Although art theft has always existed, it has dramatically increased in the twentieth century. It is not known exactly how much art is stolen, but estimates now range into billions of dollars each year. Interpol maintains that art-related crime is exceeded only by drug trafficking, money laundering and illegal arms dealing.

In 1911, Vincenzo Peruggia executed what is often regarded as the greatest art theft of the twentieth century, stealing the Mona Lisa (fig. 1) from the Louvre. Contrary to the initial police theory that he hid inside the museum overnight, Peruggia revealed during his interrogation that he entered the museum early on the morning of August 21st, blending in with other workers by wearing a white smock. He waited until the Salon Carré, where the Mona Lisa was displayed, was empty, then removed the painting from its wall mountings and took it to a service staircase. There, he dismantled its protective case and frame. While some reports suggest he hid the painting under his oversized smock, Peruggia, being only 160 cm. tall, countered this by saying he wrapped the painting in his smock and carried it under his arm, exiting the museum through the same door he entered.

On the evening of September 23, 1971, Mario Pierre Roymans, a twenty-one-year-old hotel waiter, executed a daring theft of Vermeer's The Love Letter (fig. 3) from the Fine Arts Palace in Brussels. The painting was part of the "Rembrandt and his Age" exhibition and on loan from the Rijksmuseum. Roymans concealed himself in an electrical box within the exhibition hall, emerging after hours to steal the painting. Struggling to remove the painting from its frame, he resorted to cutting it out with a potato peeler, damaging it in the process. Initially hiding the canvas in his room, Roymans later buried it in a forest, only to retrieve it during rain and conceal it under his mattress in the Soetewey Hotel where he worked.

On 27 April, 1974, along with a Goya, two Gainsboroughs, three Rubens, and twelve more paintings, Vermeers' late Lady Writing with her Maid (fig. 4) was stolen from the Russborough House, near Dublin, the home of Sir Alfred Beit, by armed members of the Irish Republican Army.

On Saturday night February 23, 1974, anonymous thieves smashed through a metal-bar protected window of the Kenwood House with a sledgehammer, snatched Vermeer's priceless Guitar Player (fig. 5) from the wall, scaled a ten foot wall outside the museum grounds and fled undisturbed. On March 18, 1990, The Concert (fig. 6) was stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Musuem in Boston by two thieves disguised as policemen and was never recovered.

Only the minority of art-related crimes are reported and only the minority of stolen art is recovered—estimates range from a desultory five to ten percent. Artworks stolen in a few minutes often take years to recover.

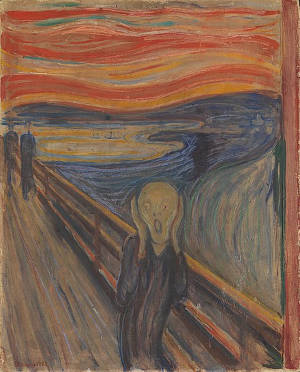

The Scream (fig. 2), Edvard Munch's iconic painting, has been the target of two major thefts. The first occurred in 1994 at the National Gallery in Oslo, where thieves stole a version of the painting during the Winter Olympics, exploiting inadequate security measures. The thieves left a note reading "Thanks for the poor security." This version was later recovered in a sting operation. A decade later, in 2004, another theft at the Munch Museum in Oslo saw a different version of The Scream, along with Munch's Madonna, stolen in daylight by armed thieves. Both artworks were recovered in 2006. These high-profile thefts highlighted significant security lapses in art institutions and led to increased efforts to protect cultural heritage.

Leonardo da Vinci

c. 1503–1506

Oil on poplar panel, 77 x 53 cm.

Louvre, Paris

Edvard Munch

1893

Oil, tempera, pastel and crayon on cardboard, 91 cm × 73.5 cm.

National Gallery and Munch Museum, Oslo

About 98% of art crimes take place in Europe and the United States. A quarter of stolen art is taken from art institutions or museums, half from private individuals. Art works of minor importance find their way into a complex criminal underground and only after years are they "laundered" and can be resold through "legitimate" channels. Important works of art must be ransomed. It is nearly impossible to sell a stolen iconic art work for anywhere near its true value. Because it is so difficult to resell, important works of art are used as a form of currency among criminals. "As thieves see it, art-napping is kidnapping without all the fuss. Here is a victim who won't cry out or jump out the window and who just might bring a giant ransom."Edward Dolnick, "Art thieves are not like Thomas Crown—but they are eternal optimists," The Guardian, October 17, 2012, accessed November 17, 2023. Moreover, if an art thief is caught, he will spend very little time in jail compared to a convicted kidnapper. Once stolen, artwork is recovered either very quickly after the theft or decades later.

Gentlemen aesthetes who steal art as a sophisticated diversion or art-addicted burglars with an unquenchable passion for beauty are largely a Hollywood myth—real-world art thieves often use stolen works of art for collateral in international drug deals. Exceedingly few cases of rich, but unscrupulous art lovers who commission major art thefts have ever been reported. In one unusual case, the compulsive French art thief Stéphane Breitwieser admitted to authorities he had stolen more than two hundred works from small museums across Europe, keeping most of them at his home purely for enjoyment. He was sentenced to twenty-six months but was arrested six years later when the police found twenty-nine works of art in his apartment.

Art thieves rarely destroy their loot. "The vast majority of art thieves use their plunder as collateral instead, using the works as leverage to bargain down criminal charges. Throughout Europe, prosecutors are generally willing to lessen a criminal's sentence if he can offer a valuable piece of stolen art in exchange. (Such deals are rare in the U.S.) In Spain, gangs have even taken to stealing art as insurance, using the purloined pieces to reduce criminal sentences for unrelated charges like drug possession and car theft."Mark Joseph Stern, "How Often Do Art Thieves Destroy Their Loot? Basically Never," Slate, July 19, 2013, accessed November 17, 2023.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1667–1670

Oil on canvas, 44 x 38.5.cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

(stolen 23 September, 1971)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1671

Oil on canvas, 71.1 x 58.4 cm.

National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

(stolen February 23, 1974

and 27 April, 1974)

The principal reason why artworks are targeted by criminal organizations is that they are easy to steal and many can be conserved indefinitely with little or no fuss. A painting worth tens of millions of dollars can be cut out of its frame, rolled up, and carried away in a cardboard tube within minutes.

Because state-of-the-art security of the kind commonly employed by money-making enterprises like banks and jewelers is so expensive, individual collectors and art institutions have great difficulties of protecting their art as well as tracking and recovering it when it does get stolen. While most high-profile museums have extremely tight security, many places with multimillion-dollar art collections have disproportionately poor security measures. Art theft has also had great economic impact on the finances of art institutions. To protect their traveling artworks from theft, insurance may account for up to one-third of the budget for an exhibition.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1673

Oil on canvas, 53 x 46.3 cm.

Iveagh Bequest, London

(stolen February 23, 1974)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1663–1666

Oil on canvas, 72.5 x 64.7 cm.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

(stolen March 18, 1990)

Over the years, Interpol, the FBI and other police agencies have compiled comprehensive lists of stolen works and frequently e-mail art alerts. Online lists like the Art Loss Register or Trace Looted Art make cross-checking easier. The FBI has a dedicated Art Crime Team of 14 special agents, supported by three special trial attorneys for prosecutions. Additionally, it runs the National Stolen Art File, a computerized index of reported stolen art and cultural properties for the use of law enforcement agencies worldwide.

† FOOTNOTES †

Thefts, forgeries & the Van Meegeren case

The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren

The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van MeegerenJonathan Lopez

2009

The Forger's Spell: A True Story of Vermeer, Nazis, and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieth Century

The Forger's Spell: A True Story of Vermeer, Nazis, and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieth CenturyEdward Dolnick

2009