Last Five Years

The last five years of Vermeer's life raise important questions about both his private and professional life. The artist's economic status must have been greatly stressed, due to the costs of feeding and clothing an ever-growing family, as well as by the disastrous state of the Dutch economy brought on by the ruinous war with France that began in 1672, called the Rampjaar, "disaster year." The Dutch Republic was attacked by England, France, and the prince-electors Bernhard von Galen, bishop of Münster and Maximilian Henry of Bavaria, the bishop of Cologne. Despite heroic defenses and the fact that significant areas of agricultural lands were flooded to impede the invading armies, the Dutch States Army was defeated. Large parts of the Republic were conquered. Panic seized the remaining coastal provinces of Holland, Zealand, and Frisian. City governments were taken over by Orangists. A famous Dutch saying describes the condition of the Dutch population at that moment as redeloos (irrational), its government radeloos (desperate) and the country itself reddeloos (beyond rescue).

In front of the calamitous times, the Netherlands' painters suffered or were forced to improvise. The marine artists Willem van de Velde (c. 1611–1693) and his son went to England. In 1672, Jan Steen (c. 1626–1679), the successful painter of chaotic Dutch household life, put down his brushes and opened a brewery. Unable to find commissions, the fashionable portrait painter Bartholomeus van der Helst (1613–1670) went broke.

Delft and its citizens were called upon to dig a high earth rampart around their town for defensive purposes. While Delft was not directly involved in the conflict, it was flooded with refugees, especially from Tiel, overrun by the French.

Delft Militia

By 1674, Vermeer was a member of the Delft militia (Schutterij), which was formed to defend the town walls and protect its citizens. Members of the militia were selected from the town's wealthy burghers since the lower classes could not afford the appropriate equipment and uniform even though some local authorities had occasionally paid for the equipment. Officers and captains were appointed by the city magistrates; aside from their social origin, they had to be members of the Reformed Church. In the words of a Delft edict of 1655, members of the militia were "the most suitable, most peaceful and best-qualified burghers or children of burgers." Their pay, compared to their duties, was negligible consisting of a small subsidy or a (partial) release from certain taxes.. Nevertheless, the membership was a matter of civic pride, an honor that led to the development of a kind of "civic nobility" (burgeredeldom).

Vermeer was listed in the Schuttersboek as member of the first squadron of the Oranje Vendel, commanded by Abraham Coeckebacker. We know that the family friend of the Vermeers, Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674), had been a sergeant in the same company and a member of a select group known as the Brotherhood of Knights (broederschrappe). Two other important figures in Vermeer's professional life had played a role in the Delft militia. The first was Captain Teding van Berckhout, who headed the second banner of the third quarter. Van Berckhout had once described a visit to the Vermeer's studio in his diary. In any case, Vermeer's membership likely facilitated contact with wealthy collectors and potential clients..

We do not know when exactly Vermeer joined the militia or why he was accepted. Either the captains of the militia were unaware of the painter's difficult financial situation or by necessity or deference, they chose to ignore it. Perhaps the rules set down to guide the functioning of the militia were not practiced as rigidly as would be expected, especially in times of crisis. Nevertheless, Vermeer certainly enjoyed a good reputation of an honorable citizen. In any case, Vermeer had a pike and helmet in the front room of his house.

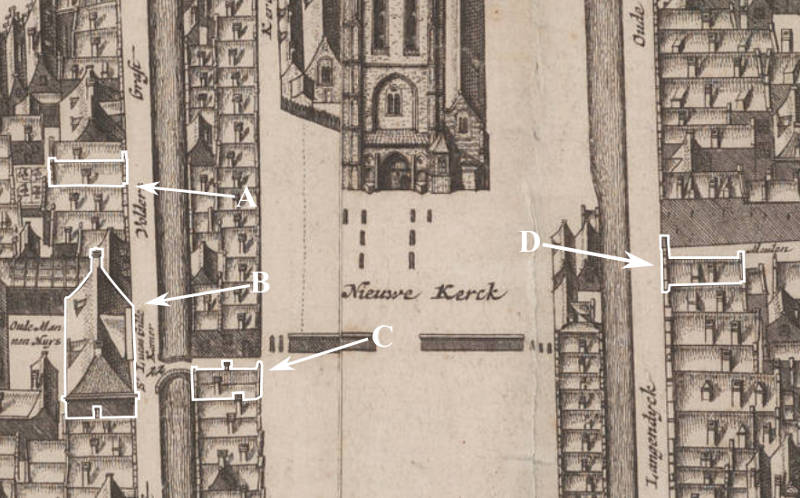

A. Flying Fox (Vermeer's presumed birthplace and inn of his father)

B. The Delft Guild of St. Luke (professional organization of artists and artisans)

C. Mechelen (a large tavern on the Market Square rented by his father where Vermeer and his family lived after the Flying Fox

D. Groot Serpent (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

E. Trapmolen (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

Last Paintings

Although art historians are loath to classify Vermeer's works in distinct groups, the works which were presumably painted between 1670 and 1675, the year of the artist's untimely death, show a remarkable evolution in style. Characteristic of these last works is the simplification of modeling and elimination of detail. Objects are described only in the broadest terms, compositions are more dynamic (sometimes imbalanced) and form is brittle. Curious stylistic flourishes, which resemble calligraphy rather than painting, abound. Abstraction and pattern are tenaciously pursued.

For many years art historians held that Vermeer's final works denote waning artistic powers. Today, the change in style is explained by artistic or economic motivations. Some historians equate the schematic nature of these works as a nod towards the classical prescriptions set down in writing by the Dutch painter and art theorist Gérard de Lairesse. De Lairesse exhorted painters, particularly those who specialized in "vulgar" subject matter (peasants brawling, drunken soldiers, crying babies and toothless old hags), that only through the emulation of antiquity and the proper treatment of history subjects could true art be produced, although he also advocated paintings of "modern life" (bourgeoisie interiors like Vermeer's) "cleansed of all imperfections." Others have seen Vermeer's move away from the naturalism and detached observation of his earlier as a response to increasingly invasive French influence in arts and fashions. More banally, the new, abbreviated style may have permitted a higher output in times when money for expensive pictures had severely dwindled.

In 1671, Vermeer, with various colleagues including Johannes Jordaens, Jan Lievens (1607–1674), Melchior d'Hondecoeter (1636–1695) and Gerbrand van den Eeckhout (1621–1674) were called upon to pronounce on the authenticity of 13 disputed paintings, most "Italian," and some sculptures acquired by Frederick Wilhelm, the Grand Elector of Brandenburg from the art dealer Gerrit van Uylenburgh (c. 1625–1679). On the advice of Hendrick Fromantiou (1633/4–after 1693), a Dutch still- life painter, Wilhelm accused them of being counterfeits and had sent twelve back to Van Uylenburg. Van Uylenburgh then organized a counter-assessment, asking a total of 35 painters to pronounce on their authenticity. The paintings were put on public display in the Guild headquarters in The Hague. Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), one of the Netherlands' foremost statesmen and art connoisseurs, testified before a notary that the paintings were indeed authentic Italian works, although "some might be worth more than others." When Jordaens, an older Delft painter who had spent many years in Italy, and Vermeer, described as an "outstanding painter of Delft," testified, they sentenced the pictures were "not only not outstanding Italian paintings, but on the contrary, great pieces of rubbish and bad paintings, not worth by far the tenth part of the afore-mentioned proposed prices." Since there exists no evidence that Vermeer had been to Italy, he may have been consulted because he was a prominent figure in the Delft art scene and a two-time headman of the Saint Luke Guild of Delft.

The following year, the Rampjaar (Disaster Year) all but decimated the art market and threw Vermeer into a desperate economic situation.

The Rampjaar, led to flooding that destroyed harvests, resulting in food shortages and financial struggle for everyone.. For artists in Delft, selling their works became challenging as art became a luxury that few could afford. As a result, many artists faced financial crises. Notable artists like the Willem van de Veldes relocated to England, while others like Bartholomeus van der Helst and Johannes van der Meer faced bankruptcy. Jan Steen transitioned to innkeeping.

Vermeer's family also tightened their belts. Maria Thins, who typically earned from her farmlands, faced challenges as her land near Schoonhoven was flooded due to war strategies. This meant no income from those lands as crops couldn't be grown and farmers couldn't pay rent. In 1675, Vermeer negotiated with a farmer, Jan Schouten, to waive rents from 1673 and 1674 due to these challenges. By 1676, Maria Thins had unpaid rents amounting to over 1,600 guilders. Amid these challenges, Vermeer took on various responsibilities, including leasing out properties and securing loans. Once financially comfortable, Maria Thins had to reduce the financial help she provided to her daughter and son-in-law.Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2002), 190-191.

Notwithstanding a ballooning family, deteriorating social and economic conditions, the near forty-years-old-painter's attempt to reinvent his art in the first years of the 1670s produced canvases like The Love Letter, The Guitar Player (fig. 1) and the Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid which are among the artist's most innovative and finely crafted designs. Certainly, poverty, age, and the national calamity left no trace upon his choice of subject matter, although some brave writers have interpreted his paintings as "zones of safety, aesthetic safe havens where...peace exists." It might be remembered that Vermeer was hardly alone in his portrayals of domestic peace even in moments of personal and social tragedy. Whether his quietist paintings should be understood as conscious, semi-conscious or unconscious constructs meant to sublimate the pressures of internal or external violence rather than the painter's personal quest for painterly perfection, shall not easily be resolved.

The doorkijkje (see-through view) composition of the complicated Love Letter is one of the artist's most ambiguous yet evocative representations of pictorial space. The three rectangular partitions of the planimetric layout are so strongly emphasized that they effectively challenge the illusion of spatial depth artfully created by the recession of the black and white floor tiles and a series of conspicuously overlapping objects.Although overlap is the most primitive means for suggesting three dimensions on a flat surface, it is nonetheless the most unequivocal. One writer mistook the middle partition for a mirror set up against a dark wall in which an unseen room is reflected. Equally daring, the asymmetrical composition of the late Guitar Player—the sitter's elbow is lopped-off for no immediately apparent reason—assures us that the painter still has, or believes he has, more than one compositional trick up his sleeve. Even the composition of the minuscule Lacemaker, which might appear less complicated than the just cited works, is one of the artist's most imaginative designs despite the fact that the canvas is little more than a span high.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1673

Oil on canvas, 53 x 46.3 cm.

Iveagh Bequest, London

The Guitar Player attests Vermeer's ability to weave narrative and formal design into a seamless unity, one of the most notable achievements of the Delft painter. Rather than a trouble-free portrayal of a real musician, Elise Goodman persuasively argued that this picture is an ingenious indoor variation of the popular construct of the "lady and landscape" (originated in Italy) wherein exquisitely adorned female musicians are set against idyllic landscapes.Elise Goodman, "The Landscape on the Wall in Vermeer," in The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer (Cambridge Companions to the History of Art), ed. Wayne Franits (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 79–85. The ubiquitous idea that the lady was a masterpiece of nature, "to be admired, possessed, and displayed, appeared in countless poems, songs, and tracts on beautiful women in the seventeenth century."Elise Goodman, "The Landscape on the Wall in Vermeer," in The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer (Cambridge Companions to the History of Art), ed. Wayne Franits (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 81–82.

The lady-nature tie draws formal support, first noted by Lawrence Gowing, from the semblance of the dangling branches of the tree in the background landscape and the bouncing curls of the lady's stylish coiffure.This link was first pointed out by in; Lawrence Gowing, Vermeer (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1997). In regards to the musical theme, Wheelock connected the picture's dynamic, off-centered composition and crisp handling of paint to the sprightly music of the new-fashioned guitar which was beginning to overtake the melancholic strains of the venerable lute.

Thus, The Guitar Player, which at first glance might be mistaken for a literal portrayal of a shiny young woman with a shiny new instrument, discloses a refined discourse on female beauty, nature, music, love and, via the conspicuous manner in which it is composed and depicted, on the art of painting itself.From a painter's point of view, the canvas is a technical delight. The coloring and tonal transition of the musician's hands and arms are among the most refined in the artist's oeuvre. The gilt frame, the guitar's decorative sound hole and satin skirt demonstrate a level of pictorial synthesis, which almost verges on brutality, unseen in the work of any other Dutch genre painter. The bizarre, calligraphic brushwork hints at a mysterious subtext which however, remains illegible in any other than purely pictorial terms. Notwithstanding that this curious picture is hardly a favorite among Vermeer devotees, it suggests not to a depleted, end-of-career painter, but an artist still upright in his saddle, sensitive to the deeper cultural concerns of his age but likewise attentive to the caprices of fashion.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 51.7 x 45.2 cm.

National Gallery, London

A Lady Seated at a Virginal (fig. 3) and A Lady Standing at a Virginal (fig. 2) are considered by most critics to be the artist's last works. Some hold that they were conceived as a pendant. In effect, there exists much more evidence that joins rather than separates the two works. Their dimensions are nearly identical. The two young women play music on a finely crafted standing virginal decorated with faux marble side panels. Both perform in the left-hand corner of a room and are dressed in stylish clothing of the day. They both turn to look at the viewer as if they had been interrupted by someone outside the picture. Both rooms exhibit fine marble flooring with diagonally set black and white slabs. A picture-within-a-picture hangs on the background wall presumably to provide a visual comment on the scene below.

However, the overall atmosphere and compositional dynamics of each work are markedly different. The standing woman plays erect, her pose recalling the perfection of a classical column, bathed in sunlight which floods the room through an open window. In contrast, the seated woman crouches ever-so-hesitantly over her virginal shrouded in near obscurity. The blue curtain catches whatever light might have leaked through the closed shitters of the window. The pendant format does not imply identical treatment of a given motif. In fact, Dutch painters relished the opportunity to reveal opposing qualities of the same subject. These facts suggest that they represent opposite aspects of a single concept, such as, for example, Sacred and Profane Love.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1675

Oil on canvas, 51.5 x 45.5 cm.

National Gallery, London

Female keyboard players were a popular subject in seventeenth-century Dutch art. Music-making was often associated with love and at times with amorous seduction. For example, in verses by Jacob Westerbaen we read: "learn to play the lute, the clavichord. The strings have the power to caress the heart." The virginal, however, had highly civilized connotations since it was habitually played by a woman in the context of family or musical gatherings. Consequentially, they were often used by artists as a symbol of harmony and concord.

The unattended viol da gamba in the foreground of A Lady Seated further strengthens the association with harmony. The woman, like the male musician in Jacob Cats' (1577–1660) well-known emblem "Quid Non Sentit Amor," plays her instrument while a second lies unused. The emblem's text explains that the resonance of one lute echoes onto the other just as two hearts can exist in harmony even if they are separated. Vermeer probably painted very little in his last years.

Frenzy and Death

Vermeer, who had evidently won Maria Thins' utmost confidence, actively participated in the economic maneuvering in the very last years of his life. In June 1673, the artist petitioned the magistrates of Gouda in regards to a legacy of the Thins family. In July, he traveled to Amsterdam to sell two bonds, worth the sizable sum of 800 guilders. In January 1674, he also acted as a witness for recognition of debt regarding his sister Gertruy. Three days later, he was again acting on behalf of his mother-in-law when later he accompanied Maria Thins and signed a deposition regarding the legal guardianship. At the end of March, Vermeer, noted as "Sr Johannes Vermeer, master painter," witnessed yet another document regarding his mother-in-law.

On April 4, 1674, Maria Thins' ogre husband died and was buried in the Church of Saint Jan in Gouda, which was adorned by a stained-glass window that featured effigies of Dirck Cornelisz van Hensbeeck Oudwater and his wife Aechte Hendricksdr., Maria Thins' parents, who had made important donations to the church.

In May 1673, Vermeer, representing his wife Catharina, appeared with Maria Thins in regards to money inherited by Catharina and her brother Willem.

One of the few bright spots in the dark gray sky of the final years of the artist's life was the marriage of his eldest daughter, Maria, to Johannes Gillsz. Cramer, the son of a well-to-do silk merchant, making Maria the only one of Vermeer's children who had been able to reach economic independence in the artist's lifetime.

In March, 1675, Maria Thins entrusted the "honorable Johannes Vermeer" to act in her name in the division of the estate of her late husband in favor of her son Willem. A few days later he traveled to Gouda again to act on Maria Thins' behalf to renew leases on farmland.

In July, he traveled to Amsterdam to borrow 1,000 guilders for a local merchant. This transaction may be the only incidence that sullies the confidential relationship between the painter and his mother-i- law, and perhaps, was counter to the law itself. From a document dated after Vermeer's death, 14 months later, we discover that Maria Thins had entrusted her trusted son-in-law to collect the considerable sum of 2,900 guilders from the Orphan Chamber in Gouda to which she was entitled. Instead of holding onto the sum as agreed, Vermeer had pawned the obligations to the already mentioned Amsterdam merchant for 1,000 guilders. Maria later returned the obligations to the Orphan Camber as required by law. Montias was puzzled by the fact that Vermeer could have been so desperate that he would act in such a way, "if he really did," maintaining that such behavior would be completely "out of character with the whole life of the artist." "I," writes Montias, "am inclined that Maria Thins may have distorted the story, perhaps to reduce her responsibility in the affair."John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 212.

Vermeer died at the age of forty-three on December 13 or 14. His coffin was brought to the Oude Kerk and below the church floor in the family tomb which already contained the bodies of three of his children. The tomb had been purchased by Maria Thins on December 10, 1661. The exact location of the family tomb is not known but the city of Delft has installed a commemorative plaque (fig. 4).

Vermeer is buried in the Oude Kerk, in Delft. He leaves an impoverished widow and eleven children, ten of whom are still minors. Thus, Vermeer, a renowned art-painter, was buried on 15 December 1675, as recorded in the Oude Kerk register. Though the register mentions eight underage children, Vermeer actually had ten minor children when he passed away at the age of forty-three. The name "Jan" was seldom used in written form and might have been a term of endearment by his family. During his burial, a family grave had to be rearranged. The remains of an infant, buried two and a half years earlier, were temporarily removed and placed back atop Vermeer's coffin.

A recently discovered register regarding the people buried in the Delft's Oude Kerk states that Vermeer's coffin was carried by fourteen pallbearers and that the church bell tolled once for him. This indicates Vermeer’s funeral would have required a significant financial expenditure. Bas van der Wulp, a member of the city archives who made the discovery, explains that such a ceremony was clearly luxurious, adding that although he had come across funerals in Delft with twenty pallbearers, these were reserved for members of the town's elite. Vermeer’s wealthy mother-in-law, Maria Thins, received a little more at her funeral, "two intervals of bells." Her troublesome son, Willem, later also received a similar funeral. Van der Wulp believes that Thins probably paid for her son -in-law's funeral thinking of eventually advancing the costs to her daughter, as they were probably not yet aware of the financial misery in which Vermeer was in at that time.

Nonetheless, on December 17, 1675, the ledger of the Delft Camer van Charitate (The Camber of Charity) laconically notes that "niet te halen," (nothing to get) to the box which was sent to the house of the deceased Vermeers. In this box, heirs customarily left the deceased's "best outer garment" or a donation to the city's poor. This fact, which is hard to square with the expensive burial ceremony, suggests that either the Vermeer family was too poor to make a donation or that Maria Thins, a staunch Catholic, had no intention of supporting the Calvinist-run charitable organization. Montias has speculated that "the failure to donate is most probably rooted in Catharina's insolvency, declared a few months later." John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 212, 216.

The Oude Kerk's church ledger noted that the artist had left, "eight children under age." In April of the same year, Catharina declared that she had been left with "eleven living children."

In the years to come, there is no documentary evidence that regarded the artist's legacy.

On 30 September 1676, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, the famed naturalist and Delft microscopist was nominated as a trustee for the Vermeer estate.

Catharina was able to survive only through the loving help of her mother, Maria Thins. The following year, she petitioned for bankruptcy.

The plea to her creditors strikes a final sad note in Vermeer's brief life. Hoping to free a sum tied up in a trust to help bring up her children, she declared:

"...during the ruinous war with France he not only was unable to sell any of his art but also, to his great detriment, was left sitting with the paintings of other masters that he was dealing in. As a result and owing to the great burden of his children having no means of his own, he lapsed into such decay and decadence, which he had so taken to heart that, as if he had fallen into a frenzy, in a day and a half he went from being healthy to being dead."

The word "decadence" is striking. "It might suggest an act of volition by the victim, such as an intensive bout of drinking that could have brought on alcohol poisoning and liver failure. On the other hand, it might simplymean a sudden physical decline: did he have a stroke? In any event, Catharina went on, Vermeer had taken his problems to heart."."Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2002), 112.

After Vermeer's death, Catharina went to great lengths to save her husband's paintings, including the masterful Art of Painting, that creditors had claimed to pay debts accumulated in the final years of the artist's life. His family struggled to settle their debt with Delft baker Hendrick van Buyten. To clear the debt, Catharina declared she had "sold" two of Vermeer's paintings to Hendrick van Buyten in February 1676, equivalent to three years' worth of bread, totaling 617 guilders and 6 stuivers. The two paintings described depict people writing a letter and someone playing an instrument, likely a lute or guitar. Four of Vermeer's works match these descriptions. In 1676, Catharina transferred these paintings as collateral for the bread debt. To reclaim them, she'd need to repay the debt in 50-guilder yearly installments. However, Catharina seemingly never reclaimed them. By the time of Van Buyten's death, he owned three Vermeer paintings, with the third possibly acquired before 1676.

Between 1681–1684 Catharina moved with her remaining eight children to Breda where she received an annuity from a family fund.

"If Vermeer's children and grandchildren slipped into oblivion soon after his death, the reputation of his art remained strong among discerning collectors. Two collectors of major importance, the baker Hendrick van Buyten and Jacob Abrahamz Dissius, kept their Vermeer paintings until the day they died. When important pictures by Vermeer were sold, as in Amsterdam in 1696 and 1699, they brought high prices."John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 212, 172.

All in all, the archival documents that have almost miraculously survived, present us with a broad, diverse pallete that can tell us much about the man behind the paintings. Vermeer was born into the middle class and married— not without some obstacles—a woman of a higher social station, which boosted his own social status. He and his wife, Catharina Bolnes, had many children, but lost several of them. As a master painter Vermeer had his glory years, which roughly coincided with the flowering of his city. However, in 1672 (the Year of Disaster) and subsequent years Delft experienced economic hardships, and these hit Johannes Vermeer hard, leading to him dying in debt.David de Haan, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Babs van Eijk, and Ingrid van der Vlis, Vermeer's Delft (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, Museum Prinsenhof Delft, 2023), 116.