We know that by 1660, Johannes Vermeer and his family had been living together in his mother-in-law's (Maria Thins; c. 1593–1680) house at Oude Langendijk, south of the Markt, the large market square. Official documents from the seventeenth century refer to this area as "Achter het Marktveld" (behind the market square), in the heart of Delft's Catholic community, the Papenhoek (Papists' Corner) adjacent to the Nieuwe Kerk. The first document which unequivocally proves that the Vermeer and his wife Catharina Bolnes(c. 1631–1688) had changed living quarters is dated December 27, 1660 although it is possible he made his move somewhat earlier. We do not know where they lived prior to this move but the house and inn owned by his father, Mechelen on the Markt (Market Place) is the most likely candidate. From a topograpaphical point of view, the move from Mechelen to Oude Langendijk was a short one, perhaps no more than 120 paces across the Markt. But from social point of view, it was worlds apart. The Papenhoek was not a ghetto because many families chose to live there by their own free will, and were prosperous. In Delft about a quarter of the population was Catholic.

"The Catholic faith, nurtured by the Jesuits, was part of the DNA of the Papenhoek, which had a significant influence not only on Vermeer’s family life but also on his art. The repressed religion also contributed to the neighbourhood's solidarity. Its residents practised their faith with great caution, individually as well as collectively. In Vermeer’s time, after all, there was less of a separation between the private and public domain in the city than today. A tightly organized community contributed to a specific social culture: residents had neighbourly duties, there was much social control, and neighbours helped one another."Peter Roelofs, "Closer to Vermeer," in VERMEER, ed. Pieter Roelofs & Gregor Weber, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023, 45.

No one knows why Vermeer made this move. Was it a part of the Vermeer/Thins marriage arrangement by which the painter agreed to convert to the Catholic faith, or was it simply a question of finances? Perhaps one or both parties believed Mechelen was not suited to bring up children. In any case, Vermeer and Catharina moved into Maria Thins' home when he was approximately twenty-eight years old. By then he had painted his masterpiece View of Delft and begun to experiment with the interior subject such as The Milkmaid and the Officer and Laughing Girl. Once he had become accustomed to his new residence, he set out to paint a series of sublime masterpieces which are so perfect, that one critic called them the "pearl paintings."Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, Woman Holding a Balance, Woman with a Pearl Necklace, and the Woman with a Lute.

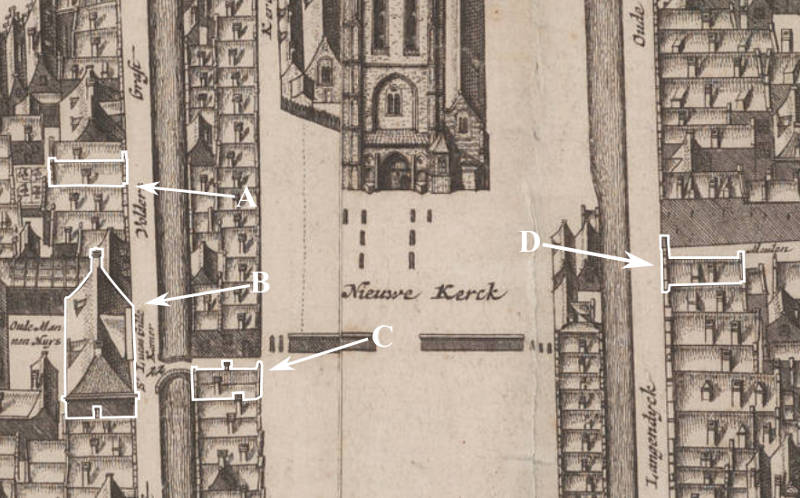

A. Flying Fox (Vermeer's presumed birthplace and inn of his father)

B. The Delft Guild of St. Luke (professional organization of artists and artisans)

C. Mechelen (a large tavern on the Market Square rented by his father where Vermeer and his family lived after the Flying Fox

D. Groot Serpent (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

E. Trapmolen (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

The Exact Location of Vermeer's Dwelling: Competing Hypotheses

The following discussion draws from these sources:

- Slager, H.G.. "Vermeer’s house again and the Jesuit church," October 2024. Accessed October 24, 2024 URL: https://www.essentialvermeer.com/misc/SLAGER-VermeersHouseAgainandtheJesuit%20Church.pdf

- Grijzenhout, Frans, "Finding Vermeer: Back to the Molenpoort," Accessed October 24, 2024 URL: https://www.essentialvermeer.com/misc/finding-vermeer.html

- Roelofs, Peter. "Closer to Vermeer." In Exhibition catalogue Vermeer, edited by Pieter Roelofs and Gregor Weber, 46. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2023, 46-50.

- Slager, H.G. "Vermeer and His Neighbours." Ommen, 2017. Online paper. Essential Vermeer. Accessed December 28, 2023 URL: http://www.essentialvermeer.com/history/neighbours-slager.pdf.

- Slager, H.G. "Vermeer’s House Revisited." Ommen, 2018. Online paper. Essential Vermeer. Accessed December 28, 2023 URL: http://www.essentialvermeer.com/history/vermeers-house-revisited-slager.pdf.

- Wiel, Kees van de, with thanks to Hans Slager and Wim Weve. "Oude Langendijk 25." Achter de gevels van Delft. Accessed December 28, 2023, URL: https://www.achterdegevelsvandelft.nl/huizen/Oude%20Langendijk%2025.html.

Before moving from Gouda to Delft, Maria Thins had a particularly unhappy marriage, filled with anguish and domestic violence. When Maria divorced from her husband, Reynier Bolnes (died c. 1593), a prosperous but irascible brickmaker, she was able to claim a sizable share of money through the legal proceeding which followed, and moved into a house in Delft, which would eventually become the domicile of Vermeer, Catharina, and Maria (?),The estate inventory of Catharina Bolnes, widow of Johannes Vermeer, is divided into two sections. The first records Catharina's personal effects in the house on the Oude Langendijk, including items owned by Vermeer until his death. The second section lists items shared with her mother, Maria Thins, primarily large furniture, paintings, and small household goods, located in Maria's residence on the Oude Langendijk. The inventory's wording suggests it was drawn up by Catharina, indicating Maria was not present or living there in 1676. This challenges the view that Catharina and Johannes lived with Maria Thins. Documents show that Maria Thins and the Vermeer-Bolnes family lived on the Oude Langendijk since the 1660s, sharing a house in 1663. However, Maria likely moved to a smaller house, Fonteijn, after 1667, leaving some larger items with Johannes and Catharina. She sold Fonteijn in 1679 and lived with relatives on the Begijnhof before her death in 1680. The Trapmolen house on the corner of the Molenpoort is identified as the location of the estate inventory and where Maria Thins was carried from to her burial, contradicting previous assumptions about their residence. and perhaps, the location of the artist's studio as well.

Over the past century and a half, earnest researchers such as Henri Havard, an Rijksmuseum director Frederik Obreen, the art historian Abraham Bredius, the archivist A.J.J.M. van Peer,In 1957 Van Peer, a Delft inhabitant who had undertaken extensive research on Delft city history in archives, was the first to the inventory of movable goods in Vermeer's/Catharina Bolnes' Oude Langendijck residence in full in: A. J. J. M. van Peer, "Rondom Jan Vermeer van Delft," Oud Holland 74 (1959): 240-245. the American Vermeer economist/Vermeer biographer John Michael Montias, the archivist Hans Slager and art historian Frans Grijzenhout have attempted to identify which location Vermeer and his family lived in the later part of the artist's life.

One year after Vermeer's death in 1675, at the top of the estate probate inventory,Many objectsof the inventory seem correspond to those represented in the artist's interiors paintings. While it is not possible to affirm beyond a doubt that they are one and the same, it seems quite probable that he did, for Vermeer's studio was in the house in which he lived and the home was very much the center of Dutch life in the seventeenth century. As one seventeenth-century Dutch merchant declared, "My home is my ornament, my house is my best costume, Therefore my treasury and my coffer are open/And what my house needs I hasten to buy." the notary’s clerk described Vermeer, his wife Catharina Bolnes and mother-in-law as "domiciled on the Oude Langendijk," scribbling between the lines the more precise location "on the corner of the Molenpoortsteeg [today's Molenpoort]." Official documents from the seventeenth century refer to this area as "Achter het Marktveld" (behind the market square), but because the majority of its residents were Catholics, it was colloquially known as the Papenhoek (Papists’ Corner), a nickname not entirely devoid of contempt. Scholars have long debated on which corner of the Molenpoort was meant: the east or the west?In whichever house they resided, Maria Thins and her daughter Catharina would remain in this respectively until 1680, when Maria died nd 1684, when Catharina relocated to Breda.

On the west corner once stood a house called Trapmolen, (today’s Oude Langendijk 25) (fig. 1) on the east, a particularly large house once referred to as Serpent, which was eventually demolished in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, replaced by the neo-Gothic Maria van Jessekerk that stretches along the whole east side of the today's Jozefstraat. A commemorative plaque (fig. 2), an initiative of the Dutch art historian and Vermeer/Delft expert Kees Kaldenbach, signals the place for today's curious.On June 20, 2003 the official Dutch Traffic Board ANWB placed at the Delft canal location Oude Langendijk a large panel containing various images of the house which once stood right there. For several decades, art history literature, influenced by Van Peer, consistently asserted that Vermeer’s family lived in Maria Thins’s house,The house was presumably owned by MariaThins, Vermeer's supportive mother-in-law, who owned other properties in Delft, including no fewer than four neighboring houses on the Oude Langendijk, and lived in the Swanenburg house, a larger building with greater status, located four houses west of the Trapmolen. Serpent house.

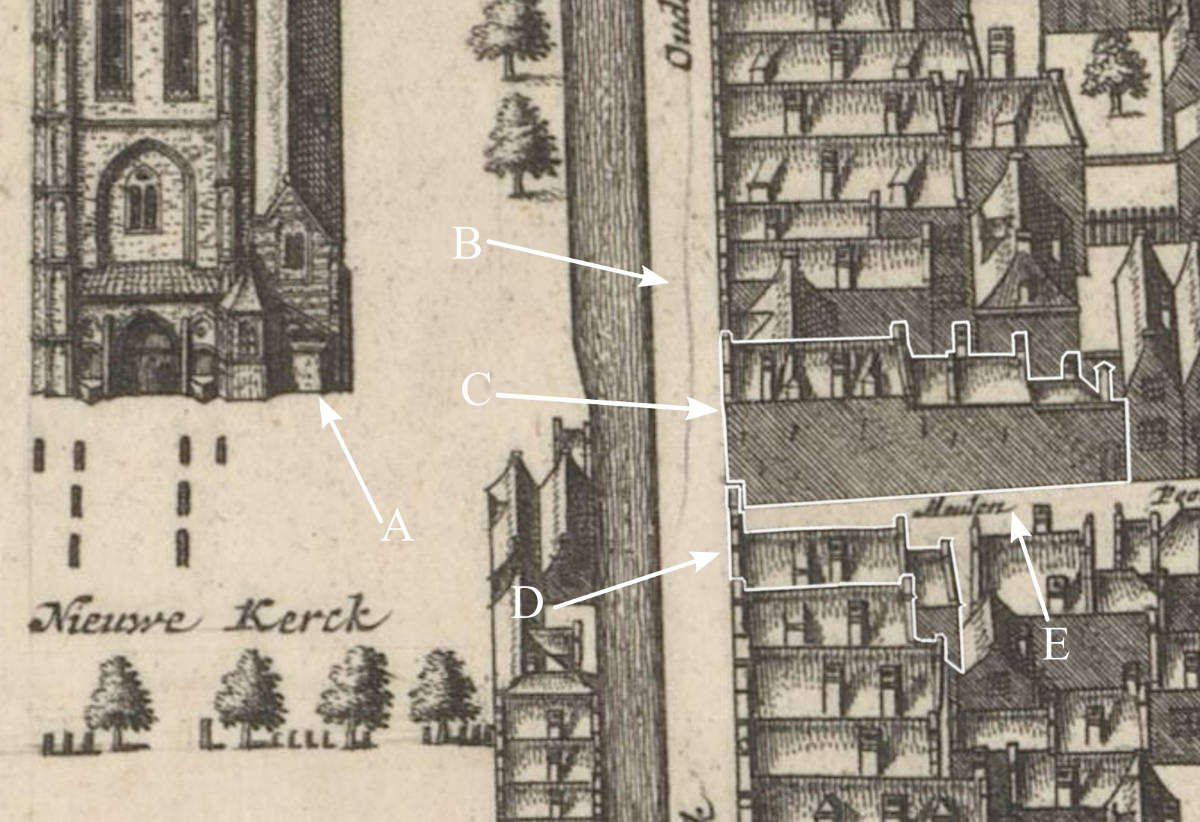

The Kaart Figuratief (fig. 3), an illustrated map representing a bird’s-eye view of the city the city from 1675–1678, allows us to visualize the precises location and relative dimensions of Serpent (fig. 3; C) with its long blank side facade, and wall anchors on the Molenpoort side. This building was notably large for the area, with an extended structure and seven fireplaces, suggesting its previous use as a malt house and inn. With its long main building, the structure was above average in size in comparison with the surrounding properties. The entire complex must have been thirty m deep, exceptional dimensions for a house.

A. Nieuwe Kerk

B. Oude Langendijck;

C. Serpent house

D. Trampolen house

E. Molenpoort

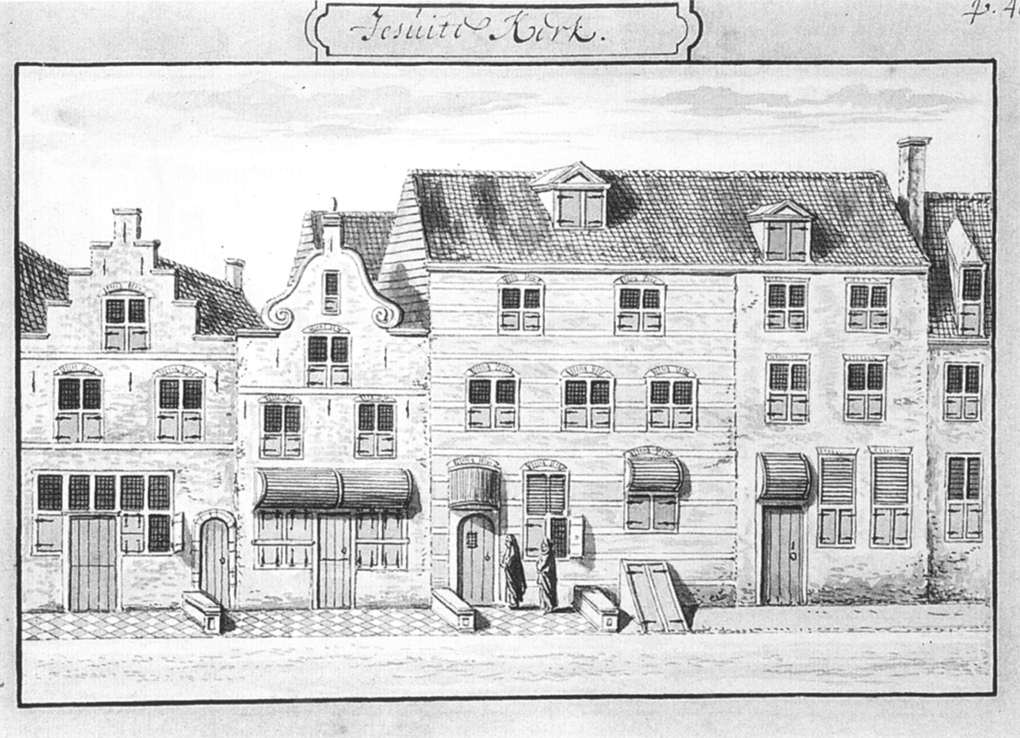

The belief that Vermeer lived in the Serpent stemmed from Van Peer’s assertation that identified the house as owned by a certain Jan Tin, later corrected to Jan Geensz Thins by Montias, who believed that Maria Thins and her family rented this house from the Jesuit fathers and allowed Catharina and Johannes to move in after 1653.John Michael Montias, "Chronicle of a Delft Family," in Vermeer, edited by Albert Blankert, Gilles Aillaud, and John Michael Montias, (Woodstock and New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2007), 45. This hypothesis was widely accepted in Vermeer literature for fifty years. Montias maintained that the Thins house is pictured in an eighteenth-century drawing (fig. 4) of Jesuit church on Oude Langendijk by Abraham Rademaker (1677–1735), an eighteenth-century painter and printmaker from the Northern Netherlands, as furthest house immediately to the right, or the house outside the drawing to the right.

Abraham Rademaker

c. 1670

Brush and gray ink, 13.2 x 20.2 cm.

Gemeentearchief, Delft

But Slager, who focused only on archival data and details, provided a detailed rescontruction of the Oude Langendijk and Burgwal areas. According to Slager, Thins family owned neither of the corner houses of Molenpoort. There is, he claims, no deed of purchase; nor has any lease agreement survived. The illegality and seclusion of the Catholic community would have meant that many transactions were arranged privately among neighborhood residents, without the involvement of an official, usually Protestant party, such as a notary, lawyer or orphan chamber, so that little or no information has survived in the Delft archives. Slager’s archival research involved an in-depth reanalysis of old data, adding new information that Vermeer may have resided in the smaller Trapmolen house on the west corner.Earlier deeds record the house had a rosmolen (horse driven mill) that likely lay behind it.

Slager discovered that in 1641, Jan Geensz Thins had actually purchased a different building than either the Serpent or the Trampolen, which was not the corner building. Additionally, 1667 municipal records for the corner building reveal that the "quay tax"In the 17th century Netherlands, a "quay tax" was a type of levy or tax imposed on properties located adjacent to a canal or waterway. The term "quay" refers to a platform lying alongside or projecting into water for loading and unloading ships. In Dutch cities like Amsterdam or Delft, which were characterized by their extensive canal networks, properties lining these canals were often subject to this tax. The quay tax could be based on several factors, including the length of the property's frontage along the canal, its size, or its use. The rationale behind this tax was likely twofold: firstly, properties on the canal benefited from their prime location, offering easy access for trade and transportation, and secondly, maintaining the canals and adjacent areas (like quays and bridges) was costly, and these taxes helped fund their upkeep. was paid not by Geensz Thins or Maria Thins, but by owner Pieter van der Dussen, scion of a wealthy Delft Catholic family, who had bought the Serpent house before 1656.5 This, according to Slager, invalidates the most important argument in favor of the house on the east corner as Vermeer’s home.

Slager's research reveals that while the Serpent has a width of a little over seven meters, the Trapmolen (fig. 3; D) was nearly four and a half meters wide. According to the oldest Delft cadastral map, from 1823, the plot was about seventeen metres long. With room for a small courtyard, as indicated in the 1676 inventory, this leaves a length of about thirteen meters for the house, which is less than half the length of the Serpent, but still sizable for a residential house. The difference in size between the Serpent and the Trapmolen across the alley is clearly visible on the Kaart Figuratief. The map shows a front house with a small rear house, behind which lies a small courtyard that opens onto the Molenpoort. Prominent features include the two chimneys on the main building, the windows and the billboard on the Molenpoort and the position of the front door – today all the way to the right of the facade—which in keeping with seventeenth-century usage is still located in the center.Serpent was legally owned by Pieter van der Dussen but in practice, like Trapmolen and other houses in the Papist corner, was bought for the Jesuit mission to use and rent out. The earliest image of the Trapmolen, giving a clear picture of the building, dates back to 1858 and was produced by Leiden lithographer and draughtsman Christiaan Bos.

According to Slager, the rooms and household effects recorded in Vermeer’s 1676 probate inventory fit comfortably in the present corner building.H.G. Slager, "Vermeer’s House Revisited" (Ommen, 2018), online paper, Essential Vermeer. The successive quarters also match the inventory drawn up following the death of a cloth merchant, who died in the house in autumn 1801. While the house now has an eighteenth-century facade and the side facade along the alley shows later brickwork and newer windows, its shape and ground plan still provide a good picture of the situation when Vermeer lived here.Both Ab Warffemius and Henk Zantkuijl have also made attempts in the past to draw the layout of the house in 3-D based on Vermeer's inventory after his death- Kee Kaldenback, instead attemtped the same taks with Trapmolen.. See: Kees Kaldenbach, with contributions by Allan Kuiper and Henk J. Zantkuijl, "Working towards a Reconstruction of Johannes Vermeer's Home at the Oude Langendijk, Delft," accessed December 28, 2023, https://kalden.home.xs4all.nl/vermeer-info/house/h-a-reconstructie-ENG.htm.

While recent researchers like Hans Slager and Pieter Roelofs have suggested Trapmolen as the likely residence, in the article "Finding Vermeer: Back to the Molenpoort," the art historian Frans Grijzenhout presents new archival evidence to argue that Groot Serpent was indeed the house rented by Vermeer's mother-in-law, Maria Thins, and where Vermeer lived and worked.

Grijzenhout utilizes historical tax records, particularly the "Groot Familiegeld" register from 1674–1675, to trace the tax collector's route and analyze the sequence of residents along Oude Langendijk. This analysis demonstrates that Maria Thins was listed as residing on the eastern corner, confirming that she lived in Groot Serpent rather than Trapmolen. The size, status, and higher rent of Groot Serpent align with Maria Thins's wealth and social standing, making it a more plausible residence for the extended Thins-Vermeer household, which included Vermeer, his wife Catharina Bolnes, and their numerous children.

Additionally, the article clarifies the location of the Jesuit church in Delft, correcting previous misconceptions and confirming its proximity to Groot Serpent. By establishing that Vermeer lived in Groot Serpent, Grijzenhout emphasizes the significance of Vermeer's social ambitions and his integration into a wealthy Catholic family, which likely influenced his artistic career. The spacious and well-situated residence provided Vermeer with an ideal environment for his work as a painter and art dealer, reflecting the spatial, social, and cultural milieu that shaped his life and art until the economic downturn following the French invasion in 1672.

In response to Frans Grijzenhout's claim that Johannes Vermeer lived in Groot Serpent, Slager ("Vermeer’s house again and the Jesuit Church") defends his original position that Vermeer's residence was more likely Trapmolen, located on the western corner of the Molenpoort. He critiques Grijzenhout's reliance on the 1674 "Groot Familiegeld" tax ledger to place individuals in specific houses, arguing that the ledger's incomplete data and assumptions about non-owners residing in certain properties lead to unreliable conclusions.

Slager points out that several of Grijzenhout's placements of individuals along the Oude Langendijk are based on conjecture rather than solid evidence. He highlights inconsistencies and errors in Grijzenhout's sequential method of assigning residents to houses, emphasizing that key figures like Jannetje Stevens and the Van Swieten sisters were likely residing in different locations than those proposed by Grijzenhout. Regarding the location of the Jesuit church, Slager argues that Grijzenhout's analysis is based on incorrect house widths and a misreading of historical documents. He provides new archival data to support his original assertion that the church was situated in the fourth and fifth houses east of the Molenpoort, not the second and third as Grijzenhout suggests.

In conclusion, Slager maintains that Grijzenhout's arguments do not provide sufficient evidence to revise the likelihood that Vermeer's house was Trapmolen on the western corner of the Molenpoort. By re-examining tax records, property ownership documents, and other archival sources, Slager reaffirms his earlier findings about the locations of both Vermeer's residence and the Jesuit church. He underscores the importance of careful analysis and corroboration of multiple sources when reconstructing historical settings, suggesting that Grijzenhout's conclusions are not sufficiently grounded to overturn the existing understanding of Vermeer's living situation in Delft.

Inside Vermeer's House

According to the inventory, Vermeer's house had eleven rooms including kitchens, a cellar, a courtyard and an attic. The considerable size of the house places it among the larger dwellings in Delft. Each room had a different function which was not always the case in Dutch houses. Living and working space in houses of the common folk were not clearly defined as yet.

On the ground floor we find a large room, grote zaal or "opkamer" in Dutch, which gave onto a small room, a mezzanine, four kitchens (one for cooking and one for doing wash) and a cellar which was evidently on the basement level. A group of family portraits, religious objects and Vermeer's civic guard pike and helmet indicate the representational function of the grote zaal. There were also two rooms on the first floor and an attic above.

MICROSOFT'S Search Maps

The contents of these rooms was not what would be termed luxurious. Some of the objects were worn and of little value. Instead, the wardrobe of the Vermeer family was more than adequate although seriously lacking if compared to the wardrobes of the rich Delft burgers. Several jackets or coats belonged to Vermeer and a few fur-lined jackets (the type which we see in the compost ions of Vermeer) were owned by his wife Catharina. Clothes were extremely expensive and that the poor had scarcely one of each basic type of garment at best.

"Most houses in Dutch towns are built closely together. They are aligned in such a way that light only enters the house from either the street side or from the garden side. That is why the painter's studio would be located at either end of the house. In any street which runs from east to west, northern light can be found on either the garden side of the northern block of houses—or at the street side of the southern block of houses. This is obvious on such streets as the Choorstraat in Delft on which a remarkable number of artists lived."The information of this paragraph was drawn from the website site dedicated entirely to Vermeer house and its original furnishings: Kees Kaldenbach, with contributions by Allan Kuiper and Henk J. Zantkuijl, "Working towards a Reconstruction of Johannes Vermeer's Home at the Oude Langendijk, Delft," accessed December 28, 2023, https://kalden.home.xs4all.nl/vermeer-info/house/h-a-reconstructie-ENG.htm.

Life at Vermeer's house must have been very different, if not the opposite of what the artist so often chose to represent in his perfectly balanced interiors where just a few elegant figures "dialogue in silence." Catharina Bolnes, Vermeer's wife, gave birth to fifteen children, an exceptionally high number in the Netherlands where two or three were considered normal. One can only dare imagine all the work that Catharina had to do to maintain a minimum of decore: child-care, cooking, mending and cleaning. Some critics have imagined that Vermeer's household was in reality far more similar to one of the famous interiors of Jan Steen (c. 1626–1679) rather than his own.

Vermeer's studio was located on the upper floor. He could look out directly on the Mart and observe the bustling civic life of Delft The windows of Vermeer's studio faced north. This was the direction that painters always preferred because the light from the north is cooler and, above all, more consistent throughout the day. It is probable that Vermeer also employed two smaller rooms on the same floor for his profession. The attic was used for storing painting equipment such as a large slab of stone used for grinding paint. The inventory of the top floor also lists two painter's easels, three palettes, six panels, ten canvases, three bundles with all sorts of prints, a high reading desk and here and there rummage not worthy of being itemized separately.

In all, about twenty-five books of all kinds were found, a sign of social distinction. Books were owned by about two or five percent of the Dutch population.

The list of cooking and eating utensils was substantial. No knifes and forks are listed but the use of these particular utensils was not widespread at the time. The furnishing of house of Vermeer was more than adequate but not luxurious.

Click here to visit the website of Kees Kaldenbach for detailed information about the house of Vermeer.

Click here to access a Detailed house-by-house study of Vermeer's neighborhood

(with ample database), which gives an alternative location for Vermeer living quarters by Hans G. Slager.

click on the thumbnails below for more hi-res images of the Oude Langendijk.