Even though few archival records which regard Vermeer directly have survived, historians have deduced a relatively clear picture of both the artist's life and artistic stature in his own time. In 1952, the Dutch art historian P.T.A. SwillenP. T. A. Swillens, Johannes Vermeer: Painter of Delft 1632–1675 (Utrecht: Spectrum, 1950). provided the first adequate picture of Vermeer's life (Johannes Vermeer Painter of Delft: 1632–1675). However, an important part of what we now know is owed to John Michael Montias, the late American economist turned Vermeer biographer. For over ten years Montias patiently transcribed, translated, and pieced together over 454 legal depositions, wills, deeds, warrants, inventories, and promissory notes to form an acceptable portrait of one of the greatest painters of the seventeenth century and his extended family. Curiously, Montias came to Vermeer sideways. He discovered that research on Vermeer's life had not been exhaustive. The result of Montias'study is the eminently readable Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (1989).

Click here to read an Essential Vermeer Interview with the late Prof. Montias.

- Grandparents

- Parents

- Birth & Living in Delft

- Guild of Saint Luke & Training

- Who was Vermeer's Master?

- Marriage

- Early Works

Grandparents

When Vermeer was born in Delft, the city was already more than 350 years old. In those times Delft was a prosperous, albeit conservative, Dutch town located in the south of the United Provinces, within the province of Holland. Delft had survived devastating fires and various bouts with the plague. "Its wealth was based on its thriving faience factories, tapestry-weaving ateliers and breweries. Moreover, it was also a city with a long and distinguished past. Its strong fortifications, city walls, and medieval gates protected the city for more than three centuries and had provided refuge for William the Silent, Prince of Orange during the Dutch revolt against Spanish Habsburg control. Although the court and seat of government moved to The Hague at the end of the sixteenth century, Delft continued to enjoy a special status."John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 172. The city was not only the home of the famous School of Delft of painting, it was a thriving center for the decorative arts: tapestry, silver, and faience, or Delft Blue.

Many of Delft's wealthiet citizens, who lived in sumptuous houses along the city's main canal, the Oude Delft, had made their fortunes investing in the East and West India (VOC) trade. More than 300 Delft households were worth more than 20,000 guilders. A carpenter or a mason might earn 500 guilders a year if his health was good. The city, which is articulated within a network of perpendicular canals, draws its name from the Dutch word delven (digging). Although Delft did not have a harbor at the mouth of a river like Bruges, Antwerp or Amsterdam, it was nonetheless connected to the sea by the inland harbor, Delfshaven a few miles away.

Johannes Vermeer was the second child and only son of Reynier Jansz. (c. 1591–1652)In documents, Vermeer’s father mostly called himself" Van der Minne," after his stepfather, or Vos (fox), as the animal also depicted on the signboard of his inn—possibly a nod to the medieval animal tale "Vanden vos Reynaerde" or Reynard the Fox, because of his own first name. and his wife Dignum Balthazars, also known as Digna Baltens (c. 1595–1670). Reynier's parents were the tailor Jan Reyersz. (d. 1597), who lived on the Beestenmarkt in a house called Nassau, a block south of the Nieuwe Kerk, and Cornelia (Neeltge) Goris (c. 1567–1627).

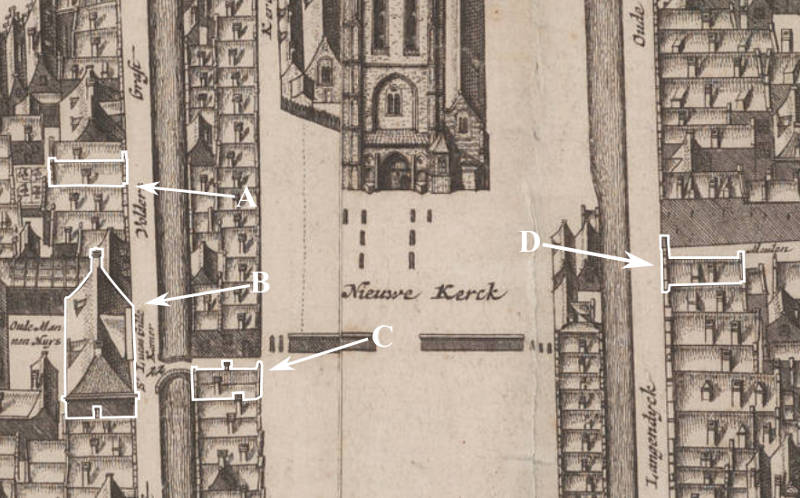

A. Flying Fox (Vermeer's presumed birthplace and inn of his father)

B. The Delft Guild of St. Luke (professional organization of artists and artisans)

C. Mechelen (a large tavern on the Market Square rented by his father where Vermeer and his family lived after the Flying Fox

D. Groot Serpent (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

E. Trapmolen (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

Neeltge lived on Voldersgracht; Fullers' Canal, in the house called In de Bruynvisch (In the porpoise). She was active as uijtdraegster, or second-hand goods dealer, liquidating estates of deceased people.A "uijtdraegster" (also spelled "uitdraegster") was a specific type of female street vendor in the Netherlands, particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries. These women were typically older and often widowed, and they earned a living by selling second-hand goods, such as clothes, household items, and sometimes food, that they collected from wealthier households. The term "uijtdraegster" is derived from the Dutch word "uitdragen," meaning "to carry out" or "to peddle," reflecting their role in carrying goods through the streets to sell. These women were a common sight in Dutch cities, and their role was crucial in the recycling of goods in the urban economy of the time. While they often occupied a lower social status, their work was an essential part of the community's informal economy, allowing goods to be reused and circulated among different social classes. The image of the uijtdraegster has also been depicted in Dutch art, representing the everyday life and social dynamics of the period. As paintings were frequently part of estates, Neeltge's dealings may have propitiated Reynier's future interest in second-hand paintings.Walter Liedtke, Vermeer: The Complete Paintings (New Haven and London: Harry N. Abrams, 2008), 71. Jan and Neeltge lived in the Beestenmarkt, the Cattle Market. From 1595 to 1972, Beestenmarkt was the site of the noisy livestock market held weekly in Delft. Like most of the people who lived there, both were illiterate. Though Reynier and Digna were not particularly wealthy, they were not penniless. An estate inventory drawn up in December 1623 reveals that they owned a small collection of paintings, including some still lifes, a few history paintings, portraits, and genre scenes.Among them several portraits of members of the stadholder’s family draw particular attention. The likenesses of "Zijne Excelentye ende prins Henrik" (His Excellency and Prince Hendrik), or Stadholder Maurits and his half-brother Frederik Hendrik, and "de prins met de princesse" (the prince with the princess), presumably William of Orange and Louise de Coligny, underscore the Orangist leaning of the Protestant Reynier and Digna in the turbulent days after the Twelve Years’ Truce in the Eighty Years’ War.

After Jan's death in 1597, Neeltge married Claes Corstiaensz van der Minne (c. 1548–1618).. Claes was a tavern keeper and professional musician who lived at De Drie Hamers in Beestenmarkt. Claes owned a lute, a trombone, a shawm, two violins, and a "cornet." After Jan's death Neeltge was left with three young children. Claes had also been previously married and had a teenage son. His father was a barber and a singer/musician who arrived in Delft sometime before 1553.

Balthasar Gerrits (c. 1573–c. 1630), the father of Vermeer's mother, resided in Antwerp and was an expert in metalwork and coin-making. When Spanish troops occupied his hometown Antwerp, he moved to Amsterdam. In 1620, his son Balthens was arrested for a counterfeiting scam in The Hague, where he and his father had cut dies in order to forge counterfeit coins.John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 17. Both were imprisoned but granted some leeway in the trial because they may have been asked to counterfeit coins in order to create cash for a newly founded Calvinist ally in German territory near the Netherlands.

Members of Balthasar's family testified as witnesses for both father and son, but Balthasar was found guilty and imprisoned in Antwerp during these hearings. His son Balthens was also arrested and put in jail. Two of their accomplices were convicted and beheaded. After Balthasar gave authorities a full confession and the names of the remaining members of the counterfeit gang, he was freed. In a document of 1627, Balthasar was described "an artful master of clockmaking and other wonderful inventions." In 1631, he went to Delft, where he was active in metalwork and clockwork.

Parents

Reynier Jansz., Vermeer's father and one of Neeltge's three children born before her first husband's death, was born in his father's house.

In 1611, Reynier, who was then about twenty years old, went to Amsterdam to train as a caffawercker (silkworker). Caffa was a kind of fine satin woven with patterns or pictorial motifs widely used for clothes, curtains, and furniture-covering. Some scholars have speculated that Vermeer's predilections for this material may have been related to a childhood remembrance, although luxurious satin garments were one of the principal selling points of the elite interior and portrait markets. At the end of his apprenticeship in 1615, Reynier married Digna, a native of Antwerp, in Amsterdam. The ceremony was officiated by the famous Calvinist preacher, Jacobus Triglandius on July 19. When Digna signed the marriage register to the effect that the couple was free of blood ties, she signed with an "X." She later learned to sign her name. Shortly after their marriage the couple settled in Delft. Vermeer's sister, Gertruy, was born in March of 1620, 12 years earlier than Johannes.

In 1623, Reynier's and Digna's movable goods were appraised and valued at 693 guilders. Their paintings, which included four princely portraits, a few pictures of the Old Testament, a brothel scene (bordeeltje) and a painting of "an Italian piper," were worth 53 guilders. Vermeer's uncle Anthony had already adopted the surname "Vermeer" by 1625 while the artist's father is mentioned as Reynier Jansz Vermeer in 1640. Vermeer's family background would be described today as lower-middle-class.

Between 1629 and 1631, Reynier was described in several documents as an innkeeper. Perhaps encouraged by his association with the art-collecting notary Willem de Langue (1599–1656), Reynier registered with the Delft Guild of Saint Luke as an art dealer on October 13, 1631. The paintings in which Reynier dealt may have sparked his son an interest in painting. Likely, Reynier probably knew most of Delft's artists and sold some of their works in his inn. Documents link his name with local painters Pieter Groenewegen (1590/1600–1658), Balthasar van der Ast (1593/94–1657) and Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674), the latter of which was one of the city's chief artists as well as a friend of Vermeer's family. Indeed, at the time inn-keeping and paintings went together, since outside their studios and annual fairs, painters had few opportunities to display their works.

Birth and Life in Delft

Vermeer was baptized on October 31, 1632, in the Reformed Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) and was raised a Protestant. His Christian name "Johannes" (or Joannis or Johannis) was favored over the prosaic "Jan" by Catholics and upper-class Protestants. Regarding his first name, Montias argued that the painter himself never used the name Jan, but according to recent research, "this statement relies only on Vermeer’s signature in official documents and on his paintings, in which he presented himself as 'Johannis' or 'Joannes.' The American Vermeer expert here disregarded the above-mentioned notarial deed of 5 April. It is noteworthy that Catharina Bolnes (1631–1687) and Johannes Vermeer are described in this document as 'Trijntgen Reijniers' and 'Jan Reyniersz.' Both in their twenties, they were apparently called Trijntje and Jan by acquaintances in everyday interaction and used the formal names."Pieter Roelofs,"Johannes Vermeer (Delft 1632–1675) Modestly Masterfu" in VERMEER, ed. Pieter Roelofs & Gregor Weber, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023, 30. At that time Reynier established himself in De Vliegende Vos (The Flying Fox) in Voldersgracht, a street which bordered on one of Delft's many canals, a minute's walk from the massive Nieuwe Kerk (fig. 2) on Markt (Market Square) (fig. 1).

Before he called himself Vermeer, Reynier Jansz. took the name Vos, which means fox in Dutch. Everyone in Holland knew of "Reynaerd de Vos," the Romance of Reynard the Fox.Romance of Reynard the Fox refers to a collection of medieval European folktales and fables centering on Reynard (or "Renart" in French, "Reineke" or "Reynke" in German, and "Reinaert" in Dutch), a cunning red fox. These stories portray Reynard as a trickster who often finds himself at odds with other anthropomorphic animals, especially the wolf named Isengrim and the king, Noble the Lion. Reynard's adventures are a blend of satire, allegory, and social commentary, and they were a popular literary subject from the 12th to 15th centuries. The name Reynier became confused in people's minds with Reynaerd, and the combination Reynier Jansz. Vos developed naturally from it.John Michael Montias,"Chronicle of a Delft Family," in Vermeer, edited by Albert Blankert, Gilles Aillaud, and John Michael Montias (Woodstock and New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2007), 26.

In the seventeenth century, Delft's Markt was an important commercial center where fine silks and velvets as well as common linens and wools were traded. "Growing up in the Voldersgracht, in a small inn, was to be from the start close to the heart of Delft. From his early years he was aware of a constant flow of people, of talk that was genial, humorous, now and then angry, of tobacco smoke and fireplace smoke, of doors and windows closed against the winter cold or open in summer when the sun bounced off the surface of the little canal, and the backs of the houses on the north side of the Market Place threw long shadows; he had a private world, one suspects, in which the sun and shadow were his best companions."Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2002), 44.

The area around the Voldersgracht in Delft was much more distinguished than the Beestenmarkt. Near the Flying Fox lived the respected Pastor Taurinus, Cornelis van Schagen, a well-to-do cloth merchant, and the Catholic portrait artist Cornelis Daemen Rietwijck (c. 1590–1660), who held a drawing academy and also taught mathematics and other subjects. Rietwijck's drawing school was located a few houses down from De Vliegende Vos. At this school, young students were not only instructed in the fundamental principles of painting, which encompassed drawing from prints, drawings, and plaster models, but they also received a basic education in subjects like mathematics. His personal library contained a variety of books, including devotional literature, travel accounts, historical descriptions; and a copy of Karel van Mander's 1604 work Het schilderboeck (The Book of Painters), which was considered the essential reference for painters during that era, akin to a Bible for painters.Pieter Roelofs and Gregor Weber, VERMEER (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023), 28.

From what can be deduced from Renyier's economic rise and legal depositions, he was a hardworking and trustworthy man.

Montias believed that the Flying Fox was located "two houses east of the Oude Mannenhuis (Old Men's Hom)," which would correspond to the present-day civic number 23, Voldersgracht. From 1620–1640 changes had been made just in the row of houses at 2–27. Some buildings were probably joined and then split into still other lots. Consensus has it that the most probable location of the Flying Fox is at 25 or 26. The scholar Kees Kaldenbach pinpoints the location at 26.

Vermeer spent his childhood in a large house located on the Markt in the very heart of Delft.. Reynier bought the building with 200 guilders in cash and two mortgages, one for 2,100 guilders and another for 400 guilders. Such a sizable sum indicates that Reynier was considered able to meet his debts. Reynier and his family moved into their new living quarters in the spring of 1641.

The ground floor of the new house was an inn, called Mechelen. The back side of the building dropped straight down into the waters of the Voldersgracht. The façade of the Guild of Saint Luke could be seen from a back window just across the canal. Along the right-hand side of Mechelen ran a narrow alley, the Old Mens' Alley, which no longer exits, leading from Markt to a small bridge and up to the front door of the Guild. An effigy of the Mechelen's front side (fig. 3) is preserved in an etching by Leonard Schenkmade, after a drawing by Abraham Rademaker. A drawing by Gerrit Lambert (fig. 4), instead, shows the alley which leads to the façade of the Guild. Around 1631, Reynier, at around forty years of age, registered with the Guild as an art-dealer. Due to the high demand for paintings, intermediaries emerged in the market, and Reynier's proximity to many painters and potential art-buying customers might have influenced his entry into the art trade.Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2002), 43.

Leonard Schenk after a drawing by Abraham Rademaker

c. 1730

Engraving, 57 x 98 cm.

Gemeenarchief, Delft

Gerrit Lambert

1820

Graphite, pen and brown ink, brush and gray ink, 24.9 x 19.3 cm.

Gemeenarchief, Delft

View of Old Men's Alley with Mechelen on the left, the building at the end of the alley is the Guildhouse of Saint Luke.

Judging from the etching, Mechelen must have been quite large, large enough to accommodate an inn, Reynier's caffa production and living quarters for his family of four. Mechelen was demolished in 1885 to make way for fire-prevention equipment, resulting in the present vacant lot next to Markt number 52. Therefore, the plaque that commemorates Vermeer's birthplace is incorrect.

When Reynier died in October 1652, the family gave no money (as was the custom) to the Kamer van Charitate (Chamber of Charity). Fourteen months later, Johannes would become a member of the Delft Guild of Saint Luke. The young painter probably helped his mother and older sister run the inn, which, however, may not have been a very prosperous business. Digna was still paying off the mortgages when she attempted in vain to auction it off in 1669.

On October 12,1654, about 30 tons of gunpowder, which had been stored in barrels in a former Clarissen convent in the Doelenkwartier district, exploded. The explosion, known as the Delfts Donderslag (Delft Thunderclap), killed over a hundred people and maimed thousands. Carel Fabritius (1622–1654), Rembrandt's most gifted pupil, died while he was at his easel painting a portrait. Years later, Egbert van der Poel (1621–1664) painted several pictures of Delft showing the devastation. Except, perhaps, for the iron braces cemented to red brick façade of the medieval building portrayed in Vermeer's Little Street, there is no evidence of the traumatic event in Vermeer's paintings.

Nothing is known of Vermeer's childhood, but he must have served his apprenticeship beginning somewhere in the 1640s when he was still an adolescent.

Although the initial epidemics of the plague may not have been as catastrophic in the Netherlands as they were in many other parts of Europe, Delft was stricken several times before and during the artist's lifetime. During the plague putbreaks of 1624 and 1625, about one-fifth of Delft's population perished. In 1635 and 1636, the dreaded disease claimed the lives of 2,000 inhabitants. In the 1650s and 1660s when Vermeer was active as an artist, hundreds more died of the same cause.

The Guild of Saint Luke and Apprenticeship

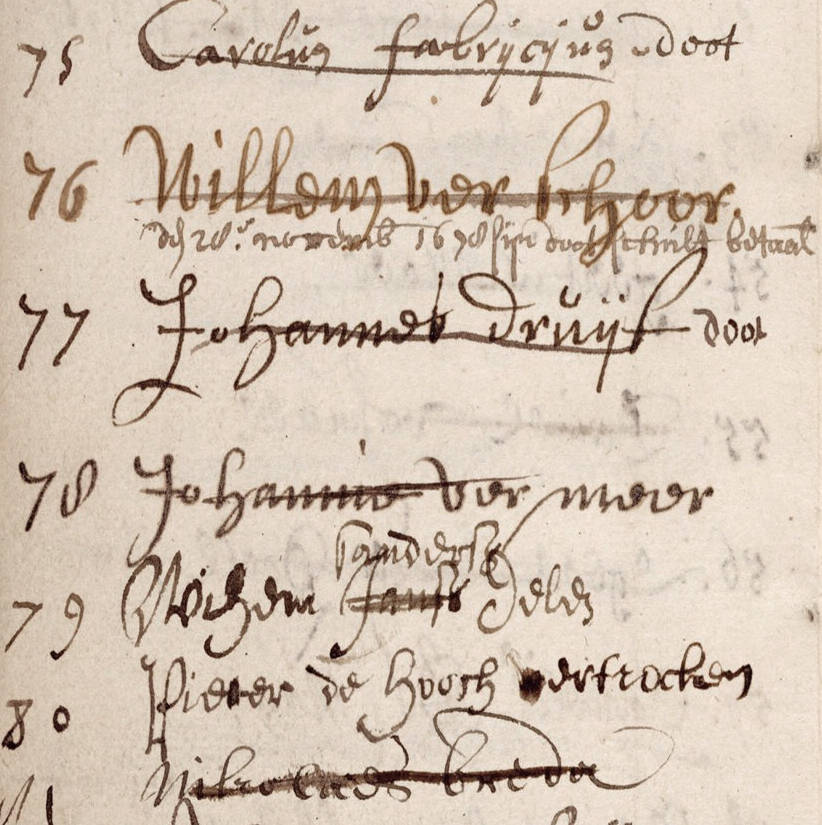

Vermeer's name at number 78 and Pieter

de Hooch's name at 80 and Carel Fabritius at 75.

Nothing is known about Vermeer's decision to become an artist. Likewise, we have no idea about what he thought about art. Not a single document links Vermeer to any other painter other than Gerrit ter Borch, with whom he witnessed a legal act in Delft just two days before Vermeer's marriage on April 20, 1653. It is not out of question that Ter Borch had journeyed to the event from The Hague, where he often resided during that period. There is a possibility that the two artists were acquainted prior to this, and it cannot be discounted that the older painter may have also been present at Vermeer's wedding.

It was once held that Vermeer traveled to Italy like a number of Dutch painters who sought inspiration from the divine works of the Italian masters. However, research later revealed that it was not Vermeer, but his namesake "Johannes van der Meer" of Utrecht who had traveled to Italy in the early 1650s.

As with most Dutch painters, Vermeer was required to undergo a fixed period of training with a master painter who belonged to the Guild of Saint Luke, the powerful trade organization which regulated the commerce of painters and artisans. During his tenure, the apprentice, who was typically an adolescent, was thoroughly instructed in the art and craft of painting and upon being admitted to the Guild, was permitted to sign and sell his own paintings as well as those of other painters. Once a member, he could take on apprentices of his own, a potential source of income in the highly competitive Dutch art market.

In December 1653, Vermeer was admitted to the Guild, presumably after having presented a so-called "masterwork" to prove his skills, and was expected to pay an entrance fee of six guilders. Normally, new admittees whose father had been members—as was the case with Vermeer—were required to pay only three guilders, provided that they had trained for two years with a recognized master of the Guild. The most plausible explanation for the higher admission fee is that Vermeer had trained outside of Delft.

The Guild was located on Voldersgracht 21, face-to-face with Mechelen and a few doors away from the Flying Fox. The Guild's principal goal was to enforce quality standards and inhibit the influx of low-quality works from other cities, undercutting the earnings of local artists. The Guild headquarters was remodeled and inaugurated in 1667. It continued to function for well over a hundred years until the Napoleonic era when new laws were introduced, forcing all guilds to close. The building itself was demolished in the 1880s.

In any case, the Guild account ledger (fig. 5) reveals that upon his entrance on December 29, 1653, Vermeer paid only 1 guilder, 10 stuivers. The balance of 4 guilders, 90 stuivers was paid three years later, on July 24, 1665. Art historians generally hold that the artist took time to pay in full due to his modest economic circumstances. Vermeer's name appears on the Guild ledger alongside other painters, such as Carel Fabritius ( 1622–1654) and Pieter de Hooch (1629–1684).

Who was Vermeer's Master?

Several names have been brought forth as Vermeer's master, including Pieter van Groenewegen (1590/1600–1658), Willem van Aelst (1627–c. 1683), Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651) (fig. 6), Carel Fabritius (1622–1654), and Jacob van Loo (1614–1670).

It is known that Vermeer's father dealt in paintings by Groenewegen and that Vermeer likely used one of his landscapes as a model for the gilt-framed picture and the open lid of the virginal in his late A Lady Standing at the Virginal, but no other evidecne ties the Delft landscape painter to Vermeer. The Delft-born Van Aelst had dealings with Vermeer's father, but once again, there is no stylistic or thematic connection between this artist's intricate still lifes and the expansive style of Vermeer's early history paintings.

Abraham Bloemaert

c. 1630

Oil on canvas, 50.2 x 64.6 cm.

Manchester City Galleries

Since there are no records of Vermeer's apprenticeship in Delft, Montias suggested that the young artist might have trained in Utrecht or Amsterdam, where his father had trained. Montias cautiously advanced the name of the elderly Bloemaert of Utrecht who was known to have taken on numerous apprentices. Furthermore, the elderly painter was also an in-law of Maria Thins' cousin Jan Geensz Thins. Bloemaert, who, however, died three years before Vermeer became a master himself is thus an unlikely candidate.

On the basis of stylistic affinities, Fabritius, one of Rembrandt's most gifted and celebrated pupils, was once one of the prime candidates for Vermeer's master because a contemporary poem by the Delft printer Arnold Bon (before 1634–1691)Arnold Bon was a Delft publisher, printer, and minor poet who served as the official printer for the city government from 1660 to about 1690. He lived on the Markt in Delft in a house known as Vinder van de Druckkonst ("Inventor of the Art of Printing"). Bon is noted for publishing Dirck van Bleyswijck’s Beschryvinge der stadt Delf (1667–1680), which included a poem praising Johannes Vermeer and Carel Fabritius. In 1652, he published a collection of his own works, featuring Dutch poems and popular songs known as Mopsjes, which were cheerful but often playful and risqué. Despite claiming they promoted aversion to lustful practices, the songs had a lighthearted and mischievous tone. describes Vermeer as "following in the footsteps" or "emulating" Fabritius. However, both terms are vague enough to discourage reading in a master/apprentice relationship. Moreover, Fabritius seems to have joined the Delft Guild of Saint Luke more than a year before Vermeer, although he may have been working in Delft before he enrolled in the Guild. Importantly, there is little trace of Fabritius' style in Vermeer paintings until a few years after Fabritius had died in the infamous Donderslag while he was painting a portrait.

Bramer, the most esteemed painter of Delft, had been traditionally considered Vermeer's teacher, a notion conforted by the fact that he was a friend of the Vermeer family and had even testified in favor of the young painter on the occasion of his marriage to the Catholic Catharina. However, between Bramer's idiosyncratic Italianate style and Vermeer's work, constitutes convincing evidence that Vermeer trained with someone else

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1657–1659

Oil on canvas, 83 x 64.5 cm.

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

While one of Vermeer's earliest known works, Diana and her Companions, can securely be related to two works of the same theme by the accomplished Van Loo, there is no evidence that Vermeer had been in those years in Amsterdam, where Van Loo lived.

In any case, it should be noted that not all painters in those times showed the influence of their masters. As Walter Liedtke pointed out, the discovery of Vermeer's master would probably not be very helpful in clarifying the artist's development—his talents may have simply been nurtured "by beginning not as a painter's apprentice but as an art dealer's son."Walter Liedtke, Vermeer: The Complete Paintings (New Haven and London: Harry N. Abrams, 2008), 20.

It seems safe to say that whoever instructed Vermeer had far less impact on the artist's professional course than his upward marriage to a young girl (fig. 7) who lived on the other side of the Delft Market Square, a stone's throw away from Mechelen, and who, very likely, posed for Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window and various other masterpieces by the artist.

Marriage

Vermeer married Catharina, who was one and a half years older than he was, in April 1653. Shortly after, both of their signatures appear on a document together (fig. 8). A cursory examination of the couple's calligraphy reveals an evident difference in personality, if one is willing to admit the influence of character upon handwriting. While Vermeer's signature is relatively undemonstrative and controlled, the sensual swirls of the "B" in "Bolnes" and plunging loop of the "h" in "Catharina" denote an uninhibited hand which belongs, perhaps, to a young girl unafraid to show her emotions. It is by and large assumed that their marriage, blessed with eleven children, was a happy one, at least until the financial collapse of the Vermeer family in the final years of the artist's life.

Catharina came from a well-to-do family in Gouda (fig. 9). Her mother, Maria Thins (c. 1593–1680), was from a distinguished, landed, old, and stronghold Catholic family from Gouda. Catharina's father was Reynier Bolnes (1591–1674), a prosperous brickmaker from Gouda as well. Three of their children survived infancy; a boy, Willem, and two girls, Maria, and Cornelia. Catharina was born in 1631 when her mother was 38. Catharina was raised Catholic. Vermeer instead, had been raised as a Protestant. Although living in close proximity—they resided no more than a two or three mintue walk from each other— the worlds the couple inhabited were far removed.

Today a number of scholars maintain that upon marriage Vermeer converted to Catholicism or, at least, he took an active part in bringing up his children in his wife's religion. Mixed marriages were not out of the question. Conversions happened. The renowned seventeenth-century poet Joost van den Vondel (1587–1679) converted to Catholicism. The writer Maria Tesselschade (1594–1649), daughter of Roemers Visscher and a friend of Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), became a Catholic in 1642, causing the good Protestant Huygens much grief. But we have no documentarey proof of Vermeer's conversion, which, however, was not unusual, given the hostility which the Catholics were subjected to.In the 17th-century Netherlands, conversion to Catholicism occurred within a complex social, political, and religious context marked by the dominance of Protestantism following the Reformation. The Dutch Republic, predominantly Calvinist, tolerated Catholicism to a degree but placed restrictions on public worship and the political influence of Catholics. Conversion to Catholicism was often a private matter, influenced by personal conviction, family ties, or interactions with Catholic clergy operating discreetly. Some converts were drawn by the rich traditions of Catholic liturgy and its emphasis on sacraments, while others sought alignment with Catholic communities for social or economic reasons, particularly in regions like Brabant and Limburg, where Catholicism remained culturally significant. Despite these conversions, Catholics often faced social marginalization, leading to the development of clandestine churches and hidden religious practices that preserved their faith during this period of Protestant hegemony. However, it has been observed that a devotional painting such as Saint Praxedis fits well with Vermeer’s presumed conversion to Catholicism shortly before his marriage in 1653 and with his links to the Delft Jesuits, which have recently come to light.Gregor J.M. Weber, Johannes Vermeer: Faith, Light and Reflection (Rotterdam: nai010 Publishers, 2023). In any case, Vermeer's presumed conversion to Roman Catholicism likely happened between the couple's betrothal and their wedding in the village of Schipluy, near Delft. Contrary to the beliefs of some early art historians who viewed Vermeer's conversion as superficial or opportunistic, Montias' research indicates that at least to those sympathetic to Vermeer's conversion to Catholicism, he was deeply entrenched in the Catholic milieu of his in-laws, suggesting a bond that went beyond mere family connections. On the other hand, the art historian Paul Abels has expressed skepticism regarding Vermeer's conversion.Paul Abels, "Church and Religion in the Times of Vermeer," in Dutch Society in the Age of Vermeer (Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, 1996). Abels reasons that Maria de Knuijt (died 1681), the wife of Pieter van Ruijven (1624–1674), who are both believed to have been Vermeer's patrons, laid out in her will that Vermeer would inherit 500 guilders from her estate, unless he predeceased her. Abels interprets this provision as a measure to keep the inheritance away from Vermeer's wife, and ultimately, the disfavored Jesuits. Abels theorizes that de Knuijt, who was a staunch supporter of the Reformed faith, did not perceive this as a risk if Vermeer was the direct recipient, possibly suggesting that Vermeer's commitment to Catholicism was weaker than that of his wife. Factors pointing toward a possible conversion include Maria Thins' hesitancy about his marriage to Catharina, certain Catholic names given to his children, and speculation about his eldest son's religious vocation. Yet, these indicators only suggest a sympathy towards Catholicism, not definitive proof of conversion.

In all, Catharina and Vermeer had 15 children: Maria, Elisabeth, Cornelia, Aleydis Beatrix, Elizabeth Catherina, Johannes, Gertruy, Franciscus, Catherina, Ignatius, and an unnamed child born between July and September 1674. Three other children were buried in 1667, 1669 and 1673. One other child born in 1672 died in or after 1713. The child born in 1674 and died in 1678. At the artist's death, eleven children were recorded as being alive.

Maria must have closely considered her daughter's marriage with Vermeer, since her own marriage had been miserable.Walter Liedtke, Michiel C. Plomp, and Axel Rüger, Vermeer and the Delft School (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 147. "Catharina's childhood memories were full of violence, fits of temper and tears. Her father, after 13 years of marriage, had become an ogre. Maria's relatives and neighbors were to testify that they saw him insulting his wife, kicking her, pulling her naked from her bed by her hair when she was sick, attacking her with a stick when she was pregnant, and chasing her out of the house. She was forced to eat her meals by herself. On one occasion, Catharina, aged nine, ran to her neighbors in fright, yelling that her father was about to kill her sister Cornelia. Maria received the support of her sister and brother, who was himself stabbed in a fight with one of Reynier's brothers while Reynier was bolstered by his son Willem."Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2001), 37-38.

Years later, after the unhappy couple had been legally separated, Catharina and her mother moved into the quiet Catholic enclave called the Papenhoek, (Papists Corner), in Delft, perhaps, seeking solace from their traumatic life in Gouda. Willem, Catharina's brother, who had sided with his father, later moved in with them when Vermeer was living—and probably painting—there as well.

from Cesare Ripa's iconographical guide which Vermeer himself used to compose his Art of Painting and Allegory of Faith

"Vermeer's marriage, which was outside the family's religion and social class, was exceptional. It entailed a move from the lower, artisan class of his Reformed parents to the higher social stratum of the Catholic in-laws, and from Delft's Markt to the Papenhoek. Wayne Franits, Vermeer (Art & Ideas) (London: Phaidon Press, 2015) 161. However, there is considerable disagreement among scholars concerning Vermeer's zeal for his adopted faith. Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. has argued that Vermeer's artistic development had been deeply influenced by his conversion citing as proof the three religious pictures painted by Vermeer; Saint Praxedis (Wheelock is virtually alone in supporting its authenticity), Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, and the late Allegory of Faith.

In any case, "on the evening of April 4, 1653, Vermeer's older colleague Bramer and an army captain named Bartolomeus Melling, who had served in Brazil and was now a standard-bearer in the forces of the States-General, called on Maria Thins. They had with them a Delft lawyer named Johannes Ranck. It seems to have been an ecumenical delegation on the young couple's behalf, with Bramer apparently representing the Catholic interest and Melling the Protestant, come to talk Catharina's mother around. Maria's sister Cornelia was also on hand, giving support and sympathy. The visitors asked Maria Thins whether she would sign a document permitting the marriage vows or banns to be published and registered. Maria replied that she would not sign such an act of consent. Despite this—a subtle distinction—she would put up with the vows being published; she said several times that she wouldn't stand in the way of this...In other words, she didn't welcome the marriage, but wouldn't block it."

When it came to the crunch, it seemed that Maria Thins wasn't happy about her daughter marrying Johannes Vermeer, son of Mechelen. Neither Johannes nor Catharina had presumably told Maria that Johannes had in the family a counterfeiter as maternal grandfather and a bankrupt bedding dealer for paternal grandmother—though Delft being a small enough place in terms of gossip, she may have heard of these relations of his."Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2001), 61-62

When Vermeer's betrothal was registered, he was listed as residing at "opt Marctveld," which was the marketplace's name in the seventeenth century. Catharina's location is noted as "mede aldae" (also there), and there are differing opinions in art-historical literature regarding whether she lived with Johannes in the Mechelen house before their marriage. For example, Kees Kaldenback has advanced that she had eloped. Most likely, however, they did not cohabit before marriage, as this was generally frowned upon in the seventeenth century. Maria Thins's opposition to the marriage was minimal, likley influenced more by her moral values and community than her son-in-law.

Following his marriage, Vermeer seemed to have distanced himself from his own family, a fact which can be seen in his apparent failure to name any of his children after his mother or father, a common practice at the time both in Protestant and Catholic families. The couple named their first daughter Maria, in honor of Maria Thins, and their first son Ignatius, after the patron saint of the Jesuit Order. For more information on Vermeer's Catholic marriage and the implications it had on Vermeer's life and work, click here. Except for his ties with the painters of Delft's Guild, evidence suggests that Vermeer's social relationships did not extend far from the Papenhoek, an inevitable consequence of a Catholic marriage and probable conversion to Catholicism. Although Catholics comprised about 20% of Delft's population and were by and large tolerated, conversion to Catholicism was not taken lightly in some quarters of the town.

Early Works

In the time when Vermeer was beginning his journey as a master painter, Delft emerged as a premier arts hub in the Dutch Republic, thanks to the influx of innovative artists. By around 1650, talents like Gerard Houckgeest, Carel Fabritius, and Pieter de Hooch had made Delft a focal point for artistic brilliance, particularly in genres like architecture painting, cityscapes, and genre painting. Their pioneering approaches to perspective and color crafted unparalleled illusions of space and light, drawing inspiration from Delft's urban landscapes. This wave of innovation also had an impact on local artists, including Vermeer, Daniël Vosmaer, and Hendrick van Vliet.

At the outset of his career, Vermeer surveyed the styles of various seventeenth-century artists, not only those whose works he might have seen in Delft. The first two surviving works reveal the ambitious young painter grappling with the problems of what art theorists considered the noblest form of painting: istoria, or history painting. History painting was intended to offer uplifting or cautionary narratives to encourage contemplation of the meaning of life. The most suitable scenes to be represented were drawn from classical literature, ancient mythology and the Bible.

In his early career, Vermeer created four distinct paintings that differ significantly from his later, renowned pieces. These early works, which include biblical, mythological, and historical subjects, showcase his aspirations to be recognized as a history painter – a prestigious role that demanded both artistic skill and knowledge of the narratives being depicted. Although these paintings, two of which are dated 1655 and 1656, bear by Vermeer's signature, their attribution sparked debate upon discovery due to their stark difference from his mature style. They highlight Vermeer's initial ambitions and his brief journey as a young history painter. Christian Tico Seife, "Early Ambitions: Vermeer’s Journey from Bible to Brothel," in VERMEER, ed. Pieter Roelofs & Gregor Weber, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023, 126.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1653–1656

Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 105 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

Although Vermeer's two surviving history paintings are quite large and broadly painted, they betray serious problems in composition, perspective, anatomy, and handling of light. Some Vermeer scholars believe that the first of the two works, Diana and her Companions (fig. 10), was a bid to gain entrance to the moneyed Hague court where the classical Diana theme was much in vogue. If that was the case, it is not too difficult to understand why the artist's appeal was left unanswered. Although extraordinarily interesting from an art-historical point of view, the juvenile work was, at least by contemporary standards, hardly a masterpiece. The heads of the foreground figures are positioned such that their faces are cast in a deep shadow making it impossible to divine their emotions or characters. The poses—four out five of the figures bend their heads downwards in a frieze-like procession—reiterate the melancholy mood of this picture for which the artist provides no psychological escape except for an unfriendly dark sky. The haphazard distribution of lights and darks runs counter to the period recommendation to group lights and darks together in order to avoid producing a "checkerboard" effect. The brass basin seems to slip off the bottom of the painting and the large rock in the foreground, in one art historian's opinion, looks like "a sack of potatoes." The back of the left-hand background figure is executed so approximately that had the viewer not been familiar with the painting's narrative, it could be taken either as a male or female.

However, the young painter made rapid progress. The second history painting, the Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, is artfully composed and fluently painted. The foreshortening of the seated figure's head and clutched hand demonstrate a technical confidence not seen in the earlier Diana, rivaling—in its exceptional economy of tone—the works of Utrecht painter Hendrick ter Brugghen, whose religious pieces may have inspired this Vermeer work. The colors are lush, the atmosphere resonates with light and shadow and brushwork is reassured, although somewhat complacent in the definition of Christ's robe. However, the artist owed as much to window shopping as to his own compositional prowess. The figure of the Christ and the kneeling Mary can be traced to a painting of the same subject by Erasmus Quellinus II while the poses and positions of all three figures share much in common with an engraving by Georg van de Velde after Otto van Veen. Borrowing of this sort—termed aemulatio—was not looked down upon per se but, on the contrary, considered a fundamental part of the learning process. What was important was to make the borrowing one's own.

Other than the Diana and her Companions and Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, period source inform us that Vermeer painted at least two more history paintings: "En graft besoeck - ende van der Meer 200 guilden," a Visitors to a Tomb, probably a representation of the Three Marys at the Sepulcher, a story from the New Testament, and a mythological Jupiter Venus and Mercury, perhaps a misunderstanding of Jupiter, Mercury, and Psyche (or Virtue), the more common motif of the two. On June 27, 1657, the former work was in the collection of Johannes Renialme, a young "gentleman dealer" who came from a distinguished family with members in Antwerp and Venice. AWhile the young painter must have been justifiably pleased to have his work in a reputable art collection, it was valued at 20 guilders, in contrast to a "perspectieff" by Hendrick van Vliet—whose most salient feature is its perspective—valued at 190 guilders.. Although Vermeer would soon veer to an entirely new genre for which he is known, the late Allegory of Faith shows that he had not completely abandoned religious subject matter.

Johannes Vermeer

1656

Oil on canvas, 143 x 130 cm.

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

The young artist's next step was another large-scale work, The Procuress (fig. 11), a bordeeltje, or bordello scene, in the manner of the Utrecht Caravaggists. Why Vermeer turned so suddenly from high-brow to low-brow subject matter is not known. Perhaps he was piqued by his mother-in-law's personal art collection which contained the striking Procuress by Dirck van Baburen or by other works of competent painters of the Utrecht School. Vermeer would later incorporate Baburen's work in the background of two of his own compositions. On the other hand, the young Vermeer may have simply wished to try his hand as something more stimulating than brooding saints and meditative goddesses. Although the artist's treatment of the bordello motif is indeed unconventional—instead of flaunting bare breasts, a racy silk dress and a plumed hat which were key selling points of the bordello genre Vermeer's young prostitute wears tasteful lace and a simple yellow garment closed up to the neck—the bordello genre had already reached full maturity and was no longer "cutting edge" subject matter.

To those familiar only with Vermeer's chaste interiors, the subject matter of The Procuress may surprise. It should be kept in mind, however, that Vermeer was born and raised in an inn. Dutch inns were synonymous with various collateral activities ranging from relaxed conversation, to financial transactions, art dealing and undisguised sex peddling. If Vermeer's father's inn was not a disreputable place, as evidence seems to indicate, the boy artist would have not been blind to what was a daily occurrence in urban life. In a country where prostitution, procuring, and adultery were criminal offenses, where the word hoererij (whoredom) denoted any kind of non-marital sexual intercourse, and where religious piety was deeply felt not only by Calvinists but by people of other denominations, a market still existed for pictures of half-nude, lascivious women whose charms were obviously for sale.Lotte C. van de Pol,"The Whore, the Bawd, and the Artist: The Reality and Imagery of Seventeenth-Century Dutch Prostitution," Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 2, no. 1–2 (2010), Suffice it to say that even the artist's fervent Catholic mother-in-law owned a few pictures that probably would not be hung on any wall of many an American household.