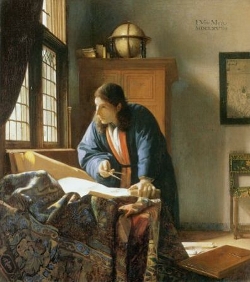

The Geographer

(De geograaf)c. 1668–1669

Oil on canvas 53 x 46.6 cm. (20 7/8 x 18 1/4 in.)

Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

inv. 1149

The textual material contained in the Essential Vermeer Interactive Catalogue would fill a hefty-sized book, and is enhanced by more than 1,000 corollary images. In order to use the catalogue most advantageously:

1. Slowly scroll your mouse over the painting to a point of particular interest. Relative information and images will slide into the box located to the right of the painting. To hold and scroll the slide-in information, single click on area of interest. To release the slide-in information, single-click on the painting again and continue exploring.

2. To access Special Topics and Fact Sheet information and accessory images, single-click any list item. To release slide-in information, click on any list item and continue exploring.

The terrestrial globe

The 17th century was a time of profound discovery, marked not only by the ambitions of adventurers and traders but also by those of geographers and astronomers.

As James Welu highlighted, Hendrick Hondius' terrestrial globe, positioned on a cabinet with a four-legged stand, prominently displays the Indian Ocean. This might serve as a nod to national pride, as this was the route Dutch traders used to reach China and Japan.

The text of the decorative cartouche on the lower right-hand side of the globe (which is illegible in Vermeer's painting) reads in part: "Since very frequent expeditions are started every day to all parts of the world, by which their positions are clearly seen and reported, I trust that it will not appear strange to anyone if this description of the globe differs very much from others previously published by us...we ask the benevolent leader, that if he should have a more complete knowledge of some place, he willingly, communicate the same to us for the sake of increasing the public good." This same terrestrial globe makes another appearance in Vermeer's subsequent Allegory of Faith, albeit with a contrasting allegorical significance.

Dutch mapmaking in the 16th and 17th centuries stood out for its intricate decorative features. Notably, the cartes à figures were renowned for their ornate panels that showcased figures, landscapes and various possessions. Family businesses produced the majority of the maps and atlases from this era.

The Golden Age of Dutch cartography, often termed the "Golden Age of Mapmaking," corresponded with the Netherlands' ascent as a prominent global naval power. Printed maps not only served as essential navigation tools but also as indicators of Dutch achievements in exploration, trade and science. The close collaboration between cartographers, artists and engravers resulted in maps that were both functional and aesthetically captivating. It's worth noting that maps from this period were not merely tools but were also viewed as works of art, often displayed in the homes of the affluent as a symbol of wealth and worldliness.

The black-framed nautical chart

Vermeer adorned his scholar with objects fitting for his study. The black-framed decorative nautical chart of "all the Sea coasts of Europe" was crafted by Willem Jansz Blaeu in 1600, who managed one of the largest publishing houses in Amsterdam. The displayed globe, featuring the Indian Ocean and the sea chart of Europe, bears the inscriptions "Orientalis Oceanus and Oceanus Occidentalis", which are the routes that the ships of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) utilized for their expansive trade overseas.

The detail to the left is derived from a surviving copy of the background map, spotlighting the region that appears in Vermeer's artwork. Within this sea chart, one can discern the Iberian and Italian peninsulas as well as a segment of Northern Africa, oriented with the South on the left and the North on the right. Map orientation had yet to be standardized during that era. Sea charts customarily offered limited details of the adjacent land, concentrating instead on navigational landmarks and dangers, anchor points and soundings. These maps often featured illustrations of ships with billowing sails and fabled sea creatures as ornamental additions.

Considering the presence of the decorative cartouches, this map might have been designed for both framing and practical application. An example of such a map resides in the Deutsche Staatsbibliotek in Berlin.

The sea chart might suggest the necessity to navigate one's path in the world and, metaphorically, through life. Maps and charts were highly esteemed in the Dutch mercantile republic, a nation whose prosperity was largely anchored in navigation. Paintings depicting daily life from that period frequently contain portrayals of maps, and Vermeer himself incorporated them on several occasions in his creations.

The floral tapestry

The expansive drapery that spills over the front of the table is so coarsely painted that it appears either unfinished or poorly conserved. Its provenance is uncertain, but the tight, swirling floral pattern suggests it's not what we typically term an oriental carpet—pile-woven carpets imported into Europe in significant quantities from the Islamic world—but rather a tapestry. Its design bears a resemblance to the tapestry in The Astronomer, the likely counterpart of The Geographer.

Historically, carpets and tapestries were depicted with scarcely a crease, consistently flat, either parallel or perpendicular to the picture's plane. Such representations ensured that the captivating patterns and hues, which made these items so sought after, were prominently displayed. Carol Bier, a historian of Islamic art, posited that the geometric patterns of oriental carpets might have catalyzed the evolution of linear perspective. Nonetheless, in the pursuit of heightened naturalistic renderings and to demonstrate their adeptness, Dutch interior painters deviated from convention, choosing to depict ornately decorated carpets crumpled loosely on tables or hanging from ceilings, gathered to the side. Capturing the consistent hue of the detailed, multicolored surfaces across both the illuminated and shadowed portions of these folds was undoubtedly a formidable. task even for the most skilled artist.

Vermeer displayed a marked fascination with the dynamics of flowing drapery—both plain and adorned—and incorporated it into numerous interior scenes. In several of his mid-career pieces, a blue fabric is draped over a foreground table, gathered in pronounced bunches to the side. In The Geographer, the tapestry flows from the tabletop, providing a sort of protective boundary for the figure's workspace and obscuring what might otherwise be a vast and monotonous space beneath the table's surface. The raised folds and pronounced depressions craft a miniature landscape, its high points bathed in the glow of the morning sun. The intricate pattern might symbolize the geographer's cognitive processes.

Inspired by Rembrandt?

Upon close examination of the original painting, one can discern a subtle pentimento to the left of the geographer's forehead. This hints that Vermeer might have initially depicted the forehead at a different angle, perhaps with the figure looking down at the chart on the table.

Faust in his Study

Rembrandt van Rijn

Etching, drypoint and burin on eastern paper, 20.8 x 16 cm.

1650–1662

The posture of Vermeer's geographer mirrors, albeit in reverse, the figure in Rembrandt's renowned Faust, an observation that goes back to Thore-Burger. This could suggest that Rembrandt's piece served as an inspiration for Vermeer. While the moment the scholar gazes out of the window in deep thought is exquisitely captured, the nature of his contemplations—both the questions he poses and the answers he seeks—remains enigmatic.

The Geographer and its likely pendant The Astronomer were Vermeer's only two paintings—at least the only two to survive—with solitary male figures as their protagonists even though their titles have varied in the past. In 1713 they were auctioned as "A work depicting a Mathematical Artist, by Vander Meer" and "A ditto by the same." When they came up for sale again a few years later they were described as "An Astrologer" and 'A repeat" - i.e. another one of the same profession - and were referred to as "extra choice." Later still, The Geographer, as he is now called was re-identified as "an Architect" or "a Surveyor." The description in the catalog for the auction of Jacob Crammer Simonsz.'s collection in Amsterdam referred to the figure as a "Philosopher" and the map in front of him as a "Land map."

Vermeer versus the fijnschilder style of painting

Woman at a Clavichord (detail)

Gerrit Dou

c. 1665

Oil on panel, 37.7 x 29.8 cm.

Dulwich Picture Gallery, Dulwich

Nowhere is the distinction between Vermeer's artistic vision and that of his direct competitors, the fijnschilderen, more evident than in this painting. The dominant masses of color and tone are executed with a boldness and simplicity few of his peers either sought or attained.

The once-renowned but now overlooked Leiden-based school dedicated meticulous care to their artwork, achieving unparalleled illusionistic effects. Their paintings' microscopic detail remains remarkable even today. Gerrit Dou, who arguably took the fijnschilder approach to its zenith, painted each knot of his repoussoir curtains individually. Yet, what's even more astonishing is the painting's overall size: a mere 37 by 30 centimeters. Thus, the detail to the left is only a minor part of Dou's composition. In contrast, Vermeer's curtain is delineated purely by its uncomplicated outline.

A repoussoir, be it a person or an object, is typically positioned in the periphery of the foreground. Often cast in shadow, it doesn't draw excessive attention. Positioned at the edge, it implies the viewer's stance outside the painting's space. Conversely, the brighter central scene appears receded. Hence, the repoussoir serves as a structural tool to amplify spatial depth.

Usually, repoussoir motifs were placed on the composition's left side. This might be because Western observation is influenced by reading direction. Research suggests our eyes tend to scan images from left to right, akin to reading. As such, Vermeer's repoussoir is positioned for the reading gaze which, after a brief pause at the repoussoir, swiftly moves to the painting's focal point—here, the geographer's fleeting gesture, before exploring the remaining artwork. Vermeer employed this repoussoir curtain even more dramatically in The Art of Painting and Allegory of Faith.

The rolled-up chart on the table

Art historian and map specialist James Welu posits that the large translucent rolled chart on the table, distinguished by a few faint lines, could be a nautical chart made of parchment or paper. Unfortunately, past restorations might have compromised the details and visual subtleties in this region. Nonetheless, some experts hypothesize that the painting might have remained incomplete. Alternatively, since the sheet in front of him is blank, one critic suggested Vermeer may have wished to emphasize more the "philosophical character of the process." In this context, the brightly lit area symbolizes a "new beginning" as an "energy field," representing both a "purification" of the depicted person and a "new definition of science."

A revealing pentimento

The presence of a slightly lighter area of paint with curved outlines reveals that Vermeer had eliminated a sheet of paper that once laid on this stool to darken the corner of the composition and guide the viewer's eye towards the center of the composition. As a bright reflection, it would not only have competed with the parchment rolls lying on the floor to the left behind it but would also have interrupted the dense shadow zone in the foreground, emphasizing the barrier-like effect of the repoussoir motifs.

The geographer's dividers

The alterations made to the geographer's figure are particularly revealing. Initially, he held his head slightly elevated and seemingly turned further to the left. Subsequently, his gaze was redirected more downward than in its final depiction. The compass, too, that served the geographer to make precise measurements on his maps, was first aimed in the same direction, suggesting a portrayal of the geographer in the act of applying his thoughts—a more dynamic pose. However, the final version captures a less defined moment of action. The compass, pointing sideways—whose alignment seconds the angles of the yellowish scroll—and the incoming light along with his face turned toward the window and subtly parted lips, accentuates a contemplative and deeply introspective pause. Through the synthesis of composition and illumination, Vermeer masterfully illustrated profound intellectual engagement.

The window

The basic structure of the window seems to be the same as the one in The Astronomer, considered by many critics to be a pendant of The Geographer. However, minor differences in color in each of the window's panes are described more accurately in The Geographer while in The Astronomer a portion of what is most likely red and yellow colored coat of arms can be partially observed. Parts of the window casement appear rather sketchily painted.

Instead of a single, large piece of glass, 17th-century Dutch windows were usually made up of smaller rectangular or square panes, set into a grid of wooden muntins. This was both a practical and aesthetic choice. Given the limitations of glassmaking technology at the time, creating large panes of clear, flat glass was challenging and expensive. Thus, multi-pane windows were more common.

Small panes of glass were often held together by lead strips, known as cames. This type of window is commonly referred to as a "leaded window." The glass pieces would be set into the cames, which were then soldered at the joints to hold them together. This method was particularly useful for creating complex designs or for using different types of glass within one window.

Windows often had exterior shutters made of wood that could be swung closed for protection. Additionally, some windows, particularly those at the ground level, had protective ironwork grilles to deter potential burglars or vandals.

To enhance the transparency of the glass and make it clearer, it was common practice to rub the panes with a mixture of oil and soap. This would fill in any small imperfections in the glass, resulting in a smoother and clearer appearance.

The double signatures

Oddly, there are two signatures on The Geographer. Scholars once believed that the noticeable signature on the background wall (with the date in Roman numerals) was not original even though the date, MDCLXVIIII (1669) was compatible with the date Vermeer experts have ascribed to the painting. On the contrary, the recent restoration of the painting has demonstrated that both signatures are original.

The signature "I.Ver-Meer" and the date "MDCLXVIIII" below it (Fig. 526) are applied in dark gray color in the background in the top right corner of the picture. They were covered with a blue glaze, which was dissolved during cleaning and partially washed into the original craquelure. Letters filled and partially retouched. On some letters, there is a gray shadow tone on the side, which perhaps was intended to create a three-dimensional effect and the impression of an engraved inscription. Another filled signature is located in the cabinet on the right door: "Meer.," (Fig. 527). It is in light blue, and a darker gray-blue was applied over it. The craquelure, which partially closed like the other signature, is due to cleaning, especially affecting the first letter. However, both signatures are original and well integrated into the paint layer.The signature "I.Ver-Meer" and the date"MDCLXVIIII below it are applied in dark gray color in the background in the top right corner of the picture. They were covered with a blue glaze, which was dissolved during cleaning and partially washed into the original craquelure. Letters filled and partially retouched. On some letters, there is a gray shadow tone on the side, which perhaps was intended to create a three-dimensional effect and the impression of an engraved inscription. Another filled signature is located in the cabinet on the right door: "Meer.". It is in light blue, and a darker gray-blue was applied over it. The craquelure, which partially closed like the other signature, is due to cleaning, especially affecting the first letter. However, both signatures are original and well integrated into the paint layer.

The geographer's robe

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (detail)

Jan Verkolje

c. 1680–1686

Oil on canvas, 56 x 47.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The geographer's contemplative pose is accentuated by an imported Japanese robe, which was a fashion trend in the Netherlands during the mid-17th century. A comparable robe is depicted in Jan Verkolje's portrait of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, a renowned Delft scientist. Both Van Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer shared a mutual fascination for optics. The custom of depicting scholars and artists in Japanese-inspired robes persisted into the 18th century. However, this choice of luxurious clothing doesn't necessarily indicate the real work attire of an artist.

Following their diffusion in the 17th century, this particular garment was called in many ways—Japonse zijde rok, schenkagierocken (gift gowns), keyserrocken (imperial gowns)—in VOC documents and other written sources, such as letters or inventories. By 1700, various names, such as chamberlouc, japon, nachtrok, nachttabbaard, and cambaay were used to describe the smae garment.

Portrait of Willem Pottey

Nicolaes Maes

c. 1686 - 1693

Oil on canvas, 61 x 49 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

This padded kimono-style garment was made according to Western tastes, which required larger proportions and favored a purely decorative arrangement of patterning. The blue silk—which includes Japanese parsley motifs and curious fake family crests—was woven, dyed, and stitched together in Japan before being shipped to a Western market. Few robes were intended for export, highlighting their preciousness. Compared to robes made for the domestic Japanese market, export robes are typically floor length, have wide sleeves, and are heavily padded, among other modifications. Many preserved export garments are made from colorful fabrics with eye-catching patterns, suggesting that European consumers preferred more conspicuous styles.

These robes, known as keizersrokken or Imperial kimonos, were esteemed gifts, typically bestowed in groups of thirty or more, to Dutch merchants privileged enough to visit the Imperial court in Edo, now Tokyo. Such visits were the only instances when these merchants could set foot on the Japanese mainland, as they were otherwise restricted to Deshima (also known as Dejima, a man-made island in the bay of Nagasaki, established in the early 17th century to regulate foreign interactions Japan had during its period of self-imposed isolation, known as Sakoku, which lasted for about 250 years from the early 17th to the mid-19th century). Consequently, these kimonos, also termed Japons, Japonsche rocken, Japonse rok or simply rok, weren't trade items in either Japan or Holland.

By the end of the century, the Japonse rok was not only a popular status symbol for wealthy commissioners but also an attribute for images of scholars and a mechanism for artists’ self-fashioning. Their ceremonial nature made them appropriate attire for indoor events and were often donned by scholars, enthusiasts, scientists, gentlemen and even city officials. The demand for these garments was so overwhelming that it exceeded what Japanese exports could provide. This led not only to the production of domestic replicas using imported fabrics but also prompted the VOC to start ordering chintz robes from India from 1684 onwards.

Many artists of the era also painted self-portraits wearing these robes. It wasn't until the mid-18th century that they were manufactured en masse in Europe using imported silk from India and China. In the context of Vermeer's painting, the geographer's attire is a distinct and non-commercialized fashion piece. The sharp folds and the vivid contrast between the robe's colors in the geographer's orange-trimmed rok engage the viewer's eye, subtly indicating the intensity of his intellectual pursuit. The dramatic representation of drapery in Vermeer's work became even more pronounced in his subsequent artworks.

By the end of the 17th century, the rok had grown so popular that regulations were established to prevent them from being worn in churches.

Unfinished?

More than one critic has suggested that The Geographer is unfinished. The wooden window frame, the carpet and the floor are defined in their essential features but lack the color and nuance characteristic of Vermeer's works from this period, especially when compared to The Astronomer, its presumed pendant.

The cupboard, presumably crafted from light-colored wood, appears indistinct, and the interplay of light and shadow on the decorative inlay seems particularly tentative.

It's conceivable that the cupboard was intended to store the geographer's various instruments and charts.

The chair in the background

This chair might very well be the same one depicted behind the table in Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Necklace and The Concert. The intricate floral designs (referred to in Dutch as "gezaeyde ofte gestroyde Bloemen") of the three chairs exhibit striking similarities.

Such chairs were likely produced in Delft. Their unique upholstery is seldom found in the works of artists from other regions. The Municipal Museum in Delft houses six of the original 41 chairs. These were delivered in 1661 by Maximiliaan van der Gucht, the renowned Delft tapestry weaver, to the Town Council, often referred to as "The Forty." Van der Gucht also crafted tapestries and chair cushions adorned with similar floral patterns. In 1661, he received a commission to design a series of tapestries and pillows featuring tulip motifs for the States of Holland.

A cross-staff?

Cross-staff, Northern Germany(?)

signed: L. Dankbaar, dated 1790

Ebony, brass 75.5 x 1,7 x 1.7 cm.

3 sliders (51 cm., 34 cm., 17 cm.)

with binding screws

Altonaer Museum Hamburg

- Norddeutsches Landesmuseum, Hamburg

Certain Vermeer scholars posit that what appears to be a section of the window grate might, in fact, be part of a Jacob's or cross-staff, even if its recognition proves challenging.

The cross-staff dates back to the early 14th century, though similar measuring devices can be linked to the Chaldeans around 400 B.C. This instrument was primarily employed to determine the angle of elevation of the sun and stars. Additionally, it was useful for gauging the heights of architectural structures and topographical features like mountains and hills. This made the cross-staff indispensable to both astronomers and geographers. While the Jacob's staff was relatively precise, its usability left much to be desired. The Holland circle (or circumferentor), introduced around 1605 by the Leiden surveyor Jan Dou, marked a significant advancement in this regard.

Kees Zandvliet notes that the instruments featured in The Geographer, including the Jacob's staff and compasses, were practical tools of the time. This suggests that Vermeer's subject wasn't merely a theoretical scholar. In fact, some speculate that the figure portrayed might be the Delft scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. Not only was he the inventor of the microscope and a pioneer in microbiology, but he was also a skilled surveyor.

The portrayal of such a practical instrument in Vermeer's work underlines the importance of empirical study and hands-on experience during the scientific awakening of the 17th century. The close association between art and science speaks to a broader theme of the Enlightenment era where observation, experimentation and reason were esteemed in multiple fields of inquiry.

Vermeer & Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza

Due to its relatively tolerant political and religious stance, the United Provinces attracted notable thinkers of the century, including John Locke and Baruch Spinoza. In their era, scientific discovery and observation took precedence as religious faith no longer provided complete guidance for everyone. Optical instruments, such as the telescope, microscope and camera obscura (which Vermeer was undoubtedly familiar with), were used to delve into the "anatomy of the universe." Moreover, the act of seeing itself became a topic of profound philosophical debate.

In recent times, several authors have sought to connect Vermeer's meticulous art and his interest in optics to these groundbreaking intellectual movements. Consequently, it is believed that Vermeer used the camera obscura not just as a tool for observing and recording visual details but for its philosophical connotations. Historian Robert Huerta has elevated the Delft artist to the status of a natural philosopher.

Vermeer and Spinoza shared some parallels. Both were born in 1632, with Spinoza passing away two years after Vermeer in 1677. Spinoza's Tydeman residence was a mere seven miles from Vermeer's home in Delft, approximately an hour and twenty-minute walk. While no evidence confirms that Vermeer was acquainted with Spinoza or that Spinoza's theories were a topic of discussion in Delft, the five folios and twenty-five diverse books mentioned in the artist's estate inventory suggest he was well-read. Though it remains unclear if Vermeer engaged with the scientific and philosophical debates of his era, he produced two compelling artworks, The Astronomer and The Geographer from 1668 to 1669, reflecting his respect for contemporary scientists.

Spinoza had an in-depth understanding of optical theory and the physics of light of his time. He actively participated in nuanced discussions with peers regarding the mathematics of refraction. Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, the renowned scientist and lens maker, likely knew Vermeer since both resided in Delft. It is plausible that Van Leeuwenhoek recognized Spinoza, either for his lens work or for his controversial views, especially during the late 1660s when Spinoza faced criticism. In Delft, the presence of luminaries such as Van Leeuwenhoek, Evert Harmansz Steenwijck—father of painter Pieter Harmansz Steenwijck, who crafted a telescope in 1610—and notary Jacob Spoors, who delved into mathematics, optics and astronomy, undoubtedly augmented local dialogues on optics, light and perspective. These were subjects that would undoubtedly pique the interest of an artist like Vermeer. This becomes even more evident when considering the importance of optical instruments, such as the renowned camera obscura, in the devotional teachings of the Jesuits—a connection recently highlighted by Vermeer scholar Gregor Weber.

Several authors have related Spinoza's commendation of the contemplative and intellectual life to the subjects in Vermeer's artworks, many of whom appear engrossed in deep contemplation or intellectual activities. From a structural perspective, Vermeer's compositions exude a unique sense of balance, suggesting that each element was deliberately and meticulously placed. As one writer observed, Vermeer's contemplative compositions represent the independent cognitive activities of his subjects. His inclination toward geometric forms has been indirectly associated with the subtitle of Spinoza's Ethics: ordine geometrico demonstrate (Ethics: Arranged According to Geometric Principles).

The white folio

Like the figure's face, the white surface of the paper has been overcleaned, so its purpose can no longer be identified.

The white-washed wall

Interior with a Woman Combing a Little Girl’s Hair

Jacobus Vrel

c. 1654/1662

Oil on oak panel, 55.9 x 40.6 cm.

The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit

Of all Dutch painters, only Vermeer and the relatively unknown Jacob Vrel (fl. 1654–1662), who has recently been proposed as a possible forerunner of Vermeer, placed significant emphasis on the background walls of their scenes.

Vermeer utilized the walls to delineate the intensity and direction of the incoming light and to establish a specific atmosphere congruent with the painting's intended meaning. He took particular delight in depicting the shadows cast upon them by paintings-within-paintings and adjacent furniture pieces. In The Geographer, the shadows thrown by the globe and cupboard are pivotal in merging the compositional elements to forge a cohesive whole. The pronounced diagonal of the cupboard's shadow intersects the lower corner of the ebony-framed nautical map, anchoring it to the composition, even though a significant portion of the map extends beyond the painting's right-hand edge. The vertical edge of the same shadow ends close to the silhouette of the background chair, allowing the slanting light to highlight the decorative pattern on the chair's upholstery and a narrow section of the wall to its left. The diffuse shadow projected by the globe is especially evocative.

The Delft floor tiles

In many Middle Eastern and southern countries, tiles were commonly used on floors or building exteriors for both decorative and protective reasons. However, in the Netherlands, the colder winters prevented such usage as tiles would deteriorate rapidly, especially when used for flooring due to the loss of their glazed imagery. Recognizing the durability of tiles in high temperatures, the Dutch initially employed them to line the interiors of their consistently sooty fireplaces, where they remained unaffected and were easily cleaned. Soon, they realized that these wall tiles could also shield their homes from humidity and stains, given the challenges in heating houses during that period. As prosperity grew, so did the demand for these tiles, with both tradesmen and farmers desiring their decorative appeal.

The inception of Delft tile designs can be traced back to a halt in Chinese porcelain imports during the mid-17th century. Dutch potters subsequently began crafting high-quality ceramic wares in blue and white, initially imitating Chinese motifs. Since the production of this pottery was concentrated around the city of Delft, it became known as Delftware, or Delft Blauw. While tiles weren't the primary focus of Delftware, they were still produced and exported in enormous quantities (an estimated eight hundred million) to countries like France, Germany, Russia, Spain and the Ottoman Empire over a span of two centuries. Remarkably, many Dutch homes today still retain tiles from the 17th and 18th centuries. Popular designs featured on these tiles included ships, windmills, scenes of children at play and various animals.

The Delftware production process was unique and involved multiple steps, including the application of a tin-glaze which gave it a distinct appearance. This tin-glaze made Delftware tiles different from the original Chinese porcelain, which had a different kind of sheen and finish. Over time, as Dutch potters began to master their craft, they diverged from the initial Chinese-inspired designs, incorporating more of their local culture and daily life into the tiles. This not only made Delft tiles a distinctive form of Dutch art but also a chronicle of life and society in the Netherlands during the 17th and 18th centuries.

In many Dutch paintings from this period, tiles are often arranged in a single row at the base of walls, serving as protection against the wear and tear from daily cleaning tools such as brooms and mops. Vermeer depicted floor tiles in five of his works. Contrary to the tiles in A Lady Seated and A Lady Standing at a Virginal, the tiles in The Milkmaid, Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid and The Geographer have a subtle blue hue. In The Geographer, the decorative motifs on the tiles are rendered so faintly that their designs are indiscernible. Meanwhile, the tiles in The Milkmaid are distinct in that they lack the corner flourishes present in The Geographer.

The sketchy floor

Unlike most of Vermeer's late works, The Geographer features a mundane nondescript floor. The sketchy character of this and other passages of the painting suggests that it may have not been completely finished.

special topics

The signatures

There are two signatures on The Geographer. Scholars once believed that this conspicuous signature on the background wall (with the date in Roman numerals) was not original even though the date, MDCLXVIIII (1669) was compatible with the date most Vermeer experts have ascribed to the painting. A recent restoration has demonstrated that both are original.

This signature on the cupboard is now esteemed to be authentic as the one above.

(Click here to access a complete study of Vermeer's signatures.)

Dates

1669

Albert Blankert, Vermeer: 1632–1675, 1975

c.1668–1669

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer, London, 1997

1669

Walter Liedtke, Vermeer: The Complete Paintings, New York, 2008

1669

Wayne Franits, Vermeer, 2015

(Click here to access a complete study of the dates of Vermeer's paintings).

Technical report

The support is a closed, plain-weave linen with a thread count of 14 x 11 per cm², the original tacking edges of which are still present. The canvas was lined, resulting in weave emphasis.

A gray ground containing chalk, umber and lead white extends to the tacking edges. The paint was applied wet-in-wet in places. Many different textural effects have been created with the use of glazing, scumbling, impasto and dry brushstrokes. The vanishing point of the composition is visible in the paint layer on the wall between the chair and the cupboard. Some abrasion, particularly in the shadows in the map, has resulted from past cleaning.

* Johannes Vermeer (exh. cat., National Gallery of Art and Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis - Washington and The Hague, 1995, edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr.)

Provenance

- (?) Adriaen Paets I, Rotterdam (?1669-d.1686);

- (?) his son, Adriaen Paets II, Rotterdam (1686-d.1712);

- sale (Paets et al.?), Rotterdam, 27 April, 1713, no. 10 or 11, sold together with The Astronomer;

- Hendrick Sorgh, Amsterdam (?1713-d.1720);

- Sorgh sale, Amsterdam, 28 March, 1720, no. 3 or 4, sold together with The Astronomer;

- Govert Looten, Amsterdam (before d.1727);

- Looten sale, Amsterdam, 31 March, 1729, no. 6, sold together with pendant of the same no. Jacob Crammer Simonsz, Amsterdam (by d.1778);

- Crammer Simonsz sale, Amsterdam, 25 November, 1778, no. 18, sold together with The Astronomer as pendant (to De Vries);

- Jean Etienne Fizeaux, Amsterdam (1778-d.1780);

- his widow, Amsterdam (1780-?1785);

- [Pieter Fouquet, Amsterdam, and Alexandre Joseph Paillet, Paris, 1784–85];

- Jan Danser Nijman, Amsterdam (?before 1794-d.1796);

- Danser Nijman sale, Amsterdam, 16 August, 1797, no. 168, sold separately (to Josi);

- [Christian Josi, Amsterdam and London];

- Arnoud de Lange, Amsterdam (?1797-d.1803);

- De Lange sale, Amsterdam, 12 December, 1803, no. 55 (to Coclers);

- Johann Goll van Franckenstein, Jr., Velzen and Amsterdam (before 1821);

- Pieter Hendrick Goll van Franckenstein, Amsterdam (before 1832);

- Goll van Franckenstein sale, Amsterdam, 1 July, 1833, no. 47 (to Nieuwenhuys);

- [Christian Johannes Nieuwenhuys, Brussels and London; sold to Dumont];

- Alexandre Dumont, Cambrai (before 1860–1866);

- Isaac Péreire, Paris, 1866 (sold via Thoré-Bürger from Dumont);

- Péreire brothers sale, Paris, 6 March, 1872, no. 132;

- (?) Max Kann, Paris (?1872);

- [Sedelmeyer, Paris, c. 1875; sold to Demidoff];

- Prince Demidoff di San Donato, near Florence (before 1877–1880);

- Demidoff sale, San Donato, 15 March, 1880, no. 1124 (to Bösch?);

- Adolf Josef Bösch, Döbling, Vienna (?1880-d.1884);

- Bösch sale, Vienna, 28 April, 1885, no. 32 (to Ludwig Kohlbacher of the Frankfurter Kunstverein on behalf of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut);

- 26 May, 1885 to the Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt am Main (inv. 1149).

Exhibitions

- Paris 1866

Exposition rétrospective tableaux anciens empruntés aux galeries particulières

Palais des Champs-Elysées

35, no. 106 - Paris 1874

Exposés au profit de la colonisation de l'Algérie par les Alsaciens-Lorrains

Palais de la Présidence du Corps léegislatif

60, no. 332 - Paris 1898

Illustrated catalogue of 300 Paintings by Old Masters of Dutch, Flemish, French and English School Being Some of the Principal Pictures Which Have at Various Times Formed Part of Sedelmeyer Gallery

Sedelmeyer Gallery

104, no. 87 and ill. - Paris 1914

Hundred Masterpieces. A Selection from the Pictures by Old Master

Sedelmeyer Gallery

54, no. 25 and ill. - Rotterdam 1935

Vermeer, oorsprong en invloed. Fabritius, de Hooch, de Witte

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

38, no. 87 and ill. 68 - Washington D.C November 12, 1995–February 11, 1996

Johannes Vermeer

National Gallery of Art

170–175, no. 16 and ill. - The Hague March 1–June 2, 1996

Johannes Vermeer

Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis

170–175, no. 16 and ill. - Frankfurt 1997

Johannes Vermeer: der Geograph und der Astronom nach 200 Jahren wieder vereint

Städelschen Kunstinstitut

no.1 - Osaka 4 April–2 July, 2000

The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer

Osaka Municipal Museum of Art

190–193, no. 35 and ill. - Kassel February 14–May 11, 2003

Johannes Vermeer: Der Geograph. Die Wissenschaft der Malerei (The Geographer. The Science of Painting)

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Museumslandschaft Hessen - Rotterdam October 23, 2004–January 9, 2005

Senses and Sins: Dutch Painters of Daily Life in the Seventeenth Century

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen - Frankfurt February 10–May 1, 2005

Senses and Sins: Dutch Painters of Daily Life in the Seventeenth Century

Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische Galerie - Bilbao October 7, 2010–January 23, 2011

The Golden Age of Dutch and Flemish Painting from the Städel Museum

Guggenheim - Aichi (Japan) June 11–August 28, 2011

The Golden Age of Dutch and Flemish Painting from the Städel Museum

Toyota Municipal Museum of Aichi - Budapest October 31, 2014–February 15, 2015

Rembrandt and the Dutch Golden Age

Szépművészeti Múzeum - Frankfurt October 7, 2015–January 24, 2016

Masterworks in Dialogue: Eminent Guests for the Anniversary

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main - St. Petersburg August 27–November 20, 2016

Johannes Vermeer: "The Geographer" fom the Städelsches Kunstinstitut (Masterpieces from the World's Museums in the Hermitage)

Hermitage - Paris February 20–May 22, 2017

Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry

Musée du Louvre - Dublin June 17–September 17, 2017

Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry

National Gallery of Ireland - Washington D.C. October 22, 2017–January 21, 2018

Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry

National Gallery of Art - Madrid June 25–September 29, 2019

Velázquez, Rembrandt, Vermeer. Parallel Visions

Museo Nacional del Prado

- Dresden June, 4–September 12, 2021

Vermeer: On Reflection

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden - Amsterdam February 10– June 4, 2023

VERMEER

Rijksmuseum

no. 30 and ill.

(Click here to access a complete, sortable list of the exhibitions of Vermeer's paintings).

| Vermeer's life | Vermeer signs and dates The Astronomer 1668. Some scholars believe that Delft citizen Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who was by then internationally recognized for his studies in optics and scientific observations, posed for The Astronomer, although portraits of Leeuwenhoek bears little resemblance to the seated man in Vermeer's picture. |

| Dutch painting |

Rembrandt paints Return of the Prodigal Son. Gabriel van de Velde paints Golfers on the Ice. Philips Wouwerman, Dutch painter, dies. He was the most celebrated member of a family of Dutch painters from Haarlem, where he worked virtually all his life. He became a member of the painters' guild in 1640 and is said by a contemporary source to have been a pupil of Frans Hals. The only thing he has in common with Hals, however, is his nimble brushwork, for he specialized in landscapes of hilly country with horses—cavalry skirmishes, camps, hunts, travelers halting outside an inn and so on. In this genre he was immensely prolific and also immensely successful. |

| European painting & architecture |

Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt, Austian architect, is born. Bernini sculpts a terra cotta study for one of the angels of Rome's Port Santa Angelo. |

| Music |

Nov 10, Francois Couperin, composer and organist (Concerts Royaux), is born in Paris, France. Danish organist-composer Diderik Buxtehude, 31, is named organist at the Marienkirche in Lübeck, succeeding Franz Tunder (whose daughter, Anna, he marries). His sacred Abendmusiken concerts will be presented each year during Advent on the five Sundays before Christmas. Buxtehude's cantatas and instrumental organ work will have a strong influence on other composers. Mar 5, Francesco Gasparini, composer, is born. |

| Literature |

Apr 13, John Dryden (36) became 1st English poet laureate. |

| Science & philosophy |

Robert Hooke: Discourse on Earthquakes. Newton invents the reflecting telescope, building the first telescope based on a mirror (reflector) instead of a lens (refractor). First accurate description of red corpuscles by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. Leeuwenhoek was born in the same year as Vermeer and is often associated to the artist for their interest in optics. Chemist Johann R. Glauber dies at Amsterdam March 10 at age 63. |

| History |

Mar 26, England takes control of Bombay, India. Mar 27, English king Charles II gives Bombay to the East India Company. Sep 16, King John Casimer II of Poland abdicates his throne. Louis XIV of France purchased the 112 carat blue diamond from John Baptiste Tavernier for 220,000 livre. Tavernier is also given a title of nobility. Feb 7, The Netherlands, England and Sweden conclude an alliance directed against Louis XIV of France. |

| Vermeer's life |

Vermeer's mother, Digna Baltens, leases the inn Mechelen to a shoemaker for three years. She and her husband had worked in the place for 28 years. Afterward, she goes to live with her daughter Gertruy on the Vlamingstraat, in Delft. Vermeer and his wife bury another child in the Old Church. Pieter Teding van Berckhout, from an important family in The Hague, visits Vermeer twice and enters in his diaries his impressions. In May 14, 1669, Van Berckhout writes: "Having arrived in Delft, I saw an excellent painter named Vermeer," stating also that he had seen several "curiosities" of the artist. He had arrived in Delft accompanied by Constantijn Huygens and his friends—member of parliament Ewout van der Horst and ambassador Willem Nieupoort. Huygens was an artistic authority in his own day, maintaining contacts with the famous Flemish painters Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck and recording in his own diary some remarkably insightful comments about the art of, among others, Rembrandt van Rijn. Van Berckhout must have been deeply impressed by the work he saw in Vermeer 's studio, since he returned for another visit less than a month later. On June 11, Van Berckhout notes: "I went to see a celebrated painter named Vermeer" who "showed me some examples of his art, the most extraordinary and most curious aspect of which consists in the perspective." This time Van Berckhout used the term "celebrated" rather than "excellent" in describing Vermeer. This testifies Vermeer had achieved a rather considerable reputation. What is most interesting about this visit is that Vermeer's studio (like Dou and van Mieris) had evidently evidentbecome a major cultural destination. |

| Dutch painting | Oct. 4, Rembrandt dies, eleven months later after his son, Titus, in 1668—only 27 years of age. His beloved Hendrickje had died in 1663. |

| European painting & architecture |

Le Vau begins remodeling Versailles. The semicircular Sheldonian Theater at Oxford, England, designed by Christopher Wren, is completed. |

| Music |

Royal patent for founding Academie Royale des Operas granted to Pierre Perrin. Marc' Antonio Cesti, Italian composer, dies. The first Stradivarius violin is created by Italian violinmaker Antonio Stradivari, 25, who has served an apprenticeship in his home town of Cremona in Lombardy to Nicola Amati, now 73, whose grandfather Andrea Amati designed the modern violin. The younger Amati has improved on his grandfather's design and taught not only Stradivari but also Andrea Guarnieri, 43, who also makes violins at Cremona. |

| Literature | |

| Science & philosophy |

Arnold Geulincx (b. 1624), Dutch philosopher, dies. Nicolaus Steno (1638–1687) begins the modern study of geology. Nils Steensen's Prodromus is first published in Italy and translated to English two years later. It explains the author's determination of the successive order of the earth strata. Emperor Leopold I sanctions the foundation of a higher school in Innsbruck, Austria. This is considered to mark the founding of the University of Innsbruck. A General History of the Insects by Jan Swammerdam presents a preexistence theory of genetics that the seed of every living creature was formed at the creation of the world and that each generation is contained in the generation that preceded it. |

| History |

Pope Clement IX dies at Rome December 9 at age 69 after a 2½-year reign in which he has encouraged missionary work, reduced taxes and extended hospitality to Sweden's former queen Kristina. He will not be replaced until next year. Feb 1, French King Louis XIV limits the freedom of religion. Mar 11, Mount Etna in Sicily erupts killing 15,000. Sep 27, The island of Crete in the Mediterranean Sea falls to the Ottoman Turks after a 21-year siege. |

Tolerance in 17th-century Netherlands

The opening page of

Ethica

Baruch Spinoza

It is generally accepted that upon Vermeer's wedding to Catharina Bolnes, the artist converted to Catholicism. We have no objective evidence that his conversion—an extremely rare event in the Netherlands—caused him any undue difficulties during his career. He lived with his Catholic mothered-in-law, Maria Thins, in the Catholic "Papist's Corner" in Delft and brought up his children according to the Catholic faith. While religious conversion in the Netherlands was frowned upon, it was nonetheless tolerated.

While not free from religious conflict, the Netherlands had a long tradition of religious tolerance. The Union of Utrecht, signed on 23 January 1579, declared individuals free to choose their own religion. For centuries the Dutch Reformed Church was the privileged church, but other denominations were allowed to perform their worship services. The Dutch Republic became a refuge for religious and political dissidents from abroad, including such groups as Jews and Huguenots, as well as such noted individuals as Baruch de Spinoza and René Descartes. In combination with a vibrant commercial culture and schools that were developing excellent reputations, this tolerant society provided fertile soil for cultivating a scientific way of looking at the world.

However, tolerance did not reside in a coherent body of law although Dutch intellectuals vigorously discussed the foundations of their new republic. More generally, the climate of lenience and a free press allowed thinkers like Coornhert, Grotius and Gerard Noodt, as well as foreign residents or visitors like Bayle and Locke, to explore the philosophical properties of tolerance. However, there were clear boundaries beyond which they could not venture.

Spinoza and his followers discovered that freedom of conscience did not mean freedom of thought. They risked censure and punishment especially when their works were seen as undermining the Christian foundations of the Republic. Despite such limitations, it was precisely this philosophical speculation that over time helped the Netherlands to serve as a model elsewhere.

Who posed for the painting?

Anthonie van Leeuwenhoek (detail)

Jan Verkolje

c. 1680–1686

Oil on canvas, 56 x 47.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In the construction of The Geographer, Vermeer was most likely guided by someone familiar with geography and navigation as demonstrated by the artist's sophisticated description of the scientific instruments. Moreover, none of these expensive instruments are mentioned in the artist's death inventory of movable goods. In Delft, Anthoni van Leeuwenhoek was well known for his discoveries with the microscope but was also described as being skilled in "navigation, astronomy, mathematics, philosophy and natural sciences." He was born in Delft in 1632, the same year as Vermeer. Some experts believe it was Van Leeuwenhoek who posed for both The Geographer and The Astronomer and perhaps commissioned them too. A portrait by Delft painter Jan Verkolje shows the scientist when he was fifty-four years old, some eighteen years after Vermeer's painting. Whether or not the features are similar to the long-haired scholar in Vermeer's painting is debatable.

The art of 17th-century mapmaking

Cartography is one of the oldest human occupations. It evolved to a high standard of science, technology and art, especially from the Renaissance and onward; its peak was reached in the 17th and 18th centuries. The historian R.S. Westfall has demonstrated that almost "two out of five" scientists were then dealing with cartography.

Portrait of Map-makers, Gerard Mercator and Jodocus Hondius

Jodocus Hondius

1613

Color on engraving, 37.7 × 44 cm.

National Museum in Warsaw, Warsaw

The Dutch were then world leaders in the field of cartographic production: globes, maps, charts and atlases were issued in unprecedented quantities during the 17th century in the Netherlands, with its main production center in Amsterdam. In Vermeer's time, mapmaking and painting were not clearly distinct disciplines as they are today. 17th-century mapmakers required a combination of skills. Other than a thorough knowledge of surveying, the mapmaker had to know how to draw, watercolor and create decorative motifs. If the maps were to be reproduced, he had to be thoroughly versed in engraving, printing, calligraphy and marketing techniques as well.

Such sophisticated products remained expensive so the number of specialists remained small. Elaborate, decorative maps, like those in Vermeer's paintings, were sold alongside books in specialty shops on Binnenhof in The Hague and around Dam Square in Amsterdam. But there are numerous testimonies that simple citizens were inclined to make maps of their own.

Floris Balthasar, a mapmaker, citizen of Delft and member of the Guild of Saint Luke of Delft, would have regarded himself as a cunstwerker in caerten, an artist in mapmaking.

Balthasar pointed out the dual functions of the map. On one hand they could be used for military operations, for architecture, for hydraulic works, for sea trade and for questions of land ownership. On the other hand, maps could be collected to increase knowledge of the world, insight into history and the joy of learning of God's creation of the world.

Why & for whom were globes made?

Terrestrial Globe

Jacobus Hondius

1618

The initial impetus for developing and manufacturing globes as a commercial enterprise was provided by a desire for geographical information in the period of the great discoveries. Although their decorative function must have been an important concern, in general, globes were constructed with the stated aim of promoting geographical and astronomical studies recording the latest geographical and astronomical information. Once a globe was made it was complicated and expensive to correct the engraved copper plates in order to print new versions. Thus, while most globes exhibit an up-to-date geographical picture when the plates were first engraved, for years to come they were rarely altered so that the majority of existing globes was out-of-date.

In order to commercialize their globes, manufacturers advertised them as scientific aids for navigation, especially in the 16th and early 17th centuries. Jacob Hondius, the producer of the globes in Vermeer's paintings, gave this as a reason for making globes although seamen rejected them due to the difficulties involved in making accurate measurements around a curved surface.

Nonetheless, the globe became a symbol more than a tool of navigation, and therefore an object desired by Dutch merchants. This side-effect not only stimulated an expansion in globe production, it also made it possible to sell out-of-date globes. Those who purchased globes for their symbolic value were far less concerned about their scientific accuracy than its decorative aspect. At times, globes were sold that were constructed more than a century ago.

Vermeer & Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza

Owing to its relatively tolerant political and religious attitude, the United Provinces had become a magnet for some of the great thinkers of the century, such as John Locke and Baruch Spinoza. Theirs was an age of observation and scientific discovery in which religious faith was no longer sufficient guidance for all men. Optical instruments, such as the telescope, microscope and camera obscura (Vermeer certainly knew the latter) had become means to scrutinize the "anatomy of the universe" and sight itself had become an issue of intense philosophical speculation.

In recent years, various writers have endeavored to link Vermeer's measured art and his concerns with optics with these revolutionary intellectual currents. Accordingly, the artist would have employed the camera obscura not merely as a mechanical means for studying and transcribing outward appearances but for its philosophical implications. The historian Robert Huerta promoted the Delft artist to the role of the natural philosopher.

Vermeer and Spinoza had some things in common. Spinoza was born in the same year as the artist, 1632, and died in 1677, two years after Vermeer. Spinoza's Tydeman home, just an hour twenty-minute walk to Vermeer's house in Delft, was seven miles away. There is no proof that Vermeer knew Spinoza or even if Spinoza's ideas were discussed in Delft but in the age when books were still expensive commodities, five folios and twenty-five assorted books reported in the inventory of the artist's estate testify that he was not unlearned. Whether or not Vermeer occupied himself with the scientific and philosophical debates of the time remains uncertain but he left two powerful images which al least show his admiration for the scientists of his time, The Astronomer and The Geographer painted between 1668 and 1669.

Spinoza had a solid grasp of optical theory and of the then-current physics of light, and was competent enough to engage in sophisticated discussion with correspondents over fine points in the mathematics of refraction. We know that Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, the distinguished scientist and lens-grinder, almost certainly knew Vermeer since both lived in Delft. We would expect Van Leeuwenhoek was aware of Spinoza's reputation for either for his work with lenses or for and free-thinking heresies which came under fire in the late 1660s.

Some writers have associated Spinoza's praise of the contemplative and intellectual life as the highest of man's achievements with the people that appear in Vermeer's paintings, many of whom are pictures absorbed in rapt contemplation or engaged in intellectual pursuits. From a formal point of view, Vermeer compositions have an uncommon air of equilibrium as if every element had been examined and exactly ordered within the perimeters of his composition according to some unknown plan. As one author wrote, Vermeer's thoughtful compositions stand for the independent mental activity of his figures. His penchant for geometrical forms has been indirectly linked to the subtitle of Spinoza's Ethics, ordine geometrico demonstrate (arrange according to geometric principles).

The scholar-in-his-studio motif

Saint Jerome in His Study

Albrecht Dürer

1514

Engraving,sheet: 24.6 x 18.9 cm. trimmed on plate line

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Scholars have been a recurring motif in Dutch art, with their portrayal tracing back to the 16th-century depictions of St. Jerome, immersed in contemplation within his study. This theme gained significant traction in the 17th century, possibly influenced by the early works of Rembrandt, who represted biblical figures engrossed in scholarly debates and lively discussions. This motif was particularly embraced by painters from Leiden.

Albrecht Dürer, the renowned German artist of the Northern Renaissance, created the engraving St. Jerome in His Study in 1514. This work is one of Dürer's master engravings, often referred to as his Meisterstiche or "master engravings," alongside Melencolia I and Knight, Death, and the Devil.

A Scholar at his Desk

Frans van Mieris the Younger

1717

Oil on oak wood, reverse original, beveled on all sides, 30.2 x 25.0 cm.

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

A notable example is of the scholar in his studio is The Scholar by Frans van Mieris the Younger, painted in 1717. Once part of the Städel collection, this work offers a later interpretation of the scholarly theme. The painting is replete with symbols of academic pursuit: books, piles of paper, globes, and writing instruments, which were standard elements in such depictions. An engraving of Admiral Michiel Adriaensz. de Ruyter on the wall underscores the practical application of scientific knowledge during the Age of Discovery. The presence of a terrestrial globe hints at the era's advancements in cartography, which played a pivotal role in unveiling uncharted territories.

Similarly, Vermeer's Geographer is adorned with quintessential scientific tools. Rolls of paper, books, and instruments like the Jacob's staff by the window and the set square on a stool are discernible. The map, showcasing the coasts of Europe by Willem Jansz. Blaeu, first published in 1600, and the globe, identified as Jodocus Hondius's 1618 terrestrial globe, both underscore the emphasis on scientific exploration and knowledge during that period.

Pentimenti: hidden stories

Vermeer is known for his meticulous compositions and attention to detail. Like many artists of his time and earlier, he occasionally changed his mind during the painting process, leading to pentimenti, or alterations, in his works. These changes can sometimes be detected through the naked eye, but often they are revealed through modern techniques like X-ray and infrared reflectography.

A "pentimento" (It., plural, "pentimenti") refers to visible traces of earlier work in a painting, indicating that the artist changed their composition during its creation. These alterations are crucial to art historical research because they offer insights into the artist's creative process, aid in authenticating artworks, reveal the evolution of artistic ideas, and, with modern technology, can be detected even beneath layers of paint. They also provide context about the historical and cultural environment in which an artist worked. Essentially, pentimenti give researchers a deeper understanding of an artist's intentions and the artwork's history.

The only painting by Vermeer that shows no evidence of pentimenti is the grandiose Art of Painting. The Geographer presents various pentimenti visible to the naked eye, some to a greater and some to a lesser degree, which allow us a glimpse of the artist's thought process.

The vague shape of the geographer's forehead can be seen to the left of the figure, an indication that the artist originally portrayed his head at a different angle, presumably looking down at the chart lying on the table. Vermeer also altered the position of the dividers: they originally pointed downward rather than across the geographer's body, which suggests not the active component of the geographer but his contemplative side. Finally, Vermeer eliminated a sheet of paper that once lay on the small stool at the right, probably to darken the right foreground corner of the composition. Another means by which Vermeer conveyed the geographer's active nature was through the crisp, angular folds of his blue robe. Vermeer used these remarkably abstract folds only to describe the sunlit blue robe: the broad, rolling folds of the floral table covering in the foreground are closer to the carefully modulated folds of the yellow jacket in A Lady Writing, painted a few years earlier. Thus, in The Geographer Vermeer seems to have selectively introduced this technique of modeling drapery, which becomes an important characteristic of his late style, to enhance the dynamics of his image.

Arcangelo Corelli

Arcangelo Corelli