The Recorder in Vermeer's Painting

The recorder makes only one minor appearance in Vermeer's oeuvre, in the late Girl with a Flute (fig. 1), sometimes considered a pendant to the Girl with a Red Hat. Helen Hollis, formerly of the division of musical instruments at the Smithsonian Institute, observed that although the fipple mouthpiece is correctly indicated by the double highlight, the air hole below the mouthpiece is off-line (fig. 2). As seen in the recorder hanging on the wall in a painting by Judith Leyster (fig. 3), it should lie on an axis with the upper lip of the mouthpiece. The finger holes seen below the girl's hand are turned even further off this axis, although such a placement would be allowable if the recorder were composed of two sections.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1665–1670

Oil on panel, 20 x 17.8 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Scientific examination of the painting reveals that the finger which rests on the recorder was added, suggesting that the flute did not exist in the original composition. Without the added finger, the flute could not be held.

However accurate the representation of the instrument itself may be, no one has advanced a plausible idea of the iconographical meaning of the singular combination of the young girl's Chinese hat and the instrument. Indeed, there may have been no specific meaning intended, as the painting was meant only to be a tronie, a Dutch term used to describe a type of genre painting from the seventeenth century that focuses on depicting a person's facial expression or character rather than a formal portrait. Tronies often featured exaggerated or theatrical expressions and were a popular subject in Dutch Golden Age art.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1665–1670

Oil on panel, 20 x 17.8 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Judith Jansdr. Leyster

c. 1635

Oil on canvas, 62 x 73 cm.

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden

Classification

The recorder, as a woodwind instrument, belongs according to the Sachs-Hornbostel system to the group of "aerophones" which produce the sound by vibrating a column of air. The recorder is a member of the ancient family of internal duct flutes with a fixed windway formed by a wooden plug or "block"; hence the German name "Blockflöte."

History

The early ancestors of the recorder were most likely whistles used for signaling rather than true musical instruments. They can be traced back thousands of years, as evidenced by an instrument made from a sheep bone, which was found in England in a tomb from the Iron Age. The date and place of origin of the first European recorders remain unclear. Portrayals of wind instruments ("pipes"), which may be recorders, appear in medieval sculptures, carvings and paintings from the eleventh to the fourteenth century.

fig. 4

The Dordrecht-recorder

fig. 4

The Dordrecht-recorder c. late 14th century

One of the oldest surviving instruments, more or less complete, is the so-called "Dordrecht-Recorder" (late fourteenth century) which was found in a moat by a castle near Dordrecht. Another early recorder (c. fiourteenth century) made of plumwood was found in Göttingen (Germany).

During the fifteenth century, the recorder developed into the "Renaissance" form and was produced in various sizes for consorts shown by numerous surviving instruments. They have a wide conical bore, large finger-holes, and are capable of producing a loud sound but are weak in harmonics, with range limited to about an octave and a sixth. They are ideally suited to the performance of the polyphonic vocal and instrumental music of the fifteenth to the early seventeenth centuries, blending easily with each other in "whole" consorts (consorts of recorders) or contrasting well with other period instruments ("broken" consorts) or voices. The renaissance-recorder reached its zenith in the sixteenth century.

The first professional use of the recorder is documented towards 1500 when it emerged as one of the regular instruments of professional wind players, along with shawm, cornett, sackbut and sometimes trumpet. But it became increasingly popular among amateur musicians of all classes, including royal and noble households, which is evident from their inventories listing avast quantity sixty-seven wind instruments. The most celebrated inventory is that of Henry VIII of England which includes seventy-six recorders among a large number of other musical instruments. In about 1539, Henry VIII engaged five brothers of the famous Bassano family from Venice. This consort, expanded to six members in 1550, lasted intact until the amalgamation of the three court wind consorts into one group in 1630. Such a focus on the recorder seemed to have been an exception, but other noble courts, such as those in Exeter, Norwich or Chester, followed by acquiring "whole sets of recorders" from the London instrument makers. By the end of the sixteenth century, recorder-consorts with members were present in all London theatres.

Venice was a major centre of wind playing in the early sixteenth century. The "pifferi" (pipers) of the Doge played recorders as well as other instruments like cornetts, trumpets or shawms during the processions of the Scuola di San Marco, some of whom, later worked at the English Court. The pifferi worked closely together with the wind makers (one of them was Jacomo Bassano from the famous family) and acted as their agents.

With the change of the musical taste in the late sixteenth and seventeenth century into a more delicate, refined one, the renaissance recorder with its somewhat louder, robust sound had to be developed to meet the demands of the emerging styles of instrumental music. Instrument makers of the seventeenth century did not manage to establish a real tradition of recorder making, so it seems that they had worked independently of each other in different parts of Europe. That can perhaps justify their recorders as "transitional instruments" or "early baroque recorders" (see Eva LegêneEva Legêne, "The Early Baroque Recorder: 'Whose lovely, magically sweet, soulful sound can move hearts of stone,'" in The Recorder in the Seventeenth Century: Proceedings of the International Recorder Symposium in Utrecht 1993, edited by David Lasocki, 105-126 (Utrecht: STIMU Foundation for Historical Performance Practice, 1995).). They were characterized by an extended upper range, sometimes with ornamental rings at the foot and above the labium, longer windways and "wave profile" tuning, together with a softer, refined sound.

During the late seventeenth, century the recorder was completely redesigned for use as a solo instrument. Where previously made in one or two pieces it was now made in three allowing a more accurate boring. It got a more pronounced taper and had a fully chromatic range of two octaves up to two octaves and a fifth. It was voiced to produce an intense, reedy and penetrating sound of great carrying power and expressivity. Many splendid instruments (fig. 5) have survived until today in a playing condition.

In this form the recorder was best suited for performing chamber music and even solo concerti and survived as a highly esteemed instrument both for professional and amateur players until the late eighteenth century (as an amateur instrument some way into the early nineteenth century). Then it was temporarily and briefly superseded by the tranverse flute for the larger orchestras.

In the Baroque period, almost all professional recorder players had to earn their living from playing several instruments and were primarily oboists or string players, occasionally concentrating on more unusual instruments. Some also composed. The most famous player of the seventeenth century was certainly Jacob van Eyck, the blind composer of Der fluyten lust-hof (Amsterdam, 1646–1649), the largest collection ever published of music for a solo wind instrument. This collection, first published in 1646, is considered one of the most significant works of Dutch baroque music. It consists of over 140 melodies and variations for solo soprano recorder. Each piece is accompanied by a table of fingerings, making it accessible to both amateur and professional recorder players.

Van Eyck was also engaged by the municipals of Utrecht to play the recorder in the garden surrounding the Janskerk; his boven-menschte (superhuman) performance there is praised in a poem by Regnerus Opperveldt (1640). He was also the most outstanding carillon player of his time and became director of the carillons in Utrecht.

Apart from the professional playing, the late-baroque recorder was one of the most popular amateur instruments in all European countries, played in all classes, even in the aristocracy. Many amateurs were keen on emulating the professionals and required large quantities of the suitable music. Songs, and even whole operas, were printed with transposed parts for the recorder. The latest professional music, especially duets, solo and trio sonatas, was published for the consumption of the avid amateur. Professionals wrote some easy music especially for amateurs and gave away some professional secrets in the many recorder tutors which included also the latest airs and dances. However, with the emergence of the transverse flute in the 1720s, most of the amateur audience shifted to this new "à-la-mode" instrument, leading to the recorder being seldom used in the Classical and Romantic periods, and the recorder was only little used in the Classical and Romantic periods.

By the 1930s, with the pioneering work of Alfred Dolmetsch and Peter Hoga,n the recorder gained a new revival and became again popular in several European countries for the "Musische Bildung" (musical education) of the youth, especially in Germany with the so-called "German Recorder Movement." Until our days, the recorder remains the most popular educational and amateur instrument, and with the early-music revival it has likewise attracted an increasing number of skilled professionals.

Structure

The early recorders were first made of one, later of two pieces of wood, in the late Baroque period then of three pieces to get a more accurate bore. The essential feature is the head with the internal plug ("block"), leaving the windway (duct) to lead the player's breath to a rigid sharp edge or "lip" (voicing edge) at the base of the mouth ("labium").

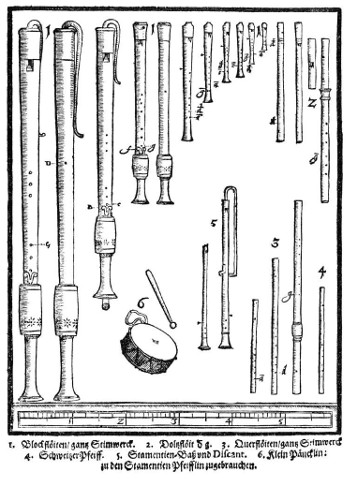

Michael Praetorius, Musica Syntagma II

(1618–1619)

The recorder as part of the family of duct flutes is distinguished from the others by having holes for seven fingers and a single hole for the thumb on the back side which also serves as an octaving vent. Medieval and Renaissance instruments had up to nine holes, Baroque recorders sometimes eight.

Recorders are made in different sizes corresponding to the different vocal ranges (fig. 7). The four main instruments used today are the "descant" (or "soprano," lowest note c'), the "'treble" (or "alto," lowest note f'), the "tenor" (lowest note c'), and the "bass" (lowest note f). The treble and tenor are non-transposing instruments, but the music for the sopranino, descant, bass, and great bass is usually written an octave below their sound pitch.

Playing Technique

on a Baroque alto-recorder (contemporary woodcut, probably in J.-M. Hotteterre's L'art de

préluder, 1719).

Although the design of the recorder has changed over its 700-year history, notably in fingering and bore profile (see History), the technique of playing recorders of different sizes and periods is much the same. Indeed, much of what is known about the technique of playing the recorder is derived from historical treatises and manuals dating from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. The following describes the commonalities of recorder technique across all time periods.

The recorder is held vertically from the lips (fig. 8), unlike the "transverse"-flute which is held horizontally. For the most part the tone of recorder is determined by its maker. Differences in design together with the kind of wood from which it is made make a remarkable variation in tone color. The player can influence the tone principally by manipulating the breath pressure. A notable feature of the recorder is the lack of resistance to air pressure afforded by the instrument itself. In this it is very unlike other wind instruments. Though learning to control the release of a steady stream of air under tension without a back-pressure to assist is essential.

The earliest treatises and tutors, such as those by Sebastian Virdung (1511) and Martin Agricola (1528), were generally aimed at amateurs and revealed some professional secrets, yet they collectively offered limited guidance on performance. The first book entirely devoted to recorder playing was Sylvestro Ganassi's Opera intitulata Fontegara (1535) (fig. 6). It gives stimulating insights into the professional standards, describing an astonishingly well-developed technique and expressive style of playing, founded on imitation of the human voice and achieved by good breath control, alternative fingerings, a wide variety of tonguing syllables, and extensive use of graces and complex diminutions.

.

Francesco del Cossa (1476–1484)

Salone dei Mesi, Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara

As well as writing hundreds of sonatas and concertos, mainly for the flute, Quantz is known today as the author of Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen (1752) (titled On Playing the Flute in English), a treatise on traverso flute playing. It is a valuable source of reference regarding performance practice and flute technique in the 18th century.

Iconographic Meaning

In many medieval and Renaissance paintings which represent angelic consorts, angles are shown playing recorders along with other instruments. In several paintings there are trios of angel recorder players, perhaps a sign of the Holy Trinity, like the music had often been in three parts.

In the late fifteenth century, the symbolism of the recorder gradually shifted away from the sacred meaning. In one of Francesco del Cossa's monumental frescoes in the Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara, in the Triumph of Venus a young woman in a group of other young men and maidens with musical instruments (lutes) holds a pair of recorders (fig. 8), representing sexual union and fertility.

In pastoral paintings, recorders were commonly found in the hands of shepherds (fig. 10 & 11) as well as courtiers and others in Arcadian guise. The recorder's frequent appearance in "Vanitas"-paintings, which depict the vanity of the worldly pleasures, presumably represents the transience of purely sexual love.

Hendrik ter Brugghen

1621

Oil on canvas

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Kassel

Johan Baeck

1637

Oil on canvas, 76.5 x 63.8 cm.

Private collection

Recorder Sources:

- Buijsen, Edwin and Louis Peter Grijp, eds. The Hoogsteder Exhibition of Music and Painting in the Golden Ages. The Hague: Hoogsteder and Hoogsteder; Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, 1994.

- Caughill, Donald. "A History of Instrumental Chamber Music in the Netherlands during the Early Baroque Era." Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 1983.

- Dart, Thurston. "Four Dutch Recorder Books." Galpin Society Journal 5 (March 1952): 57-60.

- Finlay, Ian. "Musical Instruments in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Paintings." Galpin Society Journal 6 (July 1953): 52-59.

- Griffioen, Ruth van Baak. Jacob van Eyck’s Der Fluyten Lust-hof (1644-c1655). Utrecht: Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis, 1991.

- Grijp, Louis Peter. "Dutch Music of the Golden Age." In The Hoogsteder Exhibition of Music and Painting in the Golden Ages, edited by Edwin Buijsen and Louis Peter Grijp, 63-80. The Hague: Hoogsteder and Hoogsteder; Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, 1994.

- Griscom, Richard and David Lasocki. The Recorder: A Research and Information Guide. New York: Routledge, 2003.

- Hooker, Mark T. The History of Holland. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999.

- Lasocki, David. "Gaps in our Knowledge of the Recorder in the Seventeenth Century and How They Could be Filled." In The Recorder in the Seventeenth Century: Proceedings of the International Recorder Symposium in Utrecht 1993, edited by David Lasocki, 257-276. Utrecht: STIMU Foundation for Historical Performance Practice, 1995.

- Lasocki, David, ed. The Recorder in the Seventeenth Century: Proceedings of the International Recorder Symposium in Utrecht 1993. Utrecht: STIMU Foundation for Historical Performance Practice, 1995.

- Legêne, Eva. "The Early Baroque Recorder: 'Whose lovely, magically sweet, soulful sound can move hearts of stone.'" In The Recorder in the Seventeenth Century: Proceedings of the International Recorder Symposium in Utrecht 1993, edited by David Lasocki, 105-126. Utrecht: STIMU Foundation for Historical Performance Practice, 1995.

- Legêne, Eva. "The Rosenborg Recorders." Journal of the American Recorder Society 25/2 (1984): 50-52.

- Morgan, Fred. "A Recorder for the Music of J.J. van Eyck." Journal of the American Recorder Society 25/2 (1984): 47-49.

- Noske, Fritz. Sweelinck. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Rasch, Rudolph. "Some Mid-Seventeenth Century Dutch Collections of Instrumental Ensemble Music." Tjidschrift van der Vereniging voor Nederlandse Musiekgeschiendenis XXII/3 (1972): 160-200.

- Rasch, Rudolph, ed. 't Uitnement Kabinet, Vol 1-10. Amsterdam: Muziekuitgeverij Saul B. Groen, 1973-1978.

- Tollefson, Randall. "Van Noordt." Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed 15 July 2004), http://www.grovemusiconline.com.

- Traficante, Frank. "Divisions." Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed 8 June 2005), http://www.grovemusiconline.com.

- Van Heyghen, Peter. "The Recorder in Italian Music, 1599-1670." In The Recorder in the Seventeenth Century: Proceedings of the International Recorder Symposium in Utrecht 1993, edited by David Lasocki, 3-64. Utrecht: STIMU Foundation for Historical Performance Practice, 1995.

- Vinquist, Mary. "Recorder Tutors of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: Technique and Performance Practice." Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1974.

- Wind, Thiemo. "Van Eyck: Introduction." Jacob van Eyck Quarterly 1 (2001). http://www.jacobvaneyck.info.

The Recorder on the Web:

- The Recorder Home Page

http://www.recorderhomepage.net/index.html - American Recorder Society (ARS)

http://www.americanrecorder.org/ - The Society of Recorder Players (UK):

http://www.srp.org.uk/index.htm - Dolmetsch Musical Instruments (UK) (related mainly to the recorder)

http://www.dolmetsch.com/index.htm - Nicolas S. Lander: The Recorder: Instrument of Torture or Instrument of Music?:

History of the Recorder'

http://www.recorderhomepage.net/torture2.html

Evert Colliers (fl. 1640–1710)