The Allegory of Faith

c. 1670–1674Oil on canvas

114.3 x 88.9 cm. (45 x 35 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This unusual Vermeer represents an allegory of Catholic faith. The figure of is depicted in a theatrical pose, clutching her hand to her breast, her eyes gazing upwards and her right foot resting on a globe. She is loosely based on the symbolic representation from Ripa's Iconologia (fig. 1) in which Faith is described as 'a seated lady...her feet resting on Earth'. Vermeer's picture is somewhat contrived, and painted in the very polished style that was popularized by the 'fine' painters of Leiden , such as Dou and Van Mieris.

from Cesare Ripa

Iconologia

1644, Amsterdam

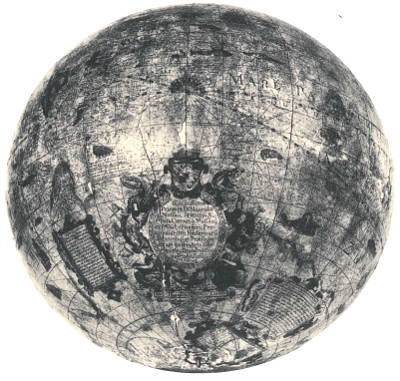

On the altar-like table of Allegory Faith lie a chalice and an open Bible. There is also a crucifix (fig. 2), quite possibly the 'ebony wood crucifix' listed in the inventory of movable goods drawn up after Vermeer's death. The terrestrial globe (fig. 3) is the same as that depicted in The Geographer, by Hondius (fig. 4), and Faith rests her foot on the continent of Asia. On the floor lies a bitten apple, representing sin. The twisted serpent has been crushed by a stone and blood spurts from its mouth, a fate which symbolizes the victory of good over evil.

The painting on the back wall is a slightly simplified version of the Crucifixion by Jacob Jordaens, a version of which survives in Antwerp. Vermeer has omitted both the man on the ladder and Mary Magdalene at the feet of Christ, presumably to avoid undue distraction from the figure of Faith. Vermeer's family may have owned the Jordaens, or a copy of it, since the 1676 inventory includes a 'large painting representing Christ on the Cross'.

The Art of Painting must have served as a prototype for Allegory of Faith, which was probably commissioned by a Catholic patron who had admired the earlier work. Both allegories are set in the same room, with its beamed ceiling, marble floor tiles and tapestry curtain. It is interesting that although Allegory of Faith was obviously intended for a Catholic patron, it was soon acquired by a Protestant collector. In 1699 it was sold by the Protestant banker Herman van Swoll, who had presumably obtained it as an example of a "fine" painting.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 114.3 x 88.9 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 114.3 x 88.9 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig. 4 Terrestrial Globe

Fig. 4 Terrestrial GlobeJodocus Hondius

1618,

Germanisches National

Museum, Nuremberg

The Terrestial Globe

A number of scholars have remarked on the similarity in composition between The Art of Painting and the Allegory of Faith, painted eight or nine years later: the tapestry framing the left side of both pictures; the distance of the painter from the scene which allows him to show both floors and rafters from much the same perspective; the globe which plays the same role in the Allegory of Faith as the chandelier in The Art of Painting. It is quite possible that someone saw the earlier picture in the artist's studio and ordered a Catholic allegory with a similar composition. Vermeer's patronage, in 'this case, may have come from the Jesuits next door or from other pious Catholics. The serpent, symbol of Protestant heresy, spits blood. It is crushed by a slab, which stands for the stone on which Christ ordered Peter, alias Simon, to erect His Church and found the papacy. The heretics may not actually have persecuted the "papists" in Delft, but they hemmed them in and forced them to worship in secret. They would have been shocked by the Allegory of Faith, which could only have hung in a Catholic chapel or in a devout Catholic home.

Adriaen van der Werff

1699

Oil on canvas on panel, 81 x 65.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede

Its similarity to the ever popular Art of Painting notwithstanding, the Allegory has not been much admired of late. The pose of the figure of Faith is too histrionic, the manner of painting too glossy and slick for the modern viewer. And yet it holds up very well against the works of other Dutch painters of the period—Frans van Mieris, Eglon van der Neer, and, later, Adriaen van der Werff (fig. 5)—who favored such a cold classical style. Vermeer, in the Catholic ghetto of a town that was rapidly reverting to its sixteenth-century provincialism, had to emulate the "fine-painting" fashion of Leyden and Amsterdam, the more dynamic cities of Holland, if he wanted to transcend the limitations imposed by his physical isolation.

The Painting on the Back Wall

The painting on the back wall is a slightly simplified version of the Crucifixion by Jacob Jordaens, a version of which survives in Antwerp (fig. 6). Vermeer has omitted both the man on the ladder and Mary Magdalene at the feet of Christ, presumably to avoid undue distraction from the figure of Faith. Vermeer's family may have owned the Jordaens, or a copy of it, since the 1676 inventory includes a 'large painting representing Christ on the Cross.'

:

Martin Bailey, Vermeer, London, 1995

Jacob Jordaens

c. 1620

Private collection, Antwerp