The Eighty Years' War (c. 1566/1568–1648) , which lasted a large part of the seventeenth century, was fought principally for religious and economical motives. Its outcome was complete independence from Spanish dominion for the reformist northern provinces. During the war, the Dutch Republic rose briefly as a world power and experienced a period of unprecedented growth.

This sudden and dramatic flourishing of maritime commerce gave birth to a large, wealthy merchant class, and an economic prosperity which fostered enthusiasm and lucrative sponsorship for the visual arts, literature, and science. But while the art of painting blossomed into a true Golden Age, Dutch music did not. Music had largely ceased to play an important role as it did in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries with the famous Franco-Flemish musicians and composers Guillaume (Willemet) Du Fay (1397–1474), Johannes Ockhegem (c. 1425–c. 1497) or Orlandus (Roland) Lassus (1530/32–1594). After the abdication of Charles V, who had always supported the Netherlandish musicians, the cultivation of music in the courts of the Habsburg Stadtholders was no longer deemed as vital as it had been before.

The principal explanation for the lack of inspiration in Dutch music during the Golden Age of painting has been attributed to diverse circumstances, among them, the dampening role of the dominant Calvinist religion who frowned on all music during church services except for unaccompanied communal singing. Thus, without significant church and aristocratic patronage, there was "little incentive for major artistic innovations."Louis Peter Grijp, "Dutch Music in the Golden Age," in Music and Painting in the Golden Age, eds. Edwin Buijsen and Louis Peter Grijp (Zwolle: Waanders, 1994), 63.

"As we see it today, the strength of Dutch art lies not so much in its history pieces as in still-lifes, landscapes marines, portraits and genre painting and suchlike. Similarly the strength of Dutch music lies not in the intricate polyphonic or Baroque compositions, but in that simplest of all genres—the song, that enjoyed an incomparable bloom here. This musical strength lay in the sheer delight in singing found among people of all classes, in an appetite for music that was fed and stilled not so much by composers as by poets. And it was the same people who were consumed by a desire for paintings and who bought them for their homes."Louis Peter Grijp, "Dutch Music in the Golden Age," in Music and Painting in the Golden Age, eds. Edwin Buijsen and Louis Peter Grijp (Zwolle: Waanders, 1994), 78.

It may be said that only one Netherlandish musician made a significant contribution to European musical history—so let us have a closer view to the life and work of Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck.

Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck

born: Deventer, May 1562

died: Amsterdam, 16 October, 1621

Jans Pieterszoon Sweelinck (fig. 1) was born into a family of musicians, as the elder son of Peter Swybbertszoon an Elske Sweeling. Swybbertszoon. His grandfather Swibbert and his uncle Gerrit Swybbertszoon had both been organists at the Cathedral of Deventer. Soon after Jan's birth his family came to Amsterdam where his father became the organist at the Oude Kerk and remained there until his death 1573. The position was kept vacant for his son until 1580.

As was usual in those times, Sweelinck received his first musical instruction from his father. After his father's death, he completed his studies with Jan Willemszon Lossy, a countertenor and shawm player at Haarlem. Lossy was not an organist but just the same he may have taught Sweelinck composition. It is assumed that he listened to the famous organists at Saint Bavo in Haarlem, Claas Albrechtszoon van Wieringen and Floris van Adrichem.

Cornelis Boskoop, who briefly succeeded his father at the Oude Kerk in 1573, may have been among Sweelink's organ teachers. Within the age of about 18, he took the position of organist at Oude Kerk, Amsterdam. 1585, after the death of his mother, Sweelink had to take care of his younger brother and sister. Sweelinck had adopted his mother's family name for as unknown reasons (first using it on the title-page of his Chansons of 1594). In 1590 he married Claesgen Dircksdochter Puyner and had five children.

Attributed to Gerrit Pietersz Sweelink (the musician's brother)

1606

Oil on panel, 67 × 52 cm.

Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague

Contrary to tradition, Sweelinck was not engaged as organist or carillonneur. Nor did his duties include supplying music for regular ceremonial and social occasions of the city magistrate, as was the practice in many other cities. Since Calvinists viewed the organ as a worldly instrument and forbade its use during services, Sweelinck was actually a civil servant employed by the city of Amsterdam (which in any case owned the organs). It is generally assumed that his duty was to provide music twice a day in the church—once hour in the morning and once in the evening.

Sweelinck was well known for his organ and harpsichord improvisations: more than once proud city authorities brought important visitors to the church to hear the "Orpheus of Amsterdam." A large organ with three manuals and pedal (originally by Hendrik Niehoff in 1539–1545), and a small one with two manuals and pedal (1544–1545 by Niehoff and Jasper Johanszoon) were at his disposal in the Oude Kerk.

Sweelinck was not only a high talented organist but a gifted teacher as well. His teaching made him famous throughout northern Europe and founders of the so-called north German organ school of the seventeenth century (culminating in Bach) were among his pupils. His Dutch pupils included talented dilettantes and young professional musicians. The most important were Anthoni and Sybrandus van Noordt, Cornelis Janszoon Helmbreecker and his own son Dirck or Willem Janszoon Lossy (son of his Haarlem teacher). One of his amateur pupils was Christina van Erp, wife of the famous Dutch poet Pieter Cornelisz. Hooft.

After the turn of the century, Sweelinck's reputation attracted pupils from Germany such as Andreas Düben, Samuel and Gottfried Scheidt, as well as Jacob and Johannes Praetorius and Heinrich Scheidemann. The pupils of "Master Jan Pieterszoon of Amsterdam" were musicians against whom other organists were measured. For this reason promising young men were sent to study with him financed by their city councils. The costs, which included instruction, room and board at Sweelink's house (as it was customary in those days), may have totaled two hundred florins a year per student, a conspicuous sum for the time. An average house was could be bought at approximately five hundred florins a year while a year of study with Rembrandt van Rijn cost one hundred guilders.

Sweelinck was the last important composer of his age in the Netherlands. His keyboard music is now understood to be less the work of an innovator than of one who perfected forms derived from, among others, the English virginalists (notably Bull and Philip) and transmitted them through his pupils. His immediate influence can be seen in the music of Samuel Scheidt and Anthoni van Noordt.

Apart from several pieces for the lute which are preserved in the famous Luitboek van Thysius and the Luitboek van Edward Herbert, Sweelinck's instrumental music was composed entirely for keyboard instrument. It reveals a thorough knowledge of every major keyboard tradition of his time, especially the English (for instance the Engelsche Fortuyn or Onder de linde groene / All in a Garden Green) and the Venetian. Although Sweelink's instrumental music was never printed, it nonetheless enjoyed wide circulation through the copies made by his pupils.

Sweelinck's polyphonic setting of the Psalter (first vol. 1604) has been justifiably called a monument of Netherlandish music, unequalled in the sphere of sacred polyphony. The texts are drawn from the French metrical Psalter of Marot and Bèze, not the Dutch version of Datheen (1566) used in most Dutch churches until 1773. This was probably because the psalms were not intended for use in public Calvinist services but rather within a circle of well-to-do musical amateurs among whom French was the preferred language.

Sweelinck's other important vocal collection, the Cantiones sacrae (1619), is the musical and religious antithesis of the psalms. It comprises 37 motets on texts from the Catholic liturgy. This fact raises the question as to whether Sweelinck remained a Catholic in the service of the ruling Calvinist minority.

Sweelinck's surviving output amounts to 254 vocal works, including 33 chansons, 19 madrigals, 39 motets and 153 psalms, as well as about 70 keyboard works, principally in the form of fantasias, echo fantasias, toccatas and variations.

Sweelinck led an uneventful, harmonious life. His few documented absences from Amsterdam were entirely related to his professional activities. He inspected new organs at Haarlem (1594), Middelburg (1603), Nijmegen (1605), Rotterdam (1610, where he had to act as an adviser for the improvements of the organ in the Laurenskerk), Dordrecht (1614) and the restored or repaired organs at Harderwijk (1608), Delft (1610), Dordrecht (1614) and Deventer (1616) – his birthplace, which he had also visited in 1595, perhaps to give advice about the forthcoming restoration of the organ. His longest journey was in 1604 to Antwerp, where he purchased a harpsichord (possibly by Ruckers) for the city of Amsterdam.

Sweelinck was buried in the Oude Kerk. He was survived by his wife and five children, of whom only the eldest, Dirck Janszoon Sweelinck, was a musician.

Forms of Musical Culture

Sweelinck's career demonstrates the basic elements of the seventeenth-century Netherlandish musical life. Music was cultivated chiefly under the auspices of the Calvinist church. Although there was no productive cultivation of church music (for a while even the playing of the organ during church services was forbidden) the organ held an important position in instrumental music. Sometimes—as an official document of Leiden states—the authorities ordered that organ recitals should be given before and after Sunday services and on weekdays to keep the people away from the inns and taverns. The value that the authorities placed on public organ recitals in their town churches resulted in the construction of an almost incalculable number of the finest organs, both in the Netherlands and abroad. Dutch organ builders had a significant influence on the development of a variety of characteristic "organ landscapes," for example in the north German area (Hamburg).

Click here MP3 audio-file of:

Jacob van Eyck, Buffons, from Der Fluyten Lust-Hof II,

Performed by Marion Verbruggen, 1996

Buffons:

The only group of variations on a bass-line, rather than a melody. The dance from which the bass pattern originates seems to have been a sword dance, serious in origin but having become "buffoonish."

Suggested audio-file:

http://www.harmoniamundi.com/

usa/artistes_fiche.php?artist_id=42

Composers of the seventeenth century included Nicolas Vallet (c. 1583–after 1642), French lutist, settled in Amsterdam, 1616 Secretum Musarum—anthology of three collections of lute compositions, 1620 Regia pietas—lute settings for all 150 Psalms); Cornelis Thymansz. Padbrué (c. 1592–1670, composer of Dutch madrigals like the Kusjes [Kisses] translated from the Latin by Jacob Westerbaen, collaboration with the famous poet Joost van den Vondel) or Adrianus Valerius (c. 1570–1625, prosperous burgher and amateur lutist), who wrote the epic Nederlantsche Gedenck-clanck [posth. 1626], a work which describes in words, pictures and songs the Netherlands fight for independence against the Spaniards, containing the Wilhelmus, the Netherlands national anthem. Valerius provided all the songs with popular melodies.

A form of musical culture peculiar to the Netherlands was the carillon, which still attracts the attention of foreign visitors. The immigrant brothers François and Pieter Hemony, noted for their unsurpassed accuracy in bell tuning, brought the indigenous art of bellfounding to a peak. In 1660, the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft received its carillon made by François Hemony in Amsterdam. He cast the thirtey-six bells using the remains of those from the city hall, which were badly damaged in a devastating fire in 1618. If carefully observed, no bells can be seen in tower of the Nieuwe Kerk in Vermeer's View of Delft. The carillon had been mounted between May 1660 and the autumn of 1661. Vermeer's empty tower thus reflects the situations before that time.

The carillon lead us to the next famous personage in the Netherlands musical life.

Jacob van Eyck

born: Heusden: near 's-Hertogenbosch, 1589/90

died: Utrecht, 26 March, 165

Jacob van Eyck was a Dutch carillonneur, bell expert, recorder player and composer. He was born blind and inherited the noble title of "jonkheer" from his mother's side. He spent his early years in Heusden. In 1623 he visited Utrecht, where he was appointed "beiermeester" (carillonneur) of the Domkerk in 1625. Three years later he became director of the Utrecht bellworks, having technical supervision over all the parish-church bells. Later he also became carillonneur of the Janskerk, the Jacobikerk and the city hall.

Van Eyck discovered the connection between a bell's shape and its overtone structure, which enabled bells to be tuned properly. The famous bellfounders François and Pieter Hemony had cooperated in this discovery. Van Eyck's work drew the attention of such prominent intellectuals as the Dutch scientist Isaac Beeckman, René Descartes (who lived in Utrecht for some years) and Constantijn Huygens (a distant relative, and dedicatee of Van Eyck's Der Fluyten Lust-Hof). Both Descartes and Huygens describe in their letters to the French music theorist Marin Mersenne how Van Eyck was able to isolate different partials in one bell without touching it: simply by means of whistling or humming the desired tone close to the bell and making use of the resonance principle (overtones).

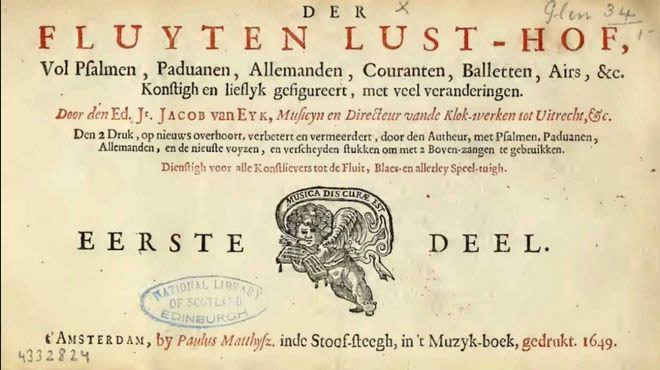

In 1649, Van Eyck's salary at the Janskerk was increased, "provided that he would now and then in the evening entertain the people strolling in the churchyard with the sound of his little flute," a practice that was first mentioned in a poem of 1640. His first collection for the soprano recorder, Euterpe oft Speel-goddinne (Amsterdam 1644) had been enlarged and became later the famous two-volume Der Fluyten Lust-Hof (fig. 2), which remains until today the largest work in European history written for a wind instrument. Moreover, it remains the only opus of considerable dimensions that was "dictated" by the author as he improvised on the flute. Therefore, the original print contained many errors, but the second print already appeared "op nieuws overhoort ... door den Autheur" (heard[!] through anew ... by the author) and was printed several times during van Eyck's lifetime.

The work contains almost 150 pieces for solo soprano recorder in C. A few of the pieces are free compositions (preludes and fantasias), but the majority consist in variations on popular melodies. Although most of them have Dutch titles, many originate from the French air de cour repertory. Some are Italian (from Giulio Caccini, Gastoldi), English (John Dowland), German and Dutch and sixteen were borrowed from the Genevan Psalter. The process of composing variations was called "breecken" (breaking) meaning that the notes of a theme were broken into notes of smaller values, each reprise becoming increasingly elaborate.

Despite of van Eyck's noble parentage and his connections to Huygens, he appears to have lived very simply. Whether the success of the Fluyten Lust-Hof did anything to improve his finances is not known.

Private Music Making

Joost Corneliszoon Droogsloot

1645

Oil on canvas, 97.7 x 126.8 cm .

Centraal Museum, Utrecht

Although people certainly enjoyed being entertained by professional musicians like Van Eyck, they also enjoyed making music themselves as so many Dutch paintings illustrate (fig. 3). Music making took place in the privacy of the home, especially in smaller towns where there were fewer public concerts and musical events than in the large cities like Amsterdam. Young people from the wealthy upper class spent their leisure time chatting and playing music in their homes. But the lower and peasant class took advantage of every occasion—weddings, seasonal feasts etc—to gather and make music. These so-called "merry companies," where eating, drinking, dancing abounded, furnished subject to an amazing number of Dutch genre paintings. A comparison between paintings by Jan Steen (fig. 4) and Vermeer (fig. 5) show wonderfully how both the sides of the '"coin" engaged each in their own music.

Jan Steen

c. 1663–1665

Oil on panel, 55.3 x 43.8 cm.

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 51.4 x 45.7 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Jan Steen

c. 1668–1672

Oil on canvas

Loud brash music, which was often accompanied by suggestive texts, was performed in taverns and in the streets (fig. 6). On the other hand, music was also enjoyed within the peaceful confines of one's own home. Even though the musical environments contrast so strongly, Vermeer's and Steen's paintings illustrate the same delight that all Dutchmen had for music and how important a role it must have played in their lives. Thus, it is not surprising that songbooks were published in great numbers. The Friesche Lusthof (1621) and the Oude en nieuwe hollantse boerenlieties en contredansen ("Old and new Dutch peasant songs and country dances"), published in Amsterdam 1700–1716, is the largest collection of popular melodies ever published in the Low Countries. It contains more than 1,000 melodies, many of French and English.