The lives of seventeenth-century Dutch painters, including Vermeer's, were deeply affected by the Guild of Saint Luke. This professional trade organization for artists and artisans regulated the commerce and production of various professionals, including potters, engravers, glass makers, tapestry weavers, faiencers, booksellers, sculptors, painters, and even art lovers (the so-called liefhebbers). We also find with the guild architects, tapestry weavers, embroiderers, glass makers, glass painters, glass sellers, engineers, surveyors, mapmakers, map coloring specialists, calligraphers, typeface makers, printers, book binders, and as the proverbial odd ones out, chair painters, and a furniture joiner. In Delft, the goldsmiths were grouped in a separate guild. Each city had its own self-governing guild which protected, promoted, and defended the interests of its members. In general, Guilds also made judgments on disputes between artists and other artists or their clients. In such ways, it controlled the economic career of an artist working in a specific city, while in different cities they were wholly independent and often competitive against each other.

The Guild was named after its patron saint, the evangelist Luke, who, according to legend, had painted a portrait of the Virgin Mary. Further, Luke’s gospel is known as the most visual account in the Bible, including details and atmosphere.

Membership in the guild brought along benefits, obligations, and rules. Guild rules varied greatly. In common with the Guilds for other trades, there would be an initial apprenticeship of at least three, more often five years. Typically, the apprentice would then qualify as a "journeyman," free to work for any Guild member. Some artists began to sign and date paintings a year or two before they reached the next stage, which often involved a payment to the Guild, and was to become a "free Master". After this the artist could sell his own works, set up his own workshop with apprentices of his own, and also sell the work of other artists. Anthony van Dyck achieved this at eighteen, but in the twenties would be more typical. A Guild member was, for instance, not allowed to take over another member's job except in cases of force majeure such as illness or drunkenness. A simple sick benefit system existed, providing income and medical aid in case a member got seriously ill. Members were expected to attend at funerals of other members. Fees and fines for trespassing these rules were collected by a footman.

When Vermeer became a Guild member, the Guild did not have a dedicated venue for its members to convene. Instead, meetings were likely hosted in the residences of painters or at inns. It is plausible that some of these gatherings occasionally took place at Mechelen, an establishment operated by Vermeer's father, Reynier, who was also a guild member.

The Guild of Saint Luke in Delft was officially founded on May 29, 1611, although it had existed for some time before that date. It was housed in the former chapel building of the Oude Mannenhuis almshouses on Voldersgracht, which underwent significant renovations. From the guild's location, Vermeer could gaze upon the back of Mechelen, the place where he spent his childhood, which must have evoked profound emotions in him.David de Haan, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Babs van Eijk, and Ingrid van der Vlis, Vermeer's Delft (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, Museum Prinsenhof Delft, 2023), 31.

The board of the Guild of Saint Luke consisted of six members: two potters, two stained-glass artists, and two painters. They were led by a dean who was also a member of the forty-member municipal advisory council.. The painters were the most influential group within the guild. "To join the guild, an aspiring worker had to serve a long apprenticeship, generally of six years though it could be shorter if he produced a work—a masterpiece—proving his skills. The would-be artist-member had to be a resident of Delft and pay an incomstgelt, 'entrance fee': twelve guilders for those born outside Delft, six guilders for natives, and three guilders for the son of a master who was already a member of the Delft guild."Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2002), 41.The annual dues were six stuivers. The guild in Delft had six headmen who oversaw various responsibilities, including ensuring rules were followed. A portion of the guild's earnings went to supporting impoverished members. Non-members and outsiders faced fines if they sold art in Delft, and only masters could sign their works.

It is uncertain if the Delft guild had female members, although there were examples of female artists in guilds in other cities. Female artists, if fact, faced numerous challenges in the seventeenth-century Netherlands. They often were porhibited from attending art academies, making guild memberships crucial for their training. However, even within guilds, women typically could not hold higher positions or participate in decision-making. They were also often restricted to certain genres, like still lifes or portraits, and were discouraged from painting historical or religious scenes, which were considered more prestigious.Judith Leyster, a notable artist of the Dutch Golden Age and member of the Haarlem Guild of Saint Luke, specialized in genre scenes and portraits, but her works were often wrongly attributed to male contemporaries. Maria van Oosterwijck, unaffiliated with any guild, was celebrated for her detailed flower paintings and had royal patronage. Rachel Ruysch, influenced by her botanist father, was renowned for her flower still lifes and enjoyed a prolific career despite not being in a guild.

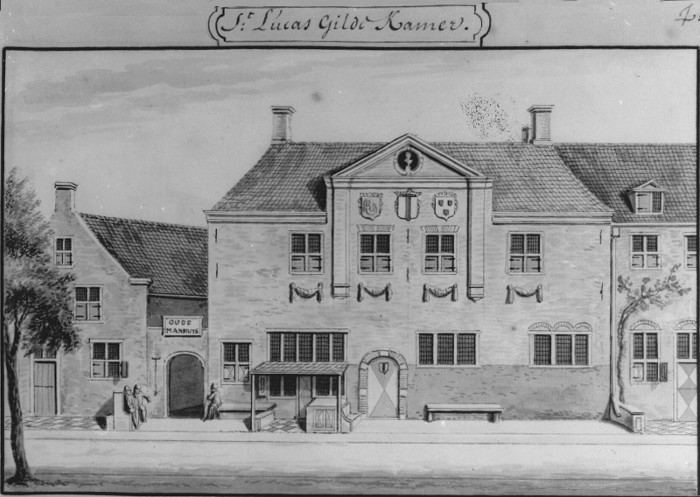

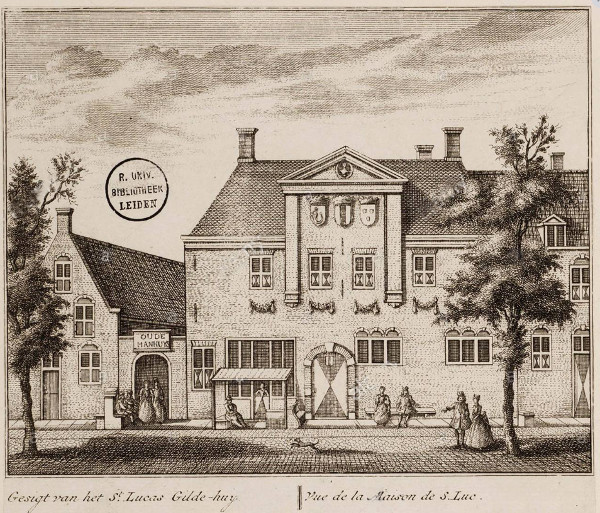

In the Beschryving der Stadt Delft (Description of the City of Delft) published in 1667, Dirck van Bleyswijck gave a description of the new guild hall which included various features that are clearly recognizable in a drawing (fig. 3) made by Abraham Rademaker and copied in an engraving (fig. 4) by Leonard Schenk. There are four windows on the first floor (with stained glass made specially by the glassmakers in the Guild. Below each of the four windows was a festoon carved in white stone (fig. 1) representing the emblems of the Guild's four main trades: painters, glassmakers, potters, and booksellers. A niche with shields and a bust of the fabled Greek painter Apelles is centered inside the structure's classical pediment with According to van Bleyswijck, there was a 'very large and airy room" with a fireplace. The interior decorations included a ceiling painted by Leonaert Bramer and a canvas mural by Cornelis de Man depicting a triumphal arch. A drawing made by Gerrit Lamberts (fig. 2) in c. 1820 represents a part of the guild's facade.

Gerrit Lamberts

c. 1820

Graphite, pen and brown ink, brush and gray ink, 24.9 x 19.3 cm.

Gemeenarchief, Delft

The drawing reveals a glimpse of the upper part of the Delft Guildhall's central arched doorway above the arched bridge as seen through the Oude Manhuissteeg (Old Men's Alley).Opposite this alley and bridge, the Oude Mannenhuis (Old Men's House) was located on the Voldersgracht from 1411. This institution consisted of a number of rooms or houses around a courtyard and a chapel. From the middle of the 17th century, it was used as the Sint-Lucasgildehuis (Guild of Saint Luke House). The entire complex was demolished in 1876 for the construction of a primary school, and it was reconstructed in 2007. The facade on the left represents the inn/house owned by Vermeer's father.

Click here for maximum resolution image drawn from the Delft Archives website.

Purpose

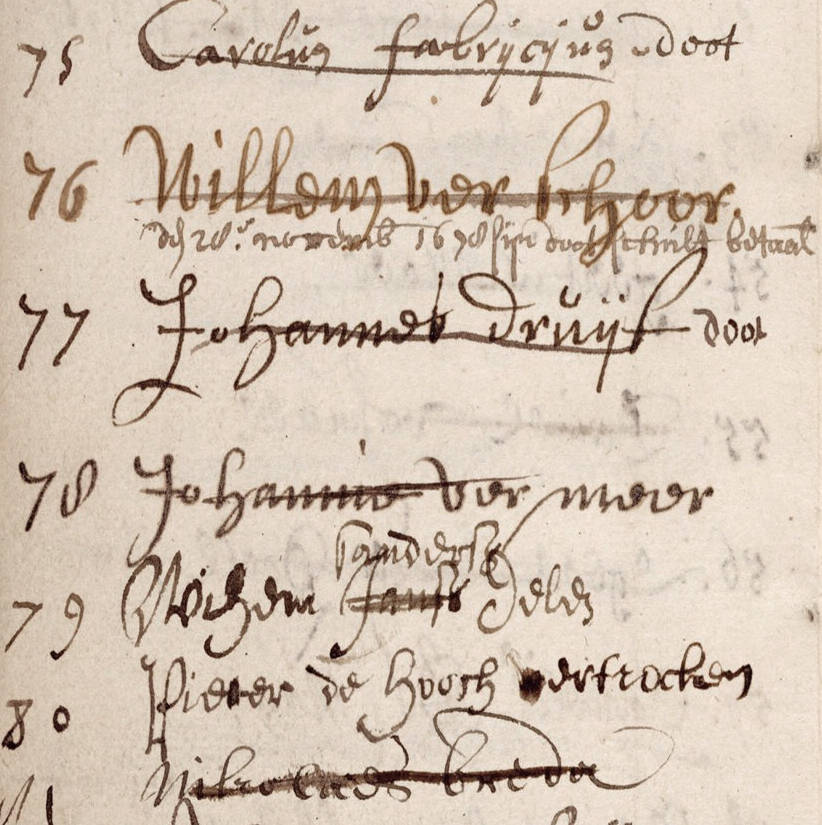

The Guild of Saint Luke must have been founded in the Middle AgesGuilds, especially prominent ones like the Guild of Saint Luke, were central to medieval and early modern European societies, overseeing crafts and trades. Joining required fees, apprenticeships, and the creation of a masterwork to prove one's skill. Within the guild, strict trade and quality standards prevailed, sometimes inhibiting innovation. However, the benefits were significant. Guilds offered exclusivity in trade regions, skill development, and were close-knit support systems during tough times. They were also networking hubs, dispute mediators, political influencers, and centers for social and religious events. In short, guilds expected adherence to rules but offered members security, knowledge, and camaraderie. but it was first mentioned in documents in 1545. "In Delft, as in many other artistic centers, artists and artisans primarily collaborated to restrict the import of artworks from outside the city. This was generally accomplished by allowing only members of the local Guild of Saint Luke to sell paintings. Auctions of paintings brought in from elsewhere were forbidden except at the annual fairs (in Delft, the main public room of the town hall was used for this purpose)." 3In exchange, member artists were required to pay an entrance fee of 6 guilders.Vermeer, registered as "Johannis Vermeer," became a master painter in the Delft Guild of St Luke in 1653 at the age of twenty-one. He was inscribed as member no. 78 in the master-book of The Guild and paid only one and a half guilders of his six guilders entry fee, perhaps planning to pay the rest when he had begun to make painting pay. His father, a guild member, might have facilitated in this arrangement.

Regarding Vermeer's registration with the Guild, there was an interesting discrepancy. He was charged an entrance fee of six guilders, which was double the expected rate for someone like him, being the son of a Guild member. A concessionary fee of three guilders might have been expected, particularly if he had apprenticed under a Delft guild painter for several years. This deviation in the expected fee might have been because his father, Reynier, although a long-standing Guild member, was not a professional painter but rather a dealer in art and "caffa" worker. Reynier's recent death might have also played a role. Another theory posits that the full fee was due to the perception that Johannes had pursued his studies outside of Delft.

A significant issue for the Delft Guild of St Luke, and for Vermeer as a member, was the absence of a daily saleroom in Delft to market paintingss. Lacking this outlet, some Delft painters opened up their private fore-houses so that prospective buyers could look at the stock. Only during one week each year were Delft residents permitted to trade art at the major annual fair and market. During that time the sale of paintings was allowed for all, without restrictions.

Abraham Rademaker

c.1700

Drawing

c. 1732

Leonard Schrenk

Engraving after a drawing by Abraham Rademaker made in 1700

Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden, Leiden

Rademaker's etching differs in a number of details from Schrenk's original drawing.

Apprenticeship

All aspiring painter members of the Saint Luke guild had to complete an apprenticeship, typically lasting four to six years. In the 1604 guide Het Schilderboek by Karel van Mander, the intricacies and structure of an artist's apprenticeship were laid out. Pupils were taught the arts of composition, sketching, shading, and precision drawing using an array of tools like charcoal, chalk, and pen. Emphasis was placed on neatness, with instructions highlighting the importance of working meticulously with stumps or pastels.

The period spent in a recognized master-painter's workshop ensured the young artist a thorough familiarization with the complexities of his craft. It should be remembered that in Vermeer's time much of the artist's materials had to be produced by the painter, and painting techniques were far more elaborate than those of most contemporary artists. For example, since paint was not sold in commercial tubes as it is now, each morning the artist had to hand-grind the colors he intended for use in the day's work. Hand-grinding paint presents a number of difficulties and requires much practice. This rather laborious task was often left to the apprentice. Furthermore, a great deal of significance was given to cleanliness. Pupils were instructed to maintain clean tools and ensure their paintings were safeguarded from dust.

The young pupil was first instructed in drawing plaster casts of Classical sculpture. Many of these casts can be seen in depictions of artists' studios; one, of a face, perhaps the god of light, Apollo, can be seen on the table in Vermeer's Art of Painting. Next, the apprentice came to grips with the subtleties of representing the live model, and only afterward did he pick up brush and paint. He sometimes was allowed to work on the less-important sections of the master's own paintings, such as large areas of unmodulated color or monotonous background foliage. The master closely followed his pupil's progress and corrected him when needed. Some talented artists were able to leave their master' s studio within a few years. Rembrandt progressed so rapidly that he already had pupils of his own at the age of 21. As the apprentice's skills improved he worked on the more complex areas such as drapery and hands. Guild candidates were given a proper test assignment and with their apprentice tools, they had to produce their masterpiece of professional craft within a given period of time. Those who failed the test had to wait and try and train again for a period of 58 weeks.

The financial aspect of these apprenticeships was also notable. Training was expensive. However, if an apprentice decided to pursue their learning away from their hometown in the final years, this cost would see a substantial increase.

On average, a young apprentice's family who lived with his parents paid between 20 and 50 guilders per year. With board and lodging included, up to 100 guilders were required to study with the more famous artists such as Rembrandt or Gerrit Dou. If we consider that school education generally cost two to six guilders a year and that apprenticeship generally lasted between four and six years, the financial burden of educating a young artist was considerable. Moreover, during the apprenticeship, the parents had to do without their son's potential earnings because during this period the apprentice could not sign and sell his own paintings. Instead, all the works the apprentice produced became property of his master. These could even be sold under the master's signature. Evidently, the allure of significant future earnings must have been significant.

In the master's studio, the apprentice was exposed to the thoughts, opinions, and artistic theories which circulated rapidly among artists' studios. A number of Dutch painters had traveled to Italy to study the works of the Italian Masters and returned with knowledge of new techniques and styles which were rapidly diffused. Painters' studios were often lively places frequented patrons and men of culture. Animated theoretical debates and exchange of practical information concerning the art market must have been the norm.

Vermeer's name at number 78 and Pieter

de Hooch's name at 80 and Carel Fabritius at 75.

Although Vermeer must have undergone an apprenticeship like every other painter in Delft, there remains no evidence of where or with whom he had studied. Nevertheless, his path to the Saint Luke Guild was smoother since his father, Reynier Jansz, had already initiated the guild membership process.

For some time it was thought that Bramer, a native painter of Delft, might have been his master. This conjecture was based primarily on documentary evidence that suggests a certain familiarity between the Vermeer family and the Bramer. But Vermeer's artistry has little in common with that of Bramer's dark, Italianate style even though his initial subject matter was compatible with the Classical ideas of the elder painter.

Vermeer's biographer, John Michael Montias, concluded that from the scanty evidence available that Vermeer probably spent some time learning his craft in Utrecht, and possibly in Amsterdam as well, before returning to his home town in 1653. In Utrecht, Vermeer's mother-in-law, Maria Thins, had distant relations with a well-established painter, Abraham Bloemaert, and other inhabitants of the city. Maria Thins also possessed a number of paintings by Utrecht painters in her private art collection which were to later appear in the background of Vermeer's interior scene. This hypothesis does not, of course, exclude the possibility that he may, when he was thirteen or fourteen, have had an initial apprenticeship of two to three years in Delft with Bramer, Evert van Aelst, or some other acquaintance of his father's. In any case, no documents have come to light that testify to Vermeer's presence either in Utrecht or Delft in the period in which he would have been an apprentice.

However, as Walter Liedtke suggested, certain documents hint that Vermeer might not have completed a formal apprenticeship in Delft or elsewhere.Walter Liedtke, Michiel C. Plomp, and Axel Rüger, Vermeer and the Delft School (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 15. Although Vermeer is mentioned in four Delft records from April 1653, none label him as a painter, a title typically given to both apprentices and masters. When Vermeer joined the painters' guild in December 1653, he was charged a fee of six guilders, but he only paid one and a half guilders initially, settling the balance in July 1656. According to the guild's 1611 regulations, sons of guild members who had trained for two years under a Delft guild master should have been charged only three guilders. Some speculate that the higher fee indicate Vermeer trained in a different city. However, his financial constraints make this unlikely. It's also possible that the full fee was charged because Vermeer hadn't completed a standard apprenticeship.

We do know, however, that Vermeer was admitted to the Delft Guild on December 29th, 1653.. His name can be seen on the register of the guild (fig. 6) at number 77. The names of Pieter de Hooch (80) and Carel Fabritius (75) also appear on the same document.

On Saint Luke's Day, October 18th 1662, the artists of Delft chose Vermeer to be the vice-dean of their guild (1662 and 1670), which would seem to be proof that at that time he must have been a respected and highly-thought-of artist and citizen. However, by the time Vermeer was elected headmaster, many artists residing in Delft had moved to the more prosperous Amsterdam, so his election might not have been as significant as commonly believed.7

The Guild of Saint Luke, dissolved in 1833, gradually fell into disrepair and was ultimately demolished in 1879 (fig. 5).8 In its place was constructed the Jan Vermeer elementary school which was recently cleared to make way for a scale reconstruction of the original Guild. This building now houses the Vermeer Center.

Click here for maximum resolution image drawn from the Delft Archives website.