Click here for period cittern music:

The Voice of the Ghost

Anthony Holborne (?-1602)

Performed by: Lee Santana

The cittern was one of the most popular musical instruments of the mid-seventeenth century and it was also the one most frequently depicted by Vermeer. Although its form may recall the more familiar lute, it has a very different history and, above all, it produces a very different sound making it adapted for different music. The cittern's strings are made of metal while the lute's are of natural animal gut. In particular, the brass strings of the cittern, played with a plectrum, sound much louder, also because they are played with a plectrum. Its sprightly and cheerful sound is comparable to the modern banjo although a good cittern sounds a bit like the virginal. Instead, the lute is plucked by the bare fingers and produces a softer, nostalgic tone.

We find five citterns represented in Vermeer's approximately thirt-five or thirt-six extant paintings even though the whole instrument is visible only in The Love Letter (fig. 1). The work's crystalline edges and brilliant color scheme which sparkles with life, seem suggestive of the cittern's own tonal properties. The artist may have chosen to depict the cittern because of its particular iconographical meaning which was more evident to his viewers although the possibility that its curious, almond-like form also appealed to his aesthetic sensibilities cannot be ruled out.

c. 1667–1670

Oil on canvas, 44 x 38.5.cm. (17 3/8 x 15 1/8 in.)

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

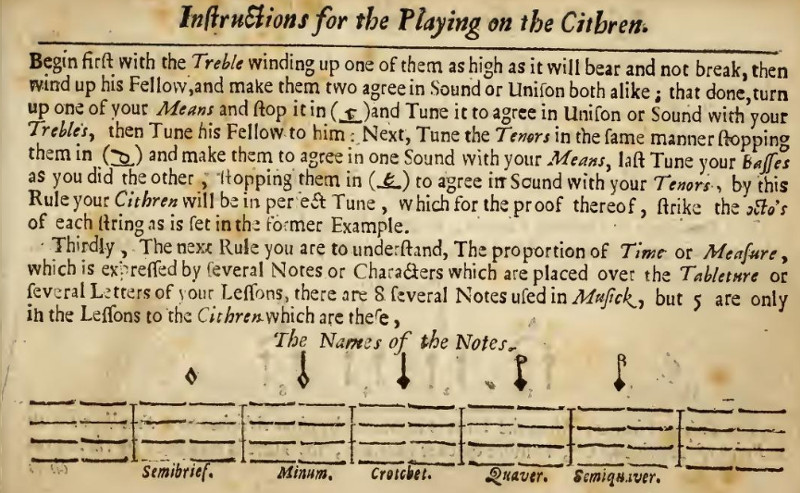

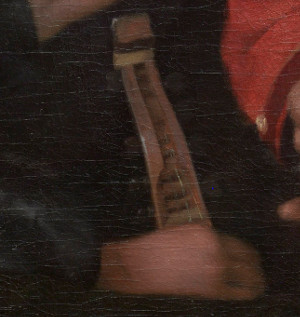

In three paintings, The Concert (fig. 2), The Girl Interrupted in her Music (fig. 3), and The Glass of Wine (fig. 4) the cittern lies partially hidden on a table or chair, yet the more informed viewer can easily identify its typical flat body, distinct from the pear-shaped body of the lute. In the early Procuress (fig. 5) instead, its distinctively ornately carved peghead unmistakably identifies it as a cittern. In the Girl Wearing a Pearl Necklace a neutron autoradiographic image demonstrates that a cittern (fig. 6) was also included a sixth time (it was set upon the foreground chair), but it was later painted out by the master himself for unknown reasons.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1663–1666

Oil on canvas, 72.5 x 64.7 cm.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1658–1661

Oil on canvas, 39.3 x 44.4 cm.

Frick Collection, New York

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1658–1661

Oil on canvas, 65 x 77 cm.

Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Johannes Vermeer

1656

Oil on canvas, 143 x 130 cm.

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 55 x 45 cm.

Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

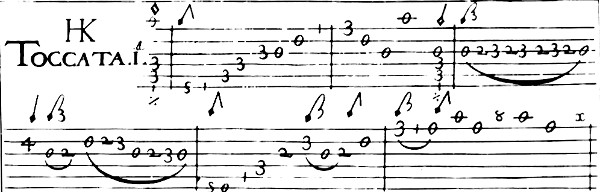

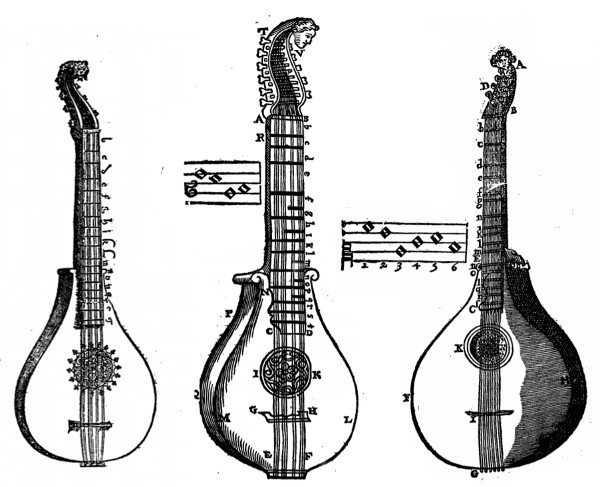

History

In Italian Renaissance humanist culture the cittern was regarded as a classical revival of the ancient Greek kithara (from which its name derives; see Winternitz) (fig. 7), but it seems to have its direct development from the medieval citole and also shares similarities with the fiddle, as its plucked form. There are no surviving instruments from the early period, but various iconographic sources including intarsie, miniatures in manuscripts, or sculptures. The composer and theorist Johannes Tinctoris seems to describe an early kind of the cittern in his De Inventione (c. 1487): "Yet another derivative of the lyra is the instrument called cetula by the Italians, who invented it. It has four brass or steel strings ... and it is played with a quill. Since the cetula is flat, it is fitted with certain wooden elevations on the neck, arranged proportionately, and known as frets. The strings are pressed against these by the fingers to make a higher or lower note."

The structure and tuning of the cittern varied almost from country to country. While in England, France and northern Europe the small four-course-instrument was mainly used, Italian musicians preferred the larger six-course instrument.

The cittern achieved its greatest importance in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In Italy and England, it was particularly esteemed, serving both as an accompaniment for the singing voice and for dance music. Later, many compositions were written expressively for it, often intricate and difficult to play. The first printed books, principally with pieces by Guillaume Morlaye, Pierre Phalèse, Robert Ballard, and Adrian Le Roy (with instructions for tuning and stringing) were published in France and Flanders (1552–1582).

The first published Italian music for the cittern was Paolo Virchi's Il primo libro di tabolatura di citthara (1574) for a fully chromatic six-course instrument, which demanded considerable technical virtuosity. One of the renowned Italian makers of string instruments was Girolamo Virchi, the father of Paolo Virchi, of Brescia, a center for musical instrument making in that time. Some of his instruments have survived (fig. 8), among them the lavishly decorated cittern made for Archduke Ferdinand of Tyrol.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Cittern medley: The Queen's Delight, Lady Nevilles's Delight, The King's Boure'e ( 1666)

John Playford (1623–1686/7)

Performed by: Dante Ferrara

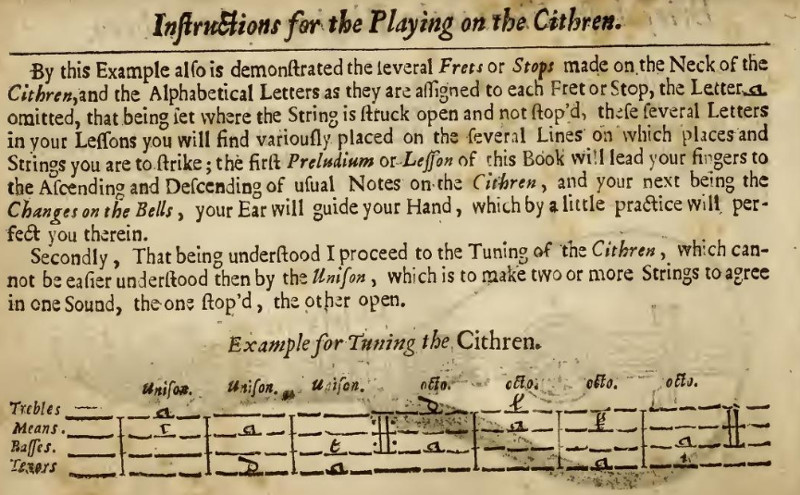

The best-known cittern works today come from England. Some of the most developed works for cittern were published there, yet only a few decades later the cittern was out of fashion. In England the first cittern music appeared in the mid-sixteenth century in the Mulliner Book with eight pieces for four-course cittern and one for five-course cittern. The most famous English composers were Anthony Holborne with his well-known Cittharn Schoole (1597) and (A Booke of New Lessons for the Cithern & Gittern, 1652). John Playford (1623–1686/7) was a London bookseller, publisher, minor composer, and member of the Stationers' Company, published various books on music theory, instruction books for several instruments, including the cittern (Musick's delight on the cithren : restored and refined to a more easie and pleasant manner of playing than formerly, and set forth with lessons al a mode, being the choicest of our late new ayres, corants, sarabands, tunes, and jiggs: to which us added several new songs and ayres to sing to the cithren) (fig. 9). In order to meet competition from purveyors of cheap music, Playford established a music concert to be held three evenings in the week at a coffee house. Here his music was to be sold, and might be heard at the request of any prospective purchaser.

Despite the predominance of psalms and distaste for frivolous songs and music, "Playford was likely seen as a turning of the tide and was bold enough to publish his book of country dances, but the more knowledgeable musical historians recognize Playford as a pioneer in musical publication England. The country dance book of 1650–1651 had its simple tunes very rudely printed from movable type and the music was neither barred nor harmonized. The one hundred and four tunes were popular airs and well selected from a musical point of view. Most of them were put into print for the first time, from tradition, and the whole book in its successive editions is a treasure-house of the popular tunes of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. Indeed, had it been absent much of our richest folk-music would have been forever lost."Frank Kidson, "John Playford, and 17th-Century Music Publishing," The Musical Quarterly 4, no. 4 (October 1918): 519.

Published music for the cittern in Germany is mainly represented by Sixt Kargel. The first two editions of his Renovata Cythara (1569 and 1575) are lost, but a reprint of 1580 survived. In the seventeenth century Michael Praetorius suggested using citterns in his vocal publications Polyhymnia (1619). A later seventeenth-century German development is a small, bell-shaped instrument, known as "Cithrinchen" (little cittern) which had its own repertory, but retains most of the classical characteristics of the cittern. In South Germany and the German-speaking areas of Switzerland the cittern remained in use until the early twentieth century, but with some of the constructional features of earlier citterns. The various names like "Bergzither" (mountain) or "Thüringer Waldzither" (forrst) indicate its use mainly in traditional folk music. "The popularity of the cittern in the Netherlands, particularly in the first half of the seveneteenth century, is highlighted by the fact that in Amsterdam the word 'cittern maker' applied to the builders of all stringed instrument. It is also significant that the 1647 catalogue of the Amsterdam bookseller Hendrik Laurentius contains a remarkable amount of cittern music, including the volumes by Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (printed in 1602 and reprinted in 1608) and Michiel Vredeman—Vredeman intended his cittern pieces for an international market given their Latin titles and inscriptions—which have since been lost."Jan W.J. Burgers, The Lute in The Dutch Golden Age: Musical Culture in the Netherlands 1580-1670 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2013), 150.

Marin Mersenne

1636

Paris

Dutch Citterns

Although depictions of citterns (fig. 10 & 11) abound in seventeenth-century Netherlands, little is known about period cittern construction and cittern music. While representations of citterns might suggest harmonious relationships, their presence may also evoke erotic overtones. Music was regularly performed in taverns to lure customers, and dance halls frequently doubled as brothels. Additionally, music halls customarily provided musical instruments for use by their patrons, who were urged to join in the performance. Vermeer's boisterous The Procuress provides an example of such circumstances.

Although instrument makers could be found in larger cities throughout the Netherlands, musicians of the higher class sometimes preferred to import instruments from more specialized centers across Europe.

Dutch painters frequently portrayed themselves playing a musical instrument, usually a stringed instrument such as a lute or cittern. Such pictures have been interpreted as an attempt to elevate the status of painting among the arts, which many in the seventeenth century still considered a craft devoid of intellectual merit. However, since music was in theory based on mathematics, by portraying themselves as musicians painters may have wished to elevate their social position in the eyes of their viewers.

Pieter van Slingeldant

1677

Oil on canvas

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

de Young, San Francisco

Jan Miense Molenaer

c. 1630- 1632

Oil on canvas, 68 x 84 cm.

National Gallery, London

Two Dutch cittern Recovered from the XVII century

Research and reconstruction by Sebastián Núñez & Verónica EstevezSebastián Núñez and Verónica Estevez, "A Dutch Cittern from the XVII Century (Collection NISA-Lelystad-The Netherlands): Research and Reconstruction," Maker of fine Early Musical Instruments: Lutes, Vihuelas, Early Guitars & Harpsichords - Specialized Restorer of Historical Guitars, Accessed November 24, 2023.

In the seventeenth century, the Zuider Zee was a dangerous inland sea where many ships were wrecked. In modern times hundreds of shipwrecks were unearthed during the reclamation of the IJsselmeer polders. The scattered location of the wrecks gives a good picture of the former intense ship traffic on the Zuiderzee. Although many shipwrecks lay on agricultural plots, on August 19, 1980, a crane operator stumbled upon a wreck of an almost complete ship during ground work on Gordiaandreef in Lelystad in the middle of an area that was under development. The ship's cargo proved to be so precious that it was decided in 1981 to excavate and store the ship and its contents. The wreck was transported in a metal frame to its temporary storage facility where it was preserved under a plastic tent. Within two years, the humidity under the tent had been slowly reduced from 95% to normal values, which allowed the wood to dry. By 1984, the ship was dry to such an extent that the tent could be removed and the ship's contents conserved by slowly replacing the remaining water with PEG (polyethylene glycol, a waxy substance) so that the wood retains its shape.

The wreck was 18.85 meters long and 5.15 meters wide. Two coins from 1614 and 1619 provide the earliest approximate date of its sinking, (namely 1619). This was a type of ferry ship which connected Amsterdam with other cities in the north like Kampen or Zwolle. Because it was found lying on its side at an angle of 50 degrees, the vessel's contents had shifted to its lower side and were preserved in good condition under the mud. At least five hundred objects were recovered, among which were a number of well conserved pieces of two citterns—it is quite unusual to find musical instruments in shipwrecks, especially string instruments. After patient research and analysis, Early Musical Instruments specialsits Sebastián Núñez and Verónica Estevez were able todraw detailed plans that allowed them to reconstruct both citterns, which appear to be typical four-course Dutch citterns, comparable to those represented in many Dutch artworks of the Golden Age. Each one has, for example, ten strings separated in four courses (two double strung and two triple strung) as we see in many paintings and engravings of the period.

The complete research on the citterns has been published by Kloster MIchaelstein, Blankenburg, Germany in 2004.