Forms of the Shawm

Many different configurations of the shawm exist. One special form, probably originated from the early sixteenth century, is the windcap shawm, known in Germany and the Low Countries as Rauschpfeife or "russ pfeiff" (Dutch: rietpyp, rytpyp). The name is thought to be derived from the Old German "rusche" meaning "reed" or "cane." In Praetorius' drawing we find a small detachable windcap fitted over the reed of the normal treble shawm.

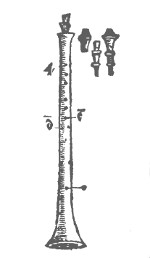

The windcap shawm is a historical woodwind instrument, related to the shawm family and a precursor to the modern oboe. Characterized by a windcap covering its double reed, it produces a controlled, mellow sound, contrasting with the louder tone of open-reed shawms. Primarily used during the medieval and Renaissance periods, it came in various sizes for different pitch ranges. The playing technique involves breath pressure and finger holes for pitch control. The windcap shawm was utilized in both secular and sacred music and played in ensemble settings. While its use declined with the development of newer woodwind instruments, there's a modern resurgence in interest for historical music and instruments, including the windcap shawm. The instrument has a conical bore without a bell. The double-reed resides inside the windcap (fig. 1). This design produces a loud, screaming sound, full of overtones. Therefore, it is also called Schreyerpfeife or Schryari by Praetorius (from German: "schreien" = "to scream") (fig. 3). The player blows into a slot at the top of the windcap in order to produce sound. The instrument has eight medium-sized fingerholes whereby the eighth hole is fingered with the left thumb. The larger sizes have a little-finger-key with a fontanelle for the lowest note as well as upward extension keys operated by the index finger for the upper range.

In the sixteenth century, the word "rauschpfeife" was sometimes used to denote woodwind instruments in general (fig. 3). A purchase order for musical instruments placed by the Nuremberg town council in 1538 mentioned "a large Bommart and associated Rauschpfeiffen," but the delivery included recorders, cornetts, shawms, and other instruments, but none specifically termed "rauschpfeifen."

Appart from the five shawm-players in Hans Burgkmair's woodcuts for the Triumph of Maximilian I (fig. 4) there are also five players of "Rauschpfeiffen," as they are referred to in the accompanying contemporary text.

Another form, the "Hirtenschalmei" (shepherd's shawm) is often mentioned in medieval French literature and poetry and appeared frequently in paintings usually played by shepherds or rustic figures.

Similar to the rauschpfeife, the tone of the hirtenschalmei is produced by a capped double-reed and sounds rich and buzzy. The main bore is cylindrical and ends in a large flared bell.

Claude Lorrain

1642

Oil on canvas, 97 x 131 cm. Staatliche Museen, Berlin

A shepherd couple is placed in the foreground. The woman is seated on a rock and is listening to the shepherd playing a shawm.

Jan Baptist Wolfaerts

1646

Oil on canvas, 75x 67.5 cm.

Collection

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The only surviving instrument of this kind was unexpectedly discovered during salvage operations in 1980 on King Henry VIII's famous warship, the "Mary Rose," which had sunk in the English Channel in 1545. This instrument may also have been a "dulzaina," described by Johannes Tinctoris as a rather low volume reed instrument of limited range, suitable for indoor music. Reconstructions of the hirtenschalmei (fig. 5) are made after the "Mary Rose" instrument, in soprano, alto and tenor size.To the musical instruments found on the "Mary Rose" see Frances Palmer, "Musical instruments from the Mary Rose. A report on work in progress." Early Music 11, 1 (January 1983) 53–60.

Parallel to the gradual development of the oboe (see expert-box) during the second half of the seventeenth century, a distinct type appeared described by contemporary sources as "Deutsche Schalmey." This instrument is a curious combination of the shawm and the new French oboe which had preceded general adoption of oboes by German military regiments, hence its name. It was also well-known in the Netherlands as "Duitse schalmei" (or "velt-Schelmey," as it was called by seventeenth-century instrument makers in Amsterdam). Recent interpretation denote the Deutsche Schalmey as a survival of the earliest form of the prototypical oboe developed in France by Hotteterre, which seemed to have found a musical niche in the German-speaking area, especially in military Hautboisten-Banden beginning in the 1640s. Evidently, the Schalmey and oboe co-existed rather competed. This instrument was slender and graceful in build and was made of two sections, with thinner walls, a narrow and often roughly turned bore, and smaller finger-holes. Two sizes, treble and tenor, were made, each provided with a fontanelle, although only in the tenor did this cover a key. The tone was sweeter and the playing-technique demanded a less specialized embouchure than the oboe. The instruments could either have a pirouette, or be blown without one, like the oboe.

Click here for period rauschpfeife music:

Nachtanz, a dance tune by Tielman Susato. The melody is played by the rauschpfeife (probably an alto).

Performed by early music ensemble Musica Antiqua, Iowa State University.

Click here for period hirtenschalmei music:

Ain niederlandisch runden Danz,

(with themes by Tielman Susato),

beginning with lute and percussion, and with hirtenschalmei-trio at 1:46.

Performed by early music ensemble Musica Antiqua, Iowa State University.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century the Schalmey disappeared, probably because it was "difficult to blow, and struck the ear unpleasantly in the higher register" as a contemporary notice mentions. However, it remained in use in rural areas for some time longer.

Although very popular in its time, the shawm doesn't appear as often in Dutch painting as the fiddle, bagpipe or hurdy-gurdy, perhaps because it was used mainly by municipal pipers who had not been as an attracive motif as the popular rustic, music making scenes. Shawms (at least their lower parts with the picturesque fontanelle) are found in Vanitas-still lifes (fig. 6) or in scenes of the Classical mythology where they may refer to the divine meaning of their ancient predecessors, the Greek aulos (see The Bagpipe). The Greek poet Pindar (518 B.C.–c. 438 B.C.) tells us in his twelfth Pythian Ode about the invention of the "shawm" (i.e. aulos) by the goddess Athena, which became a divine instrument. Ancient depictions of the Nine Muses, the divine companions of the god Apollon, show the muse Euterpe with a single or double-pipe.

Evert Collier

1663

Oil on panel, 56.5 x 70 cm.

National Museum of Western, Tokyo

The lower part of a shawm with an accurately depicted fontanelle and the flared bell features like a highlight between the two dark globes in the background.

Sophocles (Ant. 65) tells us, that the muses love the "shawm" (aulos), and Euripides calls it the "servant of the muses" (Elek. 717).See Max Wegener, Das Musikleben der Griechen (Berlin, 1949), 11ff. and Martin L. West, Ancient Greek Music (Oxford, 1994), 81ff., esp. 85. To the practice of ancient Greek music see the very informative website Ancient Greek Music with various sound-examples on reconstructed instruments (aulos and cithara). Painters of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries took up these highly regarded ancient references in their mythological scenes to the delight of the potent upper class who favored sophisticated inconographical references.

Regarding the every-day scenes, it is again Jan Steen (c. 1626–1679) who depicted shawm-players several times. One particular rendition figures prominently in the foreground of his humorous The Dancing Lesson (fig. 7), where a girl is playing a shawm while the other children are trying to get a kitten to danceBruce Haynes, "Lully and the Rise of the Oboe as Seen in Works of Art," Early Music, Volume XVI, Issue 3, August 1988, Pages 324–338. In Steen's well-known Village Wedding (1653) (fig. 8) there are two shawm-players (the left-hand player probably holds a sopranino), leaning out of the right side of the window they blow full strength on their instruments heralding the bride's arrival. Perhaps these players are members of the municipal pipers since the larger instrument is decorated with a banner, probably with the town's arms on it.

Jan Steen

1660s

Oil on panel, 68.5 x 59 cm.

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

Jan Steen

1653

Oil on vanvas, 64 x 81 cm.

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

The still life in the foreground of Caesar van Everdingen's (1616/17–1678) Four Muses (fig. 9) shows eleven lifelike musical instruments, arranged in an artful composition. Among them are two shawms: the one arising with its lower part somewhat unrealistic between a vielle and a bass viol, with a portative organ at the side; the other one, made of dark wood and elaborately carved, appears, half covered from the vielle, at the lower left side, other instruments are a harp, a recorder, a tenor viol, a tambourine, a trombone and a trumpet (behind the portative organ).

Caesar van Everdingen

c. 1650

Oil on canvas, 340 x 230 cm.

Collection Huis ten Bosch, The Hague

Although by 1700 most provincial waits were replacing their shawms with the new oboes and bassoons, shawms remained in use in some places longer than elsewhere, particularly north of the Alps. They still featured in the Stadtpfeiferei to the end of the eighteenth century. Goethe (1749–1832) noted the "Schalmei" and "Pommer" in his Dichtung und Wahrheit (1811–1833), in an account of a procession of the Nuremberg Stadtpfeifer on its way to the Pfeifergericht, an annual confirmation of trading privileges. Two instruments, used in this procession and made by members of the renowned Denner-family of woodwind instruments makers (see The Dulcian), have survived and are housed in the Frankfurt Historisches Museum.

New interest concerning the historical evidence of the shawm as the predecessor of the oboe came with the early music movement in the 1970s and led some makers and players to become authoritative specialists.

Structure and Playing Technique of the Shawm

Shawms were made of various hardwoods, often maple. They have a conical bore expanding into a bell and are usually made of one piece, except the larger instruments which consist of several sections fitted together. These instruments have seven finger-holes at the front. At the larger instruments the sound is let through the lowest hole which is closed by a key protected by a slide-on wooden barrel, the fontanelle, perforated by small holes, arranged in ornamental patterns. Below the lowest finger-hole there are several vent-holes to correct the effect of the acoustically overlong bell section, which ensures tonal stability. Shawms were usually played with a pirouette (English: "fliew") apart from the lower ones.

The double reed, made of the species Arundo donax, was placed on a staple, which in turn was fitted into the pirouette in order to leave the upper part of the reed clear. The lower part of the staple was wound with thread and fitted into the neck of the shawm. The reeds were probably shorter and somewhat broader than those used today for the modern double-reed instruments (oboe, bassoon), although with a wider opening.

a) the staple, its lower part wound with thread

b) the pirouette

c) the reed, fitted into the pirouette

on the staple

Detail from the Adimari Cassone Wedding

Detail from the Adimari Cassone Weddingattrib. to Giovanni di Ser Giovanni, called 'lo Scheggia'

(1406–1486; younger brother of Masaccio). Galleria dell'Accademia Florence

The music ensemble consists of a trombone and three shawms. The third player from the left-side (looking to the viewer) is pausing to relieve his embouchure.

Click here for period shawm music:

Tielman Susato, La Morisque, from

Deerde musyck boexken "Dansereye" (1551).

Performed by the Renaissance band Piffaro.

The player's lips could rest against the top of the pirouette, supporting the embouchure against fatigue and allowing the reed to vibrate freely inside the mouth. The reed could be controlled directly by the lips allowing variable sound production. There are some depictions of a musical ensemble in which one shawm player is resting from the strain placed on the lips in performance.

The lowest tone of the various sizes of shawms from the Renaissance era are f1 for the sopranino, c1 for the soprano, f0 for the alto, c0 for the tenor and F for the bass. The great bass pommer had the lowest tone C—Praetorius uses the term "pommer," a corruption of the French word "bombarde," meaning a "cannon." The sound is rather an assault on the ears, too, which made it the favored instrument for large gatherings, both indoors and out. Like the recorders, largers shawms feature a fontanelle— a "pepper shaker" cover for the key mechanism that served both to protect the key and hide its asymmetry. The key itself is often referred to as a "swallow-tail," and its shape allowed the instrument to be played with the left or the right hand down, there being no standard method as there is today.The fingering on the larger instruments is problematic because of the large distance of the fingerholes. The lowest tones of the larger instruments are handled with a key (or up to 4 keys at the bass instruments).

Shawms overblow at first times into the octave, at second times into the twelfth, but usually they are overblown only once.

Shawms and pommers, together with cornetts, dulcians/curtals and trombones will always remain the regular instruments of many Renaissance wind ensembles like the Piffaro.

Shawn resources:

- Grove Music Online:

https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic - entry "Shawm": Anthony C. Baynes / Martin Kirnbauer

entry "Rauschpfeife": Barra R. Boydell

entry "Wind-cap [reed-cap] instruments": Barra R. Boydell - Anthony Baines, Woodwind Instruments and their History. London 1957.

- Bruce Haynes: "Lully and the rise of the oboe as seen in works of art," in: Early Music XVI, 1

(February 1988) 324–338.

The shawm on the web:

- Musica Antiqua, Iowa State University:

http://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/ - Medieval shawm

https://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/search/content/Medieval%20shawm - Renaissance shawm

https://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/search/content/Renaissance%20shawm - Hirtenschalmei

https://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/search/content/Hirtenschalmei - Der Sackpfeyffer zu Linden:

- Shawm

http://www.sackpfeyffer-zu-linden.de/shawm.html - Zurna

http://www.sackpfeyffer-zu-linden.de/zurna_en.html - Rauschpfeife

http://www.sackpfeyffer-zu-linden.de/rauschpfeiff.html - Wikipedia "Shawm"

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shawm