In the past decades much ink has flowed concerning Vermeer's religious convictions. It now seems settled among the majority of historians that the young artist converted to Catholicism upon his marriage to Catharina Bolnes (1593–c.1676) even though the documentary information in regard is circumstantial.

In the case that Vermeer did indeed convert, did he do so to placate his influential, strong-willed mother-in-law, Maria Thins or was his conversion a spontaneous one dictated by spiritual necessities? It is improbable that we will ever know. Most likely, it was a good decision for both families. In order to fully comprehend what it meant to be converted to Catholicism and the serious personal and public consequences of such a decision, we must also take a brief look at the religious and political environment in Delft of the time.

Vermeer's Catholic Marriage

Vermeer's parents were married in 1615, in Amsterdam before Jacobus Taurinus, a famous Calvinist and Orthodox Reformed Church Minister. Although their marriage arrangement would seem to imply a commitment to the Reformed faith, neither of them was officially registered as a member of the faith which would have given them the right to participate in the sacrament of communion and an obligation to educate themselves in the doctrinal issues as well as a public confession of faith. Thus, it seems probable that Vermeer's parents belonged to a sizable group of people called liefhebbers (supporters), or those who for one reason or another did not comply with the strict requirements of membership or had a dislike for religious discipline.

Although nothing is known of Vermeer's religious thoughts before his marriage, we know for certain that he was baptized on October 31, 1632 in the Reformed Church in Delft.

Vermeer's mother-in-law, Maria Thins (1593–c.1680), was a devoted Catholic, and was most likely instrumental in the painter's conversion. She was a Delft patrician with excellent family ties who had grown up in Gouda, a stronghold of Dutch Catholicism. There, her family celebrated mass secretly in their home, De Trapjes (The Little Steps). Her sister had become a nun in Louvain.

Although not common, religious conversions happened. The renowned Dutch poet Joost van den Vondel converted. Maria Tesselschade, the talented daughter of Roemers Vischer and a friend of Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), became a Catholic in 1642, causing much grief to Huygens who went so far as to write a poem in protest.

Perhaps Vermeer's conversion was inevitable. The Council of Trent (1545–1563) had decreed matrimonial unions between Catholics and non-Catholics null and void. Thus, the marriage between Catharina as a Catholic and Vermeer as a non-Catholic would not have been accepted by the Catholic Church as a union in the understanding of the Catholic Church. According to the Council of Trent, the Roman Catholic Church had always taught the dogma of the Holy Matrimony as part of the Seven Sacraments, contrary to the Protestant Church (see Martin Luther, "Von den Ehesachen" Wittenberg 1530). The apostolic vicar to the Netherlands, Phillip Rovenius, writing in 1648, equated the marriage of a Catholic to a nonbeliever to a pact with the devil.

However, since Vermeer was already baptized, only a short consecrating act would have been necessary to convert to Catholicism together with basic lessons in the Catholic faith. Each new "soul" was warmly welcomed by the Catholic Church, even in times of repression. Since priests operated in utmost secrecy, it is not difficult to understand why notations of conversion have not survived.

Since Vermeer was not a full member of the Reformed Church, he would have found little motivation to refuse conversion which would have caused serious problems to his new family.

On the evening of April 4, 1653, the well-known Delft painter, Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674), a Roman Catholic, and Bartholomeus Melling, a Protestant sea captain, called on Maria Thins. They had with them a Delft lawyer named Johannes Ranck. This party had come to convince Maria that the up-and-coming artist was a good match for her beloved daughter Catharina. Maria's sister was also present giving support and sympathy. "The visitors had come to ask Maria to sign a document permitting the marriage vows to be published. Maria replied that she would not sign such an act of consent. Despite this—a subtle distinction—she would put up with the vows being published: she said several times that she wouldn't stand in the way of this. In other words, she didn't welcome the marriage, but she wouldn't block it. (Click here to view the original document.)

Next morning the notary Ranck drew up a deed attesting to Maria Thins' sufferance of the vows being published, and this was witnessed not only by Bramer and Mellling but by a man named Gerrit van Oosten and Delft lawyer Willem de Langue, who had frequent dealings with the Bramer and Vermeer family. De Langue had a significant collection of paintings including works of Rembrandt and Bramer.

Maria most likely wished to follow the advice of local Catholic officials who advised parents to attempt to dissuade children from marrying non-Catholics. One gains from this unusual glimpse into the private life of Vermeer: the aspiring young painter had evidently earned the favor of respectable men of the arts and high-standing Delft citizens.

Vermeer's marriage is recorded in a second document of April 5, 1653 with a marginal notation citing the small town Schipluy—today's Schipluiden—as the place where the union took place. Although the marriage banns were published in Delft, the young couple had requested a certificate allowing them to be joined in Schipluy (where Catholicism remained well entrenched. Catholic marriages could not be celebrated openly. Barns or other inconspicuous locales had to make do. When Vermeer married Catharina Bolnes, in essence, he became de facto part of a Roman Catholic family and a Roman Catholic neighborhood with its advantages and disadvantages.

After Vermeer married, he seems to have distanced himself from his own family. None of his children took their names from his side of the family as was customary. Instead, the name of Maria was given to the first child in honor of Maria Thins and the Virgin Mary. Another daughter Elizabeth, was perhaps named after Catharina's aunt who had become a nun in Flanders. Another child, Ignatius, no doubt, was given in honor of Saint Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order. Vermeer's first son Johannes eventually became a priest.

Although Vermeer's own family was situated beneath the social status of the Bolnes'—in such a small town as Delft Maria Thins must have known that Vermeer's grandfather had been involved in a counterfeit ring and had barely escaped beheading—the budding young painter seems to have placated her anxieties which were more than justified. Maria's own marriage had been full of domestic violence and ended with a divorce. Perhaps the close ties that Maria Thins' family had with the successful Delft painter Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674) guaranteed the artist's prospects.

In any case, it would appear that Maria comprehended Vermeer's artistic calling. Throughout the couple's married life, she consistently enhanced her daughter's financial position and supported the young painter's activity. A few paintings from her personal art collection appear in the background of her son-in-law's compositions and it is likely that some of the more costly props were Maria's possessions. And, the fact the couple paid no rent when they moved into Maria Thins' home in the first years of Vermeer's career, must have helped to stabilize his economic position in a fickle art market and permit him the luxury of painting as slowly and carefully as he wished.

It seems fair to say that Vermeer's Catholicism did not bring the painter any notable professional disadvantages. Catholic painters like Jan Steen (c. 1626–1679) prospered. The Protestant church did not commission paintings: Dutch artists depended almost exclusively on the open competitive market for their livelihood. Vermeer was elected as the head of the powerful Delft Guild of St Luke two times. His principal patron, Pieter van Ruijven, who had purchased about half of the artist's output, was probably Remonstrant. On the other hand, the ties offered by Maria Thins and her Catholic entourage must have secured the artist good connections with the cultural elite of Delft and beyond.

Catholicism in Vermeer's Art

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 114.3 x 88.9 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

There has been considerable disagreement among scholars concerning Vermeer's zeal for his adopted faith. Paul H. A. M. Abels (1996), for example, believes that the artist's conversion to Catholicism was somewhat superficial.Paul Abels, "Church and Religion in the Times of Vermeer," in Dutch Society in the Age of Vermeer (Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, 1996). The last testament of Maria de Knuijt, the wife of Vermeer's likely patron, Pieter van Ruijven, stipulated that Vermeer would receive five hundred guilders from her estate, unless the painter died before she did. Abels interpreted this bequest as an attempt to prevent the money from falling into the hands of Vermeer's wife and, ultimately, the hated Jesuits. Abels speculates that De Knuijt, who was strongly inclined toward the Reformed faith, did not consider this a danger if Vermeer himself received the inheritance, perhaps because the artist was less committed to the Catholic faith than his wife. He suggests that there exists a sort of "twentieth-century desire to fit Vermeer into one of the denominational pigeonholes" and that concrete evidence shows that Vermeer lived in a Catholic social milieu but it is far from certain how deeply his life or art was effectively influenced by it.

On the other hand, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., writing in the exhibition catalog for Washington, D.C., Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Ben Broos, Johannes Vermeer (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 86-88, 190. and Montias (1998), John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 103-104. argue that Vermeer was indeed a zealous Catholic.

Recently, the Vermeer specialist Gregor Weber has uncovered a wealth of circumstantial evidence that ties Vermeer to the Catholic faith much closer than previously believed in his recent book Johannes Vermeer: Faith, Light, and Reflection, Gregor Weber, Johannes Vermeer: Faith, Light and Reflection (Rotterdam: nai010 publishers, 2023). arguing that the Delft Jesuits played a major role in Vermeer's working practice and iconography. According to Weber, the property inventory drawn up after Vermeer’s death reveals that he aspired to lead a Catholic domestic lifestyle. On the wall of one room at his home—which he shared with his Catholic wife, mother-in-law, and a large brood of children—hung a large painting depicting the crucifixion of Christ, alongside another of Saint Veronica with the cloth she used to wipe the sweat and blood from the face of Jesus. Devotional art of this kind is typical of a Catholic prayer room.

Moreover, through a meticulous analysis of heretofore undiscussed literature and imagery, Weber advances that Vermeer was thoroughly acquainted with Jesuit devotional literature and suggests that he may have been introduced to the camera obscura by the Jesuits, although the device was known among artists, scientists, and intellectuals of the time. Additionally, the influential painter and art theoretician Samuel van Hoogstraten learned about the camera obscura from the Jesuits during his time in Vienna in the 1650s.

Weber also revealed for the first time that the Jesuits "considered the camera obscura a model of the human eye and therefore able to illustrate the process of vision and simultaneously the workings of light as a metaphor for God. In this connection, the camera obscura was even the subject of a Sunday sermon, in which the scientific background was discussed as well as the beauty of its projection, which was said to be superior to any painting."Gregor Weber, Johannes Vermeer: Faith, Light and Reflection (Rotterdam: nai010 publishers, 2023), 112. Vermeer certainly had contact with his Jesuit neighbors on the Oude Langendijk and such thoughts would very likely have occupied his thoughts.

But what do Vermeer's actual paintings tell us about his faith? Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. holds that the young Vermeer was the author of a rather large Saint Praxedis, a copy of an Italian painting whose Catholic subject is certain. He wrote that this early Saint Praxedis "has raised our appreciation of the seriousness of Vermeer's commitment to his new faith and its implications in his art." However, Wheelock's attribution has been heatedly debated, a fact which indirectly undermines his suppositions concerning the intensity Vermeer's religious belief. Wheelock presented a compelling argument to support his claim of Vermeer's authorship of the painting, noting that the artwork had two distinct signatures and a date, all integral to the paint surface. The second signature was interpreted as "Vermeer after Riposo," referring to Ficherelli's Italian nickname. Furthermore, laboratory analysis suggest that the painting's materials and techniques are consistent with seventeenth-century Dutch practices, including those of Vermeer. Wheelock emphasized the Dutch character of the modeling in the painting, particularly in Saint Praxedis' face.

However, his claims faced criticism from other scholars who challenged the authenticity of the signatures and the interpretation of the second signature as an allusion to Riposo. Some argued that the "Meer 1655" inscription was added after the painting was completed, making it non-integral. Jørgen Wadum, the former chief curator of the Mauritshuis, presented evidence that the second signature was not even visible to some specialists, argueing that the painting was not a copy of the work in Ferrara, or indeed of any other work, because the background elements were painted before the foreground, as is typical of an original work rather than a copy. Additionally, Marten Jan Bok, an expert on seventeenth-century Utrecht painter Johannes van der Meer, disagreed with Wheelock's interpretation, stating that such inscriptions were not typical in seventeenth-century Dutch copied paintings.

In 2014, the London-based auction house Christie's, which was charged to sell the painting, put forward the argument that this could be explained as experimentation by Vermeer, the young artist trying to recreate and adapt the technique used to create the original. In 2023, the Rijksmuseum conducted a new technical analysis and confirmed it to be a work of Vermeer.

In a complex, subtle analysis of religious life in Delft and the effect it had on Vermeer,Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Ben Broos, Johannes Vermeer (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 86. art historian Valerie Hedquist suggests that Vermeer's conversion had a deep impact on his art. Hedquist not only explores the Allegory of Faith (fig. 1) with its obvious Catholic associations, but the more enigmatic Woman with a Balance in the light of early Netherlandish traditions and religious symbolism. Vermeer would have represented ideas familiar to seventeenth-century Dutch Roman Catholics such as traditional Marian symbolismMarian symbolism encompasses a variety of symbols associated with the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus, and is frequently employed in art, literature, and Catholic devotions to represent her qualities and virtues. These symbols include the Immaculate Heart, symbolizing her love, compassion, and sorrow; roses denoting her purity; the Star, signifying her guidance; the Crescent Moon, highlighting her perpetual virginity; a blue Cloak or Mantle, symbolizing her protection and queenship; Lilies, representing her purity; Sun Rays, emphasizing her divine grace and role as the "Mother of Light" and the color blue, symbolizing heavenly grace and truth. These symbols collectively enrich the understanding of Mary's significance in Catholic traditions. dear to the Catholic faith. The young pregnant woman stands in for the Virgin Mary surrounded by Marian attributes such as the pearl and the mirror. According to Hedquist, the Allegory of Faith suggests that Vermeer depicted a genre scene that served as a domestic church setting where the eucharistic miracle of transubstantiation (the real presence of Christ's body and blood in the bread and wine of the Eucharist) is celebrated.Transubstantiation is a doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church that describes the change of the substance of bread and wine into the substance of the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ during the consecration in the Mass. This change is believed to occur at the moment the priest recites the words of institution: "This is my body" and "This is the chalice of my blood." The Catholic Church teaches that after the consecration, while the appearances of bread and wine (their "accidents") remain the same (i.e., they still look, taste, and feel like bread and wine), their substance is changed into the actual Body and Blood of Christ. Through transubstantiation, Christ becomes truly present in the Eucharist. This presence is not symbolic but real, though in a sacramental form. Additional pictorial and iconographic evidence supports the identification of the richly attired woman in Vermeer's painting as the penitent saint Mary Magdalen, representing the figure of faith.

Weber, a dedicated advocate of the Jesuit-Vermeer connection, contextualizes Vermeer's ostensibly non-religious work, Woman Holding a Balance, within the wider context of Jesuit doctrines. In doing so, he offers numerous fresh and compelling insights, delving into topics such as the Last Judgment's role in Southern Netherlandish Catholicism and the influence of Jesuit writings on the deliberate darkening of the depicted space in this artwork. Nevertheless, in the opinion of the arthistorian and Vermeer expert Wayne Franits, Weber's "otherwise persuasive findings beg the question of why Vermeer’s patrons, Pieter van Ruijven and Maria de Knuijt, whose beliefs were Remonstrant and Reformed, respectively, would desire a Catholic subject for their art collection. Did they just passively accept everything that Vermeer had to offer? Or did they sometimes assert their wishes in connection with specific pictures, which must have been commissioned?"

Franits casts doubts on Weber’s readings of Vermeer’s genre paintings representing a Woman with a Pearl Necklace and Young Woman with a Water Pitcher. "As to the former, we are told that 'it fits seamlessly into the iconography of Jesuit devotional books…,' several of which are illustrated in the text. But all of these book illustrations combine a woman at a mirror with saints or angels (and in one, with Christ carrying the cross). Such imagery is conspicuously absent in Vermeer’s canvases. The same can be said of the Young Woman with a Water Pitcher. Therefore, neither picture provides the requisite corroborative visual evidence to support Weber’s moralistic, Jesuit-based readings."

Without shadow of doubt, Vermeer's late Allegory of Faith, a picture drawn from Cesare Ripa's Iconologia (a widely circulated manual for painters)Cesare Ripa's Iconologia is a significant work in the realm of emblem literature and iconography. It was authored by Ripa in the late 16th and early 17th centuries and serves as a dictionary of allegorical symbols. This work, initially published in 1593 and later expanded with illustrations, was immensely influential in the visual arts, particularly during the Baroque period. Artists used "Iconologia" as a reference to infuse their works with symbolic meaning, and it provided a standardized set of symbols and attributes. Ripa's legacy extends beyond art, as the work offers valuable insights into the intellectual and cultural landscape of the Renaissance and Baroque eras, making it a significant resource for historians and scholars. is a rather clear-cut allegory of the Catholic faith. Here, modern critics underline the contrived nature of the picture and most place it among Vermeer's weakest works. It is hardly a favorite of the public either even though it contains passages of exquisite pictorial facture. However, the assumed lack of artistic participation should be taken with caution. Taste in style and subject matter changes insidiously through the centuries. It would appear that Vermeer's contemporaries thought very differently about the painting. In a posthumous sale, the Allegory of Faith was described as "powerfully and glowingly painted," a statement which was backed-up by the considerable sum it was able to fetch, the highest documented sum for a Vermeer painting sold in the years during or shortly after the end of the artist's activity.

Other critics have speculated that the Allegory of Faith was a work commissioned by some rich Catholic and, as such, was executed according to strict iconographical directives. This kind of participation had produced the bulk of the great Italian masterpieces and certainly, in the time of Vermeer, would not have been necessarily considered obsequiousness on the part of the artist. The most obvious candidate would have been some member of the Jesuit community, perhaps as payment of a sort of moral debt contracted earlier, or simply as an opportunity to make some money in the years of extreme economic hardship for the citizens of Delft and the United Provinces.

In any case, scholars are not in agreement why the scene unfolds in a fashionable Dutch Interior. John Montias has speculated that the artist's home may have served as a place of worship.

Catholicism in the Netherlands

William the Silent (1533–1584) and his followers' goal was that his countrymen could worship openly in an environment of religious tolerance. A peaceful coexistence prevailed in Delft for several months in 1572–1573. Catholics worshiped in the Oude Kerk (Old Church) while Protestants worshiped in the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church). However, Willem's dream of religious tolerance was short-lived. Soon after, violence forced to Catholics to give up their place of worship. This intolerance may perhaps be rooted in the fact that the Dutch rebellion against the brutal Spanish oppression had been perceived as a battle against a southern enemy whose leaders were encouraged by the Pope in Rome. When William the Silent was assassinated by a Catholic zealot,Balthasar Gérard was the assassin of William the Silent, Prince of Orange, a key figure in the Dutch Revolt against Spanish rule. Born around 1557 in Franche-Comté, Gérard was a devout Catholic and staunch supporter of Spain and the Catholic cause. He viewed William as a heretic and a rebel for leading the Protestant rebellion against the Catholic Habsburg monarchy. In 1584, Gérard carried out the assassination by shooting William in his residence in Delft, ending the life of one of the most important leaders of the Dutch struggle for independence. Gérard was captured immediately, tortured, and executed for his crime. Despite this, some considered him a martyr for the Catholic cause, while others saw him as a villain. Roman Catholic churches were seized and sacked. Works of art and liturgical objects, which were expressions of "Popish idolatry," were destroyed in the iconoclastic fury. Monasteries were demolished, and the possessions of monks and nuns were confiscated. Dutch Catholicism fell into disarray and not until the end of the sixteenth century did it begin its recovery. Burghers of Catholic faith became second-class inhabitants, and everyone who had an official duty in the municipality or had some ambition to get one, had to convert to the Reformed faith.

Vermeer's parents, Reijnier Digna, did not adhere to strict religious practices and were likely part of a group in Dutch society known as liefhebbers.Liefhebbers were individuals who, for various reasons, did not fully conform to the requirements of formal religious membership. They may have had a dislike for religious discipline, or they might not have officially registered as members of a specific religious faith. In the case of Vermeer's parents, it appears that while they were not actively involved in the Reformed faith, they did not fully conform to its strict requirements. This allowed them a degree of freedom in their religious practices and likely contributed to Vermeer's upbringing in a household with more relaxed religious beliefs.

When Vermeer's parents married in 1615, the suppression of the Catholic faith in Delft was complete. However, although national decrees prohibited Catholics the right to serve public office, many areas of the Netherlands remained solidly Roman Catholic. Despite the hostility, Dutch Catholics continued to worship and educate throughout the seventeenth century. In large cities like Amsterdam, Haarlem and Utrecht, commercial concerns dampened repeated calls for anti-Catholic laws. However, although intolerance existed in the United Provinces, while Dutch Catholics enjoyed remarkable freedoms compared with religious minorities elsewhere in early modern Europe. Toleration had its limits, but even though the penal laws against Catholics were occasionally enforced, and Catholics were vulnerable to extortion, things could have been worse.

Vosmeer was officially appointed to head the Catholic community in the Dutch Republic as vicar apostolic by Pope Clement VIII in Rome on 22 September, 1602, on which occasion he was also made titular archbishop of Philippi (since it was impossible to make him archbishop of Utrecht).

A new generation of priests and clergymen adapted themselves to the hostile climate and began working in clandestine to reorganize Catholic parishes and ensure regular Holy Masses for the faithful. Some of them traveled to Rome to petition Pope Clement VIII to send the Jesuits to Holland. In 1592, the first Jesuit mission was founded in Delft by Cornelis Jacobsz. Duyst. Another inhabitant of Delft, the secular priest Sasbout Vosmeer (fig. 2), who had done missionary work in Delft and its surrounding rural areas, was appointed by Clement VIII as Vicar Apostolic. He led the so-called Missio Hollandica ("Hollandse Zending") in the Netherlands.

Vosmeer was banished by the government in 1613 for his ceaseless efforts to fully re-establish the Catholic Church in Holland. He went to Cologne and continued his work with the foundation of a Collegium Alticollense to educate priests for the diocese Utrecht. Vosmeer died in Cologne in 1614. His obsessive goal to re-establish Catholic faith in Holland can be gauged by one of his most singular actions. Some time after the public execution of Balthasar Gerards, the fanatic assassin of Prince William I of Orange, pater patriae of the young Dutch Republic, Vosmeer acquired the head of Gerards, preserved "in sterk water" (in fact: in water with high quantity of pure alcohol). He brought the head to Rome for the canonization of Gerards, but—fortunately—without success.

Under the direction of Phillip Rovenius, the second apostolic vicar of the Netherlands, the presence of the number of Catholic and secular priests dramatically increased. Catholic priests generally preferred to serve in urban areas since the rural population remained staunchly hostile to Roman Catholicism. According to one report, of the 23,000 people who lived in Delft, 2,000 were of the Catholic faith in 1622, while three decades after, this number grew to about 5,000.

In Delft, an understanding was reached whereby if the Catholics remained discreet in their practices and continued to pay bribes to the local sheriffs, they were allowed to live in relative freedom.

Catholicism in Delft

The Jesuits, who had established their first Dutch mission in 1592, moved to a permanent location in Delft in 1612. In 1650, Catholic inhabitants of Delft had the "choice" between three schuilkerken (hidden churches): two (dated from 1630–1650) in the Bagijnhof (see in the following section) at the Oude Delft canal, dedicated to Saint Hippolytus and Saint Ursula and attended by secular priests, and the third one, established 1617 in an old warehouse at Oude Langendijk, dedicated to Saint Josef and supervised by the Jesuits.

Due to the increasing population, the hidden church at Oude Langendijk was expanded around 1835 and was rebuilt to a so-called waterstaatskerk.A waterstaatskerk was a type of church in the Netherlands, constructed with government approval and often partially funded by the state. The name derives from the Rijkswaterstaat, the governmental department responsible for public works and water management, which oversaw their construction. These churches were typically built in the 19th century and were associated with the Catholic Church after the Napoleonic Wars, when religious tolerance was reintroduced in the Netherlands. For this reason the house where Vermeer and his family had lived nearly three hundred years earlier, had to be demolished.

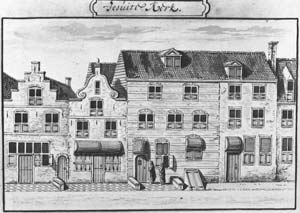

According to the research of John Michael Montias, by 1686, the Papist Corner included 15 houses in all. A schuilkerk, run by the Jesuits, was right next door to Maria Thins' house. In an early eighteenth-century drawing by Abraham Rademaker (1677–1735) (fig. 3), two women are shown entering the hidden church, and scholars believe the house of Maria Thins is either the one on the far right that extends off the drawing or another one further to the right that cannot be seen.

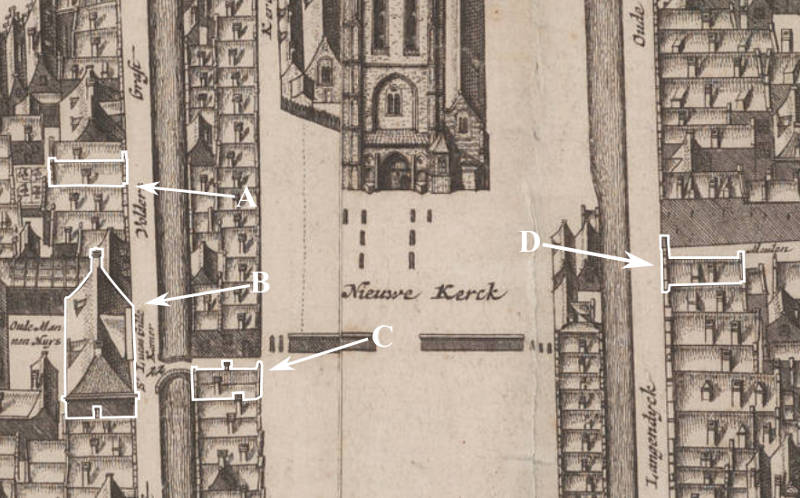

Vermeer and his wife, Catharina Bolnes, eventually moved to Oude Langendijk before 1660 from Mechelen, a large tavern on the Markt (Market Square) rented by his father where Vermeer and his family lived after leaving the Flying Fox. Given Vermeer's presumed but unproven conversion to Catholicism, it would have been natural for him to settle in the Papenhoek (Papists' Corner). The inn Mechelen, in the shadow of the New Church, frequented chiefly by Protestants, was not a good place to bring up children in the Catholic faith.

A. Flying Fox (Vermeer's presumed birthplace and inn of his father)

B. The Delft Guild of St. Luke (professional organization of artists and artisans)

C. Mechelen (a large tavern on the Market Square rented by his father where Vermeer and his family lived after the Flying Fox

D. Groot Serpent (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

E. Trapmolen (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

In Delft, many Catholic families were prosperous and lived close to each other.The Papenhoek was not a true Catholic ghetto, but rather more of a neighborhood since no one was forced to live there. The Catholic faith was scorned by diehard Protestants as "Romish superstition." However, the most skilled craftsmen who had migrated from the South seemed to stick with their old religion. Although Catholics were not actively repressed in the Netherlands in general, they were not altogether free to act as they wished.

In the Catholic part of the city, many homes were owned by affluent Catholics who either gave them to Jesuits or rented them out for their religious order's benefit. Because public Catholic worship was prohibited, the Jesuits conducted Mass in a hidden church concealed behind two homes' facades, accommodating up to seven hundred attendees. This row of houses also housed a Catholic girls' boarding school where well-off girls were taught reading, writing, French, and handiwork. Residents practiced their faith discreetly, both individually and collectively, reflecting the era's blurred lines between private and public life. The community was close-knit, characterized by mutual duties, strong social oversight, and mutual support. It's likely that Vermeer's neighbors played a role in his December 1675 funeral, adhering to seventeenth-century customs.Pieter Roelofs and Gregor Weber, VERMEER (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023), 45.

Abraham Rademaker

c. 1670

Brush and gray ink, 13.2 x 20.2 cm.

Gemeentearchief, Delft

Adherents to the old faith suffered mainly official discrimination. They were denied access to all municipal functions. They could no longer become burgomasters, aldermen, or sheriffs but they retained influence in some of the guilds, including the Guild of Saint Luke. Vermeer himself was elected two times to head this guild.

While the municipal authorities, under the pressure of Reformed ministers, frequently issued regulations that made life difficult for the Catholics, their repressive policies were rendered ineffective due to political and economic considerations. Many Catholics were prominent in business and industry, and therefore vital for the prosperity of the town. Many of the most successful faienciers, who employed a sizable part of the community, were Catholics. In any case, there were simply too many Catholics left in Delft—about a quarter of Delft's population—to ban the exercise of their religion altogether. The city's magistrates complained in January I643:

Despite the edicts against the adherents of the Pope and their allies, which have been many times reissued, we find that, instead of obeying they have increased in boldness and not only continue their gatherings but also in great numbers come to other people [i.e., to proselytize], as if there were no edicts, and have bought house after house, which they have made their own for this purpose, which have entrances in the dividing walls such that they cannot be disrupted successfully.