The Lacemaker

c. 1669–1671Oil on canvas on panel

24.5 x 21 cm. (9 5/8 x 8 1/4 in.)

Musée du Louvre, Paris

In this, one of Vermeer's most beloved paintings, a young bends over her work, tautly holding the bobbins and pins essential for her craft (fig. 1). Sitting very close to the foreground, behind a lacemaking table and a large blue sewing cushion, Vermeer's devotes every ounce of her attention to this one activity, while the viewer peers in with equal intensity, mesmerized by her adeptness and artistic skill.

The viewer's emotional engagement is unique in Vermeer's oeuvre. The painting's intimacy, derived from its small scale, personal subject matter, and informal composition, draws the viewer to it, challenging the barrier between image and reality; Vermeer suggests the total absorption in her task through her constricted pose and the bright yellow of her bodice, an active and psychologically intense color. Even her hairstyle conveys something or her physical and psychological state of being, for it is likewise both tightly constrained and rhythmically flowing. Finally, the crisp accents of light that illuminate her forehead and fingers emphasize the precision and clarity of vision required by this demanding craft.

c. 1669–1671

Oil on canvas on panel

24.5 x 21 cm. (9 5/8 x 8 1/4 in.)

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Vermeer further engages the viewer by simulating an optical experience that occurs when observing a scene closely different depths of field. In one of his most striking passages (fig. 2), Vermeer softly and fluidly applies red and white strokes of paint to create the illusion of diffused, colored threads flowing from the partially opened sewing cushion. Their liquid forms spill out onto the equally suggestive floral patterns of the table covering. By recreating this optical phenomenon, where forms situated nearest the ere appear diffused and unfocused, Vermeer pulls the viewer close the picture plane. At the same time, these diffused forms encourage the eye to pass over the foreground and to focus on the clearly defined middleground, consisting of the lace maker herself. A soft ringlet silhouetted against the white wall marks a more distant plane beyond the field of focus. Indeed, the threads and ringlet curl serve as a visual foil to the taut threads of the bobbins, thereby setting the figures 's activity apart from her surroundings.

Although Vermeer remained remarkably sensitive to light and color throughout his career, he frequently altered their natural effects for compositional reasons. Nevertheless, the abstract shape and texture of the red and white threads in the foreground of this painting are without parallel, the closest equivalent being the lion-head finial in the right foreground of The Girl with the Red Hat. As with the diffused, almost. fragmented finial, the optical effect of the threads certainly derives from a camera obscura image. Indeed, the informality of this tightly framed composition, so different from the more traditional representations of s by Nicolaes Maes (1634–1693) and Caspar Netscher 1639–1684), may also have been stimulated by the use of this device.

Although the small scale of the painting, the informal pose of the, and the clearly articulated differences in depth of field support the hypothesis that the artist viewed the scene through a camera obscura, Vermeer would not have painted on top of an image projected onto the canvas by this optical device. As in The Girl with the Red Hat, the subtleties of his composition preclude such a possibility.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1669–1671

Oil on canvas on panel, 24.5 x 21 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Within Dutch literary and pictorial traditions, the girl's industriousness would have indicated domestic virtue, a theme Vermeer reinforced through the small book with parchment cover and dark ties on the table beside her. Although the book has no identifying features, it almost certainly represents a prayer book or small Bible. Nevertheless, such moralizing concerns seem secondary in this small but dynamic image. The concerns here are far more with the craft of lacemaking, and, even more broadly, with the human capacity to create.

The method, which from the time of The Music Lesson onward has been progressively clarified and crystallized, here reaches the culmination, jewel-like, immaculate and baffling, with which we are familiar. The result is a style whose very detachment conveys, resolved at last, the delicate tension of feeling which is the burden of the painter's work. The subject, the making of lace, had provided a favourite theme of all Vermeer's predecessors in the genre school. If he was particularly indebted to any one of them it was to Nicolaes Maes; in drawings (fig. 3) of the motif by Maes dating from perhaps ten years earlier we find a similar arrangement, giving just such a value to the disposition of fingers and the form of the foreshortened head. Without such precedents the boldness of Vermeer's treatment of the subject here might indeed seem a little unexpected. Vermeer translates the suggestion into terms agreeable to his temperament. The bowed, preoccupied pose, which is of all themes from the Letter Reader onwards the most congenial to him, here reveals its peculiar advantages. The bends intently over her pursuit, unaware of any other happening. It is perhaps the fact that she is so absorbed, enclosed in her own lacy world, that allows us to approach her so close.

Nicolaes Maes

c. 1654–1655

drawing in red chalk, 14.1 x 11.8 cm.

Boijmans Museum, Rotterdam

The woman's dedication is conveyed not only by her pose but also by the picture's design. The brightest light and colours and, as one might expect, various contours focus attention on the lacemaker's work. The lines of the sewing cushion lead into the figures forearm, in a rhythm reminiscent of several in earlier compositions with objects spread across tabletops. The area of tile woman's face and hands is unobtrusively surrounded by curving forms such as the dangling curl, the parted hair, the near shoulder and sleeve, and the red threads. A similar integrity of design was often achieved by Ter Borch, but without this degree of coherence and intensity. If one compares The Lacemaker with The Milkmaid), at least two aspects appear distinctive of Vermeer. First, the forms are contained within a simple shape that on a less intimate scale would seem monumental. Second, the design's centre of focus itself represents an act of concentration. Like many figures in Vermeer's oeuvre, and like the painter himself, these figures lose themselves in what they do.

Nicolaes Maes

c. 1655

Oil on panel, 38.8 x 35.9 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

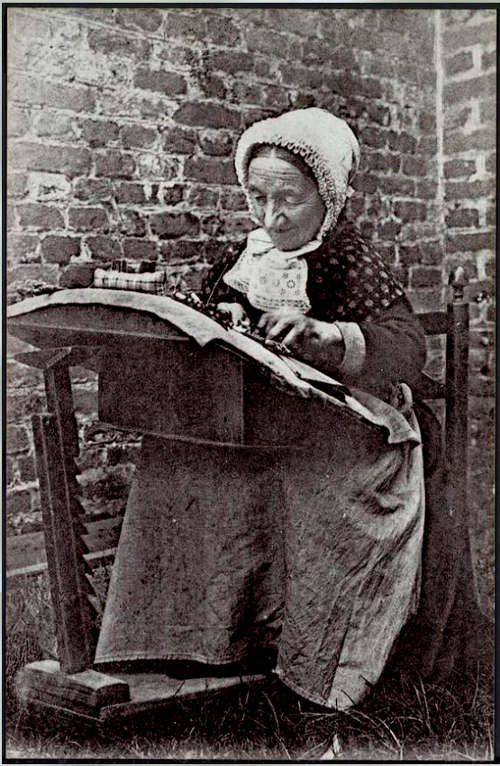

The precise form of stand in The Lacemaker is not seen in other seventeenth-century sources and no early examples survive. However, the general type is known from patternbooks such as Nicolas Bassée's New Modelbuch (1568), where one of the illustrations (featuring architectural details and a dog adopted from Dürer 's Saint Jerome in His Study) shows a stand (fig. 5) comprised of a single post and a tilted platform with a shelf at the front. A smaller version of this type of stand supports the bobbin box used by Maes's elderly lacemaker (fig. 4); the post, which features a series of evenly spaced holes where a peg can be inserted to adjust the hight of the platform, appears to be centred under the platform and has a blocky base (similar stand can be seen in fig. 6 & 7). The stand in Vermeer's painting is a fancier model: the light platform, with scalloped carving on the underside, tapers towards the finial of the post. Peg holes allow the height of the platform to be adjusted. The wood panel below the platform has square holes and a scalloped foot or shelf at the bottom. It is evidently part of the stand and probably adjustable, but its precise purpose is now unclear.

New Modelbuch, von Allerhandt Art Nehens und Stickens (A Lace Guide for Makers and Collectors)

Nicolas Bassée

Frankfurt am Main, 1568

Embroidery was, traditionally, the occupation shown in representations of the Education of the Virgin. In seventeenth-century Dutch paintings, it appears to represent the occupation of the virtuous young woman, a virgin, presumably. It is lacemaking or embroidery that is put to one side when a love letter arrives, as has been seen in the pictures of lave letters by Metsu and Vermeer. In the well-known painting of a young girl by Caspar Netscher (fig. 8) in the Wallace Collection, the young woman wearing simple, even poor, clothes and shown clearly in profile against a wall is surrounded by a curious array of objects. The broom, the discarded shoes that are not, it seems, her own and the mussel shells are more familiar in brothel scenes. The shellfish are provokers of lust, the shoes are those cast off before lovers get into bed and the broom is that used by the whore to beat out the Prodigal Sons once their inheritances are spent. In the case of Netscher's, it seems that virtue may be under threat. But may any of this apply to Vermeer's diligent young woman?

Caspar Netscher

1664

Oil on canvas, 33 x 27 cm.

Wallace Collection, London

Her diligence preserves her virtue: of that there is little doubt. Within easy reach of her right hand lies a book which is, surely, the Book, the Bible. But what is the work box doing there, so prominently placed; why should those threads of white and scarlet spill from it so copiously? The work box was known in Vermeer's day as naaikussen which is, literally, a needle cushion. But naaien means, vulgarly and metaphorically, to copulate, and though the noun kussen means cushion, the verb kussen means to kiss. The threads that gush from the gape in this swollen naaikussen evoke the blood red and milk white spilling from the womb that precede the birth of a child.