Discovery

Forgers, by nature, prefer anonymity and therefore are rarely remembered. An exception is Han van Meegeren (1889–1947). Van Meegeren's story stands out uniquely, and it is arguably the most dramatic art scam of the twentieth century.

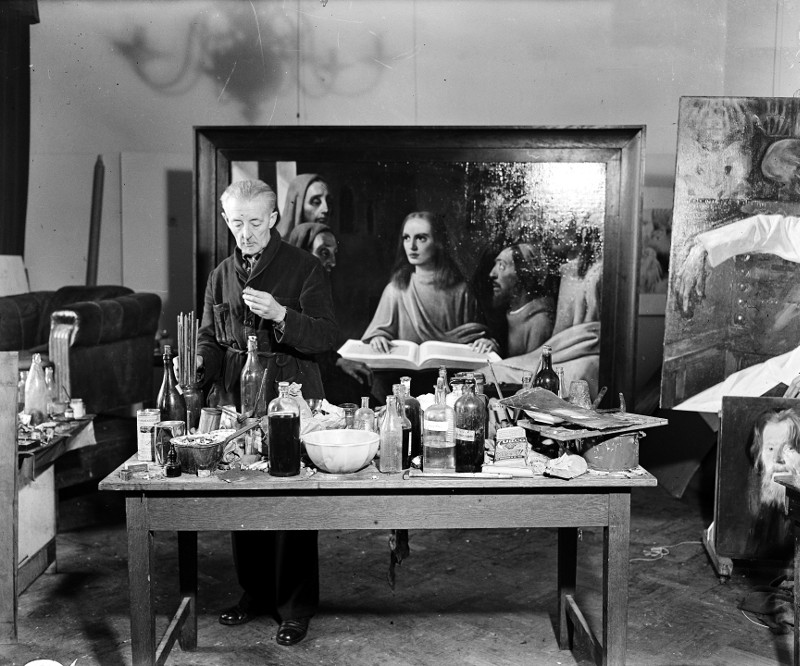

In 1937, Abraham Bredius, who as one of the most authoritative art historians had dedicated a great part of his life to the study of Vermeer, was approached by a lawyer who claimed to be the trustee of a Dutch family estate in order to have him look at a rather large painting of a Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus (fig. 1). Shortly after having viewed the painting, the 83-year-old art historian wrote an article in the Burlington Magazine, the "art bible" of the times, in which he stated, "It is a wonderful moment in the life of a lover of art when he finds himself suddenly confronted with a hitherto unknown painting by a great master, untouched, on the original canvas, and without any restoration—just as it left the painter's studio. And what a picture! Neither the beautiful signature... nor the pointillés on the bread which Christ is blessing, are necessary to convince us that we have here—I am inclined to say—the masterpiece of Johannes Vermeer of Delft. . . quite different from all his other paintings and yet every inch a Vermeer. In no other picture by the great master of Delft do we find such sentiment, such a profound understanding of the Bible story—a sentiment so nobly human expressed through the medium of highest art."

Han van Meegeren

1936–1937

Old canvas, relined, 115 x 127 cm.

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Few doubts were advanced by his colleagues since Bredius' opinion was taken as gospel in the art world, so much so that he had been nicknamed "the Pope."

This work, that today seems so heavy-handed and awkward, was in reality a fake by Han van Meegeren, a mediocre Dutch artist who had lived and worked in relative obscurity.

The Trial

In May 1945, Van Meegeren was arrested, charged with collaborating with the enemy, and imprisoned. His name had been traced to the sale made during WW II of what was then believed to be an authentic painting byVermeer to Nazi Field-Marshal Hermann Goering. Shortly after, to general disbelief, Van Meegeren came up with a very original defense against the accusation of collaboration, which was then punishable by death. He claimed that the painting, The Woman Taken in Adultery, was not a Vermeer but rather a forgery by his own hand. Moreover, since he had traded the false Vermeer for 200 original Dutch paintings seized by Goering at the beginning of the war, Van Meegeren believed he was a national hero rather than a Nazi collaborator. He also claimed to have painted five other "Vermeers" as well as two "Pieter de Hoochs" all of which had surfaced on the art market since 1937.

Han van Meegeren, after Vermeer

1942

This video on the Van Meegeren affairs by Hans Wessles (produced by the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, - English subtitles) is extraordinarily well done. It contains interviews, period news clips and even clips of Van Meegeren during his trial.

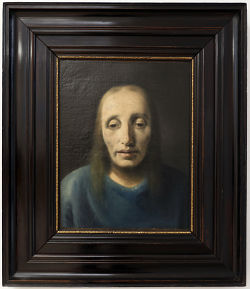

The trial of Van Meegeren (fig. 2) began on October 29, 1947 in Room 4 of the Regional Court in Amsterdam. In order to demonstrate his case, it was arranged that, under police guard before the court, he would paint another "Vermeer," Jesus Among the Doctors (fig. 3), using the materials and techniques he had employed for the other forgeries. During the incredible two-year trial, Van Meegeren confessed that "spurred by the disappointment of receiving no acknowledgments from artists and critics....I determined to prove my worth as a painter by making a perfect seventeenth-century canvas." "During the investigation, Van Meegeren revealed that having once fooled the art world with Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus, probably his best forgery, he was encouraged to try new forgeries. He painted a head of Christ, sold it through an intermediary and then "found" the Last Supper for which it was a supposed study. The buyer of the Christ painting was only too eager to snap-up the full-scale painting."Hans Kongsberg and the editors of Time-Life Books, The World of Vermeer: 1632–1657 (New York: Time-Life Books, 1967).

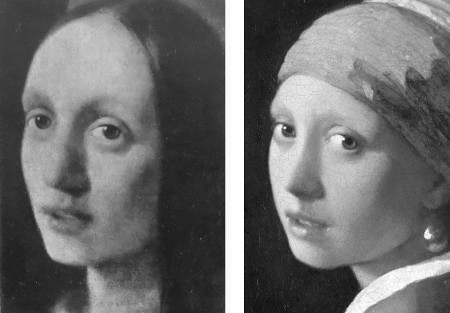

"Perhaps the greatest problem that faced Van Meegeren was the secrecy in which he had to work. He could hire no models since they might talk. For The Last Supper, he was forced to rely mainly on his imagination and it is a wonder that he dared such an accomplished composition, involving 13 figures in a variety of poses. At one point he stole directly from Vermeer, using the head of the Girl with a Pearl Earring for his head of Saint John (fig. 4)."Hans Kongsberg and the editors of Time-Life Books, The World of Vermeer: 1632–1657 (New York: Time-Life Books, 1967).

Van Meegeren spent four years working out techniques for making a new painting look old. The biggest problem was getting oil paint to harden thoroughly, a process that normally takes 50 years. He solved the dilemma by mixing his pigments with a synthetic resin, Bakelite, instead of oil, and subsequently baking the canvas. Now he was ready to begin. He took an actual seventeenth-century painting and removed most of the picture with pumice and water, being most careful not to obliterate the network of cracks, which had an important role to play."Hans Kongsberg and the editors of Time-Life Books, The World of Vermeer: 1632–1657 (New York: Time-Life Books, 1967)..

Han van Meegeren

c. 1939

Oil on old canvas, relined

48 x 30 cm.

Museum Boijmans Van

Beuningen, Rotterdam

After having tried his hand at a few typical Vermeer interior compositions, for whom the artist is renowned, Van Meegeren had what might be called his stroke of genius. Instead of forging variations of the interiors which could be compared to works hanging in museums, Van Meegeren chose to forge an early Vermeer of a religious theme based on a composition of Caravaggio. Scholars had long suspected that Vermeer had been to Italy and Van Meegeren's lost painting would have confirmed that. The subject and early technique of the painting also helped to mask his own technical and expressive inadequacies.

At the end of the trial, the collaboration charges were changed to forgery and Van Meegeren was condemned to one year in confinement, but it was said he was tickled to get only one year in jail. "Two years," he told a reporter, "is the maximum punishment for such a thing. I know because I looked it up in our laws twelve years ago, before I started all this. But sir, I'm sure about one thing: if I die in jail they will just forget all about it. My paintings will become original Vermeers once more. I produced them not for money but for art's sake."

Epilogue

The doubts regarding the international art establishment spurred by the Van Meegeren case resulted in years of a much-needed self-examination. Art historians, connoisseurs, museum directors, and unscrupulous dealers had all been involved. Above all, contemporary methods of evaluating the work of master painters required a profound reconsideration. "The dénouement of the Van Meegeren affair brought about a kind of a catharsis. The clearest example of this is found in Arie Bob de Vreis' Vermeer monograph. The first edition in 1939 sketched a picture of the artist that had been shaped by Hannema's exhibition.In 1935, Bredius' pupil Dirk Hannema (1895–1984) curated an exhibition in Rotterdam in which six of the fifteen paintings attributed to Vermeer were not authentic. Hannema was a notable Dutch art collector, museum administrator, and, to some extent, a controversial art authenticator. He served as the director of the Museum Boijmans (now known as Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen) in Rotterdam from 1921 to 1945. Under Hannema's leadership, the museum experienced significant expansion of its collection through various acquisitions. However, his directorship was not without controversy. His association with the German occupation government during World War II led to his dismissal from the museum. After the war, he faced imprisonment for a brief period due to accusations of collaborating with the Nazis. While Hannema's legacy in Dutch art institutions is marked by his contributions, especially in terms of acquisitions, his mistaken art attributions, particularly related to Vermeer, have somewhat overshadowed his reputation. Nevertheless, in understanding Hannema's life and work, it's essential to acknowledge the historical context and the challenges that come with art authentication. The second edition was published in 1948. Not only was the text completely revised, but the catalog of the works had been reduced from forty-three to the now-familiar thirty-five. De Vries explained: 'It was only after the war that this bewildering forgery business had come to light. It opened my eyes completely. I now feel that I have to remove every doubtful work from the artist's oeuvre"Ben Broos, "Malice and Misconception," in Vermeer Studies, eds. Ivan Gaskell and Michiel Jonker (National Gallery of Art Washington D.C.; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998), 27. "The post-Van Meegeren period saw the publication of monographs by Pieter T. A. Swillens, Sir Lawrence Gowing, Vitale Block, and Ludwig Goldscheider, but it was above all Albert Blankert's sober study of 1978 that acted as a kind of medicinal purge. In an addition to the critical catalogue, the book contained an important chapter on 'Vermeer and his public.' For the first time, it drew attention to a group of collectors and connoisseurs of the late seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries who had viewed Vermeer not as a "sphinx" but a first-class painter."Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., exh. cat. Johannes Vermeer, eds. Wheelock and Broos (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

1930–1940

Oil on canvas, 58 x 47cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In the latter half of the twentieth century, Vermeer's painting was reexamined in a more objective light. As a result, the personal intuition of a trusted "experts" is no longer considered a reliable basis for evaluating the work of such a complex painter as Vermeer. His entire oeuvre is now studied in relation to his contemporary social and artistic milieu and through the understanding of the contemporary iconography which is generally believed to have played a fundamental role in Dutch painting. Laboratory analysis has also become an integral part of understanding Vermeer's and Dutch seventeenth-century painting as well.

Who was Han van Meegeren?

Henricus Anthonius van Meegeren was born in Deventer in1889 as the third child of Roman Catholic parents. His father sent him to the Delft Institute of Technology in order to be trained as an architect. However, Van Meegeren soon discovered a love for art and made such significant progress that he quickly became the teaching assistant in the departments of Drawing and History of Art. He won a gold medal for a drawing of a church interior done in the seventeenth-century style already demonstrating his talent for imitation. After having married Anna de Voogt (who later bore him two children - Jacques and Pauline) he began to show his first paintings with some success in an exhibition in Kunstzaal Pictura, Den Haag.

Then his problems began, Van Meegeren began drinking. In 1921, he spent three months traveling in Italy presumably to study the Italian masters and in 1922 he held an exhibition of paintings, which were all sold, of Biblical themes in Kunstzaal Biesing, The Hague. In 1923 he officially divorced Anna van Voogt.

1927 Van Meegeren's The Deer was the most valued painting at a lottery of the Haagsche Kunstkring. Shortly after he married the actress Jo Oerlemans, who was formerly married to the art critic C.H. de Boer.

Van Meegeren regularly contributed articles for De Kemphaan, a monthly art magazine founded in 1928 which opposed progressive art movements. He also designed the magazine's cover. However, the magazine was closed only two years later. When Van Meegeren moved to Roquebrune, in the south of France, he was probably thoroughly convinced that there was no longer any possibility that his talent would ever be recognized by the art establishment. In order to vindicate himself in the art world, Van Meegeren began working on a series of forgeries. As a kind of warm-up exercise, he first produced four unsold paintings in seventeenth-century style: A Guitar Player and A Woman Reading Musician Vermeer's style, A Woman Drinking, in Frans Hals' style and A Portrait of Man in Ter Borch's style. Once Van Meegeren had gained confidence, he painted Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus, probably the best of all his forgeries.

In September 1937, Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus was identified by Bredius as a masterpiece by Vermeer of Delft. Bredius contended that Vermeer had been influenced by Italian painting and Van Meegeren's forgery was especially welcomed as it supported this theory; exactly what Van Meegeren had hoped for. At first, Van Meegeren wanted to reveal the fraud—especially because he despised in particular Bredius—but when he sold the fake Vermeer for the equivalent of what would now be several million dollars, he unsurprisingly had second thoughts. He had proven to his own satisfaction that the Dutch art establishment was ignorant, and that would have to do as long as he could make good money. Scarcely one year later the painting was officially delivered to Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, purchased with financial donations of the Stichting Rembrandt, the Rotterdam ship-owner W. van der Vorm, Bredius and a few Rotterdam private collectors. Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus soon became the museum's top attraction.

In the summer of 1938 Van Meegeren, spurred by the overwhelmingly enthusiastic reception of his work, moved to Nice and painted The Card Players and The Drinking Party in the style of Pieter de Hooch. In 1939 this last painting is sold to D.G. van Beuningen.

Over a seventeenth-century painting of Govert Flinck, Van Meegeren painted The Last Supper in the style of Vermeer but due to the threat of war, he returned to Holland leaving the painting behind in Nice. From 1941 to 1943, the year in which he divorced his second wife, Van Meegeren continued to produce Vermeer forgeries. In 1943, he sold the Christ and the Adulteress sold to Field-Marshal Hermann Goering in exchange for two hundred Dutch paintings which the Nazis had plundered early in the war. One of Van Meegeren's forgeries was sold in 1942 for the 1.6 million Dutch guilders, making it one of the most expensive paintings ever sold.

In 1945, May Captain Harry Anderson discovered Christ and The Adulteress in Goering's personal art collection and soon traced to painting to Van Meegeren.

Van Meegeren was arrested and charged with collaboration for having sold an authentic "Vermeer" to Goering. After two weeks of imprisonment, Van Meegeren on June 12 revealed that he could not be accused of collaborationb becasue he had himself painted the painting in question. After being detained in prison for six week, he was placed in a house rented by the Dutch government, and there he began to paint for the benefit of the court authoritie his last "Vermeer," Jesus amongst the Doctors.

In November of 1947, Van Meegeren was convicted to one year in prison. One month later, at the age of 58, he fell ill due to years of drug and alcohol abuse and died of a heart attack in prison. In 1950 household effects were auctioned in his house at 321 Keizersgracht in Amsterdam (fig. 6) .

In all, he made more than seven million guilders, about $2 million then and roughly about twenty times that amount today. In his last years, Van Meegeren lived the high life and had purchased a number of houses (fig. 5) until he was caught.

Essential Bibliography

- Bredius, Abraham. "A New Vermeer." Burlington Magazine 71 (November 1937): 210–211.

- Bredius, Abraham. "An Unpublished Vermeer." Burlington Magazine 61 (October 1932): 145.

- Coremans, P.B. Van Meegeren's Faked Vermeers and de Hooghs. Translated by A. Hardy and C. Hutt. London: Cassel, 1949.

- Dolnick, Edward. The Forger's Spell: A True Story of Vermeer, Nazis, and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieth Century. New York: Harper Perennial, 2009.

- Godley, John. Van Meegeren, Master Forger. New York: Scribner, 1967.

- Jones, Mark. Fake? The Art of Detection. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- Lammertse, E. Van Meegeren's Vermeers - The Connoisseurs Eye And The Forger's Art. Rotterdam: Boijmans Van Beuningen, 2011.

- Lopez, Jonathan. The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren. 2008.

- Ragai, Jehane. The Scientist and the Forger: Insights into the Ancient Scientific Detection of Forgery in Paintings. London: Imperial College Press, 2015.

- Tietze, Hans. Genuine and False. London: Max Parrish & Co, 1948.

- Werness, Hope B. "Han van Meegeren fecit." In Denis Dutton, ed., The Forger's Art: Forgery and the Philosophy of Art. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

- Wynn, Frank. I Was Vermeer: The Rise and Fall of the Twentieth-Century's Greatest Forger. London: Bloomsbury Press, 2006, 2007.

List of known forgeries by Han van Meegeren

- A counterpart to Laughing Cavalier after Frans Hals (1923) once the subject of a scandal in The Hague in 1923, its present whereabouts is unknown.

- The Happy Smoker after Frans Hals (1923) hangs in the Groninger Museum in the Netherlands

- Man and Woman at a Spinet 1932 (sold to Amsterdam banker, Dr. Fritz Mannheimer)

- Lady reading a letter, 1935–1936 (unsold, on display at the Rijksmuseum.)

- Lady playing a lute and looking out the window] 1935–1936 (unsold, on display at the Rijksmuseum.)

- Portrait of a Man, 1935–1936 in the style of Gerard ter Borch (unsold, on display at the Rijksmuseum.)

- Woman Drinking (version of Malle Babbe) 1935–1936 (unsold, on display at the Rijksmuseum.)

- The Supper at Emmaus, 1936–1937 (sold to the Boymans for 520,000–550,000 guldens, about $300,000 or $4 Million today)

- Interior with Drinkers 1937–1938 (sold to D G. van Beuningen for 219,000– 220,000 guldens about $120,000 or $1.6 million today)

- The Last Supper I, 1938–1939

- Interior with Cardplayers 1938 - 1939 (sold to W. van der Vorm for 219,000–220,000 guldens $120,000 or $1.6 million today)

- The Head of Christ, 1940–1941 (sold to D G. van Beuningen for 400,000 – 475,000 guldens about $225,000 or $3.25 million today)

- The Last Supper II, 1940–1942 (sold to D G. van Beuningen for 1,600,000 guldens about $600,000 or $7 million today)

- The Blessing of Jacob 1941–1942 (sold to W. van der Vorm for 1,270,000 guldens about $500,000 or $5.75 million today)

- Christ with the Adulteress 1941–1942 (sold to Hermann Göring for 1,650,000 guldens about $624,000 or $6.75 million today, now in the public collection of Museum de Fundatie)

- The Washing of the Feet 1941–1943 (sold to the Netherlands state for 1,250,000 – 1,300,000 guldens about $500,000 or $5.3 million today, on display at the Rijksmuseum.)

- Jesus among the Doctors September 1945 (sold at auction for 3,000 guldens, about $800 or $7,000 today)

- The Procuress given to the Courtauld Institute as a fake in 1960 and confirmed as such by chemical analysis in 2011.

Thefts, forgeries & the Van Meegeren case

The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren

The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van MeegerenJonathan Lopez

2009

The Forger's Spell: A True Story of Vermeer, Nazis, and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieth Century

The Forger's Spell: A True Story of Vermeer, Nazis, and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieth CenturyEdward Dolnick

2009