famous portraitist Frans Hals (c. 1582–1666), had already pioneered the letter-writing theme (fig. 5) by 1633, one year after Vermeer was born (Vermeer exploited the letter-writing and letter-reading themes six times during his career). By the time Gerrit ter Borch (1617–1681) had virtually perfected the subject, Vermeer had only just turned from his first faltering history works to this new idiom. Ter Borch's Woman Writing a Letter (fig. 6) predates in composition, theme and mood Vermeer's own work by a similar title, A Lady Writing (fig. 7), by almost a decade.

39 x 29.5 cm.

c. 1655

Royal Cabinet of Paintings, Mauritshuis

The Hague

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1667

Oil on canvas, 45 x 39.9 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C

A comparison between De Hooch's Goldweigher (fig. 8) and Vermeer's Woman Holding a Balance (fig. 9) provides an astounding example to what extent Vermeer was willing to appropriate thematic and compositional elements, practically verbatim, from his colleagues. Such appropriation was hardly unusual for painters of the time. There existed a common reservoir of subjects and techniques that were free to be exploited by any artist.

Pieter de Hooch

c. 1664

Oil on canvas, 61 x 53 cm.

Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas

42.5 x 38 cm. (16 3/4 x 15 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Vermeer identified himself with his native culture. His canvases, in effect, constitute a visual confirmation of the broader moral and social values held by his fellow Dutchmen. His political allegiance is amply demonstrated by the maps of the Dutch Republic which are represented in the background of some of his works, in particular, by the exquisite treatment reserved for the map of the Netherlands which proudly hangs as the backdrop in The Art of Painting. In the early Officer and Laughing Girl, the carefully devised juxtaposition between the figures and the map expresses not only an unmistakable pride in the homeland but also the communion between the people who live there and enjoy the fruits of peace.Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Vermeer and the Art of Painting (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 58. Moreover, Vermeer portrayed the highest cultural and scientific and cultural achievements of his countrymen (The Geographer and The Art of Painting) without a trace of irony.

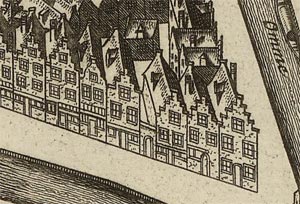

In particular, there exists evidence that Vermeer strongly identified with his native Delft. Anyone who has had the chance to directly view the View of DelftWhile the View of Delft was an image of civic pride, The Little Street was an image of the home and the virtue of its inhabitants. The Dutch ideal of the home was embodied in a contemporary emblem by Roemer Visscher of a turtle captioned "T 'hays best," home is best. or The Little Street (fig. 10) cannot deny the empathetic treatment of these subjects. In Vermeer's time, Delft was conservative, patriotic and provincial. It was considered the cleanest of all Dutch cities,and the Dutch were considered the cleanest of all European populations.Cleanliness is one of the most important necessities for beer brewing and cheese making. In earlier times there had been more than one hundred beer breweries in Delft, so the town's cleanliness (together with the purity of the water) was absolutely essential for beer brewing as one of the principal productions. No doubt, Vermeer was the cleanest painter in Delft. While almost every other painter had left Delft by the late 1660s for the prosperous Amsterdam, Vermeer remained loyally bound to his birthplace until the day of his premature death.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1657–1661

Oil on canvas, 54.3 x 44 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

While from a thematic and technical point of view Vermeer's art might be considered fundamentally conservative, his genius is not subject to dispute. His name now stands above the most highly regarded Dutch genre painters and, indeed, it towers over artists such as Gerrit Dou and Frans van Mieris who were considered as giants by their contemporaries, able to rival even the great Italian Renaissance masters.

Vermeer Amongst the Giants of his Time

Although there is evidence that in the last half of the twentieth century Vermeer's star has risen above that of Rembrandt, Vermeer, contrary to Rembrandt, had only the slightest impact on his contemporaries.

Surviving Dutch paintings that show signs of Vermeer's manner are fewer than twenty and most of these were produced by moderately talented painters now only known to well-informed Dutch art historians (e.g. Jacobus Vrel (fl. 1654–c.1670) and Cornelis de Man (1621–1706). Michael van Musscher (1645–1705)—an enterprising fellow who was able to recycle just about any motif he set his eyes on—did a relaxed remake of Vermeer's solemn Art of Painting (fig. 11 & 12) hardly an event which drives forward the course of art. Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667), equally eclectic but more poetically gifted than Van Musscher, paid homage to Vermeer by scattering a few of the latter's trademark pointillés upon a pair of slippers of an elegant seamstress's skirt in his Woman Reading a Letter with her Maid. In a few other works, a compositional rigor unusual for Metsu but fundamental in the work of his Delft colleague is detectable although problems of dating do not clear up who was influencing whom.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1668

Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Michiel van Musscher

1690

Oil on canvas

Whereabouts unknown (lost in WWII)

Without fear of rebuttal, it is fair to say that Vermeer's influence did not extend far beyond the picturesque city bastions of his hometown Delft. On the other hand, Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo and the great Rubens can be charged not only with altering the course of European artistic production, but to some degree, the course of history as well. In fact, everything in Vermeer's life and art is scaled down in respects to these European giants: the dimensions of his pictures, his total output, his thematic range, the hierarchy of his subject matter as well as the social status of his clientele. Even his personal ambitions, although sincere, were anything but spectacular. While there is documentary evidence to show Diego Velázquez (1599–1660) aspired to become a knight of Santiago, one of the prestigious Spanish military orders reserved for noblemen, Vermeer seems to have been content to become a Schutter in the militia of his tiny Delft which counted amongst them "the most suitable, most peaceful and best qualified burgers or children of burgers." To have escaped his father's inn and installed himself in the Papenhoek (Papist corner) shielded by his mother-in-law's patrician standing may have already been a significant rise in social status for the painter born to the family of a tradesman.

Within a few decades after the Vermeer's premature death, his accomplishments rapidly fell into the shadows. Although a few flagship works held their own among discreet connoisseurs of Dutch painting, some of his works were attributed to other Dutch painters (Pieter de Hooch and Gabriel Metsu) in order to increase their value at public auctions. Vermeer's apotheosis began two hundred years after his death in the mid-1860s when French art critic and left-wing politician Thoré-Bürger published a series of articles eulogizing his little-known works then scattered over the European continent. Enthusiasm soon seized the art world.