Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

(Brieflezend Meisje bij het Venster)c. 1657–1659

Oil on canvas, 83 x 64.5 cm. (32 3/4 x 25 3/8 in.)

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

(Old Masters Picture Gallery), Dresden

inv. 1336

The textual material contained in the Essential Vermeer Interactive Catalogue would fill a hefty-sized book, and is enhanced by more than 1,000 corollary images. In order to use the catalogue most advantageously:

1. Scroll your mouse over the painting to a point of particular interest. Relative information and images will slide into the box located to the right of the painting. To fix and scroll the slide-in information, single click on area of interest. To release the slide-in information, single-click the "dismiss" buttton and continue exploring.

2. To access Special Topics and Fact Sheet information and accessory images, single-click any list item. To release slide-in information, click on any list item and continue exploring.

The green trompe l'œil curtain

Flower Still Life with Curtain

Adrian van der Spelt and Frans van Mieris

1658

Oil on panel, 46.5 x 63.9 cm.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

The most straightforward example of trompe l'œil (French; fool the eye) in Vermeer's oeuvre is this green satin curtain. Observed carefully, the curtain does not belong to the implied space of the three-dimensional room. It hovers slightly over the painted surface hung from a curtain rod that runs just below the upper border of the composition. In real Dutch households, this kind of curtain was employed to protect precious paintings from dust or for covering nudes. The trompe l'œil curtain was also a favorite illusionist trick among painters of the Delft School.

By the time Vermeer painted this work, the trompe l'œil curtain had been amply exploited. Rembrandt van Rijn was the first Dutch painter to include a sculpted frame as well as a curtain pulled aside in 1648. It was a favorite device among the fijnschilderen like Frans van Mieris or Gerrit Dou of Leiden whose goal was to paint works so realistic that they could not be distinguished from reality. An astounding example of the curtain trompe l'œil can be seen in the collaborative effort by Van Mieris and Adrian van der Spelt.

Both Dou and Van Mieris, in fact, had been compared by contemporaries to Parrhasios, the painter of Greek antiquity who in a contest was able to fool Zeuxis, another Greek painter. The story goes that Zeuxis had painted a still life with grapes so persuasively that birds had descended upon it to peck them. Parrhasios, however, had included a curtain on one side of the composition that Zeuxis unwittingly attempted to pull back to see the entire painting. While Zeuxis had fooled birds, Parrhasios had fooled a man.

Surprisingly, the trompe l'œil curtain was not a part of Vermeer's original design and was added most likely for compositional motives. It hides a so-called roemer, or drinking glass, that stands upright on the far right-hand side of the table. Although trompe l'œil devices may appear somewhat naive today, Vermeer's contemporaries would have been less quick to realize the artifice.

A Cupid: lost and found

The Love Letter (detail)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1667–1670

Oil on canvas, 44 x 38.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

It has been long know from x-rays and infrared radiograph images that on the background wall, just above and to the right of the young woman, Vermeer had included a large-scale ebony-framed painting of Cupid (the same one that appears in A Lady Standing at a Virginal. But it was universally held that was painted it out by the artist himself, before the work left his easel. However, as a result of the latest investigations and the current restoration of the painting, it has now been proven that the light gray paint that cocleaed the Cupid was not applied by Vermeer himself but was executed by a different hand decades after the canvas left his studio. It has not yet been possible to identify the originator of this overpainting that completely covered the background picture, including its broad black frame, nor to determine at what point in time it was performed. Uta Neidhardt, the Gemäldegalerie’s senior conservator, said at the time of the reveal Cupid was "the most sensational experience of [her] career. It makes it a different painting."

The Cupid would have made it clear that the content of the young woman's letter was of an amorous nature. The vanishing point of the painting's perspective would have been in the center of the lower part of the painting of Cupid making it a crucial pictorial element in the painting.

From what we can tell from the version of the Cupid in A Lady Standing at a Virginal, Cupid was most likely a work of Cesar van Everdingen, a painter who today is virtually unknown to the general public. In common with so many forgotten or underestimated artists, Van Everdingen occupied an important place in the art of his own time. The century-long refusal of critics and connoisseurs to look at his type of art shows signs of coming to an end.

It could not have escaped a young, ambitious painter like Vermeer that Van Everdingen was a superb technician, not only with detail, but with his ability to paint portraits, mythological and allegorical pictures in a broad, yet crisp and polished style. His outstanding strength was his ability to simplify complicated forms to the utmost and convey their underlying essence. In his later years, Vermeer pursued a more classicist agenda where Van Everdingen's painting was more relevant than just being a convenient prop.

Recently, Uta Neidhart, the curator of Dutch and Flemish paintings at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister where Vermeer's painting is housed, has suggested another author of the Cupid: Jacob Van Loo. Van Loo was a successful painter in Amsterdam who is thought to have inspired Vermeer's early Diana and her Companions with a work of the same subject. Neither points out a putto figure on the far left of Van Loo's Allegorical Figure of a Dead Child with Three Putti who has "short wings, a round face and curly, helmet-style haircut, with a gaze directed at the viewer," showing a strong resemblance to the Cupid in Vermeer's Girl Reading Letter at an Open Window.

It is also know that Van Loo painted a Cupid as well. Neidhart also relates that the work of Van Loo was purchased by Delft art collectors, including the Delft innkeeper Cornelis Cornelisz. De Helt and Magdalena van Ruijven, who famously inherited 20 works by Vermeer from her parents.

The red curtain

The Death of the Virgin

Caravaggio

1604–1606

Oil on canvas, 369 x 245 cm.

Louvre, Paris

One critic has asserted that Vermeer's crimson curtain with its sinuous folding would be very hard to find outside the paintings of Caravaggio (see the detail left of Caravaggio's Death of Saint Anna).

The dramatic lighting, crude subject matter and bold arrangements of Caravaggio's paintings had a profound impact on many European painters. The Italian artist's influence was also felt in the Netherlands and in particular by the school of Utrecht with whom Vermeer seems initially to have shared some interests. Vermeer's mother-in-law, Maria Thins, had family ties with one of the key figures in Utrecht, Abraham Bloemaert. Thins possessed a discreet collection of paintings by Utrecht artists three of which appear on the background wall of Vermeer's paintings, including the standing Cupid in the present work.

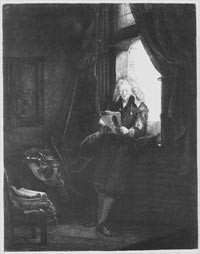

Rembrandt's influence?

Portrait of Jan Six

Rembrandt van Rijn

1647

Etching, drypoint and burin, 24.4 x 19 cm.

In the present painting and the following Officer with a Laughing Girl, Vermeer began to experiment with what was to become the primary compositional concern of his career: that of placing a figure or figures in a coherent three-dimensional space filled with natural light.

Although the theme of solitary figures reading and writing letters had become common subject matter, it was Rembrandt who was responsible for the most distinguished treatment of the subject (see left etching Portrait of Jan Six). Vermeer's Girl Reading Letter at an Open Window has been historically associated with the work of the elder Rembrandt. Even though there exist no documented ties between the two artists, Rembrandt's prints circulated throughout the Netherlands and were prized even by Italian art collectors. In any case, Vermeer had various well-heeled acquaintances in the fine arts, including his patron Pieter van Ruijven, who possessed works of Rembrandt and would have been all too eager to let them be studied by such a promising young artist as Vermeer.

Changes

During the painting process, Vermeer made many significant changes to clarify the works's composition and meaning. X-ray images show that the head of the young girl was turned slightly away from the viewer originally positioned slightly in front and below its present place. The original position accounts for the comparatively full-faced reflection we now see in the window.

The inclusion of a mirrored image in Vermeer's composition may have had also been a sort of reflection on the art of paintings itself. The influential artist and Dutch art writer Samuel van Hoogstraten defined painting as a "mirror of nature." However, Van Hoogstraten was not in favor of blindly describing the natural appearances of things in order to fool the eye but accomplish it in a "pleasurable, permissible and praiseworthy fashion" that might make the deceit acceptable.

Vermeer's wife?

Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (detail)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 46.5 x 39 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The profile of this young girl resembles that of the woman who poses in the Woman in Blue Reading a Letter. Some critics have been sympathetic to seeing the image of Vermeer's wife, Catharina Bolnes, although there exists no objective evidence in merit. Catharina and Vermeer had 15 children in all, 11 of whom survived the early years of childhood.

In any case, if the affection with which the young girl is painted was directed towards Vermeer's wife, it would not have been unusual at the time. While in the rest of Europe, obedience was largely considered the fulcrum of matrimony, in the Netherlands things were different. Humanists had long held that tenderhearted sentiment and love were at the core of the marriage bond. Love was not subordinated to marriage but rather exalted it as the indispensable quality for a godly union.

Foreign visitors to the Netherlands were often surprised and embarrassed to witness the outward signs of friendship of married couples. The Frenchman De la Barre de Beaumarchais dined with a burgomaster of Alkmaar who went so far as to compliment his wife on the meal, to which she responded with a kiss.

Public demonstration of affection was not limited to married couples. Public kissing, candid speech, unaccompanied promenades struck foreign men, and especially the French, as shockingly improper even though they were repeatedly assured of the impregnable chastity of the married woman.

A satin jacket

The Music Lesson (detail)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 64.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

This smart satin yellow jacket was later worn by the young woman who is playing music in The Music Lesson. Women wear the same bodice in four other early paintings: Officer and Laughing Girl, The Concert and Young Woman Holding a Water Pitcher. Although used for daily wear, this trim garment must have lent Vermeer's paintings a voguish contemporary look, an effect which was sought after by the upper tier of Dutch interior painters in the 1650s and 1660s. In the Netherlands, it was sometimes called a schort or a wacht although it has been erroneously referred to in Vermeer literature as a caraco or a pet en l'air (both terms refer to a later and somewhat different type of garment).

It is curious to note that in The Music Lesson and the present composition the girls' faces are seen in nearby reflections.

The jacket is painted with extraordinary vigor. The high relief paint (impasto) of the illuminated portion of the garment attracts the viewer's eye and makes it sparkle with life. The famous pointillés, or spherical dabs of thick opaque paint, make their first appearance in Vermeer's work in this canvas. Many critics believe that they suggest the use of the camera obscura, a kind of primitive photographic camera that was known and, perhaps, used by a few Dutch painters other than Vermeer.

The "Spanish chair"

The so-called Spanish chairs, which appear in various versions in Vermeer's compositions, are found in a great number of genre interior paintings of the time. Two such chairs can be seen in Pieter de Hooch's The Bedroom. An identical one, with a lozenge motif, will be represented in Vermeer's Officer and Laughing Girl painted a few years after the present work. Very few of these actual chairs have survived. Some are still housed in the Prinsenhof Museum in Delft and the Rijksmuseum.

Recent investigations have revealed the lion-head finials of a second Spanish chair that was positioned in front of the carpet-covered table facing the viewer. The stippled brown paint and the first highlights of the finials suggest it was brought to a reasonable state of finish before it was overpainted by the carpet.

Being made of walnut, the typical Spanish chair was much lighter than the average sixteenth-century chair but adequately strong. The turned baluster legs were connected by straight stretchers at three places located one above the other. The seat's upholstery and back were made of thick leather fastened with decorative brass nails. Lion masks, sometimes with rings hanging from their mouths, perched at the top of the back posts. After a great deal of conflict among the various woodworkers' guilds, the new guild of the Spanish chair-makers came into existence.

A "Turkish" carpet

Constantijn Huygens and his Clerk

Thomas de Keyser

1627

92.4 x 69.3 cm.

National Gallery, London

The so-called "Turkish" carpets. (the term "Turkish" was used for anything that was imported from the Middle East) can be seen in an extraordinary number of Dutch genre paintings of the time. These carpets were one of the many exotic imports which appealed to the 17th-century Dutch. However, in depictions of the time, they rarely appear placed on the floor, most probably because they were considered too precious to be soiled. It must have been their colorful patterns and plush texture that provided an opportunity to show off the artists' mimetic abilities and create more luxurious environments which would appeal to upper-class purchasers.

In Vermeer's times, practical, wooden-planked floors were generally employed for household use, sometimes covered with woven reed mats to shield the inhabitants' feet from the gelid Dutch winter. Thus, paintings with carpets demonstrate that the artists' renderings of domestic interiors rested somewhere between artifice and reality.

Perhaps a more faithful example of how upper-class houses were actually furnished can be seen in the portrait of Constantijn Huygens, a Dutch diplomat of the court in The Hague and one of the one most influential art connoisseurs of the time. De Keyser portrays Huygens sitting at his desk in his house in The Hague, attended by a servant carrying a written message. Behind Huygens hangs a rich, ornate tapestry with his coat of arms. Above the mantelpiece is a marine painting in the style of Jan Porcellis, whom Huygens admired. On the table is a long-necked lute or chitarrone, and a pair of globes all expensive objects. We clearly see that in Huygens' luxurious dwelling the carpet was placed on the top of the table as in Vermeer's painting while the flooring, notwithstanding Huygens' substantial economic position, is made of wide, unadorned planks of wood.

The still life

Still Life with Fruit in a Wan-Li Bowl

and a Roemer

Gillis Gillisz. de Berg

1637–1639

57 x 68 cm.

Gemeente Musea, Delft

Vermeer often drew inspiration for his themes and compositions from other painters, including various artists from his hometown, Delft. It is tempting to believe that before he painted the Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window he had seen this still life by Gillis Gillisz de Bergh, Still Life with Fruit in a Wan-Li Bowl and a Roemer painted in the late 1630s. The decorative patters of the bowl were painted with precious natural ultramarine, the most costly pigment of the time, imported from Afghanistan through Venice. The recent removal of the painting's old varnish brought to light a small violet glint on the shadowed underside of the bowl, which should be read as a reflection of the carpet.

Curiously, if De Bergh's composition is inverted left to right, it is similar to Vermeer's still life. A large Roemer glass similar to the one in De Bergh's work was a part of Vermeer's original composition on the far right-hand side of the table. It was later painted out in favor of the green trompe l'œil curtain.

In total, the still life in Vermeer's painting features twelve pieces of fruit, including peaches, plums, oranges and two large apples. Some were not part of the original composition but added at a later stage. The artist had no lack of models to chose from, as numerous expert still-life painters were working in Delft when Vermeer was active. Each fruit is modeled with a slightly different technique that would most effectively represent the texture of each.

A similar still life with fruit in a ceramic bowl appears in Vermeer's earliest single-figured interior painting, A Maid Asleep.

The letter

Quodlibet

Cornelis Norbertus Gysbrechts

1665

Oil on canvas, 41 x 34.5 cm.

Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne

In Dutch painting, women who read letters are almost always associated with love, and artists found various means to portray both the air of expectation at the arrival of a letter and their subsequent reaction to it. During Vermeer's lifetime, letter-writing was a sign of cultivation. Letter-writing manuals were popular books and contained instructions on calligraphy and how to achieve the right tone.

Letters were usually not inserted in envelopes but folded in three and sealed with wax because paper was still quite expensive. Period paintings (see trompe the l'œil still lifes by Cornelis Gysbrechts, left) usually show that letters were folded and either sealed with wax or tied up with a cord. When a lady was in a hurry, she might use a ribbon of her headdress or garment, sometimes wrapped in a small piece of fine cloth. Since mass-produced envelopes weren’t invented until the 1830s, most 17th-century letter writers folded their correspondence in such a way that it became its own envelope—a process Jan Dambrogio, a researcher in letter security, has recently dubbed "letterlocking." Letterlocking was also a necessity due to the high cost of paper. Letterlocks could be simple, just a series of quick folds without any sort of adhesive, or incredibly complex, even booby-trapped to reveal evidence of tampering.

The journalist Richard Fisher wrote that in order to prevent her captors from snooping into her correspondence, the imprisoned Mary Queen of Scots devised an ingenious letter-locking system. "She cut a thin strip from the paper margin, before folding up her message into a small rectangle. After poking the knife through the rectangle to make a hole, she then fed the strip through, looping it and tightening it a few times, creating a 'spiral lock.' No wax or adhesive was required, but crucially, if someone tried to sneak a look, they would have to rip through the strip, so her brother-in-law would know the message had been intercepted. "

The skirt

The Music Lesson(detail)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1664

Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 64.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

This dark gray skirt appears only one time in Vermeer's oeuvre, except, perhaps, in The Music Lesson where it is worn with the same smart yellow stain bodice and drawn up to expose a red petticoat. A decorative strip of black fabric runs down the very front side suggesting that it is not ordinary houseware, but something more stylish. The outward flare creates a simple bell-like form which was much in vogue in the years Vermeer painted this picture. The fabric was probably too loose to create this shape and was gotten by wearing one or more layers of petticoats underneath, as was common. In The Music Lesson, the skirt appears to be sewn onto the bodice.

White-washed wall

Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, Johannes Vermeer(detail)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1657–1659

Oil on canvas, 83 x 64.5 cm.

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

The first step in the recent restoration of the Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window was to remove the old varnish, which had turned yellow-brown through aging. The varnish dates from the 19th century and was "revived" several times since then. The removal of the varnish revealed Vermeer's rich palette, which has little to do with the former Old Master tone, in line with other early works such as The Procuress, The Milkmaid and Officer and Laughing Girl. The cool light gray of the background wall (see detail image) evokes the airy early morning light flowing through the open window. The restoration also showed that the picture—apart from the edges of the picture—was in an excellent state of conservation.

special topics

- A Cupid Revealed: The Spectacular Results of the recent Restoration!

- Painting for a Competitive Art Market

- The Dutch Household

- Did Vermeer's Interiors ever Exist?

- Is the Young >Girl Vermeer's Wife?

- The Limits of Vermeer's Fame

- Imported Chinese Porcelain

- Fruit in Painting

- Abandoning his Master's Teachings

- The Lost Roemer Drinking Glass

- Listen to Period Music

fact sheet

- Signature

- Date

- Provenance

- Exhibitions

- Technical Description

- Before and After Images of the Painting's Restoration

- The Painting with its Frame

- How Big is this Picture?

- Historic Timeline of the Year(s) Vermeer Created this Painting

- Related Artworks

The signature

signed lower right (to the right of the woman's skirt): J Meer [fragmentary]

(Click here to access a complete study of Vermeer's signatures.)

Dates

1659

Albert Blankert, Vermeer: 1632–1675, 1975

c.1657

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer, London, 1997

c.1657

Walter Liedtke, Vermeer: The Complete Paintings, New York, 2008

c. 1657–1658

Wayne Franits, Vermeer, 2015

(Click here to access a complete study of the dates of Vermeer's paintings).

Technical report

The support is a plain weave linen with a thread count of 12–16 threads per cm². The variation in the number of threads is caused by the slight difference of the threads' denier between 0,2 and 1 mm.

An x-ray photograph shows considerable fabric strain up to 1 cm. in each dimension, reaching up to 15 cm. towards the middle of the picture. The strain had been fixed by the grounding of the support. This unusually strong straining may indicate that the support was not prepared by a professional witter.

Although the support no longer has its original tacking edges, the entire fabric used for the painting has been preserved. The painting's 83 x 64.5 cm. (height to width ratio: 1,28:1) format was rarely used by Vermeer.

The white ground is a mixture of lead white and chalk (lootwit), bound only with protein and applied in a relatively thick layer of 0.15 mm.

Only a few traces of underdrawing and underpainting (mainly in a light reddish-brown or light grey) are possible to detect, implying in their execution the ground layer's grade of lightness. The most distinctive area of underpainting is visible in the upper part of the window's inner embrasure, to the left of the red curtain. The underpainting of the carpet initially excluded the bowl with fruit. The row of the pattern in that area didn't leave out the objects' outlines.

The perspectival construction was probably drawn from direct observation without any mechanical aid. This likely explains why the vanishing lines of the window frame do not meet exactly in the vanishing point beyond the girl's head in the right half of the picture.

The colors used for the painting were already determined by Kühn (1968, 181–82). Apart from the lead white, for the shadowed parts mixed with umber and traces of charcoal, Vermeer employed lead-tin yellow for the girl's bodice and sleeves as well as for a great part of the highlights (including those for the brass nails at the back of the chair). The red paints for the curtain and the tablecloth are vermilion and madder lake, mixed with lead white in the light passages. The green of the trompe l'oeil curtain is created by a mixture of azurite and lead-tin yellow. Ultramarine appears (in admixtures with lead white) for the first time in the window frame and in the tablecloth. A curiosity has been detected during the recent analysis, in the girl's hairdo, created with fine dots of light and dark brown, various tones of ochre and some reddish nuances Vermeer set two light blue dabs in the sort of hair-band running vertically around the coiffure, perhaps an early allusion to his later so preferred contrast of yellow and blue.

Rather than sharp edges, Vermeer extends his technique of blurring the contours with dabs and dots to enhance the effects of depth and surface texture. These dots again serve as a special reflective background for the highlights glazed in light colors where the natural light encounters the objects' textures.

It has not been possible to fix with certainty the chronological sequence of the alterations made during the painting process. The window (the first one in Vermeer's early oeuvre), the chair in the left-side corner and the left side of the carpet with the still life clearly demonstrate Vermeer's purposeful painting method and were not affected by extensive reworking.

The mirroring of the girl's face in the window points to a variation in the girl's initial posture, with her back turned towards the viewer (a probable allusion to Ter Borch's young satin-dressed ladies depicted in rear view). After Vermeer had changed her posture to assume a full profile he left the reflection in the mirror in its initial stage except for a slight correction in the upper left window pane.

Before Vermeer added the green curtain, which is not part of the depicted scene, he experimented with at least two other repoussoir motives to enhance the illusion of spatial depth. One of them was a large roemer glass decorated with raspberry prunts and surrounded by a tendril of wine leaves. The other was an object previously assumed to be a Venetian winged glass. Recent infrared reflectography shows this rounded form next to the fruit lying right on the table with remarkable clarity and suggests a lion head finial of a second chair in the foreground placed close to the table, serving as an ulterior repoussoir motif. The form of the left-side lion head was once left out in the respective pattern of the tablecloth and was already defined with a precise light edge. In the painting, this part is still visible in the somewhat undefined pattern of the carpet and the slight luminosity next to the fruit lying far right on the table.

The green curtain had already been executed when Vermeer began to overpaint the large painting of the Cupid. The earlier assumption is that Vermeer would have intended to "rescue" the Cupid-painting by leaving an imaginary shadow of its contour cannot be proved. The visible pentimento Cupid-picture and its black frame, in particular, is due to aging and progressive transparency of the paint (resp. admixture) used for the overpainting.

based on: Christoph Schölzel, "Zur Entstehung des Gemäldes Brieflesendes Mädchen am offenen Fenster," in: Der frühe Vermeer, ed. Uta Neidhardt, Berlin, München 2010, 83–97 (exh.-cat. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister).

Provenance

- (?) Pieter van der Lip sale, 14 June, 1712, no. 22;

- April 1742 acquired by the Saxon secretary of embassy, de Brais in Paris for the Elector of Saxony, August III, as by Rembrandt;

- 1945–1955 in the Soviet Union (requisition of war);

- 1955 restituted to Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden (inv. 1336).

Exhibitions

- Tokyo September 20–November 24, 1974

Meisterwerke der Europäischen Kunst

Nationalmuseum for Western Art - Kyoto December 2, 1974–January 26, 1975

Meisterwerke der Europäischen Kunst

Nationalmuseum - Moscow October 10–November 18, 1984

Gerettete Meisterwerke

Puschkin Museum - Leningrad [formerly St. Petrsberg] December 6, 1984–January 20, 1985

Gerettete Meisterwerke

Staatliche Eremitage - Madrid February 19–May 18, 2003

Vermeer y el interior holandés

Il Prado

165–167, no. 32 and ill. - Kobe January–May 22, 2005

Dresden-Spiegel der Welt. Die Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden in Japan

Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art - Tokyo June 28–September 19, 2005

Dresden-Spiegel der Welt. Die Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden in Japan

National Museum of Western Art - Dresden September 3–November 28, 2010

Der frühe Vermeer

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister - Dresden June, 4–September 12, 2021

Vermeer: On Reflection

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden - Tokyo February 10–April 3, 2022

Johannes Vermeer and 17th-Century Dutch Paintings

Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum - Amsterdam February 10– June 4, 2023

VERMEER

Rijksmuseum

no. 6 and ill.

- Sapporo April 22–June 26, 2022

Johannes Vermeer and the Masters of the Golden Age of Dutch Painting from the collection of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

- Osaka July 16-September 25, 2022

Johannes Vermeer and the Masters of the Golden Age of Dutch Painting from the collection of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Osaka Museum of Fine Arts

- Sendai October 8–November 27, 2022

Johannes Vermeer and the Masters of the Golden Age of Dutch Painting from the collection of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

(Click here to access a complete, sortable list of the exhibitions of Vermeer's paintings).

Painting for a competitive art market

Self Portrait in the Studio

Gillis van Tilborgh

c. 1645

Oil on panel, 10.8 x 8.9 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

It has been estimated that about 650 to 750 painters were working in the Netherlands in the 1650s, or about one for each 2,000 to 3,000 inhabitants, in Delft one out of every 500. By comparison, the number of painters in Renaissance Italy was about one every 330, in a population of some 9 million. Most Dutch painters came from middle-class families because painting generally did not offer sufficient status to attract the wealthy and the poor could rarely afford the training. As their status and social ambition rose, some Dutch artists assumed the manners and dress of their wealthy clients. Vermeer himself appears to have made serious efforts to cast himself as a gentleman/artist.

When the young painter turned his attention to the domestic interior motif, he entered into a highly competitive niche market already dominated by a few exceptional artists such as Gerrit ter Borch, Frans van Mieris and Gerrit Dou. These painters specialized in themes of upper-class domestic interiors now grouped, together with a host of other subjects, under the term "genre." Their work displays a truly astonishing level of detail, at times near microscopic, and required enormous number of work hours making them affordable only for a select few. Dou is reported to have sold some works for more than 1,000 guilders or roughly the equivalent of a venerated great Italian Master. A modest Dutch house could be had for less.

The Dutch household

Before the 1650s, few rooms in a typical middle-class Dutch house had specialized functions. Beds, for example, were placed in halls, kitchens or wherever they could fit. But when rooms began to assume a particular use, it was often reflected in the paintings chosen to decorate them—domestic scenes or religious images were selected more often for private areas of the house while landscapes or city views were shown in rooms exposed to the public .

Typical Dutch homes were generally far more cluttered and not as well-lit as the pristine environments that appear in Vermeer's compositions.

Although exceptionally few Dutch domestic environments have survived, a few doll houses made in Amsterdam in the second half of the 17th century are regarded as an inexhaustible source of information about the furnishing of grand merchant's houses in the heyday of the Dutch Republic. One such dollhouse was commissioned by Petronella Oortsman (1656–1718), who as a wealthy widow married the silk merchant Johannes Brandt in 1686. She started assembling her doll's house shortly after marriage.

The Rijksmuseum Amsterdam estimates that Petronella Oortman spent twenty to thirty thousand guilders on her model house, the price of a real house along one of Amsterdam's most sought-after canal locations at the time. It took nearly 20 years to build.

Did Vermeer's interiors ever exist?

Historians of economics have estimated that about five million works of art that were created in the Dutch Republic during the 17th century. Interiors views and still-lives comprised at least 10% of the total output, or about five hundred thousand works. And since these works are so expertly painted, the viewer tends to believe that the artist painted exactly what was in front of him. However, the most outstanding aspect of these images, namely, their apparent capacity to offer unmediated access to the past, is paradoxically the most deceptive. Art historians have concluded that we are dealing with a case of modified reality rather than a literal transcription of Dutch homes. The sitters in their environments that we see were meticulously arranged combining both real and fictive elements.

Merry Company at a Table

Hendrick van der Burch

55 x 69 cm.

Private collection

While the window casements and walls in Vermeer's rooms appear to be factual, the marble floors were fictive. The more humble objects, such as the porcelain wine jugs, tables, pictures, mirrors and maps, were probably Vermeer's own. On the other hand, the luxurious hand-woven tapestries, the keyboard instruments and the gilt chandelier were borrowed and brought in Vermeer's studio for the occasion. Vermeer had full access to these luxury items through his rich Delft patron Pieter van Ruijven or similar channels.

In a certain sense, Vermeer's painted environments are analogous to the photo reproductions of today's interiors design magazines advertising luxury homes, which are assembled only to be photographed and afterward disassembled. They both portray an ideal interior—brighter, cleaner, neater and more richly decorated. Moreover, these pictures were expensive commodities in themselves which would have bolstered the cultural pretension of their owners.

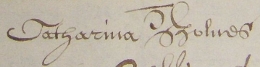

Is the young girl Vermeer's wife?

The signature of Catharina Bolnes on a legal document

Many writers believe that this handsome young woman in the present painting is Vermeer's wife, Catharina Bolnes. As is the case for the vast number of common 17th-century men and women, the voice of Catharina Bolnes has been lost. Not a single letter, diary entry or note by her hand has survived. Only once are we able to pick up her faint voice through a document dated 24th and 30th April, 1676. Catharina, in a desperate attempt to flee the grip of her creditors after the untimely death of her husband, spoke of her Johannes so: "as a result and owing to the great burden of his children, having no means of his own, he had lapsed into such decay and decadence, which he had so taken to heart that, as if he had fallen into a frenzy, in a day or a day and a half had gone from being healthy to being dead." After Johannes' death, Catharina was alone with her mother, saddled with ten minors and full of debt.

Catharina would have remained silent had it not been for the notoriety of her husband for whom historians have combed every shred of documentary evidence that could have possibly regarded the artist, his colleagues and his family. What we know largely emerges from legal testimonies elegantly transcribed on vellum ledger books by Dutch notaries, probably the most meticulous note-takers of all times. The evidence which regards Catharina tells us that we are in front of an exceptional woman, at least in relation to the anonymous 750,000 women of the time who lived in the Netherlands.

The limits of Vermeer's fame

Portrait of Arnold Houbraken (1660–1719)

author of De groote

schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders

en schilderessen (The Great Theatre

of Dutch Painters), in an engraving by his

son Jacob.

The popular myth about Vermeer's fame goes that he was recovered from total obscurity by the French critic Thoré-Bürger in the mid-1800s. Like many myths, this one contains some but not all the truth. Although Vermeer was not well known in his time outside his native town Delft, his works were never completely forgotten.

After the artist's early death, some of his works continued to hold considerable value to several generations of Amsterdam collectors with money and taste, and a few works continued to evoke admiration and high prices whenever they came onto the market. But for unclear reasons, the name of Vermeer was excluded from Arnold Houbraken's Groote Schouburgh, the foundational 18th-century book on Dutch artists. Thus, for almost 150 years after his death, Vermeer's fame hardly spread outside of the Netherlands.

It is a curious fact that the Vermeer canvases which left the Netherlands were not infrequently attributed to familiar Dutch artists known to outsiders. In 1742, for example, his Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window came to Dresden as a Rembrandt.

Imported Chinese porcelain

Interior with a Dordrecht Family (detail)

Nicolaes Maes

1656

112.4 x 121.0 cm.

The Norton Simon Foundation

The type of Chinese porcelain that appears in the present work was imported in huge quantities for European consumption by the East Indies Company, or VOC as it was called by the Dutch. Vermeer and his fellow citizens must have been particularly familiar with objects of this kind because Delft was one of the six towns in Holland that had a chamber of the VOC. As the world's first multinational company, the VOC had commercial interests all over the globe and accessed the world's oceans through Delfshaven, Delft's 17th-century harbor town. With a little imagination, one can picture merchant ships busily unloading their precious cargoes on the quay of Vermeer's View of Delft, connected to Delfshaven by the canal which exits the right-hand part of the composition.

To give an idea of the colossal proportions of the porcelain trade, in 1608, one of the first years of organized trade, the VOC had ordered 50,000 butter dishes, 10,000 plates, 2,000 fruit dishes, and 1,000 salt cellars, mustard pots and various wide bowls and dishes plus an unspecified number of jugs and cups. In a few years, these articles could be found in many Dutch households. In 1640, the ship Nassau carried an astronomical number of pieces, 126,391 in all, to Amsterdam. The trade with China continued unabated until the mid-17th century when civil wars caused by the fall of the Ming dynasty (1644) disrupted suppliers, after which European traders turned to Japan.

Fine porcelain would have normally been displayed on the household's best cabinets or on specially-made racks. Nonetheless, these rare objects had no cultural value for the Dutch outside the fact that they were exotic, precious and expensive regardless of their style or even their quality. Thus for Vermeer, the exotic motifs which decorated them had no symbolic meaning, and so, they must be taken literally as rare objects, beautiful in themselves.

Chinese potters had produced porcelain for export markets all over the world. Ironically, what the Dutch considered the epitome of style was second-rate porcelain for the Chinese. The special models made for export rarely attracted Chinese taste. Many of these "unpalatable" hybrids appear in Dutch still life paintings, and were taken as the epitome of refinery. Instead, products destined for Chinese domestic consumption were made according to higher standards of taste and facture. Period documents reveal that the finest exemplars were not allowed out of the country on penalty of corporal punishments.

The Dutch had no regard for porcelain's original use, and as years passed, it eventually found its way onto the dinner table because it was incredibly easy to clean and did not pass on the food's flavor to the next meal.

Even though the Dutch were poor judges of Chinese standards, they knew that they surpassed anything produced in Europe.

Fruit in painting

Woman with a Basket of Fruit

Christiaen van Couwenbergh

1642

107.5 x 93 cm.

Gemäldesammlung der Universität, Göttingen

In Vermeer's time, there existed a long tradition of paintings of women with luscious fruit. Symbolically, fruit could alternately allude to the figure of Venus (the goddess of love) in the Judgment of Paris or the Biblical apple (the symbol of sin) of Adam and Eve. The appearance of fruit in European easel painting exceeds any other kinds of food although very rarely do we see the fruit actually being eaten. Fruit's popularity as a motif in painting is owed to its visual appeal, brilliant colors, shapes and variety of peculiar textures, making it a particularly stimulating challenge. Moreover, fruit generally has positive associations owing to its sweetness. From the 16th century on, artists created numerous portraits of beautiful women accessorized with fruit or holding bowls or attractive baskets of it. Bowls and baskets of fruit were common features in busts of the figure of the "temptress," particularly in the works of Dutch painters such as Gerrit van Honthorst and Christiaan van Couwenbergh.

In the Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, Vermeer displays in great evidence an imported Chinese Wan-Li bowl with peaches, plums and two large apple. One peach has been halved with its rounded pit exposed to the viewer. The exhibition of ripe fruit alludes, perhaps, to the fullness of the letter reader, perhaps, opened, or "ripe," for love. A Dutch poet once recommended to "send apples, send pears or other fruit" to win over the heart of one's lover drawing inspiration from Ovid's Ars Amatoria.

Abandoning his master's teachings

Four years after Vermeer was accepted into the St Luke Guild in Delft, he painted the present work and established his definitive artistic direction. No evidence explains what might have induced him to reject his initial classical teachings—his master remains unknown—and foray into the genre painting mode. But so divergent was his new approach that had they not been signed, it is doubtful that scholars would have ever attributed the early Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, Diana and her Companions or even The Procuress to Vermeer.

In the 17th-century Netherlands, independence from one's master was not unusual. Some painters were satisfied to preserve the artistic tradition of their masters while many broke away to explore new themes and styles. No few painters worked successfully in different styles. Samuel Van Hoogstraten, an important painter and art theoretician of the time, painted simultaneously in the "antique" mode, producing large-scale history paintings of biblical and classical themes, small trompe-l'œil paintings and a few genre scenes of contemporary life clearly anchored in the "modern" mode. Interior painters occasionally tried their hand at still life. Some portrait painters, who worked in one of the most highly specialized fields, dabbled in the distant landscape genre. In the Netherlands, the amazing variety of available themes and techniques had been stimulated by an open and variegated art market and the absence of official academies.

The only requirements for changing modes of painting was sufficient talent and a knack for understanding what might appeal to a given clientele.

Listen to period music

![]() Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach

Suite française no. 1, Sarabande [1.79 MB]

Gustav Leonhardt, harpsichord

http://www.bach-cantatas.com/Bio/Leonhardt-Gustav.htm

A Cupid revealed: the spectacular results of an ongoing restoration!

text and image drawn from the Dresden Gemäldegalerie website:

In the spring of 2017, a comprehensive restoration of Vermeer's Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window was initiated by the conservator of the Christoph Schölzel. The first stage in the restoration process was the removal of old layers of varnish which had turned yellowish-brown as a result of aging. This coating had been applied in the 19th century and had been subsequently "revived" several times. The removal of the varnish revealed subtle, cool colors of Vermeer's original painting. It also became evident that the painting was — apart from the edge areas — in an excellent state of preservation, given that it is 360 years old.

An x-ray photograph taken decades ago revealed that behind the solitary female figure the artist had originally incorporated a large ebony-framed "painting-within-a-painting" of a pot-bellied Cupid. It was believed that the artist himself, unsatisfied with the results, presumably painted out the picture to nuance its iconographic significance and/or improve the compositional equilibrium. However, investigations concerning the structure of the paint layers showed that aged layers of binding agent and a layer of dirt were sanwiched between the original paint applied by Vermeer and the paint used for overpainting the Cupid picture. Therefore, a period of several decades must have intervened between the completion of the painting with the Cupid picture and the application of the layer of overpainting, which means that Vermeer cannot have painted over the background picture himself. When the painting came to Dresden from the collection of the Prince of Carignan in France in 1742, this major change to the composition had evidently already been carried out.

Following numerous tests, it was determined that the best method for removing the layer of overpainting was to use a fine scalpel under a microscope. Only in this way is it possible to retain the layers of binding agent between the original paint layer and the paint used for the overpainting. The later overpainting of the Cupid was undoubtedly due to altered tastes and not to any damage to the paint layer.

Although only about half of the Cupid picture on the rear wall of the room has so far been exposed, the fundamental change to the overall impression of the painting is already evident. It is now clear that the Dresden Girl Reading a Letter is another one of the numerous interior scenes by Vermeer in which there is a painting-within-a-painting located on the rear wall. In this case, the artist was probably quoting a painting in which a standing Cupid was depicted with an upright bow in his right hand and with his left arm raised. This motif is already known from three other interior paintings by Vermeer. After completing the restoration of Vermeer's Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, the painting is again on display.

The lost roemer drinking glass

An x-ray image of 1979 shows that before it was painted out by the artist, Vermeer had inserted a rather large drinking glass, called a roemer, painted in shades of dark-blue gray, near the right-hand corner of the picture. X-ray images allow us to calculate that the glass was bout 18 centimetres high, more than half the size of the figure of the girl. The roemer is fancy drinking glasses with a capacious cup a small foot and a hollow stem, often studded with raspberry prunts. The roemer in Vermeer's painting must have been brought to an advanced state of finish since it is possible to make out the highlights of the prunts, a trailing vine tendril and the level of wine in the glass. It was covered by the green curtain. A similar composition arrangement with a roemer can be noted in seen in a drawing by Leonaert Bramers (1596–1674), a highly respected Delft painter who was in personal contact with Vermeer’s family.

Curiously, the foot of the roemer did not rest on the table but at the very bottom edge of the painting, on what may have been intended to be a marbleized ledge. However, the conservator Christoph Schölzel, who restored the painting, suggests that it is not currently not possible to determine if the roemer was an integral part of the composition, or a remnant of and earlier composition, due to its rather unlikely position along the very bottom edge of the canvas.