The Art of Painting

De Schilderkonst)c. 1662–1668

Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm. (47 1/4 x 39 3/8 in.)

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

inv. 9128

The textual material contained in the Essential Vermeer Interactive Catalogue would fill a hefty-sized book, and is enhanced by more than 1,000 corollary images. In order to use the catalogue most advantageously:

1. Scroll your mouse over the painting to a point of particular interest. Relative information and images will slide into the box located to the right of the painting. To fix and scroll the slide-in information, single click on area of interest. To release the slide-in information, single-click the "dismiss" buttton and continue exploring.

2. To access Special Topics and Fact Sheet information and accessory images, single-click any list item. To release slide-in information, click on any list item and continue exploring.

The gilt chandelier

A period chandelier in the Delft Stadhuis (Town Hall)

Nowhere in Vermeer's oeuvre has iconographic interpretation proven as intricate as in The Art of Painting. Experts generally believe the glistening golden chandelier crowned by a double-headed eagle, the imperial emblem of the Habsburgs, alludes to a prior era when that dynasty governed the Netherlands. This association could connect it with the vertical crease in the map (created prior to the wars and Treaty of 1648), which emphasizes the divisions between the Spanish South and the independent Northern United Provinces.

One critic proposed that the eagle might symbolize sight allegorically, representing one of the five senses intended to enhance the painter's focus. It has also been interpreted as an emblem of the phoenix, symbolizing a reborn and reunited Netherlands.

Regardless of its iconographic significance, it's difficult to conceive that Vermeer, arguably the most "optical" artist of the Netherlands, wasn't drawn to the significant technical challenge it posed to his vision and craftsmanship. The highlights are painted with remarkably thick, opaque dabs of light-toned paint, seemingly dancing atop the painting's surface to mimic the glimmer of sunlight.

Prof. Willemijn Fock, a Dutch historian, pointed out that such chandeliers allowed artists to showcase their skill in capturing the shimmering and refractive qualities of brass under varying lighting conditions. Nevertheless, multi-branched chandeliers were seldom found even in the homes of the wealthiest citizens (usually one at most). In the few inventories where chandeliers are mentioned, they are referred to as "kerkkroon" (church chandeliers), as this type was more frequently hung in churches or civic buildings than in residences.

Vermeer's contemporary painter Gerrit ter Borch repeatedly employed a very similar chandelier as a prop in his compositions, although he never bestowed as much attention to it as Vermeer did.

The hanging tapestry

Woman at the Clavichord

Gerrit Dou

c. 1665

37.7 x 29.8 cm.

The Trustees of

Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

From a purely visual perspective, the drawn-back tapestry functions as a so-called repoussoir, a technique to achieve perspective or spatial contrasts by placing a large figure or object in the immediate foreground, to the left or right. By only partially covering the map, the trumpet and the still life, Vermeer prompts the viewer to pull back the tapestry completely, engaging them not only visually but also physically in the painted illusion. The pervasive illusionism in The Art of Painting is rooted in a strong grasp of perspective and an understanding of optical principles.

Vermeer likely knew of the renowned contest from Greek antiquity between painters Parrhasius and Zeuxis to determine who was superior. Pliny the Elder recounted this tale in his Naturalis historia, 77 A.C., drawing from a Greek source. Zeuxis created a still life so convincing that birds descended from the sky to peck at the painted grapes. Parrhasius then asked Zeuxis to draw back the curtain in his painting. When Zeuxis realized the curtain was part of the painting and not real, he had to admit defeat. While his work deceived the eyes of birds, Parrhasius had fooled the eyes of human beings.

A popular anecdote suggests that Rembrandt's students once painted coins on his studio floor, amusing themselves as they watched him bend down to try and pick them up.

Dutch painters working on themes similar to Vermeer had already pioneered and perfected the curtain device years before him. Gerrit Dou, the renowned fijnschilder, incorporated such curtains in a few of his more ambitious compositions.

The wood rafters

Willem Weve, a Delft architectural historian, observes that although domestic construction was not standardized in the city during the mid-17th century, the type of ceiling depicted in this painting is one of several arrangements used in houses, and surviving examples can indeed be found. The timber members are small beams, likely made of pine, supported by a wall plate over the windows, as seen at the top left in The Music Lesson. It is probable that the beams were supported at their other ends on a wall which would be on the right of Vermeer's pictures, although it remains out of sight. The ceiling beams in Vermeer's Music Lesson, Allegory of Painting and Allegory of the Faith can all be observed sloping downwards from left to right. The consistent slanting in these three cases implies the potential that this is a physical characteristic of the room rather than an inaccuracy in Vermeer's drawing.

The map of the Netherlands

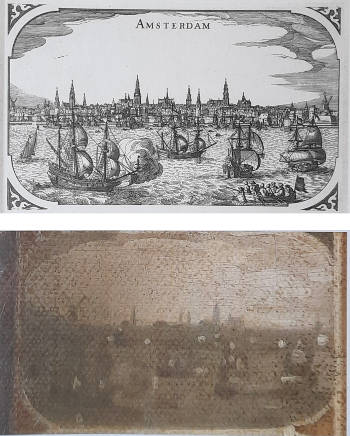

Various painters represented this same map of the Netherlands in their compositions. The city views and title scripts were each printed separately and then affixed together, just as the nine separate sections composing the map's body were assembled. The city views could be associated with the notion that a successful painter bestows fame and glory upon the cities of their birth, a concept highly valued in Vermeer's era. Interestingly, Vermeer's hometown, Delft, is absent from representation. However, the two lateral strips of town views found in The Art of Painting distinguish it from the works of other artists.

It's intriguing that Vermeer, who was at the zenith of his artistic prowess, merited only a brief mention in Beschryvinge der Stadt Delft (Description of the City of Delft), published in 1667 by Dirck van Bleyswick. In contrast, other painters, now considered less significant, received lavish praise. Ironically, Van Bleyswick also lamented that the fame due to great artists often arrives only after their passing. Positioned precisely to the left of the standing Clio is a view of the Hof in The Hague, the governmental seat of the Seventeen Provinces.

The map of the Netherlands

Various painters represented this same map of the Netherlands in their compositions. The city views and title scripts were each printed separately and then affixed together, just as the nine separate sections composing the map's body were assembled. The city views could be associated with the notion that a successful painter bestows fame and glory upon the cities of their birth, a concept highly valued in Vermeer's era. Interestingly, Vermeer's hometown, Delft, is absent from representation. However, the two lateral strips of town views found in The Art of Painting distinguish it from the works of other artists.

It's intriguing that Vermeer, who was at the zenith of his artistic prowess, merited only a brief mention in Beschryvinge der Stadt Delft (Description of the City of Delft), published in 1667 by Dirck van Bleyswick. In contrast, other painters, now considered less significant, received lavish praise. Ironically, Van Bleyswick also lamented that the fame due to great artists often arrives only after their passing. Positioned precisely to the left of the standing Clio is a view of the Hof in The Hague, the governmental seat of the Seventeen Provinces.

The female figure on the top of the cartouche

The female figure atop the cartouche symbolizes the "unity and separation" of the Seventeen Northern and Southern Provinces. She holds the coat of arms of the North and South in her left and right hands, respectively.

The chairs

A number of unused chairs populate Vermeer's interiors. Some critics have supposed that they allude to someone missing from the scene. In this picture, the chair seems to have a function as a repoussoir device to augment the illusion of depth.

The two red velvet, ochre-fringed chairs in this painting, known as "Spanish chairs" appear identical to the one in the foreground of Vermeer's Woman with a Pearl Necklace. Walter Liedtke has suggested that the foreground chair may have been provided for a hypothetical connoisseur visiting the artist's studio. Perhaps the second background chair was included to offer the observer a comparison of relative sizes to enhance the sensation of depth. However, the drawing is inadequate making it appear to lean to one side and creating an unsual effect of clutter as it clashes with the legs of the painter's easel.

The term "Spanish chair" refers to a style of furniture that was popular during the 17th century in Europe, particularly in Spain and the Netherlands. These chairs are characterized by their distinctive design, which often features leather or textile upholstery, a rectangular or square backrest, sometimes with armrests that curve downward and outward. The legs of Spanish chairs are usually turned or carved, adding to their ornamental appeal. Spanish chairs gained their name from the association with Spanish design and were inspired by the furniture styles of the Spanish court and aristocracy. They were known for their comfort and elegance, making them sought-after pieces of furniture in wealthy households.

The inscription inside the decorative cartouche of the map

When this map was created, the official separation and resulting peace of the Northern (today's Netherlands) from the Southern Provinces (today's Belgium) that it represents was about to be formalized. The map may be seen as an extensive panorama of the military history of the war of liberation of the Seventeen Provinces from Spanish rule. The inscription inside the decorative cartouche addressed the map's military theme: "The tremendous wars waged in these countries in bygone days, and still waged in these days, bear sufficient witness to the whole wide world of the great strength, power and wealth of these very countries." Naturally, this inscription cannot be read on Vermeer's representation.

The map: made for sale

Only one complete original print of this map has survived. It was discovered in the double bottom of a chest that had been locked for years, in "Skokloster," a house built by the Swedish admiral Wrangler, near Uppsala in Sweden. Vermeer's map includes a title band on the top, a series of town views along the sides, which frame the central part of the map. The central part was printed with nine separately engraved sheets. 17th-century catalogs advertised maps that could be purchased "with or without their ornamentation." A single map could be composed in several ways, making it a made-to-order work of art, and some makers offered custom hand coloring. Very few wall maps of this kind have survived, even though catalogs, inventories, interior paintings and other documents tell us that they must have been printed in great numbers. All the maps in Vermeer's painting were printed in Amsterdam, which was then one of the principal centers of map-making in the world.

Other painters, including Jacob Ochtervelt and Nicolas Maes, appear to have used the same map six times in their paintings. Only in Vermeer's painting do we find it attached with the vertical series of town views.

The artist at his easel

The Artist in His Studio (detail)

Rembrandt van Rijn

c.1629

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Vermeer's easel was identical to those represented in countless Dutch paintings of artists' studios, such as the one pictured in an early self-portrait by Rembrandt. The crossbar on which the painting is poised could be lowered and raised by a very simple system of pegs and holes. Some critics have noted that the left-hand leg of the easel seems to have been omitted as it approaches the tiled floor. However, if one carefully projects the upper contours, it can be seen that in reality, it fits snugly, unseen, behind the two left legs of the stool on which the painter is seated.

The tradition of depicting painters at work in their studios stretches far into the 20th century. In his masterpiece Las Meninas, Diego Velázquez portrays himself in the act of painting while also including a reflection of King Philip IV and Queen Mariana in a mirror behind him. In Self-Portrait with Dr. Arrieta, Francisco Goya portrays himself at his easel, accompanied by his friend Dr. Arrieta. Edgar Degas' The Artist's Studio showcases a cluttered artist's studio with figures engaged in various artistic activities, including a self-portrait of the artist at his easel. Decades later, Pablo Picasso painted several self-portraits in his studio with an easel.

A self portrait?

Although Vermeer specialists do not believe that The Art of Painting was conceived primarily as a self-portrait, there is no reason why the artist would not have wished to leave at least some testimony of himself and it is certainly not the self-portrait that appeared at the Amsterdam auction in 1696, in which 21 paintings by Vermeer were sold. However, the question of whether Vermeer is depicted in it remains a favorite topic of speculation. as one critic commented," if he is portrayed, it's possible that even his best friend might fail to recognize him." The intentional nature of this mystification cannot be denied. The only discernible features are those of the Italianate mask, a detail that holds as much meaning as we choose to attach to it.

Nonetheless, the artist's long, soft hair that gracefully flows out from under the beret may have been his own. The manner in which it blends imperceptibly into the colors of the background is one of the most suggestive and technically challenging but least noticed passages of the work.

It has been remarked more than once that the black beret, despite its realistic appearance, has been barely modeled. Simple berets of this kind were, and still are, considered a typical attribute of painters. There exist other paintings in which the artist turns his back towards the viewer, but only rarely do they completely conceal his face. The viewer must imagine what he looked like.

The humble beret, with its origins dating back to classical times, has evolved into a symbol of the artist for multiple reasons, deeply intertwined with history and cultural perceptions. Berets offer practicality through their easy wear and portability. Artists can effortlessly don them, making them ideal for those engrossed in their creative work. Additionally, the beret's simple design complements a diverse range of artistic styles and personalities. The beret's significance extends to contemporary cultural and political movements. Its enduring popularity within artistic circles mirrors artists' aspirations to epitomize the spirit of artistic freedom and the unconventional essence associated with the bohemian lifestyle.

Self-Portrait)

Willem van Mieris

c. 1705

Oil on canvas, 92.5 x 75.5 cm.

Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden

During the 17th century, self-portraiture became a significant genre in Dutch art.

With the decline of religious and royal commissions due to the Protestant Reformation and the decentralization of the Dutch Republic, artists were forced to cater to a growing middle-class clientele. Self-portraits were relatively inexpensive to produce, as they didn't require a model.

Many artists painted self-portraits as a form of self-promotion. Displaying their skill in capturing likenesses, details, and emotions, artists showcased their talents to potential clients. Think of it as an artist's version of a resume or portfolio, although self-portraiture was also as a form of introspection, immortalizing their image and their place in the world. It became a space for experimentation, where the artist could experiment with poses, lighting, costume and setting, pushing the boundaries of the genre. Art dealers and collectors, recognizing the skill and potential value, purchased self-portraits both as investments and for personal appreciation. Moreover, mutual admiration among artists meant that they often bought, traded, or were gifted self-portraits of their peers.

The young model

Specialists generally agree that the demure young model represents Clio, the muse of history, as described in Cesare Ripa's 16th-century book of emblems and personifications, Iconologia. Translated into Dutch in 1644, Ripa's volume was widely consulted by history painters. Vermeer also used it for at least one other allegorical painting, the late Allegory of Faith.

Clio's crown of laurel denotes glory and eternal life. Her trumpet signifies fame. The thirst for fame was considered a fundamental stimulus to artistic production. By placing Clio at the center of his allegory, Vermeer emphasizes the importance of history to the visual arts. Theorists argued that the highest form of artistic expression was history painting, which comprised biblical, mythological, historical and allegorical subjects. Curiously, Vermeer himself practiced true history paintings only at the outset of his career. By placing this allegory in a contemporary setting, he may have wished to prove that the lofty values of history painting could also be achieved when represented in modern settings. In any case, The Art of Painting demonstrates that Vermeer was aware of the major artistic debates that circulated among the cultural elite of the time.

History, obviously, was related to the concept of fame. The ancient Greek artists understood that their work held potential as a vehicle for fame, and by the fourth century B.C., they had begun to incorporate their own likenesses into their works. The self-portrait served as a prominent and sophisticated signature for artists like Phidias, who, for example, included his image in the guise of a warrior on the massive cult statue of Athena in the Parthenon. Even Plutarch, writing on the most distinguished names in Greek history in his Lives, notes Phidias' great fame and how his works "brought envy."

The trumpet

Title page of the English

edition of Iconologia by Cesare Ripa

The young woman, who represents the muse of history Clio, holds in one hand a trumpet and in the other a large book, perhaps a volume by Thucydides or Herodotus. Vermeer portrays the back side of the volume where one would not expect to see an inscription, thus avoiding the risk of becoming overtly didactical and precluding our purely visual enjoyment of the work.

The trumpet stands for fame. In Samuel van Hoogstraten's Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst (Introduction to the Art of Painting, 1678), an image of Clio is depicted, almost exactly as described in Cesare Ripa's Iconologia, a famous early iconographic dictionary that was widely used by painters of historical and allegorical subject matter.

The trumpet was used copiously in many other paintings of the time and after. The Spaniard Diego Velázquez incorporated symbolic elements into his artwork, as seen in Las Meninas, where a little princess holds a miniature trumpet, symbolizing her role in the Spanish royal court and her future authority, while also hinting at the significance of her image being captured in the painting, reinforcing the theme of artistic representation.

Nicolas Poussin, on the other hand, employed the trumpet to convey divine authority and revelation. In The Resurrection of the Body an angel holds a trumpet, symbolizing the biblical concept of resurrection and the announcement of divine truths.

In Pierre Mignard's The Coronation of the Virgin, angels holding trumpets are present in the scene, symbolizing the grandeur and sacred nature of the moment, and carrying connotations of heavenly announcement and spiritual elevation. Closer to home, Jan Steen, the Dutch painter and contemporary of Vermeer, portrayed the trumpet in some of his genre painting as a playful element, often suggesting the lively atmosphere of a festive scene. It adds a touch of joyful exuberance to his compositions, emphasizing the celebratory nature of the depicted events.

The artist's costume

A Cavalier (self portrait)

Frans van Mieris

1657–1659

20 x 16 cm.

Collection Art Gallery of New South Wales

Dutch costume expert Marieke de Winkel challenges the long-held idea that the artist's peculiar dress was outdated and meant to reflect bygone times. Although this kind of slashed doublet was not universally worn, it was nonetheless an item of contemporary dress. This fashion had occurred in earlier times and had become popular again in the 1620s and 1630s but had reached its extreme form in the 1660s, when Vermeer made The Art of Painting.

Vermeer's choice of such an elaborate and historical costume was deliberate. By claiming an affiliation with the earlier Netherlandish painters, he was literally trying to step into their shoes. He modeled himself on his illustrious Northern predecessors rather than on an aristocratic gentiluomo or poet or even less the rags and poverty of the dissolute self-portraits that had become very popular in the Netherlands. Artists, especially successful ones, evidently enjoyed dressing themselves up in similar fanciful garments, such as a self-portrait by Vermeer's contemporary Frans van Mieris.

Other painters, such as Eglon van der Neer, Caspar Netscher and Gabriel Metsu, depicted very similar garments. By Vermeer's time, they were referred to as "innocents," a term which also means "retarded" or "simpleton," most likely because they had become so short and revealed so much of the undergarment that they appeared somewhat foolish. Thus, it seems likely that this does not place the artist outside his time, but as Eric Jan Sluiter noted, "beyond the ordinary, which is fitting for a figure representative of this honorable art."

It was not uncommon to draw on costumes painted in the past. Painter and art writer Karel van Mander recommended the prints of Lucas van Leyden as an excellent resource for historic costumes. "In these, as with all his other prints, one sees pleasant variations of faces and costumes after the old styles: hats, caps and headdresses which for the most part differ one from another, so that in Italy the great masters of our own time have been able to profit greatly from his works in that they have borrowed from them and applied things in their own works, with occasional small variations."

Did Vermeer use a camera obscura?

The debate over whether Vermeer employed a camera obscura—an optical device that artists could use to project images onto a canvas, aiding them in achieving realistic details—remains ongoing. Some art historians propose that Vermeer might have utilized it, pointing to the meticulous details and lighting in his paintings. However, since the camera obscura doesn't leave a tangible trace of its usage, others contend that Vermeer's techniques relied more on his skill and artistic intuition.

This device, a marvel of its time, was well-known to painters and scholars familiar with optical principles and light behavior. References to similar devices can be found in writings of the era, including those by Dutch Renaissance figure Constantijn Huygens and the painter-art writer Samuel van Hoogstraten. Johannes Kepler, in the early 17th century, also mentioned a similar concept. A significant hint of camera obscura use in The Art of Painting is seen in the blurred portrayal of the drapery over the table's edge. The painting's main focus was further in the background. This optical phenomenon, termed depth of field, where not all parts of an image are in focus, is not noticeable in normal vision due to the eye's rapid refocusing. Experiments with period camera obscuras demonstrate similar effects when soft materials are viewed out of focus.

The large book

The inclusion of this large bound volume may support the idea of art theorists that painting was a liberal art and that the painter was an educated intellectual on the level of poets and philosophers, rather than a lowly craftsman. Leonardo da Vinci's introduction to his Treatise on Painting reads: "Painting has every right to complain of being driven out from the number of Liberal Arts, since she is a true daughter of nature and employs the noblest of all the senses. It was wrong, oh writers, to leave her out from the number of Liberal Arts, because she deals not only with the works of nature but extends over an infinite number of things which nature never created."

The debate about painting's place among the liberal arts, known as "il Paragone," which translates to "comparison" in Italian, was a significant topic of discussion during the Renaissance and beyond. This debate revolved around comparing the status and merits of different artistic disciplines, particularly painting and sculpture, with the classical liberal arts such as grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy.

Throughout history, this debate played out in writings, artworks and artistic treatises. Artists sought to emphasize the intellectual aspects of their craft, often using allegorical and mythological subjects to showcase their ability to convey complex ideas through visual means.

The plaster cast on the table

In the Studio (detail)

Michael Sweerts

1652

73.5 x 58.8 cm.

Detroit Institute Museum of Arts, Detroit

This curious, large-scale plaster mask has always intrigued scholars. Some have proposed that it symbolizes the art of painting through its association with the painter's academic training. Drawing from plaster casts of antiquity, considered "more perfect than nature," was a fundamental requirement of an artist's training. The Accademia di San Luca in Rome (founded in 1593) devised a curriculum to combat the decline of art (Caravaggio and his followers who practiced painting directly from nature) which was based on drawing from classical sculpture, perspective, anatomy and foreshortening. The evident foreshortening in Vermeer's rendering of the mask may allude to this form of training.

It is also possible that the mask alludes to the so-called il paragone, or the comparison of the arts (see Special Topics below) although it has also been associated with the concept of transience.

Recently, art historian Sabine Pénot has noted that "a headband runs above the eyebrows, which blends into a diadem-like element, such that the top of the cast is pointed." She suggests that, taking into account that the head is in direct contact with the brilliantly lit triangle of the background wall and its elusive gossamer rendering, it can be associated with Apollo, the god of light, which might be reasonably made. Leonaert Bramer, the most respected artist in Delft at the time with whom Vermeer had close contacts, had elevated painting to the Liberal Arts in the decorative program of the new Delft Guild of Saint Luke in which Apollo and the art of painting were united.

The detail to the left of Michael Sweerts' An Artist in his Studio (1652) shows a young painter in front of two plaster casts of classical sculptures of faces similar to the ones in Vermeer's Art of Painting.

The painter's tools

Self Portrait

Michiel van Musscher

c. 1665–1667

47.6 x 36.8 cm.

Vienna, Liechtenstein Museum

Most experts believe that in The Art of Painting Vermeer had not intended to reveal significant information about his own working methods. For example, both the artist's palette and chest with drawers, which would have contained the rest of the necessary materials, are both conspicuously absent.

Vermeer's seated painter applies paint in full color directly to the top of the canvas where the laurel leaves are represented. Instead, we know that after the initial drawing Vermeer, like most fine painters of his school, blocked in the basic forms and lighting of his composition with brownish pigment. Successively, color was added. This monochrome stage is known as underpainting and was widely employed by Northern painters of the time, especially among artists whose drawings and compositions were very elaborate.

Perhaps the only detail which accurately reflects Vermeer's working methods is the so-called maulstick, or painter's stick. The maulstick was a standard piece of 17th-century studio equipment and served to steady the artist's hand for detailed work while distancing it from the wet paint on the underlying canvas. In Vermeer's death inventory, one maulstick was noted among the equipment of his studio. The painter in Rembrandt's Artist in His Studio of around 1629 holds one as well .

The text on the top of the map

To identify the source for the map in The Art of Painting, we need not look beyond the painting itself. A lengthy Latin inscription found at the top of the map (partially obscured by the chandelier) may be read as follows: NOVA XVII PROV[IN]CIARUM [GERMANIAE INF]ERI- [O]RIS DESCRIPTIOI ET ACCURATA EARUNDEM ...DE NO[VO] EM[EN]D[ATA]...REC[TISS]- IME EDIT[AP]ERNICOLAUM PISCATOREM. Thus, the origins of the map (designed with north to the right), which shows the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands (Germania Inferior), can be attributed to Nicolaus Visscher (Nicolaus Piscator).

The text on the top of the map

To identify the source for the map in The Art of Painting, we need not look beyond the painting itself. A lengthy Latin inscription found at the top of the map (partially obscured by the chandelier) may be read as follows: NOVA XVII PROV[IN]CIARUM [GERMANIAE INF]ERI- [O]RIS DESCRIPTIOI ET ACCURATA EARUNDEM ...DE NO[VO] EM[EN]D[ATA]...REC[TISS]- IME EDIT[AP]ERNICOLAUM PISCATOREM. Thus, the origins of the map (designed with north to the right), which shows the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands (Germania Inferior), can be attributed to Nicolaus Visscher (Nicolaus Piscator).

The folio that hangs from the table

The large, thin folio which hangs over the edge of the table has been variably interpreted as an architectural drawing folio or music manuscript even though its present state of conservation does not permit it to be identified with certainty. In a carefully composed and articulated allegory such as The Art of Painting, it appears odd that Vermeer would have left its meaning unclear. Some critics have also understood it as being a large folio containing preparatory drawings which the artist would have consulted while working. Painters frequently made many drawings from nature which were used during the actual painting process as models. Few painters actually painted directly from life.

In conjunction with this manuscript, Vermeer specialists have noted that in the inventory of Vermeer's house taken after the artist's death, were listed "five books in folio size; another 25 books of all kinds." Unfortunately, none of the books were identified. The draping page, which barely touches the artist, plays an important role in linking the figure of the painter and his model, who would have been physically divided and hence thematically isolated.

The illuminated sliver of white-washed wall

The blade-like form of this brilliant patch of white wall energizes the entire composition. Its effect is even more pronounced when the painting is observed directly. The irregularities produced by the notable paint build-up and the vigorous brushstrokes add sparkle to the pure white paint (white lead). Prepared artificially since the earliest historical times and used until the nineteenth century, this warm white is very opaque, has outstanding brushing qualities and mixes well with every color on the artist's palette. As its name suggests, lead white is a by-product of lead, and whatever the form of manufacture used, the purity of the color depends on the purity of the lead. White lead produced in the Netherlands was particularly prized. In the "Dutch" or "stack" process, strips of lead rolled up into spirals were placed in closed earthenware jars containing acetic acid, and the pots were then buried under tanner's bark or dung; the heat evolved by fermentation aids in the formation of white lead through an increase in carbonic acid. Very soon a thin coat of white coating forms. The white lead is then washed and thoroughly cleaned. White lead is extremely poisonous and must be handled with care, but its mechanical behavior cannot be substituted by other pigments even though today it has been entirely supplanted by titanium white, preferred for its cooler tone and superior covering power.

The marble floor tiles

Because these splendid marble floors can be seen in most genre pictures from the middle and the third quarter of the 17th century, we are led to believe that they were a standard feature in nearly all well-to-do interiors. Typically, they were only found, if at all, in the entrances or corridors of the most opulent homes. Vermeer, while in Delft, might have encountered stone-tiled floors in a few sections of the Town Hall. But to come across an actual marble floor, Vermeer would have needed to visit the grand Rijswijk palace. So, it is doubtful that Vermeer could have directly observed and painted this type of marble tile in his own studio.

Willemijn Fock, a historian of the decorative arts, has shown that floors paved with marble tiles were extremely rare in Dutch 17th-century households, and that only in the houses of "the very wealthy where floors of this type were sometimes found, they were usually confined to smaller spaces such as voorhuis, corridors and upper-story sleeping or storage rooms." Fock reasons that the almost countless representations of these floors in Dutch genre painting may be explained by the fact that artists were attracted by the challenge involved in representing the difficult perspective of receding multicolored marble tiling and the appreciation of perspective effects among art collectors and connoisseurs. In any case, the scarcity of marble floors was due to their elevated cost and the chilly sensation they provided compared to wooden flooring.

The garments in the painting

Clothing has the power to convey many meanings in painting. In formal portraiture, great importance was given to the dress to suit the ideals or culture of the sitter. Although the fanciful styles of past centuries often come to mind when we think of 17th-century painting, the vast majority of formal portraits show sitters in "normal" dress. Occasionally, more original types opted for the so-called "portrait historié" in which the sitter or sitters sported garments and fashion accessories of historical figures of the past, diverse and remote as those as Anthony and Cleopatra. Through the portrait historié, one might proclaim his affinity with virtues of classical times.

The painter generally had little to say about the sitter's choice of dress. Through his art, he manipulated the appearance of the tuck, fold, textural qualities and lighting to convey his own aesthetic concerns. Sometimes, prevailing fashions, such as the typical black clothing of the early 17th century, left the artist few opportunities to indulge in the finer points of his craft. Fanciful, expensive dress and even jewelry might be lent to the painter for the more extravagant portraits. Back in the studio, the artist would duplicate the lighting, pose and dress of the sitter with the aid of a life-size mannequin so that the complex patterns of folds would not be altered every time the sitter moved.

The standing model, dressed in blue silk and a long cream-colored silk gown, personifies Clio, the muse of history, a figure drawn from classical Greek literature. The billowing blue wrap, casually draped over her shoulders, does not belong to contemporary fashion. It was meant to recall the Antique and links Vermeer's composition to a central tenet whereby a great work of art brings fame to both the artist and his city, a theme already dear to the ancient Greeks. The figure's long silk gown with three black bands along the lower border, instead, appears to be a contemporary garment seen in similar versions many times in interior genre painting of the time.

Various art writers have linked the silk garments in Vermeer's compositions to his father's dealing with caffa (a mixture of silk and cotton or wool adapted for dress and upholstery). But one only has to look at the hundreds of interior paintings of the time to understand that they were one of the most characterizing elements of the school. We can only reason that such garments were both highly desirable objects in themselves and an important calling card for potential art buyers. Gerrit ter Borch, one of the finest genre painters of the time, established his flourishing career on his uncanny ability to render every nuance of silk.

The table

Hiding in the deep foreground shadows of some interiors by Vermeer is a sturdy draw-leaf table, called a balpoottajel or trektajel in Dutch. From its origin at the beginning of the 17th century, the draw-leaf table evolved from a solid everyday object into a richly ornamented showpiece. One of the most characteristic features of the draw-leaf table is its bulbous spherical legs, which are most clearly visible in Vermeer's Art of Painting. Rather than waste an extremely thick piece of wood, the cabinet maker added wood blocks to all four sides of each leg before turning them. Thus, the leg was thickened only at the position of the ball. This process also reduced the chance of splitting the wood. The stretchers between the legs strengthen the table. In the first half of the 17th century, they form a rectangle; in the second half of the century, the stretcher moved to the middle of the table with a V-shaped connection at the two ends, a so-called double-Y form. The tables that appear in Vermeer's paintings appear to have the stretchers of the later type.

This information was drawn from Frederik J. Duparc et al, Golden: Dutch and Flemish Masterworks from the Rose-Marie and Eijk Van Otterloo Collection (New Haven;Yale University Press, 2011)

special topics

- The "Mapmaking Impulse"

- Vermeer in his Studio?

- The Artist's Studio & Artistic Inspiration

- Fame & the Art of Painting

- Vermeer & the Liefhebbers van de Schilderknost (art lovers)

- Il paragone: The Superiority of Painting

- Self Portraits of Dutch Painters in their Studios

- A Free Lesson in Painting Technique

- A Very Ambitious Painter

- The Art of Painting & Adolf Hitler

- Listen to Period Trumpet Music

The signature

signed on the map, behind Clio's collar: IVerMeer

(Click here to access a complete study of Vermeer's signatures.)

Dates

1662–1665

Albert Blankert, Vermeer: 1632–1675, 1975

c. 1666–1667

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer, London, 2000

c.- 1666–1669

Walter Liedtke Vermeer: The Complete Paintings, New York, 2008

c. 1667–1668

Wayne Franits, Vermeer, 2015

c. 1666–1668

Pieter Roelofs & Gregor Weber, VERMEER, Amsterdam, 2023

(Click here to access a complete study of the dates of Vermeer's paintings).

Technical report

The support is a plain weave linen with a thread count of 11.1 x 16.5 per cm². Cusping shows that the canvas was secured to the strainer with 11 (wooden?) nails at the sides and 9 at the top and bottom. The canvas was lined with a glue lining and stretcher construction probably from the 19th century.

Recent examination has detected the date, applied by the artist, immediately following his signature, and can be interpreted as MDCLXVI(I I ?). The lettering is consistent with selected inscriptions in both The Astronomer (1668) and especially The Geographer (1669). A signature of Pieter de Hooch, applied in the 18th century, is still present and can be clearly seen through infrared reflectography, positioned along the lower cross support of the artist's stool.

The ground is made of a single (principal) layer containing coarsely ground lead white with admixtures of chalk, ochre, umber and charcoal black. The color of the ground is a mid-level, somewhat neutralized, gray-brown. Earlier binding media analysis of the preparation layer in the Vienna canvas suggested that it contains both protein (glue) and drying oils (mixed). Recent analysis reveals that the dominant medium for the ground is linseed oil.

The x-ray of the painting does not reveal any detectable changes in composition. Examinations with infrared reflectogram reveal that the initial modeling of the forms is constructed through the characterization of the shadowed areas first.

Fine black lines of underdrawing have been detected, defining the contours of various design elements, for example, at the arms of the chandelier, the framing of the single city views in the wall map or the easel.

The vanishing point of the complex composition is marked with a pinhole just under the knob at the left edge of the map. Recent examination has detected a second deformation (similarly positioned at the right side of the map) that acts as a vanishing point for the stool upon which the artist is sitting.

Yellow earth, umbra, or ochre was detected within the leaves of the tapestry with indications of additional ultramarine in areas of shadows. Lead tin yellow is the primary pigment present in the chandelier—most likely together with lead white (subsequently glazed)—or with pure lead tin yellow. Lead tin yellow has been detected for the highlights of the chair tacks and umbra or ochre for the border fringe. Ochre is the chief pigment in the book Clio is holding.

A copper (soap) based underpainting (verdigris) can be seen covered with a semi-transparent layer of ultramarine, for the teal-covered textile draped from the table at left. Ultramarine has been detected in the blue of the ships within the right side of the map and the veining in the marble floor. The leaves within the tapestry would originally have a stronger green coloration. The color was almost certainly made with the admixture, or application of, an organic-based glaze that was light or solvent-sensitive.

Vermilion was found as the pigment for the leggings of the painter. Additionally, a possible red organic glaze over a medium brown under-layer within the tapestry can be seen.

Charcoal (vine) black is used almost exclusively, except for one area where a pentimento in the right shoe of the painter is located. Here bone black is the principal pigment. Copper is found as an admixture as well as iron oxide in the paints of the painter to lend a warmer tone.

present condition:

In the early 1950s, following a traveling exhibition from the Kunsthistorisches Museum's paintings collection, considerable adhesion problems with minute flaking above all in the lighter areas were noticed. The first in-depth study concerning the delicate condition of the painting was made 1994/95 in connection with the large Vermeer-exhibition of 1995/96 in Washington and The Hague. The examinations of the binding medium, ground and paint layers revealed an oil-rich tempera mixture with additions of small amounts of proteinaceous material used by Vermeer to render the lighter-colored passages in the painting. In addition to the resins, gums and proteins, detected in the overlying coatings, this resulted in increased mechanical forces. The process of flaking seems to resist under stable conditions but was activated by external (climatic and mechanical) factors.

see: Robert Wald, "The Art of Painting. Observations on Approach and Technique," 312–321, and Elke Oberthaler, Jaap J. Boon et al., "The Art of Painting by Johannes Vermeer. History of Treatments and Observations on the Present Condition," 322–327, in: Vermeer. Die Malkunst. exh. cat. ed. by Sabine Haag, Elke Oberthaler, Sabine Pénot. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna 2010.

Provenance

- The artist's widow, Catharina Bolnes (1675–1676);

- transferred to her mother, Maria Thins (24 February, 1676);

- evidently sold at auction in Delft, 15 March, 1677;

- possibly Baron Gerard van Swieten, prefect of the Imperial Court Library, Vienna (d.1772);

- his son, Gottfried van Swieten (d. 1803);

- his estate, as by Pieter de Hooch (1803–13, sold to Czernin);

- Count Johann Rudolf Czernin (1813–34, as by De Hooch);

- by descent to Count Eugen Czernin (d.1955) and Jaromir Czernin (d.1966);

- Adolf Hitler (1940–1945); Munich Central Collecting Point (1945);

- transferred on 17 November, 1945 to the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, in 1958 to the museum's permanent collection (inv. 9128).

Exhibitions

- Zurich October 1946–March, 1947

Meisterwerke aus Oesterreich

Kunsthaus

no. 426 - Brussels April–June, 1947

Art Treasures from the Vienna Collections

no. 148 - Amsterdam July–October, 1947

Art Treasures from the Vienna Collections

no. 193 - Paris November 1947–March, 1948

Art Treasures from the Vienna Collections

no. 193 - Stockholm May–October 1948

Art Treasures from the Vienna Collections - Copenhagen December 1948–March 1949

Art Treasures from the Vienna Collections - London 12 May–3 September, 1949

Art Treasures from the Vienna Collections

Tate Gallery

no. 191 - Washington D.C November 20, 1949–January 22, 1950

Art Freasures from the Vienna Collections

National Gallery of Art

34, no. 124 and ill.. color, plate iv, as "The Artist in his Studio" - New York February–May, 1950

Art Freasures from the Vienna Collections

Metropolitan Museum of Art

34, no. 124 and ill. color, pl. iv, as "The Artist in his Studio" - San Francisco July–October 1950

Art Freasures from the Vienna Collections

M.H. De Young Memorial Museum

34, no. 124 and ill.. color, plate iv, as "The Artist in his Studio" - Chicago November 9,1950–January 19, 1951

Art Freasures from the Vienna Collections

The Art Institute of Chicago

34, no. 124 and ill.. color, plate iv, as "The Artist in his Studio" - St Louis March 4–April 22, 1951

Imperial Vienna Art Treasures

Saint Louis Art Museum - Toledo May–June, 1951

Art Freasures from the Vienna Collections

Toledo Museum of Art - Toronto August–September, 1951

Art Freasures from the Vienna Collections - Boston October, 1951–January, 1952

Art Freasures from the Vienna Collections

Museum of Fine Art. - Philadelphia February–April, 1952

Art Freasures from the Vienna Collections

Philadelphia Museum of Art - Oslo May–July 1952

Art Freasures from the Vienna Collections

no. 176 - Innsbruck August–November, 1952

Art Freasures from the Vienna Collections - Vienna 1953

Österreichs Amerika: usstellung "Kunstschätze aus Wien"

Kunsthistorisches Museum

no. 264 - Zurich 1953

Hollander des 17. Jahrhundert

Kunsthau

no. 173 - Rome January 4–February 14, 1954

Mostra di pittura olandese del seicento

Palazzo delle Esposizioni

90, no. 177 and ill. in cover, as "L'atelier" - Milan February 25–April 25, 1954

Mostra di pittura olandese del seicento. Palazzo Reale

90, no. 177 and ill. in cover, as "L'atelier" - Delft/Antwerp 1964–1965

De schilder in zijn wereld: Van Jan van Eyck tot Van Gogh en Ensor

Stedelijk Museum Het Prinsenhof, Delft/Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

no. 113 (shown in Delft only) - Paris September 24–November 28, 1966

Dans la lumière de Vermeer

Musée de l'Orangerie

no. IX - Washington D.C November 24, 1999–February 8, 2000

Johannes Vermeer's The Art of Painting

National Gallery of Art - New York March 8–May 27, 2001

Vermeer and the Delft School

Metropolitan Museum of Art

no. 76 - London June 20–September 16, 2001

Vermeer and the Delft School

National Gallery

no. 76 - Madrid February 19–May 18, 2003

Vermeer y el interior holandés

Museo Nacional del Prado

178–181, no.38 and ill. - The Hague 25 March–26 June, 2005

De Weense Vermeer, een bijzonder bruikleen (The Vienna Vermeer, an exceptional loan)

Mauritshuis - Tokyo August 2–December 14, 2008

Vermeer and the Delft Style

Metropolitan Art Museum

184–188, no. 30 and ill. - Vienna 25 January–25 April, 2010

Vermeer: The Art of Painting

Kunsthistorisches Museum

no. 1 and ill.

(Click here to access a complete, sortable list of the exhibitions of Vermeer's paintings).

The "mapmaking impulse"

In the groundbreaking The Art of Describing, Svetlana Alpers declared that the interpretation of maps in Vermeer's paintings merely as symbols was a too restrictive point of view. An overlooked but vital characteristic of Dutch culture and its art, she suggested, is "the mapping impulse." Thus, the map hanging on the wall—so perfectly rendered that it has no equal in Dutch painting—is filled with multiple meanings. First, it is a "powerful pictorial presence" which catches the viewer's attention in many ways. The details are so specific that the particular map can be identified. It is large, with many visual components, including lettering, pictures and the lines of the map itself. Finally, Vermeer placed his signature on it. In all these ways, Vermeer likened the painting to the map and, by extension, the act of painting to the act of map-making. For Alpers, this similarity reveals something essential about the Dutch idea of painting.

The Music Lesson (detail)

Jacob Ochtervelt

1671

Oil on canvas, 80.2 x 65.5.

Art Institute of Chicago

In reference to the connection between painting and mapmaking, Alpers wrote: "The aim of Dutch painters was to capture on a surface a great range of knowledge and information about the world. They too employed words with their images. Like the mappers, they made additive works that could not be taken in from a single viewing point. Theirs was not a window on the Italian model of art but rather, like a map, a surface on which is laid out an assemblage of the world."

A similar but not identical map of the United Provinces appears in the background of a contemporary work by Jacob Ochtervelt. However, as usual in Dutch art, it is delineated with scarce attention to the physical properties of the map itself and functions more as compositional filler.

Marjorie Munsterberg, "Historical Analysis," (Writing About Art, 2008–2009), http://writingaboutart.org/pages/historicalanalysis.html.

Vermeer in his studio?

In 1696, two decades after Vermeer's death, twenty-one of the artist's "excellent and artful paintings" were sold in an Amsterdam auction, presumably collected by Pieter van Ruijven and inherited by his son-in-law Jacob Dissius. In the sales catalogue, item number 3 was described as "the portrait of Vermeer in a room with various accessories, uncommonly beautifully painted by him." This painting was sold for the relatively low price of 45 guilders, scarcely twice more than that of the tiny Lacemaker in the same auction. Thus, few experts believe it corresponds to The Art of Painting, which is many times larger and a far more ambitious composition. In fact, most agree that Vermeer's intention was not so much to make a lasting effigy of himself, but rather to commemorate and define the role of the artist in history and his association with fame through the use of symbols which in those times must have been readily understood by the cultural elite to whom this image was destined.

Perhaps, this description suggests that Vermeer depicted himself in a comparable context, as seen some years later in a portrait of the Amsterdam painter Michiel van Musscher that was probably painted after Vermeer's model,

Fame & the art of painting

Clio

Pierre Mignard

1689

143.5 x 115 cm.

Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

In our own times, when art is often accorded merit on the basis of its presumed originality, it is difficult to imagine a time when artists and writers regularly consulted a book of iconography before starting work. Ever since antiquity, artists sought to convey abstract ideas in visual forms through the use of symbols that could be readily deciphered by individuals of equal cultural standing. Iconologia, originally compiled by the Italian Cesare Ripa in the late sixteenth century, is such a work.

One recurrent question that occupied painters concerned the artist's place in society. Should he be considered a craftsman, on par with carpenters and goldsmiths, or a creative genius, such as poets and philosophers? Another concern was that the great artist could bestow eternal fame on his city or nation through his work.

In The Art of Painting, Vermeer presumably addressed both issues by portraying an allegorical figure, Clio, the muse of History. In antiquity, Clio was one of the nine muses, personifications of the highest aspirations of art and intellect in Greek mythology. The Muses were the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, the Titan goddess whose name means memory. When the Romans later separated the muses' fields of inspiration, Clio became the patron of history. Her antique symbols are a laurel wreath and a scroll.

In Vermeer's painting, Clio is portrayed as a girl with a crown of laurel that denotes glory, a trumpet and in her left arm, she cradles a large yellow volume, presumably Thucydides' Histories. Thucydides' volume can be seen in an etching contained in Samuel van Hoogstraten's Inleyding tot de Hooge Schoole der Schilderkonst, published 1678. Van Hoogstraten believed paintings should strive to become a universal science that could represent all things visible.

Il paragone: the superiority of painting

Allegory of Painting and Sculpture

Guercino

1637

Oil on canvas, 114 x 139 cm.

Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome

Scholars believe that Vermeer's Art of Painting addressed a number of weighty issues that regarded both the art of painting in particular and the fine arts in general. One of them was the so-called il paragone, or the comparison of the arts.

In the past, there was an enduring and impassioned debate concerning the hierarchical status of the various arts. In the Quattrocento, Italy was the battleground on which painters, still handicapped by the classical prejudice against manual labor, fought to establish their art on the higher tier of the Liberal Arts. At the time, practicing painters, in fact, were relegated among artisans and craftsmen. The rivalries between painting and poetry and painting and sculpture were particularly intense although in the course of the Renaissance, the kinship between painting and poetry became commonplace so much that they were considered sister arts by some.

Having worked in sculpture and painting, the great Leonardo da Vinci claimed the right to judge the value of each. While painting could imitate sculpture, sculpture could not imitate painting. Furthermore, "painting is the more beautiful and the more imaginative and the more copious, while sculpture is the more durable but it has nothing else." For Leonardo, the limitation to poetic expression lies in its use of verbal language alone: "Painting comprehends in itself all the forms of nature, while you have nothing but words, which are not universal as form is, and if you have the effects of the representation, we have the representation of the effects," that is, one word after another; painting, vice versa, renders the whole of a scene immediately evident through a single image. The artists and scholars who celebrated painting's superiority over sculpture cited painting's ability to imitate and surpass nature, but perhaps most importantly, its ability to deceive nature itself. Furthermore, it offered a kind of permanence that contrasts with the fleeting nature of music.

By Vermeer's time, the debate still raged and had been extended to science as well. It was argued that doctors and astronomers can know the visible world through the use of acquired skills, but artists can not only comprehend the natural world but also replicate it. The painter's art embraces and recreates the entire visible world, or as in the words of painter and art theorist Samuel van Hoogstraten, "the Art of Painting is a science for representing all the ideas or notions that visible nature in its entirety can produce, and for deceiving the eye with outline and color."

Deception, as we know, was at the heart of Vermeer's concept of illusionist painting and perhaps nowhere more manifest than in his monumental Art of Painting.

Portraits of artists in their studio

Although Dutch art abounds in self-portraits of artists in their studio, it is difficult to ascertain how true to life they were to real circumstances. Two conventions in the depiction of artists in their studios dominated the 17th-century art market; both were a subtle blending of fact and fiction.

On one hand, history painters, steeped in the memories of classical models, strove to convey an idealistic view of their profession, assuming the traditional guise of the learned gentleman artist as fostered by Renaissance culture. Artists depicted themselves surrounded not only with the tools of their trade but also crowded with seemingly irrelevant props and even mythological figures brought in and arranged for the occasion to communicate specific concepts about their art through the use of symbolism and allegory. A perfect example of this mode of self-portraiture is Vermeer's own Art of Painting.

The Artist in His Studio

Rembrandt van Rijn

c.1629

Oil on panel, 24.8 x 31.7cm.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

However, in the 17th-century Netherlands, a startling new development in self-portraiture began to rival the classical model and became one of the most salable subject matters of all. Painters presented themselves in a more unseemly light than those of the glorious past.

Dropping the noble robes of the pictor doctus, they smoked, drank, wore rags in dilapidated studios and chased women. The Dutch artistic literature of the 17th century was rife with interesting, often comical anecdotes about artists' personal lives and working methods, which kindled the public's imagination and appetite for images. Dutch artists explored a new mode of self-expression in "dissolute self-portraits," as Ingrid A. Cartwright called them, embracing the many behaviors that art theorists and the culture at large disparaged.

Cartwright wrote that dissolute self-portrait also reflects and responds to a larger trend regarding artistic identity in the 17th century, notably, the stereotype "hoe schilder hoe wilder" (if painter, then crazy). Artists embraced this special identity, which in turn granted them certain freedoms from social norms and a license to misbehave.

Self-portraits of dissolute artists were extremely popular with the public since they not only portrayed the artist but were considered a specimen of the artist's exceptional talent and a manifestation of his original character. Modern art historians now believe that the numerous self-portraits by Rembrandt were intended as much a response to this trend as the inner need for self-introspection.

Listen to period music

![]() Two Trumpet Duets, Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber

Two Trumpet Duets, Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber

Natural trumpet made by Paul Hainlein,

Nürnberg 1666

National Music Museum, Vermillion, South Dakota

The trumpet, one of the oldest instruments, is already mentioned in the Bible (the "trumpets of Jericho" or the "trumpets of the Last Judgment"). Its ancient precursors were widespread in Africa and Europe and were principally made from ivory, animal horns, or shells (triton) or tree-bark shavings. Long straight metal trumpets were used in the ancient Egyptian culture both for signaling but moreover as cult- and symbolic instruments demonstrating the royal power of the Pharaohs. Two of these instruments, made of silver and bronze, were found in the tomb of Tutankhamun (1333–1323 B.C). Similar functions can be traced to the ancient Greek and Etrusco-Roman empires (called there "Salpinx," "Tuba," "Lituus," or "Buccina") as well as in the Byzantine era.

After the fall of the Roman empire, the trumpet disappeared from Europe and was reintroduced in the Middle Ages, when the Crusaders took them from the Saracens as war booty and soon became widespread in Europe. The trumpet's most important functions were the military signaling in the battles and the signaling of power and status, as only a king was allowed to have trumpeters at his court.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Royal Trumpeters and Kettledrummers held a privileged position at the Habsburg court in Vienna and were the first to get the rights of founding a guild, unique in the Holy Roman Empire. The guild regulated the number of trumpeters and ensured the trumpet's exclusiveness by restricting where it could be played and by whom.

Other courts, like that of the Emperor of Saxony in Dresden or that of the Bishop of Olomouc in Kremsier (today Kroměříz, Czech Republic) as well as the courts in Bologna and London, were well-known for their orchestras, especially for the splendid sound of their trumpet choirs. Some of the most renowned trumpet players (P. Vejvanovský, G. Fantini) and composers (J.H. Schmelzer, H.I.F. Biber, J.J. Fux) wrote intricate compositions for the trumpet or complete brass choir.

Trumpets were also used for the warning of fire or other dangers, like the approach of enemies. The so-called "waits," a group of trumpeters and shawm-players, observed the area from the church towers or other central towers to communicate any danger to the bell ringers, watchmen and the citizens in general. Later their task became a more ceremonious and decorative adjunct of civic life, providing musical entertainment at official city proceedings. J.S. Bach appreciated the important tradition of the "Turmblasen" by the municipal "Stadtpfeifer" in Leipzig. Until today a military music corps, consisting mainly of brass instruments, above all trumpets, plays on all official state ceremonies.

The form of the natural trumpet, which had been developed in the late Middle Ages, was a twice-folded or closed S-shape, consisting of three yards, with a bell-shaped flare of exact mathematical proportions. The mouthpiece, as the supporting sound generator, is inserted into the first yard. The joint of the first two sections is concealed under a tightly fitted cover which in the Baroque period had a ball-shaped decoration surrounding it. This ball, called the "boss," is not a merely decorative element but strengthens the joint that attaches the bell to the rest of the instrument and serves as a grip to hold the instrument. The mouthpiece has to support and contain the vibrating membrane, i.e. the player's lips, and to produce a complementary edge-tone.

The natural trumpet is able to produce only the notes of the harmonic series. The sound of the trumpet is generally produced by blowing air through closed lips to produce a "buzzing" effect through vibration with the support of the mouthpiece. The player can select the pitch from a range of harmonic series or overtones by altering the amount of muscular contraction in the lip formation, supported by a certain tongue manipulation.

A free lesson in painting technique

Boy Blowing Bubbles (detail)

Frans van Mieris

1663

26 x 19 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

Although the picture of Vermeer's artist's studio is a far cry from the real working conditions of a Dutch painter, the artist nonetheless shares with the modern viewer one of his "trade secrets." Near the top of the canvas, the painter has begun depicting the model's laurel wreath in fluid brushstrokes. Curiously, the leaves are colored blue instead of the deep green one would expect. This was not a mistake.

It should be remembered that 17th-century painters had a handful of pigments, a fraction of those available to any artist today. One of the most serious lacunae of his palette was a deep, stable green, indispensable for rendering foliage. Dutch painters remedied this by employing a technique called glazing. First, the area intended to be green was modeled in shades of blue. Once thoroughly dry, the same area was painted over with a syrupy mixture of a transparent yellow pigment and drying oil, usually linseed or poppy oil. This glaze, as it was called, produces an exceptionally natural, deep green without concealing the dark and light modeling beneath and was utilized extensively by Dutch still-life painters. By altering the intensities and proportions of the blue underpainting and the yellow glaze, a wide range of natural greens could be produced which were not available as single pigments.

Unfortunately, this method sometimes had negative consequences. The yellow glaze, if not properly executed or exposed to detrimental environmental conditions, is prone to fade. The foliage in Vermeer's own Little Street has suffered from such a malady. A spectacular example of this defect can be seen in Frans van Mieris' Boy Blowing Bubbles.

A very ambitious painter

Much has been written about Vermeer's professional and social aspirations. Although his family background would be described today as lower-middle-class—his grandparents were illiterate, and so was his mother—from what we can piece together from his painting and a few clue documents, Vermeer was ambitious.

The Delft artist demonstrated throughout his career the willingness to disengage himself from his original social standing and define himself as an artist/gentleman. On the other hand, many Dutch artists were more than content to churn out less-than-original paintings and, as long as they received adequate pay, were not adverse to considering themselves artisans.

Vermeer married the daughter of a well-to-do Delft patrician, which entailed a significant move from the lower, artisan class of his Reformed parents to the higher social stratum. His mother-in-law seems to have had a discreet art collection and family connections with a few noted Dutch painters. Archival evidence shows that in 1654, the artist is mentioned for the first time as "Meester-schilder" (Master painter), indicating he had by this time improved his professional and social status. By 1655, the "Sr" (signior or seigneur) preceding Vermeer's name in an archival document is a sure sign of the artist's improved social status. Vermeer's father was never distinguished in such a way in any of the numerous documents which regard him. Furthermore, Vermeer was elected various times to head of the St. Luke Guild of Delft. In 1663, the French diplomat Baron Balthasar de Monconys visited his studio, most likely acting on advice from Constantijn Huygens, one of the foremost connoisseurs of Dutch art as well as an influential politician, musician and poet.

However, the most graphic indication of how Vermeer defined his position as an artist is manifested in his show-case piece, The Art of Painting. In this work, the artist identifies himself with an elitist spiritual and intellectual role of the artist rather than the workaday life of the artisan. Few of the real painter's tools, which would suggest the manual status of the artist, are visible, while many of the props denote "inspirational" value and awareness of the issues connected with the art of painting.

Historically, one's occupation was evaluated on the basis of its proximity to or distance from physical labor since manual work had been associated with slavery in antiquity. Though early Renaissance artists were certainly not considered slaves, their mechanical labor ranked them firmly on the lower side of the cultural divide.

From about 1400, artists attempted to elevate their status in society. Renaissance painters strove to qualify not only as themselves but the entire profession as members of the Liberal Arts, seizing on self-portraiture to help them prove their point. This was done by stressing the intellectual components in art and its production, emphasizing the artist's inherent genius and recasting the artist as a member of the social and artistic nobility as well as a part of the "reflected glory" of famous artists in history.

In an effort to prove painting's superiority to sculpture, Leonardo da Vinci argued that painting involved less physical effort than sculpture. Sculpture "causes much perspiration which mingles with the grit and turns to mud." The sculptor's face is "pasted and smeared all over with marble powder, his dwelling is dirty and filled with dust and chips of stone." The painter, on the other hand, "sits before his work at the greatest of ease, well dressed and applying delicate colors with his light brush." His home is "clean and adorned with delightful pictures," and he enjoys "the accompaniment of music or the company of the authors of various fine works." Vermeer's Art of Painting could not have been too far from what Leonardo had in mind.

The Art of Painting & Adolf Hitler

"Monuments Man" Lt. Daniel Kern and mine

worker Max Eder inspect The Art of

Painting, found inside the mine at Altaussee.

Adolf Hitler wanted Vermeer's Art of Painting for one of his most ambitious projects: the giant art museum he planned to create in Linz, his Austrian birthplace. In 1940, he purchased it for 1.65 million Reichsmarks from Jaromir Czernin, the brother-in-law of Austria's prime minister from 1934 until Austria was annexed by Germany in 1938. The painting had been in Czernin's family since the 19th century.

Hitler saw Vermeer as the embodiment of the great artist he desired. The Art of Painting was to be one of the main attractions in the new Führer Museum in Linz, which he intended to fill with the art he had looted from all over Europe. At the end of the war, American troops found it stashed in a vault with a handful of other masterpieces in an Austrian salt mine, along with thousands of other plundered works, including Michelangelo's Bruges Madonna and Vermeer's own Astronomer. In the final months of the war, after Hitler issued his famous Nero Decree calling for the destruction of all German infrastructure, orders were issued by the local Nazi gauleiter to destroy the artworks by blowing up the mines. His plan was foiled because lower-echelon Nazis saw no reason to ruin a perfectly good salt mine and, instead, decided to destroy the entrance to the cave.

The Czernins began petitioning the Austrian government for the restitution of the painting in the 1960s, without success. The government argued that the sale was voluntary and the price adequate. The family has now come back with a study of the sale that they claim shows that it was made under duress.

Vermeer & the "Liefhebbers van de Schilderknost" (art lovers)

Art-lovers in a Painter's Studio (detail)

Pieter Codde

c. 1630

38 x 49 cm.

Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart

By the time Vermeer depicted The Art of Painting, he must have been well introduced to the circle of connoisseurs and art dealers that counted. In those times, there existed no international museum circuit, no slew of art magazines and no enthusiastic public lined up in front of every blazoned art exhibition, but a small, fervent and essentially elitist assembly of "Liefhebbers van de Schilderknost," or Lovers of the Art of Painting.

Art lovers and artists frequented one another in the hushed privacy of the artist's studio, not at public art exhibitions, debates, or auctions as they do today. Artists could advance their social standing by being associated with influential art lovers who inevitably belonged to society's upper crust, while the art lovers had the opportunity to hone their knowledge of the arts, which was a central requisite for any self-respecting gentleman. In the oft-quoted Essays on the Wonders of Painting, Pierre le Brun advises readers that to "discourse on this noble profession, you must have frequented the studio and disputed with the masters, have seen the magic effect of the pencil (brush), and the unerring judgment with which the details are worked out."

This symbiotic relationship between artist and art lover can be traced back to the Renaissance, which had reexamined numerous passages in classical literature about artists. For example, Pliny had described the visit of Alexander the Great to Apelles' studio. The roster of Titian's clients reads like a list of international society in the 16th century: the Duke and Duchess of Urbino, Alfonso d'Este, Duke Federigo of Mantua, Ippolito de' Medici, several ancient and cunning Popes, doges, admirals, art dealers, intellectuals. Even those who were deadly enemies, like Francis I of France and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, had in common the fact of having been painted by Titian. In 1533, Emperor Charles V appointed Titian court painter and elevated him to the rank of Count Palatine and Knight of the Golden Spur. This was an unprecedented honor for a painter, and Ridolfi tells a revealing anecdote concerning the respect Titian was accorded even by the emperor himself: Titian dropped a brush, and when Charles picked it up for him, he protested "Sire, I am not worthy of such a servant," to which the emperor replied, "Titian is worthy to be served by Caesar."

Promoted by writers like Baldassare Castiglione in his influential Il Cortigiano (1528), it became fashionable for rulers to patronize the arts and personally frequent the great artists of the time. Later, major Dutch painters like Rembrandt, Gerrit Dou and Frans van Mieris had all made inroads to aristocratic doors. Vermeer himself had a tight relationship with Pieter van Ruijven, who had acquired the title of Lord of Spalant for a colossal sum, evidently in order to style himself along the lines of the great patrons of the past.

Portrait of Pieter Teding van Berckhout

Casper Netscher

Oil on copper

Teding van Berckhout Foundation

Evidently, Vermeer's studio must have been one of the destinations for art lovers of the time. On May 14, 1669, Teding van Berckhout, an up-and-coming regent from Delft, had arrived in Delft to visit Vermeer's studio. Duly impressed, he returned a month later and wrote in his diary, "I went to see a celebrated painter named Vermeer" who "showed me some examples of his art, the most extraordinary and most curious aspect of which consists in the perspective." Van Berkhout had arrived in Delft accompanied by Constantijn Huygens and his friends, member of parliament Ewout van der Horst and ambassador Willem Nieupoort. The cosmopolitan Huygens was an artistic authority in his own day, maintaining contacts with the famous Flemish painters Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck and recording in his own diary some remarkably insightful comments about the art of, among others, Rembrandt van Rijn.

Six years earlier, a well-connected Catholic French diplomat Balthasar de Moncony, probably on Huygens' advice, had also visited Vermeer's studio. He registered his disappointment in his diary as follows: "In Delft, I saw the painter Verme(e)r who did not have any of his works: but we did see one at a baker's, for which six hundred livres had been paid, although it contained but a single figure, for which six pistoles would have been too high a price."

Simply put, De Monconys thought the painting he saw was worth less than a tenth of the price mentioned. Unfortunately, he made no mention of the style and quality of such works. It appears he judged them exclusively on the basis of the number of hours required to do the work. The price of six hundred livres that the baker—presumably Van Buyten—thought reasonable for his painting corresponds to the six hundred livres that Dou had asked from de Monconys two days earlier for his Woman at a Window, clearly also a work with only one figure.

That Vermeer did not suit de Monconys' tastes is less significant than the fact that in prominent circles, the artist's studio was considered on par with those of the most renowned Dutch artists.

The artist's studio & artistic inspiration

A Painter in his Studio, Tuning a Lute

Pieter Codde

signed and dated, 162[9?]

Oil on panel, 41 x 54 cm.

Private collection

* The theme of the artist in his studio was beloved by the Dutch painters of the Golden Age. The painter Pieter Codde was among those who favored it, having depicted studio scenes in which art lovers are portrayed studying paintings, artists are in a state of contemplation, or in discussion with visitors or clients. Musical instruments were frequent props in such scenes. A particularly interesting variation on the subject is Pieter Codde's recently discovered A Painter in his Studio, Tuning a Lute, which represents a painter tuning his lute in front of an empty canvas. This particular combination of objects alludes to the finding of inspiration—the most essential part of the artistic process—in front of the empty canvas, the tabula rasa, which may be understood as a visual counterpart of popular anecdotes such as the one about the Dutch painter Gerard de Lairesse (1640–1711), as told by Arnold Houbraken in his Groote Schouburgh.

The anecdote recounts that upon de Lairesse's arrival in Amsterdam, the noted art dealer Gerrit Uylenburgh had the artist sit in front of an empty canvas (een ledigen doek) to witness the artist's exceptional talent. Asked by Uylenburgh when he wanted to start, de Lairesse responded, "what would you want me to paint?" The subject was to be of the artist's choice, after which Uylenburgh gave him the necessary painting materials. De Lairesse then sat down, pulled out a violin from underneath his mantle and played a little tune on it, after which he took his chalk and drew in one go a whole stable with beasts, Joseph, Mary and her Child. He then played some more, and before the afternoon had finished, he had painted nearly the whole scene, to the amazement of all. Codde's rendition is likewise an allusion to artistic inspiration and creativity, a candid opportunity for the beholder to witness this mysterious process, and as such represents an ode to the art of painting itself.