Woman with a Pearl Necklace

c. 1662–1665Oil on canvas

55 x 45 cm. (21 5/8 x 17 3/4 in.)

Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

The Woman with a Pearl Necklace portrays a woman gazing into a mirror while holding two yellow ribbons that are attached to a pearl necklace she wears. Silhouetted against a white wall, she stands behind a table and chair in the corner of a sunlit room. Vermeer, in this painting, used the compositional format he followed in the Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (fig. 1) and A Woman Holding a Balance (fig. 2), but gave it a more dynamic character. In each of the other paintings Vermeer concentrated on the inward thoughts of the woman and conceived of ways to present self-contained images. Likewise, in the Woman with a Pearl Necklace he minimized the apparent physical activity of the figure, portraying her at the moment she has the ribbons pulled taut. Her thoughts may be inward, but they are expressed through her gaze, which reaches across the white wall of the room to the mirror next to the window (fig. 3). The whole space between her and the side wall of the room thus becomes activated with her presence. It is a subtle yet daring composition, one that succeeds because of Vermeer's acute sensitivity to the placement of objects and to the importance of spaces between these objects.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 46.5 x 39 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 42.5 x 38 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Fig. 1 Woman with a Pearl Necklace (detail)

Fig. 1 Woman with a Pearl Necklace (detail) c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas

55 x 45 cm. (21 5/8 x 17 3/4 in.)

Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

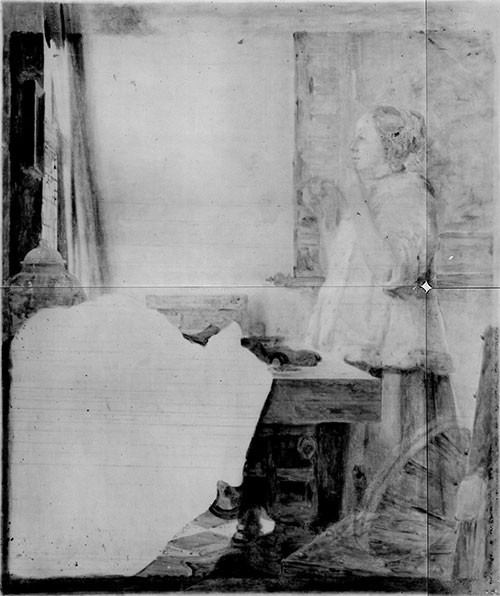

X-rays of this painting, the Woman in Blue, and A Woman Holding a Balance present further evidence of Vermeer's attention to exact compositional arrangement. All of these paintings have damages along the edges, indicating that they were once attached to slightly smaller stretchers. This smaller format may have been the one Vermeer selected, for in each instance the composition at the reduced dimension is the more successful of the two possibilities. With each of these paintings subsequent restorers, noting that the painted composition extended over the edges of the stretcher, reenlarged the format to what they thought were its original dimensions.

This phenomenon is most striking in the Woman in Blue. In this painting severe paint losses have occurred across the bottom of the composition at the level of the chair seat. Vermeer may have recognized that his composition would be stronger if he eliminated the succession of small shapes created by the legs of the chair. He may have reached this decision after painting the Woman with a Pearl Necklace, where the bottom edge of the painting aligns with the seat of the chair.

Vermeer may have used the type of stretcher seen in a 1631 painting by Jan Miense Molenaer, The Artist's Studio (fig. 4) in which strong twine, strung between the linen and nails or holes in the stretcher, attached the linen to the frame. After completing his painting, Vermeer could then have selected the optimal format for his composition. He would have subsequently placed the linen on a conventional stretcher. In the process of reducing his composition, however, painted tacking margins would have remained.

Jan Miense Molenaer

1631

Oil on canvas, 86 x 127 cm.

Staatliche Museen, Berlin

The Map of the Netherlands that Vermeer Painted Out

Technical examination of the painting reveals significant pentimenti, indicating many careful refinements to the composition. Neutron autoradiography (fig. 5) shows that Vermeer originally included a musical instrument, probably a lute, on the chair in the foreground. An even more startling discovery, however, is that Vermeer originally planned to include a wall map, similar to that in The Art of Painting, behind the woman on the rear wall. Finally, this examination technique revealed that the dark cloth on the table covered less of the tile floor under the table.

The change in the shape of the cloth eliminated much of the light area beneath the table, leaving only the shape of one table leg to orient the viewer. As a result of this alteration the viewer's attention is focused more exclusively on the light-filled space above. While the elimination of the map and lute also simplifies the composition, it may also be related to thematic reasons. The map, representing the physical world, and the musical instrument, referring to sensual love, would have given a context for interpreting the mirror and the pearls negatively rather than positively. Indeed, the sensual, earthy connotations are similar to those associated with images of "Vrouw Wereld" (Lady World: the allegorical figure of worldly nature). By removing the map and lute he transformed the character of the image into a poetic one evoking the ideals of a life lived with purity and truth.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 55 x 45 cm.

Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

The Woman with a pearl necklace, now in Berlin, is one of the largest of Vermeer's small, single-figure paintings, having a few centimeters more height than the National Gallery paintings, for example. It is probably the work listed in the 1696 inventory as "a young lady adorning herself, very beautiful." Yet despite this and its size it was priced at only 63 guilders, in contrast with the smaller but in many ways similar Woman holding a balance.

Even within the restricted range and constant repetitions of Vermeer's pictorial topography, these two most narrowly coincide. Only the Woman tuning a lute, in the Metropolitan, New York, which is on the scale of the Woman with a pearl necklace, might be compared with them. All three show the window butted against the plain rear wall; the leading, where it is visible, is the clear version of the heraldic pattern seen in the other Berlin painting, the Glass of wine. All three have a similar heavy table placed against the window wall, slightly to the fore of the window. Two further similarities are shared by the Woman with a pearl necklace and Woman holding a balance: the carpet covering the table is rucked back to form an irregular range of ridges and valleys, at once exposing the bare table-top and obscuring the objects on it, and beside the window hangs a similar mirror. Oddly, perhaps, the mirror into which the woman with a pearl necklace is looking is smaller than that in the Woman holding a balance. In reproduction the two appear to make a pair not dissimilar to the two in the National Gallery, London. In reality, the difference in size means that they cannot have been intended as pendants in the strict sense. Nevertheless, as they both were, in all probability, bought directly from the artist by his patron, Van Ruijven, it may be that the second piece (whichever that might have been) was painted in the knowledge that the two works would remain in the one collection and be seen in a similar light.

Like the Woman holding a balance, the Woman with a pearl necklace recalls earlier images. Most similar is that of Superbia, the sin of pride.

In his table of the Seven Deadly Sins, now in the Prado, Hieronyrnous Bosch had exemplified Pride (fig. 6) by a bourgeois woman admiring herself in a glass held up by a devil; and behind her is an open jewel box. The objects on the table in Vermeer's painting are obscured by shadow and their overlapping contours but, in addition to the large Chinese jar, they include a powder brush and comb. (However, the rectangle rising above the level of the table is not a jewel box, as in the Woman holding a balance, but, as the shadow on the wall reveals, the back of a chair.) In a closely allied image, many of Vermeer's contemporaries represented a young woman rising from her bed and dressing before a glass to evoke the traditional motif of the goddess of love, Venus, at her toilet. This could be equated with another sin, that of Luxuria or lust. Again, it could be a vanitas image, a reflection on the ephemerality of youthful beauty, the brevity of human life and the inevitability of death. But mirrors had many meanings in Netherlandish painting. They could reflect Truth, as it has been claimed far the mirror in the Woman holding a balance. It was for this reason that Prudence regards herself in a glass, to know herself more thoroughly. Sight, one of the five senses, also has a looking glass as one of her attributes.

Hieronymus Bosch

1485

Oil on wood, 120 × 150 cm.

Museo del Prado, Madrid

At first sight, the Woman with a pearl necklace appears unlikely to exemplify Truth, Prudence or the sense of Sight. Truth should be naked or, at the very least, have a balance, too, as in the Washington painting. Prudence would have a serpent (is the unexplained shadow beneath the table of the Washington painting a serpent?) Sight would be accompanied by the sharp-eyed eagle or, more domestically, a cat. Faced by an image of a young woman adorning herself before a glass without further attributes, a contemporary would recognize the sins of Pride and Lust, or, responding to the beauty of this young woman, would reflect on the brevity of life and the vanity of worldly desires (fig. 7).

Nicolas Tournier

104 x 84 cm.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

To see the painting in this light, however, is to miss its singular distinction. In the tradition of images of vice and folly, the sinner is heedlessly, or even vaingloriously, engaged in, committed to, vain pursuits. It is the viewer alone who stands pack and considers the consequences of those blind passions. But Vermeer's young woman stares at her own outward beauty visible to herself alone in the glass, and just as the glass reflects her face so, manifestly, she reflects on it. As in the Rijksmuseum Letter- reader and the Washington Woman holding a balance, here, too, a simple profile establishes for the viewer a sense both of intimacy and of distance, of individuality and universality. This most abstract of painters, concerned with the appearance of light reflected from surfaces, nevertheless leaves no room for doubt that the young woman appears as she does because.the rapid and deft movements with which she had placed the pearls around her throat, movements that reflected her innocent self-satisfaction, have been stilled as more profound and sobering reflections cross her mind. There can be no doubt, that is, if the viewer will contemplate this image as the young woman regards her own. It is an image that leads the mind from vanity to self-knowledge and truth through the sense of sight by physical and mental reflection.

One can hardly imagine that such a sympathetic, almost loving treatment of the subject could be invented, let alone learned. But since The Letter Reader in Dresden Vermeer's sensitivity to feminine behaviour (which goes back to the beginning) had taken something close to this form, which in both style and subject owed a great deal to Gerard ter Borch (fig. 8). Other models have been mentioned, such as a painting by Frans van Mieris (fig. 9) that is thought to date from about 1662 and a panel of about 1645 (fig. 10) by the fashionable Flemish artist Erasmus Quellinus the Younger. The paintings by Quellinus and Van Mieris are closer in composition to Vermeer's picture than is Ter Borch's panel but his interpretation is much closer in spirit. In each possible prototype a maid is present, in one way or another remarking (in Quellinus, almost winking at) the woman's vanity. The theme went back at least as far as Bosch's Tabletop of the Seven Deadly Sins and in the seventeenth century was often illustrated in emblem books and in a broad range of genre paintings. In Jacob Cats's Spiegel vanden ouden en nieuwen tijdt (The Hague 1632) a woman fretfully combs her hair in front of a mirror, and the subscriptio explains that one must also comb 'what is hidden inside' to achieve a 'pure foundation'. The mirror itself is the main bearer of meaning in images of women at their toilet by Roemer Visscher (1614), an elaborate engraving by Jacques de Gheyn (fig. 12) and paintings by Adriaen van de Venne (fig. 13) (where the mirror is supported by a fool), Paulus Moreelse (fig. 11) and many other artists, including contemporary Flemish and French as well as Dutch painters.

Gerard ter Borch

c. 1650-51 Oil on wood, 47.5 x 34.5 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Frans van Mieris the Elder

1661 - 1663

Oil on panel, 30 x 23 cm.

Berlin State Museums, Gemäldegalerie

Erasmus Quillinus the Younger

c. 1645–1650

Oil on wood. 38.5 x 32.5 cm.

Formerly collection of Joseph Fievez

Paulus Moreelse

1627

Oil on canvas, 105.5 x 83 cm.

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Jacques de Gheyn (II)

c. 1569–1596

25.9 x 18.3 cm.

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Adriaen Pietersz. van de Venne

c. 1630

Oil, grisaille painting, 36 x 32 cm.

Hermitage, St. Petersburg

This tradition was so familiar by about 1649–1650, when Ter Borch depicted a pretty model (his half-sister Gesina) in front of a mirror, that no other motif was needed in order to allude to the idea of vanity [location unknown], where emblems by Cats and Visscher are compared). That same familiarity with the conventional meaning allowed Ter Borch to reinterpret the theme in a manner that reveals something distinctive about his own personality and also suggests a shifting sensibility in Dutch culture at the time. In many pictures of women alone, or virtually alone, or with people they may or may not admire, their expressions and gestures, their character, their normal emotions and behaviour are Ter Borch's main concern, as if he were recording, for himself, his own private world (which to some extent he was). No contemporary artist equalled Ter Borch in this regard, at least in his chosen genre (of course, Rembrandt portraits and history pictures come to mind). However, Vermeer, with his very different temperament, provides a parallel in several paintings, of which the Woman with a Pearl Necklace is one of the most remarkable.