The Little Street

c. 1657–1661Oil on canvas

54.3 x 44 cm. (21 3/8 x 17 3/8 in.)

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Where is location of Vermeer's Little Street?

Although many locations have been proposed in the past, the most consistent candidate for the location of the scene of Vermeer's Little Street has been the Voldersgracht, a narrow street that runs next to a canal in the center of Delft, where Vermeer was born. However, some art historians believe that despite the scene's realistic appearance, it could be a distillation of typical architectural elements gathered and adroitly woven together within the privacy of the artist's studio.

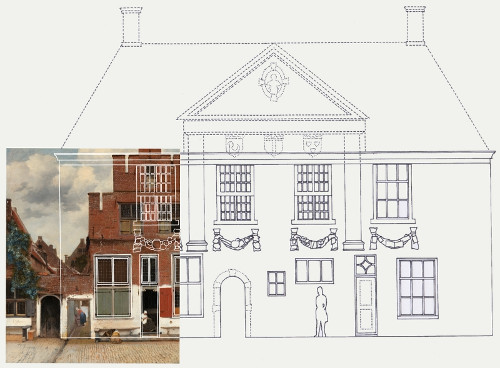

The century-old question has been recently addressed by Dr. Frans Grijzenhout, professor of Art History at the University of Amsterdam. Grijzenhout argues that the setting for painting is on Vlamingstraat (fig. 1) in Delft, where houses 40–42 now stand. Grijzenhout's conclusion is based on measurements he has found in the Legger van het diepen der wateren binnen de stadt Delft (Ledger of the dredging of canals in the town of Delft), a document compiled from 1666 onward recording the widths of house frontages for tax purposes.

However, Philip Steadman, the London architect and author of Vermeer's Camera: Uncovering the Truth behind the Masterpieces, examined point for point Grijzenhout hypothesis and found a number of inconsistencies. Steadman holds that Grijzenhout's proposal is unfounded and provided detailed information in support of the Voldersgracht.

Click here to read Steadman's arguments supported with contemporary maps, drawings and a 19th century photograph.

Grijzenhout mused that the house on Vlamingstraat would have had particular resonance for Vermeer, since the house was occupied at this date by Ariaentgen Claes van der Minne, one of Vermeer's aunts. But Steadman suggests that Voldersgracht would have held greater meaning for the painter in that it was a view from his family home, across to a building, which, when he painted The Little Street, was just about to be converted for use by his profession's center, the Guild of Saint Luke (fig. 2).

Het Straatje—'The Little Street'—is in fact a little painting of a small section of street. There is nothing to indicate how wide the street is, though we get the impression that the painter's view (which is our view) is from a house apposite, from an upstairs room, at no great distance. Topographical experts and local historians in Delft have spent much time trying to pin down where this was. The Oude Langendijk, the Nieuwe Langendijk, the Trompetstraat, the Spieringstraat, Achterom, the Vlamingstraat, and the Voldersgracht are among the numerous streets put forward for the honour. The Voldersgracht has been a consistent candidate, for the back of Mechelen overlooked the little canal of the Voldersgracht and its narrow carriageway, on to which faced the Old Men's Home and—a few doors further east—the Flying Fox inn. In a few years the Old Men's Home was going to be partly rebuilt, with its chapel converted in 1661 into the hall of the Guild of Saint Luke; drawings of the hall show a small house and archway similar to the part of the left-hand house and archway depicted in The Little Street. But the house on the right in that picture has its gable-end facing the street, while the building which housed the chapel of the Old Men's Home stood side-on to the street. The two arched outside doorways in the painting, one with a closed door, the other with door open revealing a brick-paved passage in which a servant-woman is leaning aver a barrel used as a washtub or cistern, and waste water runs towards us along a gulley form the heart of the picture (fig. 3). What is behind the dark closed door? Its shut state, the openness and light of its companion, bring to mind those weather-predicting devices styled as miniature cottages out of which figures swing to declare that it is going to be fine or rainy.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1660–1663

Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 117.5 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

There must have been many hundred such passageways in Delft then. However, an adjacent pair, with twin gates like those in the picture, is now not to be found in any of the favoured streets. But given the artist's close relationship with Van Ruijven, it seems a possibility that the house on the right belonged to that gentleman. The Little Street was painted around the time Vermeer and his wife borrowed 200 guilders from Van Ruijven. The house on the right has signs of a good deal of hasty repainting and patching of cracks, as if it was shaken severely by the Thunderclap, and we know that Van Ruijven owned a house on the east side of the Voorstraat that was damaged in the explosion. The picture was in his collection.

For all that, it also seems probable that here, as in many other paintings, Vermeer picked and mixed his details. He took some elements of reality and put them together in an 'invented' scene; he may have observed some details and remembered or imagined others. When we look closely at it, the main house in The Little Street is a strange mish-mash of architectural features, to which an air of plausibility is given by the wonderful painting of brick, wood, and glass, of the trees and sky, and of the figures of the two women and two children. The front doorway, in which one of the women sits sewing (fig. 4), is not quite in the centre of the facade, as might be expected, but is offset to the left. Did Vermeer piece it there to accommodate the swung-open shutter on the right with its vivid rectangle of red? And what about its partners, the closed green shutters on the left of the doorway? The right-hand one of those would be impossible to open, at least with abandon, all the way, without partly obstructing the front doorway. A further impracticality in terms of sound building practice is to be seen in the position of this left-hand ground-floor window. It immediately abuts the side wall of the house. The shallow arch of bricks above its wooden lintel presses against the very edge of this wall, and few Dutch builders would have risked their reputations—or the lives of the children playing under the wall-hung bench—with such a construction. The house wouldn't stand up to a good push, let alone a gunpowder explosion.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1660–1663

Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 117.5 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

For Vermeer, form clearly preceded function. He has apparently taken various details from various houses (maybe more from one than from others) and stuck them together, as if with the tie-rods and mortar that make us believe we are looking at an 'actual' streetscape. The leaves of the vine that is growing up the wall of the cottage on the left, the rough bricks, the places where ridge-tiles are missing over the passage entries, and the weathered in-need-of-attention framing of the windows are painted with such a light, almost pointillist touch that we are seduced into feeling that all this has been rendered with utter verisimilitude. The liberties he has taken include theft, or at least major borrowing, from fellow artists. The Ville, passageway, and servant-woman are more than somewhat de Hooch, while the beautifully observed children crouching on their knees are extremely similar to the children in a 1650 Houckgeest painting of the interior of the Nieuwe Kerk and William the Silent's tomb. And yet! -and yet the ultimate effect is original. The painting is an elegy for a moment which—unless Vermeer had captured it—would have slipped away for ever: the women busy with their chores, the children entranced by their game, the clouds filtering the sunlight, two doors and one window open, and air wafting through the house.

Time, halted for this instant and therefore in a sense for eternity, seems to be his essential subject. Its wear and tear is visible in the bricks and mortar, the fabric of fact that bluntly underpins our tenuous and temporary hold on existence with its many unanswerable questions, such as 'What are we doing here?'

Walfigureter Liedtke

Vermeer and the Delft SchoolNew York, 2001, pp. 374–376

Rembrandt van Rijn

1654

Oil on canvas, 112 × 102 cm.

Six Collection, Amsterdam

Since at least the 1860s, when "half of Europe" began visiting the private museum of the Six family (fig. 5) in Amsterdam, this painting has been one of the defining images of Delft, one of Vermeer's best known and least typical pictures, although Sir John Murray, in 1823 (forty years before Thoré- Bürger discovered Vermeer), said of the canvas, "The whole is touched with that truth and spirit which belong only to this master"

Without disputing Murray's sentiment, it may be said no painting by Vermeer reveals a sympathetic response to the work of Pieter de Hooch quite so clearly as this one. De Hooch painted a fair number of courtyard and related views, drawing upon Delft motifs, from about 1657 onward. These pictures celebrate the virtues of domestic life, a theme almost untouched by Vermeer while exploring the picturesque possibilities of narrow streets, alleys, courtyards, and closely clustered houses, like those to the west of the Oude Delft, where De Hooch lived at the time. Vermeer brought his own design sensibility to the subject, but his view of an old house (the facade would date from about 1500) (fig. 6), evidently from across a canal, is strongly reminiscent of De Hooch in a number of details and to some extent in the composition as a whole.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1660–1663

Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 117.5 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

For example, in De Hooch's early courtyard scene in Toledo (fig. 7), the composition is divided similarly into sections representing the rear of a house, the pavement, the white-washed brick wall of the courtyard, and a view of rooftops and sky. The maid to the left occupies a pivotal place in the arrangement, as does Vermeer's maid in the alley (not withstanding her small scale). Analogous compositions had been painted somewhat earlier by Gerrit ter Borch (The Grinder's Family (fig. 9) of about 1653, in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) and by Carel Fabritius, but De Hooch developed the type much further on his own and also depicted interiors that are closely related in subject and design. In 1658 he began to favor frontal designs relieved by views through doorways, as in the courtyard scenes in the National Gallery, London, and in a private collection in A Dutch Courtyard (fig. 8), and in several similar pictures (compare the slightly later Woman and a Maid in a Courtyard with the panel in Toledo and with The Little Street).

in a Courtyard

Pieter de Hooch

c. 1657

Oil on canvas, 68 x 57.4 cm.

Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo (OH)

Pieter de Hooch

c. 1660

Oil on canvas, 73.7 x 62.6 cm.

National Gallery, London

Gerrit ter Borch

1653–55

Oil on canvas, 74 x 61 cm.

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Berlin

The taste for such orderly compositions clearly developed in good part from genre interiors by Ludolf de Jongh and by De Hooch himself, and before them by Hendrick Sorgh, Nicolaes Maes and others. But De Hooch greatly enriched the trend by bringing to it all the humble embellishments that age, weather, and vegetation had to offer. Here, too, there were many precedents, in pictures of inns and farmhouses by Isack van Ostade, in stable scenes by Potter (in peasant houses depicted by Egbert van der Poel, and in many other works. But in De Hooch's oeuvre and, one he is tempted to say, in Delft (on the strength of paintings by Potter, Pynacker, Fabritius, Van der Poel, Vermeer, and Daniel Vosmaer; as well as by De Hooch)—these naturalistic incidents were carefully combined with a Dutch version of classical design. The synthesis achieved a quite deliberate aesthetic effect and was adopted not only by Vermeer but also by Hendrick van der Burch, Daniel Vosmaer, and even Van der Poel. Of course, such a historical sketch reduces to a simple scheme the in consequences of taste, intuition, and as many accidents as one finds in all the brick walls and cobblestones or De Hooch and Vermeer.

Vermeer would have been the first to recognize the wonderful effects of space, light, color, and texture in De Hooch's exterior views of about 1658. These are for the most part surpassed in The Little Street which should be understood (as with Vermeer's responses to Ter Borch and Frans van Mieris) as a tribute to the slightly older artist, an instance of local aemulatio. The extraordinary passages of description (and of observation; in the case of details the painter actually saw) could be discussed for hours, time better spent in front of the picture itself. It is only there that one can appreciate how, despite superbly impressionistic effects (for example, in the rooftops to the left, the ivy, and the watery cobblestones), it would be utterly mistaken to speak of glossed-over details. One might consider what could have been done with the doorframe around the alleyway, or with the pair of green shutters, which exhibit well-worn edges and surfaces, and gaps that allow them to sink into the wall.

Here in a subject that could have been treated in terms of solids and space is an essay that is, weeks of work devoted to inflections of color and light, which have multiplied beyond the realms of costume, table-carpets, wall maps, and bread with the motifs in this picture: above all, mortar and brick but also lacelike leaded windows, linen-like whitewashed walls (a simile tested at the entrance of the house) and woolly walls and roof tiles. It is to this painterly end, not because of any optical instrument (eyes aside), that the depth of three houses on the left five gables and a farther chimney fall into view is treated like so many trees in the distance. This approach was continued in A View of Delft, which probably dates from slightly later, about 1660–1661. Both pictures appear to have been owned by Vermeer's principal patron in Delft, Pieter van Ruijven, who also had three church interiors by Emanuel de Witte in his collection.

Of course, there is more to The Little Street than the attractive surfaces of a familiar world. For once Vermeer adopts a De Hooch-like theme: a family home, long cared for, the timeless routines of household work; and the blessing of children, who will, it is hoped, grow to maturity and leave the house to children of their own.

Vermeer appears to have combined and modified motifs taken from different houses in Delft, as De Hooch did in his courtyard views. The connection with those compositions is underscored again (if faintly) by the pentimento of a woman sitting in the doorway of the alley. The motif recalls the little girl in the doorway in one of De Hooch's two courtyard views dated 1658, while the similar painting in London could have suggested to Vermeer the deeper placement of the maid. But his wide knowledge of what other artists had done and his possible sources in actual architecture cannot be combined in some simple equation to explain how this painting about. Vermeer creates the impression, at once false and true, that he surveyed all the latest pictorial ideas and then put them aside, turning to a view out the window.

One side of the house looked out on to the Voldersgracht and the municipal home for old people. Standing at one of the windows of his home, Vermeer painted the view of the houses opposite. The Street in Delft was thus painted in a room, but is a view of the world outside; in fact it is the earliest of all plein-air paintings. The Dutch landscape-painters must certainly have often worked in the open air, but all their pictures have the values of interiors, and that is true of Rembrandt, Ruisdael, Hobbema and De Hooch. Vermeer is an exception, and even in his interiors he comes very close to plein-air painting, except that his treatment of light invariably has only one direction.and we never find diffused light in his pictures. Nor do we find in his works that use of light and shade for purposes of contrast and as expressive values which was so frequent in Baroque painting. Vermeer evolved a simple and ingenious solution: broad daylight; and a modulation of this which, according to whether it contains more or less light, does not define the individual forms everywhere and at every place, but shows how light and objects encounter one another and how they become spatially visible.