Han van Meegeren (1889–1947), born in the Dutch town of Deventer, was the most notorious forger of the twentieth century. He was fascinated by drawing as a child. Despite his father's disapproval, he sometimes spent all his pocket money on art supplies. In high school, he was finally able to receive professional instruction, but went on to study architecture, according to his father's wishes.Denis Dutton, "Han van Meegeren," accessed October 9, 2023. In 1907, compelled by his father's demands, he left home to study at the Technische Hogeschool (Delft Technical College), in Delft, the hometown of Vermeer. There, he received drawing and painting lessons as well. In 1913, he gave up his architecture studies and concentrated on drawing and painting at the art school in The Hague.

Van Meegeren's artistic career began well. He showed his first works publicly in The Hague from April to May, 1917, at the Kunstzaal Pictura. In December, 1919, he was accepted as a member to the Haagse Kunstkring, an exclusive society of writers and painters who met weekly on the premises of the Ridderzaal. In his studio, opposite the Royal Palace Huis ten Bosch, Van Meegeren would paint the tame Roe Deer belonging to Princess Juliana. He made many sketches and drawings of the deer and in 1921, painted Het Hertje (The fawn), which became quite popular in the Netherlands. He undertook numerous journeys to Belgium, France, Italy and England, and acquired a name for himself as a talented portraitist.Wikipedia contributors, "Han van Meegeren," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, accessed October 9, 2023, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Han_van_Meegeren. It is said Van Meegeren's father once told him, "You are a cheat and always will be."

However, after an initial success in the Dutch art circles, critics began to criticize Van Meegeren's work as tired and derivative. The artist felt he had been attacked him unjustly and the hostile critics meant to destroy his career. He decided to prove his talent by forging paintings of some of the world's most famous artists, and by later selling his fakes to Nazi leaders, he had vindicated his culture and country which they had invaded. Or so goes the popular myth.

The real story, rewritten by Jonathan Lopez in The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren, is that Van Meegeren was neither unappreciated artist nor antifascist as he claimed to be, but an ingenious crook who worked virtually his entire adult life making and selling fake Old Masters through networks of illicit commerce that operated across Europe between the wars. Through various front men he had managed to sell fakes to powerful dealers and famous collectors such as Andrew W. Mellon (American businessman and banker as a politician and statesman), Daniël George van Beuningen (Dutch shipping baron and icon for the city of Rotterdam), and Willem van der Vorm (wealthy ship owner and Van Beuningen's arch rival in art collecting). Only a handful of art historians and connoisseurs of the time were able to see through Van Meegeren's scams; the overwhelming number regarded Van Meegeren's forgeries not only as genuine, but often exquisite.

To pass off his fakes, Van Meegeren spent six years researching techniques in complete secrecy, finally producing near-perfect forgeries of paintings attributed to Dutch painters such as Frans Hals, Pieter de Hooch, Gerrit ter Borch and Vermeer. He first made two trial paintings "Vermeers": Woman Reading Music, after Vermeer's Woman in Blue Reading a Letter and Lady and Gentleman at the Spinet, after Vermeer's Woman with a Lute near a Window. Van Meegeren sold neither of these paintings; both are now at the Rijksmuseum. Van Meegeren took the utmost care to employ only the materials and techniques that would have been used by seventeenth-century Dutch artists, which could not be detected by the most of the authentication methods of the time although there were many cases of negligence and nonchalance.

During World War II, a number of wealthy Dutchmen wanted to prevent the sales of precious Dutch Master paintings to Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, and avidly bought Van Meegeren's forgeries. Nevertheless, one of the nation's prized "Vermeers" ended up in the possession of Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring.

Following the war, the forgery was found in Göring's art collection, and after police investigations Van Meegeren was soon arrested as a German Collaborator. Since Van Meegeren's crime brought the death penalty, he had little choice but to confess to his crime and clear himself of the charge of collaboration. Van Meegeren's confession became worldwide news and he was hailed as a hero as "the man who swindled Göring." Meanwhile the art world was thrown into disarray. Many continued to believe Van Meegeren's claim until he painted another "Vermeer" under the court's supervision. The commission examined the eight Vermeer and Frans Hals paintings which Van Meegeren had identified as forgeries. With the help of the commission, the chemist and seventeenth-century painting expert Paul Coremans was able to determine the chemical composition of van Meegeren's paints. He found that van Meegeren had prepared the paints by mixing them with the plastic bonding agent Albertol, a phenolformaldehyde resin which had been invented only in the twentieth century. A bottle with exactly that ingredient had been found in Van Meegeren's studio.

On November 12, 1947, Van Meegeren was convicted of falsification and fraud, and sentenced to the minimum punishment of one year in prison. He never served his sentence, but before he could be incarcerated the forger suffered a heart attack and died on 30 December, 1947.

Van Meegeren never admitted to creating any fakes dating from before 1937, but there have always been rumours suggesting that his career had, in fact, begun much earlier than that. It is estimated that Van Meegeren duped buyers out of an estimated 25 to 30 million dollars. Until he had been arrested, Van Meegeren had lived in great luxury.

Photograph

Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam

How could have Van Meegeren's forgeries fooled even the great art historians of the time? "In essence, what these forgeries had done was to re-interpret Vermeer in the light of art inspired by Nazi ideology—with which Van Meegeren ...sympathized. The late Vermeer forgeries are basically a Nazi fantasy of Vermeer, and this was, of course, an entirely plausible image of Vermeer if you happened to be living in occupied Europe during the war, when Nazi imagery was an absolutely ubiquitous part of daily life."Jonathan Lopez, The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008).

The Van Meegeren trial denoted a serious shortcoming in connoisseurship. A large number of experts had failed to recognize the forgery as such, thus they were apparently unable to distinguish between an authentic old master and a fake. This painful conclusion not only affected the reputation of connoisseurs in the field of Dutch seventeenth-century art—more so than any previous error had done—but also heightened the awareness of the difficulty of attributing and dating paintings. As a result, some scholars became more cautious when authenticating and dating paintings while others tried to avoid connoisseurship altogether. Both developments were fuelled by new impulses in the next decades.

The need for a more precise, cautious approach when attributing and dating paintings was particularly evident in Vermeer research.

The Van Meegeren case had a deep impact not only on his contemporaries—some art dealers were financially ruined and many hitherto untouchable art historians academically discredited—but on future generations as well. Vermeer's oeuvre was drastically revised, as was the role of the connoisseur and art historian. Apart from the practical problems of attribution that preoccupy curators and art historians, a theoretical question became a subject of heated discussions since the late 1960s: Is there, after all, any aesthetic difference between a deceptive forgery and an original work of art?

The Supper at Emmaus

Han van Meegeren astutely painted The Supper at Emmaus as an early Vermeer to fill in a gap in Vermeer's surviving production. Since some scholars had come to believe that Vermeer had visited Italy in his formative years, the cunning forger validated their theory by providing a "missing link" between the painter's initial history works and the subsequent interiors.

Han van Meegeren

1936–1937

Old canvas, relined, 115 x 127 cm.

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

The composition of Van Meegeren's Supper at Emmaus is strongly reminiscent of a work by Caravaggio. However, the blue-yellow color harmonies, the broken bread and the white ceramic jug are characteristic of Vermeer's mature works. Moreover, the composition seemed to bridge the gap between Vermeer's earlier history paintings and his later interiors.

Van Meegeren gave the work to his unsuspecting friend, the attorney C. A. Boon, telling him it was a genuine Vermeer, and asked him to show it to Abraham Bredius, one of the world's most important Dutch art scholars of the time, who was living nearby in Monaco. Bredius examined the forgery in September 1937, and despite some initial doubts, he accepted it as a genuine Vermeer. Bredius published an enthusiastic appraisal of the picture in the Burlington Magazine ("every inch [is] a Vermeer"). The art historian's opinion was so highly valued that other leading art-historians, including Abraham M. Hammacher, Thomas H. Luns, Johan Q. van Regteren Altena, Frithjof W. van Thienen and Ary Bob de Vries, soon fell in line and accepted his judgment. Largely based on Bredius' recommendation, Dirk Hannema, the director of the Museum Boijmans, acquired the work. It remained proudly displayed there until its true identity was discovered after World War II.

Vol. 71, No. 416, page 211 (Nov., 1937) with an article by Abraham Bredius announcing the finding of The Supper at Emmaus.

Despite some doubts, The Supper at Emmaus was purchased by The Rembrandt Society for 520,000 guilders, with the aid of Van der Vorm and donated to the Museum Boijmans in Rotterdam. In 1938, it was highlighted in a special exhibition at the same museum along with 450 Dutch masterpieces dating from 1400–1800.

In the Magazine for the History of Art, Adolf Feulner wrote in reference to the exhibition, "In the rather isolated area, in which the Vermeer picture hung, it was as quiet as in a chapel. The feeling of the consecration overflows on the visitors, although the picture has no ties to ritual or church." The emotional experience of the picture was so profound that many art critics no longer questioned the authenticity of the piece.

With Emmaus as the benchmark, Van Meegeren no longer had to compete with Vermeer. Now he could churn out forgeries that only had to measure up to his own forgiving standard. Even better, each new fake broadened the definition of what counted as a Vermeer, so Van Meegeren's task grew easier and easier as "is "Vermeers" grew worse and worse.Edward Dolnick, The Forger's Spell: A True Story of Vermeer, Nazis, and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieth Century (New York: Harper Perennial, 2008), 214.

With the money earned from the sale of The Supper at Emmaus, Van Meegeren moved to Nice where he bought a 12-bedroom estate at Les Arènes de Cimiez. On the walls of the estate hung several genuine Old Masters. There he made the Interior with Cardplayers and Interior with Drinkers, painted in the style of Pieter de Hooch.

Recent analysis of the painting shows that Van Meegeren's paint also contained pigments that were not introduced until the nineteenth century. It has also emerged that there were indeed concerns about the authenticity of the 'Vermeers' at the time. The diary of Willy Auping (then curator at the Kröller-Müller Museum) has recently come to light. In it he writes disparagingly of The Washing of the Feet by 'Vermeer', purchased by the Rijksmuseum at the time for the extraordinarily high sum of 1.3 million guilde"s: "Everything is just bad and crude and I really don't know what I can say about it, but it is absurd to believe for one moment that the great Johannes Vermeer of Delft could ever have made such a bad painting as this […]."Friso Lammertse et al., Van Meegeren's Vermeers - The Connoisseurs Eye And The Forger's Art (Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, 2011).

Lady and Gentleman at the Spinet

Han van Meegeren

Oil on canvas

c. 1932

Instituut Collectie Nederland, Amsterdam

Today, The Lady and Gentleman at the Spinet by Van Meegeren seems to be little more than a weak collection of Dutch genre painters and Vermeer props and compositional devices. The standing man strikes a similar pose as that of the man in Vermeer's Music Lesson whereas the seated woman seems to have been drawn from other female genre figures of Gabriel Metsu, Pieter de Hooch or Nicolas Maes. The repoussoir tapestry and ebony-framed landscape in the background are snitched from other compositions by Vermeer. The spinet is the same of those of the Vermeer's Lady Standing and Lady Seated at a Virginal.

As soon as the work was introduced into the market by J. Tersteeg, a writer and publisher familiar with Van Meegeren, it drew unfavorable comments. Tersteeg sold the picture to the Goupil Gallery, Paris, who then sold it to the German Banker, Fritz Mannheimer. It had been turned down by other galleries even though it carried a certificate of authenticity of Abraham Bredius, who had previously heavily criticized Hofstede de Groot and Wilhem von Bode for having on numerous occasions issued certificates of authenticity. When Van Meegeren painted the Gentleman and Lady, he had learned to target individual tastes of authoritative art historian.Jonathan Lopez, The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008), 111. It contained several elements of Vermeer's late Allegory of Faith, which Bredius had himself discovered.

Abraham Bredius, one of the world's most important Dutch art scholars of the time solemnly announced the Gentleman and Lady as a "masterpiece of the Great Man of Delft." Bredius was also the director of Mauritshuis museum in The Hague, connoisseur and art collector. Raised in a wealthy family, his father was Johannes Jacobus Bredius the director of a powder factory in Amsterdam. His family collected Chinese porcelain and seventeenth-century Dutch paintings, which Bredius would build upon.

According to the Van Meegeren expert Jonathan Lopez, the picture's technical faults are largely due to the forger's use of new material to mix paints, Bakelite, which would, however, resist the alcohol test that was used to unmasked forged paintings whose paint had not been allowed enough time to thoroughly harden. However, paints mixed with Bakelite were much harder to handle than traditional oil paints, which instead can be softly fuse since they dry slowly and allow the painter to as much time as he needs to model forms and obtain nuances of light and shade. Tangled up with the struggle to master the unmanageable medium, Van Meegeren fell back on his precisionist skills he had learned in his studies of architecture, making the painting looked "weirdly precisionist."Jonathan Lopez, The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008).

Click here to access a high-resolution image of this painting.

Woman Playing the Lute

Han van Meegeren

c. 1933

58 x 47 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Once Van Meegeren had set up his studio in Nice, France, he continued to perfect his technique with the new Bakelite medium.

The figure of the young lady, who wistfully gazes out the window while tuning her lute, is obviously drawn from Vermeer's Woman with a Lute while mirror with the girl's reflection as well as the legs of the artist's easel, was drawn the Music Lesson. Van Meegeren made a rather clumsy attempts to imitate Vermeer's trademark pointillés caused by the camera obscura. The contours are brittle and inexpressive while the reflection in the mirrors is sharper, instead of hazier than the foreground objects.

The painting was never sold.

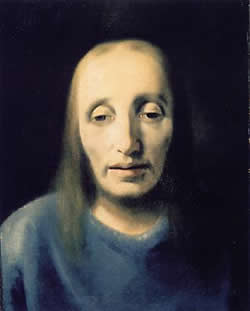

Click here to access a high-resolution image of this painting.Head of Christ

Han van Meegeren

c. 1939

Oil on old canvas, relined, 48 x 30 cm.

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Van Meegeren presumably painted this head of Christ in Nice by about 1939, before he returned to Holland.

The painting was introduced to the market by Rens Strijbs, a respectable figure and acquaintance of the Van Meegeren. It is likely that he did not know the painting was a forgery because he had been told by Van Meegeren that it came for an "old family" and Strijbs was anything but an art expert.

When he presented himself at the Hoogendijk gallery in Amsterdam, the dealer had no doubt it was an original Vermeer even though he did not know who Strijbs was. Dirk Hannema and Jonkheer David Roell, who were both directors at the Rijksmuseum, believed it was as study for Supper at Emmaus. In February 1941, Strijbs demanded 500,000 guilders in cash but received 475,000.Jonathan Lopez, The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008), 166–167. The paintings was bought by Van Beuningen but later sold to help finance the acquisition of the much costlier Supper at Emmaus.

Strijbs sold a total of four forgeries by Van Meegeren.

The Last Supper

Han van Meegeren

174 x 244 cm.

Whereabouts unknown

This was sold in 1941 to Van Beuningen, again via Strijbs and Hoogendijk, for 1,600,000 guilders. Van Beuningen paid for the work with "lesser" paintings from his collection, including, ironically, the Head of Christ. Van Meegeren had painted both this picture and the Head of Christ before leaving Nice.

Although the Utrecht-born Van Beuningen had made his fortune in shipping, he styled himself as an art connoisseur and collector. His economic success enabled him to become well known in the Netherlands and many other countries. He built a prestigious art collection including works by Southern and Northern Dutch primitives, seventeenth-century Italians, El Greco, 18th- and 19th-century French painters, Neo-Impressionists and Van Gogh. He donated a long series of gifts and loans to Rotterdam Museum Boijmans, which afterward was renamed Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in his honor.

Having reached an advanced age, Van Beuningen

continued to defend the authenticity of some of Van Meegeren's Vermeer fakes. In the 1940s, he financed Dirk Hannema and Jean de Coen, an eccentric Belgian art historian in their efforts to defend some of Van Meegeren's Biblical fakes. De Coen was convinced that The Supper at Emmaus and The Last Supper were genuine but held The Woman taken in Adultery, The Blessing of Jacob and The Footwashing to be crude imitations of a second-rate artist suffering folie du grandeur.Frank Wynn, I Was Vermeer: The Rise and Fall of the Twentieth-Century's Greatest Forger (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2006), 208. In 1950, De Coen published a lavishly illustrated book entitled Retorur a la Vérité, in defense of two works.

Van Beuningen demanded that Paul B. Coremans, who had published a book with evidence proving that the paintings in question were fakes by Van Meegeren and not Vermeer, publicly admit that he had erred in his analysis. When Coremans refused, Van Beuningen sued him, alleging that Coremans' wrongful branding of The Last Supper II diminished the value of his "Vermeer" and asked for £500,000 in compensation. The trial was set for 2 June, 1955, but was delayed owing to Van Beuningen's death on 29 May, 1955. Approximately seven months later, the court heard the case on behalf of Van Beuningen's heirs and ruled in favor of Coremans. Wikipedia contributors, "Han van Meegeren," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, accessed October 9, 2023, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Han_van_Meegeren.

Van Beuningen's heirs agreed to make the magnate's fake Vermeer's available to the museum which was named as a token of gratitude to Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen.

The Blessing of Jacob

Han van Meegeren

c. 1942

Oil on canvas (?), 125 x 115 cm.

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

The Isaac Blessing Jacob was the first fake Vermeer with a religious subject that Van Meegeren had painted in the Netherlands. It is far lower in standards than the other fakes he had previously done. When later questioned why he had not tried harder on his fifth Vermeer, he candidly responded that "they sold just the same."

Nonetheless, in 1942 the Hoogendijk gallery, via Rens Strijbs, sold it easily to the wealthy industrialist and arch rival of Van Beuningen in art collecting, W. van der Worm, for 1,270,000 guilders. The Isaac Blessing Jacob was the last Van Meegeren fake that Strijbs, who would later deny at Van Meegeren's trial that he knew the paintings he had trafficked were forgeries.

Woman Taken In Adultery

Han van Meegeren

c. 1943

Oil on canvas (?), 96 x 88 cm.

Instituut Collectie Nederland, Asmterdam

In 1942, this picture had passed from Van Meegeren through the hands of a number of intermediaries. It was disputed by Heinrich Hoffman, Hitler's personal art advisor and Hermann Göring, who ardently desired a Vermeer for his private art collection. On the contrary, Hoffman argued that such an important work by Vermeer should go only to the Führer himself, for his art collection to be housed in Linz, Austria.

It was sold to a Nazi banker and art dealer Alois Miedl who later sold it to Göring for 1,650,000 guilders, the highest price ever paid for one of Van Meegeren's forgeries.

Göring attempted to reclaim the painting at the end of the war once it had been recovered from Nazi art hoard buried in the Alt-Aussee salt mine in Austria. Göring showcased the Vermeer forgery at his residence in Carinhall, near Berlin. In August 1943, Göring hid his collection of looted artwork, including his "Vermeer," in an Austrian salt mine, along with 6,750 other pieces of artwork looted by the Nazis. On 17 May, 1945, Allied forces entered the salt mine and recovered all the artworks.

Göring "Vermeer" was soon traced back to Van Meegeren and was ultimately responsible for bringing his career of forgery into the open.

It is said that when Göring had learned that Van Meegeren had forged his treasured "Vermeer," he looked as if for the first time he had discovered there was evil in the world."Frank Wynn, I Was Vermeer: The Rise and Fall of the Twentieth-Century's Greatest Forger (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2006), 208.

The Washing of the Feet

Han van Meegeren

c. 1943

Oil on canvas (?), 122 x 102 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam<

In 1941, aside from illicit activity, Van Meegeren continued to make many of his own drawings, some of which he published in the following year in Han van Meegeren: Teekeningen I, a luxurious book. At the same time, he worked on several forgeries in the manner of Vermeer including The Head of Christ, The Last Supper II, The Blessing of Jacob, The Adulteress and The Washing of the Feet.

In 1943, Van Meegeren turned to a new front man to sell his forgeries, this time an old school acquaintance, Jan Kok, who knew nothing about or art, art dealing or Van Meegeren's illicit commerce. Kok brought Van Meegeren's Footwashing to the reputable art gallery of Pieter de Boer, in Amsterdam. De Boer had been known for his dealing with the Germans. When De Boer saw the picture, he contacted Herman Vos, the director of Adolf Hitler's Führermuseum. Vos turned down the picture despite the fact that Vitale Bloch, the Russian Jewish expert and collector who is said to have collaborated closely with the Nazis, had authenticated it as a genuine Vermeer.

After having proposed The Washing of the Feet to the Nazis, De Boer offered it to the Rijksmuseum to "keep the picture for the Netherlands." Rumor had it that Walter Andreas Hofer, the chief curator of Hermann Göring's art collection, was looking for a Vermeer painting. The Rijksmuseum committee was not enthused by the work, and one committee member declared it a forgery. The painting was examined by the chief of conservation of the Mauritshuis, A. M. de Wild, and confirmed authentic. Fearing technical examinations, Van Meegeren had painted the pictures with methods and materials of the seventeenth century anticipating all the tests that would have been used to discover his misdoings. He had employed a seventeenth-century canvas and pigments such as natural ultramarine, cinnabar and white lead.

In July 1943, the Rijksmuseum paid 900,000 guilder backed up by 400,000 guilders donated by the shipping magnate Wilhelm van der Vorm through the Rembrandt Society.

Click here to access a high-resolution image of this painting.

Woman Playing Music

Han van Meegeren

1935–1936?

Old canvas, unsigned, 58.5 x 57 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

This is one of Van Meegeren's "traditional" Vermeers. As can be plainly seen, it was partly cribbed from the authentic Woman in Blue Reading a Letter in the Rijksmuseum and A Lady Writing in the National Gallery of Washington. This picture, like the Woman Playing Music, remained unsold and was later found in Van Meegeren's Nice studio a decade after they were both painted. It has been suggested that they were never sold because Van Meegeren felt that they were too like real Vermeers as far as subject matter was concerned and thus exactly what a forger would be expected to produce.

Details of Vermeer's Woman in Blue Reading a Letter and Van Meegeren's Woman Reading Music can be viewed side by side below. In an attempt to make his pastiche more credible, Van Meegeren added a large drop pearl and a pearl necklace, both props repeatedly represented by Vermeer. Although the modeling of Van Meegeren's head is less subtle than Vermeer's, it should be taken into account that Van Meegeren was forced to mix his pigments with the synthetic medium Bakelite, which dried quickly and did not allow him to fuse and blend his paints, in order to disguise it had been painted freshly.

Click here to access a high-resolution image of the painting.

Thefts, forgeries & the Van Meegeren case

The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren

The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van MeegerenJonathan Lopez

2009

The Forger's Spell: A True Story of Vermeer, Nazis, and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieth Century

The Forger's Spell: A True Story of Vermeer, Nazis, and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieth CenturyEdward Dolnick

2009