Fame

By the time he had painted the so-called "pearl pictures," Vermeer's name must have been well known, at least to a circle of discerning Dutch art collectors who lived in and near Delft. Balthasar de Monconys (1611–1665), a well-connected French traveler, diplomat, physicist, and magistrate, visited Delft during the summer of 1663. He came initially as a tourist, evidently unaware of Vermeer's presence. Soon afterward, he returned to Delft visiting Vermeer at his studio and wrote the following account in his diary journal, published in 1665, the year of his death:

In Delft I saw the painter Verme(e)r who did not have any of his works: but we did see one at a baker's, for which six hundred livres had been paid, although it contained but a single figure, for which six pistoles, approximately 600 guilders) would have been too high a price.

It is unlikely that de Monconys made the trip to Vermeer's studio because the artist's fame had spread to France. Instead, the well-introduced traveling Frenchman had almost certainly entertained some sort of relationship with Constantijn Huygens, diplomat, poet, musician, and promoter of Dutch art, who lived in nearby Hague and would not have hesitated to rectify the Frenchman's oversight and direct him to the Delft artist's studio. De Monconys, who was a devout Catholic brought up in Lyon by the Jesuits, had an interest in the Jesuit missions in infidel territory and may have also been interested in making contact with the Jesuit community in Delft.

Unfortunately, de Monconys made no mention of the style or quality of Vermeer's painting—it appears he judged them soley on the basis of the number of hours required to do the work. De Monconys was probably even more shocked when he found that Frans van Mieris (1635–1681) wanted no fewer than twelve hundred livres for a more elaborate figure piece of a sick lady and a quack doctor. The Frenchman continued to visit the studios of other important Dutch artists.

& Privé, & Lieutenant Criminel au Siège Presidial de Lyon

Balthasar de Monconys

2 vols., Lyon, 1665–1666. page 148–149

If the price quoted by the baker is to be believed, Vermeer's paintings were, in fact, rather expensive. Even so, the artist's fame did not spread far outside Delft. The most probable explanation is that his paintings were in the hands of only a few select collectors, principally, Pieter van Ruijven. Vermeer's reputation might have spread in wider circles and his name might have been better remembered after his death had there been more collectors eager to trumpet his fame.

The baker mentioned by de Monconys is almost certainly Hendrick Ariaensz. van Buyten (1632–1701), a prominent citizen of Delft and master baker (boulanger), headman of the Bakers' Guild in 1668. He earned more than 2,855 guilders a year, a considerable sum when a guilder a day was a very good salary. One year after the artist's death in January 1676, a month and a half after Vermeer's death, Van Buyten received two pictures from Vermeer's wife, Catharina, as a security against a very substantial debt of more than 617 guilders and 6 stuivers (such a sum was roughly the equivalent of two to three years' worth of bread or the price paid for a small house in the Netherlands in those times). One of the works was described as "two personages one of which sits and writes a letter," probably Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid, and the other, "a personage playing on a zither," probably the London Guitar Player. After the baker's death in 1701, the former work was encountered "in the vestibule" of his home as "a large painting by Vermeer." In another room hung "two little pieces by Vermeer." The paintings would be returned to Catharina if she paid all her debts. Van Buyten demonstrated considerable generosity to Vermeer's widow in that she was allowed to repay the main part of the debt in 12 years at a rate of fifty guilders per year without interest.

Vermeer paintings were also in the private art collections of Johannes de Renialme, Cornelis van Assendelft, Cornelis de Helt, and Gerard van Berckel.

Gregor Weber has recently suggested that some of Vermeer's mid-career works, influenced by Jesuit theological-moralistic literature, reflect the strong influence of the Jesuit order on Vermeer, given their proximity and potential financial ties.Gregor J.M. Weber, Johannes Vermeer: Faith, Light and Reflection (Rotterdam: nai010 Publishers, 2023).

The Geographer and The Astronomer

Aside from two lost works, a lost self portrait and a man "washing his hands," only two paintings have survived by Vermeer that feature exclusively men, The Geographer and The Astronomer. Both pictures reflect current fashions in paintings of scholars in their studios and are considered by most art historians as a pendant.

In the construction of the Geographer, Vermeer was most likely guided by someone familiar with geography and navigation, demonstrated by the sophisticated description of the scientific instruments. Moreover, none of these expensive instruments were mentioned in the inventory of movable goods made after the artist's death in 1675. In Delft, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek was well known for his discoveries with the microscope but he was also described as skilled in navigation, astronomy, mathematics, philosophy, and natural sciences. He was born in Delft in 1632, the same year as Vermeer. Some experts believe that it was Van Leeuwenhoek who posed for both works and perhaps commissioned them as well. A portrait by the Delft painter Jan Verkolje shows the scientist when he was fifty-four years old, some eighteen years after Vermeer's painting. Whether or not the scientist's features resemble those of Vermeer's long-haired scholar is debatable.

Johannes Vermeer

1668

Oil on canvas, 50 x 45 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

However, Vermeer's Astronomer should not be understood as a portrayal of modern science, a painterly expression of the Copernican revolution in astronomy. In Vermeer's time, all natural phenomena, including the heavens, had an inexorable moral significance which implied the Divine Creator who had created nothing without a reason. The idea of science as a coherent enterprise as we know it today was just emerging.

Historian Klaas van Berkel conjectures that The Astronomer represents a combination of ancient wisdom (see the painting of Moses on the wall to the right) and modern science, represented by the various scientific instruments on the table.

In the past, some scholars have refused the idea that the painting represents an astronomer citing the evident lack of a telescope and the fact that the figure is working in a closed environment during the daytime. Perhaps, they surmised, he was devoting himself to the older, non-empirical science of astrology, in other words, he might have been drawing up a horoscope or in some way attempting to divine the order of the natural world through the movements of the celestial bodies. In those times there was no clear distinction between astronomy and astrology, while there was a strong division between astronomy/astrology and physics. Famed astronomers such as Johannes Kepler and Tycho Brahe, who were dedicated empiricists, were still practicing astrologists. Kepler believed in astrology convinced that planetary configurations physically and really affected humans as well as the weather on earth. He advocated that a definite relationship between heavenly phenomena and earthly events could be established.

Even though the open book of the Astronomer has been painted with a few dabs of applied paint, the historian James A. Welu was able to identify the book as the 1621 second edition of a tract by Adriaan Metius, Institutiones Astronomicae et Geographicae. It is opened to Book III, where "inspiration from God" is recommended for astronomical research along with knowledge of geometry and the aid of mechanical instruments.

Learning and Intellectual Scope

Art historians have long debated the artist's learning and the intellectual scope of his art. We know that he possessed 25 books "of all kinds," cited in the inventory of movable goods of the artist's estate, but we know neither their titles nor authors. They may have been religious or philosophical tracts or simply music books, manuals for painting, or perspective.

In recent years, various authors have endeavored to link Vermeer's measured art and his concerns with optics to the intellectual currents active in the Netherlands and Europe. Vermeer's "classicism" and his apparent rationalism have been associated with French art and philosophy by some art historians. Robert Huerta promoted the Delft artist to the role of the natural philosopher (natural philosophy was a term applied to the study of nature and the physical universe that was dominant before the development of modern science) and holds that common intellectual threads link his art to the philosophy of Plato.Robert D. Huerta, Vermeer And Plato: Painting The Ideal (Bucknell University Press, 2005). He used painting, in Huerta's words, to make a "world of his own creation, a world-encompassing classical and Christian, temporal, and eternal, real, and ideal."

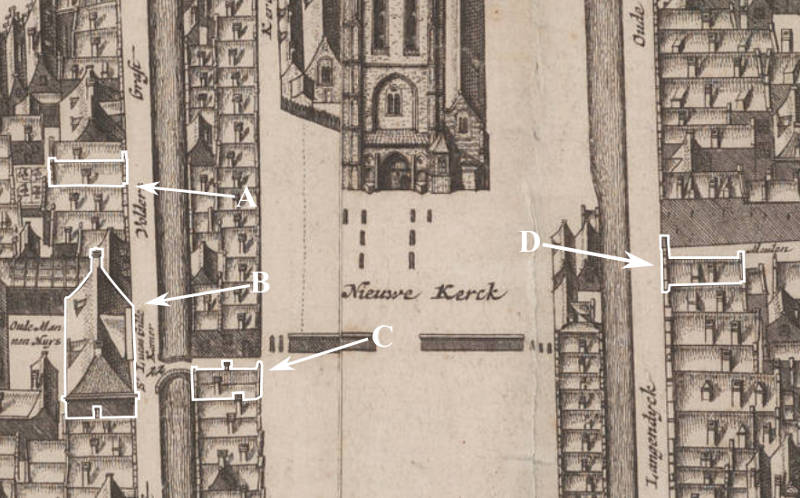

A. Flying Fox (Vermeer's presumed birthplace and inn of his father)

B. The Delft Guild of St. Luke (professional organization of artists and artisans)

C. Mechelen (a large tavern on the Market Square rented by his father where Vermeer and his family lived after the Flying Fox

D. Groot Serpent (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

E. Trapmolen (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

On the other hand, according to Walter Liedtke, "the allusions made in several of his pictures suggest that [Vermeer] was not unread, at least in fields directly relevant to the matters at hand. And Vermeer probably had a few well-schooled acquaintances, in particular Huygens (who corresponded with Descartes and Mersenne). But there seems no reason to rank Vermeer with learned artists like Rubens and Poussin; he probably had some secondhand notions of contemporary science and philosophy, but they appear to have had little bearing on his style. The very qualities that comprise Vermeer's so-called classicism—a term which has nothing to do with other aspects of his work—had been favored in Delft and The Hague for decades: perspective, proportion, restrained action, and expression, a sense of order, and in some cases measure and harmony." In any case, since books were still expensive, the number possessed by Vermeer is substantial for a family of medium economic means."Walter Liedtke, ed., exh. cat. Vermeer and the Delft School (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 165–166.

Loss

In 1667, the Vermeer family mourned the death of a male infant child, buried in the family grave in the Oude Kerk purchased six years earlier by Maria Thins. In the same year, Vermeer was entrusted by Maria Thins to collect debts owed to her and reinvest the proceeds or pay off obligations. In 1668, Maria Thins empowered Vermeer to collect funds owed to her children Willem and Catharina from funds left by their great aunt. In the next year, Vermeer's mother put up the family inn Mechelen for auction at 5,000 guilders but was unable to sell it.Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2002), 95. She then rented it to Leendert van Ackerdijck for 190 guilders a year, which let her only 65 guilders after a year's mortgage payment. Vermeer and his wife mourned another child in July 1669, Gertruy and her husband made out a new will evidently due to her failing health. Gertruy signed the will "Geertruit Vormeer" with a trembling hand. Two days later, on February 13, Vermeer's mother was buried in the Nieuwe Kerk and Gertruy died on May 2 of the same year.

"Curiosities"

Other than that of the Frenchman de Monconys who had visited Vermeer's studio in 1663, the only written eyewitness account of Vermeer's paintings was penned by Pieter Teding van Berckhout (1643–1713), a young scion of a landed gentry family. In his diary, May 14, 1669, he wrote:

"Le 14 mat 1669 : je fus leve assez matin, parlois a mon cousin Brasser de la Brile, et men fus promene a

Delft avec unjacht ou estoit Monsieur de Zuylechem van der Horts et [Monsieur de] Nieuivpoort. Lstant arrive

ie vis un excellent peijntre nomme Vermeer, qui me montra quelques curiosites de sa main." ["14 May 1669: I

got up quite early, spoke with my cousin Brasser de la Brile, and went to visit Delft in a yacht with Mr.

Zuylechem van der Horts and [Mr.] Nieuwpoort. When I arrived I saw an excellent painter named Vermeer,

who showed me some curiosities he had executed himself."]"

Van Berckhout had arrived in Delft accompanied by Constantijn Huygens and his friends—member of parliament Ewout van der Horst and ambassador Willem Nieupoort. Huygens was an artistic authority in his own day, maintaining contacts with the famous Flemish painters Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck and recording in his own diary some remarkably insightful comments about the art of, among others, Rembrandt van Rijn. However, Huygens did not visit the artist's studio.

Van Berckhout must have been deeply impressed by the work he saw because he returned for another visit less than a month later. On June 11, he noted:

"I went to see a celebrated painter named Vermeer who showed me some examples of his art, the most extraordinary and most curious aspect of which consists in the perspective."

On 1670, Vermeer was again appointed headsman of the Delft Guild of Saint Luke together with Louis Elsevier. It remains uncertain if Vermeer collaborated with fellow Guild members or engaged in artistic disciplines other than painting. Yet, artworks by other Delft painters have surfaced. in his compositons; notably a landscape by Pieter van Asch in the backdrop of The Guitar Player. Later, in A Lady Standing at a Virginal, he adapted an artwork by Van Groenewegen, showcasing it on the virginal's lid. Vermeer often adorned his depicted interiors with Delft tile wainscoting. Additionally, he depicted jugs in some of his works, including a notable white Delft jug. Nonetheless, many of the most important fine artists of the Guild had left Delft, evidently to seek more promising markets.

Earnings

Until the 1670s, Vermeer and his ever-growing family may have lived a relatively comfortable life. Montias estimated that Vermeer's income could have ranged from about 850 to 1,500 guilders a year (from two or three elaborately painted works and a few smaller ones) but that he probably never made any money on the heavily mortgaged Mechelen which he inherited from his mother and sister. On the other hand, he could count on Maria Thins's unflinching financial backing and rent-free accommodation she provided for his growing family.

Throughout their lives, Vermeer and his wife, Catharina, unexpectedly inherited from various family members who either didn't marry or had no offspring.

In 1651, Jan Willemsz Thins, the brother of Vermeer's mother-in-law, Maria Thins passed away, leaving his inheritance to his sisters, Maria and Cornelia. By 1661, with Cornelia's death, Maria became the sole heir of the Thins family, enjoying an annual income of 1,500 guilders, sufficient for a decent lifestyle. A craftsman's family could live on just 500 guilders annually. Until the early 1670s, Maria and her son-in-law, Vermeer, jointly supported their expanding family. At his peak, Vermeer, earning 850-1,500 guilders per picture, painted meticulously crafted pieces every few months, ensuring the family's comfort. However, the luxury goods market would wane during economic downturns caused by wars or other events.

On Johannes Vermeer's side of the family, there were smaller expectations. When his mother died in February 1670, he shared the inheritance with his sister Gertruy and brother-in-law Anthony. His part of the legacy was the inn Mechelen, which had been rented out for the past year. But the amount of the rent in 1670 was scarcely more than the interest on the mortgage with which the inn was encumbered. In a will drawn up two days before Digna Baltens was buried, Gertruy, Vermeer's sister, who was childless, made a bequest of 400 guilders to her brother. Vermeer in fact received only 148 guilders when Gertruy died soon afterward, in May 1670, probably because he had to pay some debts on Mechelen before he could get the money.Montias, John Michael. "Chronicle of a Delft Family," in Vermeer, edited by Albert Blankert, Gilles Aillaud, and John Michael Montias, (Woodstock and New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2007) 96.

In 1669, Pieter Teding van Berkhout, a young enthusiast of painting connected to notable Dutch families, documented his encounters with various painters in his journal. Six years after a visit from Monconys, Pieter met Vermeer in Delft. He described Vermeer as an "excellent painter" and noted that during his visit, Vermeer showed him some of his pictures. This was after Pieter's interactions with other renowned artists like Cornelius Bishop, Caspar Netcher, and Gerard Dou.

Here is how Van Berkhout describes his first visit to Vermeer's studio in his journal, which he wrote in French:

"Le 14 mat 1669: je fus leve assez matin, parlois a mon cousin Brasser de la Brile, et men fus promene a Delft avec unjacht ou estoit Monsieur de Zuylechem van der Horts et [Monsieur de] Nieuivpoort. Étant arrivé, je vis un excellent peijntre nomme Vermeer, qui me montra quelques curiosites de sa main." ["14 May 1669: I got up quite early, spoke with my cousin Brasser de la Brile, and went to visit Delft in a yacht with Mr. Zuylechem van der Horts and [Mr.] Nieuwpoort. When I arrived I saw an excellent painter named Vermeer, who showed me some curiosities he had executed himself."]

However, by 1672, the French invasion impacted the Netherlands adversely, all but obliterating the art market. Vermeer's sales plummeted, and he faced debts, leading to his eventual demise in despair.Albert Blankert, in Vermeer, ed. Albert Blankert, John Michael Montias, and Gilles Ainaud (New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2007), 30.

Vermeer Biographies

- John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., "Vermeer of Delft: His Life and his Artistry," in Johannes Vermeer, edited by Albert Blankert, Ben Broos, and Jørgen Wadum, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995, 15–29.

- Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft, New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2001.

- Walter Liedtke, "Johannes Vermeer 1632–1675," in Vermeer: The Complete Catalogue, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008.

- Schütz, Karl. Vermeer: The Complete Works. Cologne: TASCHEN, 2021.

- Montias, John Michael. "Chronicle of a Delft Family." In Vermeer, edited by Albert Blankert, Gilles Aillaud, and John Michael Montias, 96. Woodstock and New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2007, 15–72.

- Roelofs, Pieter, and Gregor Weber. VERMEER. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023.

- Weber, Gregor J.M. Johannes Vermeer: Faith, Light and Reflection. Rotterdam: nai010 Publishers, 2023.