c. 1660–1663

Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 117.5 cm.

Mauritshuis<, The Hague

Marcel Proust's À la recherche du temps perdu (fig. 1) Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past, 3 vols., trans. C. K. Scott Moncrieff, T. Kilmartin, and A. Mayor (New York, 1982). contains a well-known passage in which the elderly writer BergotteAnatole France (1844–1924), a French poet, journalist, and novelist with several best-sellers, is widely believed to be the model for Bergotte in Proust's Remembrance of Things Past. visits a Dutch art exhibit and, while examining a detail of Vermeer's View of Delft, falls ill, and dies. That scene, that painting, that detail have attracted the attention of a multitude of critics: Bergotte's final thoughts before dying perhaps more than any other faithfully reflect Proust's idea of art. But which part of Vermeer's View of Delft, if any, picture corresponds to the noted "petit pan de mur jaune"This passage is often cited as an example of Proust's ability to explore the intricate connections between art, perception, and personal memory. Proust appreciated Vermeer's ability to find beauty in ordinary, everyday scenes. He saw in Vermeer's work an affirmation of the idea that the mundane could be elevated to the level of art, mirroring Proust's own examination of the significance of seemingly trivial moments in life.?

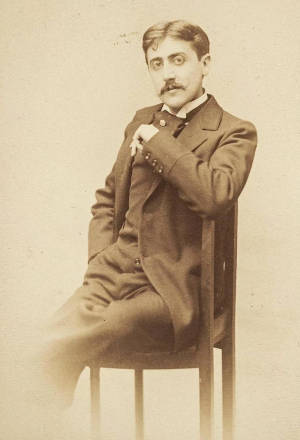

Towards the end of his fifty-one years of life, Proust told the writer Jean-Louis Vaudoyer (1883–1963) that Vermeer had been "my favorite painter since the age of twenty." In September 1902, when he was thirty-one, Proust read Eugène Fromentin's (1820–1876) Les Maîtres d'autrefois and traveled to Bruges, Antwerp, and Amsterdam, then went to Dordrecht and Delft. There he saw "an ingenuous little canal, bewildered by the din of seventeenth-century carillons and dazzled by the pale sunlight; it ran between a double row of trees stripped of their leaves by summer's end, and stroking with their branches the mirroring windows of the gabled houses on either bank." On October 18, he moved on to The Hague where he saw the View of Delft and "recognized it for the most beautiful picture in the world."

"Through Vermeer Proust meditated his own end. In May 1921, the exhibition of Dutch painting at the Jeu de Paume (Exposition hollandaise. Tableaux, aquarelles et dessins anciens et modernes) (fig. 2).The 1921 exhibition of Dutch painting at the Jeu de Paume in Paris was a significant event in the world of art. This exhibition, officially titled "Exposition hollandaise. Tableaux, aquarelles et dessins anciens et modernes," showcased a remarkable collection of Dutch artworks spanning various periods and styles. The exhibition aimed to introduce French audiences to the rich history of Dutch art, from the early masters to modern painters. It sought to highlight the diverse and influential contributions of Dutch artists to the world of painting. The exhibition featured works from the Dutch Golden Age, which included paintings from the seventeenth century, as well as more contemporary Dutch artists. Visitors had the opportunity to see pieces by renowned Dutch painters like Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Hals, alongside works by modern Dutch artists. Vermeer was among the most talked about, painters despite only three canvases being exhibited: View of Delft, The Milkmaid, and Girl with a Pearl Earring. The attention of the Parisians was all for the latter, reproduced in the catalogue and in periodicals (the same effect would be produced at the Galleria Borghese in 1928).. was attracting crowds, drawn to see among other things, Vermeer's View of Delft and Girl with a Pearl Earring. According to George Painter's biography of him,George D. Painter and Samuel H. Bryant, Proust: Biography of French Novelist, Essayist, and Critic Marcel Proust (Little, Brown, 1959). Proust had read in the Paris press articles on the Vermeers by Lèon Daudet (1867–1942) and Jean-Louis Vaudoyer (1883–1963). At last he decided he had to go and see them. At nine one morning, a time when he is usually just going to sleep, Proust sent a message to Vaudoyer asking him to accompany him to the Jeu de Paume. Leaving the apartment he had a terrible attack of giddiness, recovered from it, and went on downstairs. At the exhibition, Vaudoyer steadied the writer's shaky progress towards the View of Delft. Proust was apparently revived by Vermeer, for he managed to go on to the Ingres exhibition and then to lunch at the Ritz before returning home, though according to Painter he was still "shaken and alarmed" by the attack. He never went out again. Proust soon transmuted this experience into the La Prisonnière (The Captive), the fifth part of À la recherche du temps perdu, to which he was still making changes. His character Bergotte, a writer, had been ill. Bergotte slept badly, had nightmares and couldn't write anymore. But he had read in a newspaper that the View of Delft was to be seen in Paris, a painting he adored and imagined he knew by heart, though the article had referred to 'a little patch of yellow wall' in the picture as being like a 'priceless specimen of Chinese art, or a beauty that was sufficient in itself' and worryingly he couldn't recall that particular patch."Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft, New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2001, 248–249.

Marcel Proust

Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1914

[preface by Léonce Bénédite]

The Hague : Mouton & Cie, 1921

The supposed identity of Proust's little patch of yellow wall in Vermeer's View has been analyzed by a number of literary and painting critics but surprisingly, there is no consensus on just which area the French writer had in mind. A few of their ideas are reported below.

Lorenzo Renzi, who has published a fascinating and scrupulous analysis of the argument (Proust and Vermeer: An Apology for Imprecision, 1999)Lorenzo Renzi, Proust and Vermeer: An Apologia dell'Imprecisione (Bologna: Il Mulino, 1999). maintains that, in effect, Proust had not indicated any specific point of the View of Delft, but rather an expressive composite of past literary experience and direct observation of the painting. In any case, Renzi's volume can be read with profit by anyone who is interested in Vermeer or Proust (click here for an exclusive interview with the author).

Where is the "petit pan de mur jaune"?Some of the ideas found in this page have been drawn from Proust and Vermeer: An Apologia dell'Imprecisione, Lorenzo Renzi, Bologna: Il Mulino, 1999.

How is the little patch described?

…it is a little wall;

…its color is yellow;

…it is with a sloping roof;

…it is precious like a work of Chinese art.

Two or perhaps three areas are usually taken into consideration. One, to the left of the Rotterdam Gate indicated as area "A," another larger at the extreme right-hand border of the painting indicated as area "C" and a smaller indicated by "B" (fig. 3).

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1660–1663

Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 117.5 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

George D. Painter

Marcel ProustGeorge D. Painter and Samuel H. Bryant, Proust: Biography of French Novelist, Essayist, and Critic Marcel Proust (Little, Brown, 1959).

Painter is the first to mention the "petit pan de mur jaune." He believes that it is at the extreme right of the painting "in reality, where the 'petit pan de mur jaune' is found, or rather the pieces, because there were more than one, on the extreme right one cannot see a roof but the upper part of a drawbridge with parts of parallel wooden beam."

This description corresponds to the area marked "C" on the image above.

Jeffrey Mayers

"Proust and Vermeer," in Art InternationalJeffrey Mayers, "Proust and Vermeer," Art International 1973, 68.

Mayer believes that "the famous little patch of roof (not wall) that the writer Bergotte sees in a moment of epiphany before his death appears just next to the pointed left turret of the Rotterdam gate, amid the warm browns and blues of the stone buildings and tiled roofs, and it provides a golden contrast to the rich red roofs on the right side of the painting."

This description corresponds to the area marked "A" on the image above.

Jean Pavans

Les écarts d'un vision, in Marcel Proust, Petit pan de mur juane d'après la vue de Delft de VermeerJean Pavans, "Petit pan de mur jaune, d'après Vermeer de Delft" (Collection "Tableaux vivants"; Paris: Editions de la Différence, 1986).

According to Pavans, "petit pan de mur jaune" indicates "not the splendid yellow roof, the only one which would merit a literary celebrity but rather, another detail less splendid, the sober wall at the extreme right.

This description corresponds to the area marked "B" on the image above..

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr.

Vermeer and the Art of PaintingArthur K. Wheelock Jr., Vermeer and the Art of Painting (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 77.

"the yellow roof above the Rotterdam gate, the one that Proust so admired was first painted a salmon color similar to one Vermeer used in the distant rooftops. The dense yellow layer with which he covered it is similar in texture to that of the Nieuwe Kerk."

This description corresponds to the area marked "A" on the image above.

Lorenzo Renzi

Proust e Vermeer: Apologia dell'ImprecisioneLorenzo Renzi, Proust and Vermeer: An Apologia dell'Imprecisione (Bologna: Il Mulino, 1999), 61.

According to Renzi, "the elements of the View of Delft that, as suggested in the reading of the article, attract Bergotte, do not seem clearly individuated and above all they do not concord with one another: if the little wall which is delicately "Chinese" is the one to the right, its color, without doubt, must be attributed to the sun-filled roof, the preciousness would belong to the luminous points of light of the boats and the walls. The only attribute that is almost certain, but which in any case seems to lack "Chinese preciousness," would be the sunlight roof. So what in Proust has been unified in a single detail, in Vermeer's painting is strewn out over the whole painting."

An exclusive interview with Prof. Renzi about this argument can be accessed by clicking here.

Carter believes that from what can be understood of original text, neither areas of the two most often cited are more strongly probable than the other and that Proust is creating an impression rather than sending us to admire a precise detail in the painting.Personal communication with the author.

Jean-Yves Tadié

Marcel Proust: A Biography,Jean-Yves Tadié, Marcel Proust: A Biography (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2000).

Tadié identifies the "petit pan de mur jaune" with an apparently insignificant wall to the extreme right of the painting.

This description corresponds to the area marked "B" or "C" on the image above.

La Pléiade

(latest French edition: end of note 2 to page 692)

"The little patch of yellow wall is at the extreme right of the painting." "In fact, there where the little patch of yellow wall is, or rather the patches of yellow wall because there are several of them, at the extreme right of the painting there is no sloping roof but the upper part of a drawbridge with identical pieces of wood."

This description corresponds to the area marked "C" on the image above.

When did Proust Write the Death of Bergotte?

Thanks to Chris Herman for providing this information.On page 150 of the Edmund White biography of Proust (Penguin 1999) it states that: "Indeed, on the night before he died Proust dictated a last sentence, "There is a Chinese patience in Vermeer's craft."

The Tadie biography (originally Editions Gallimard 1996, published in the US by Penguin 2001) differs and seems to state that it was not written on his last night and even that Proust was quoting that line from an article about the exhibition published on May 14 by Jean-Louis Vaudoyer.

Tadie says the following about Proust's last night:

"And during the night, he dictated some sentences to do with Bergotte's death: a partially incoherent passage, into which he put himself, and he described the activity of the doctors dancing attendance on the dying man."

Grave of Marcel Proust at

Grave of Marcel Proust at The Death of Bergotte

by Marcel Proust

I learned that a death had occurred that day which distressed me greatly—that of Bergotte. It was known that he had been ill for a long time past. Not, of course, with the illness from which he had suffered originally and which was natural. Nature scarcely seems capable of giving us any but quite short illnesses. But medicine has developed the art of prolonging them. Remedies, the respite that they procure, the relapses that a temporary cessation of them provokes, produce a simulacrum of illness to which the patient grows so accustomed that he ends by stabilising it, stylising it, just as children have regular fits of coughing long after they have been cured of the whooping cough. Then the remedies begin to have less effect, the doses are increased, they cease to do any good, but they have begun to do harm thanks to this lasting indisposition. Nature would not have offered them so long a tenure. It is a great wonder that medicine can almost rival nature in forcing a man to remain in bed, to continue taking some drug on pain of death. From then on, the artificially grafted illness has taken root, has become a secondary but a genuine illness, with this difference only, that natural illnesses are cured, but never those which medicine creates, for it does not know the secret of their cure.

For years past Bergotte had ceased to go out of doors. In any case he had never cared for society, or had cared for it for a day only, to despise it as he despised everything else, and in the same fashion, which was his own, namely to despise a thing not because it was beyond his reach but as soon as he had attained it. He lived so simply that nobody suspected how rich he was, and anyone who had known would still have been mistaken, having thought him a miser whereas no one was ever more generous. He was generous above all towards women—girls, one ought rather to say—who were ashamed to receive so much in return for so little. He excused himself in his own eyes because he knew that he could never produce such good work as in an atmosphere of amorous feelings. Love is too strong a word, but pleasure that is at all rooted in the flesh is helpful to literary work because it cancels all other pleasures, for instance the pleasures of society, those which are the same for everyone. And even if this love leads to disillusionment, it does at least stir, even by so doing, the surface of the soul which otherwise would be in danger of becoming stagnant. Desire is therefore not without its value to the writer in detaching him first of all from his fellow men and from conforming to their standards, and afterward in restoring some degree of movement to a spiritual machine which, after a certain age, tends to come to a standstill. We do not achieve happiness but we gain some insights into the reasons which prevent us from being happy and which would have remained invisible to us but for these sudden revelations of disappointment.

Dreams, we know, are not realisable; we might not form any, perhaps, were it not for desire, and it is useful to us to form them in order to see them fail and to learn from their failure. And so Bergotte said to himself: "I spend more than a multimillionaire on girls, but the pleasures or disappointments that they give me make me write a book which brings me in money." Economically, this argument was absurd, but no doubt he found some charm in thus transmuting gold into caresses and caresses into gold. We saw, at the time of my grandmother's death, how a weary old age loves repose. Now in society there is nothing but conversation. Vapid though it is, it has the capacity to eliminate women, who become nothing more than questions and answers. Removed from society, women become once more what is so reposeful to a weary old man, an object of contemplation. In any case, now there was no longer any question of all this. I have said that Bergotte never went out of doors, and when he got out of bed for an hour in his room, he would be smothered in shawls, rugs, all the things with which a person covers himself before exposing himself to intense cold or going on a railway journey. He would apologise for them to the few friends whom he allowed to penetrate to his sanctuary; pointing to his tartan plaids, his travelling-rugs, he would say merrily: "After all, my dear fellow, life, as Anaxagoras has said, is a journey." Thus he went on growing steadily colder, a tiny planet offering a prophetic image of the greater, when gradually heat will withdraw from the earth, then life itself. Then the resurrection will have come to an end, for, however far forward into future generations the works of men may shine, there must none the less be men. If certain species hold out longer against the invading cold, when there are no longer any men, and if we suppose Bergotte's fame to have lasted until then, suddenly it will be extinguished for all time. It will not be the last animals that will read him, for it is scarcely probable that, like the Apostles at Pentecost, they will be able to understand the speech of the various races of mankind without having learned it.

In the months that preceded his death, Bergotte suffered from insomnia, and what was worse, whenever he did fall asleep, from nightmares which, if he awoke, made him reluctant to go to sleep again. He had long been a lover of dreams, even bad dreams, because thanks to them, thanks to the contradiction they present to the reality which we have before us in our waking state, they give us, at the moment of waking if not before, the profound sensation of having slept. But Bergotte's nightmares were not like that. When he spoke of nightmares, he used in the past to mean unpleasant things that happened in his brain. Latterly, it was as though from somewhere outside himself that he would see a hand armed with a damp cloth which, rubbed over his face by an evil woman, kept trying to wake him; or an intolerable itching in his thighs; or the rage—because Bergotte had murmured in his sleep that he was driving badly—of a raving lunatic of a cabman who flung himself upon the writer, biting and gnawing his fingers. Finally, as soon as it had grown sufficiently dark in his sleep, nature would arrange a sort of undress rehearsal of the apoplectic stroke that was to carry him off. Bergotte would arrive in a carriage beneath the porch of Swann's new house, and would try to get out. A shattering attack of dizziness would pin him to his seat; the concierge would try to help him out; he would remain seated, unable to lift himself up or straighten his legs. He would cling to the stone pillar in front of him, but could not find sufficient support to enable him to stand.

The circumstances of his death were as follows. A fairly mild attack of uraemia had led to his being ordered to rest. But, an art critic having written somewhere that in Vermeer's `View of Delft' (lent by the Gallery at The Hague for an exhibition of Dutch painting), a picture which he adored and imagined that he knew by heart, a little patch of yellow wall (which he could not remember) was so well painted that it was, if one looked at it by itself, like some priceless specimen of Chinese art, of a beauty that was sufficient in itself, Bergotte ate a few potatoes, left the house, and went to the exhibition. At the first few steps he had to climb, he was overcome by an attack of dizziness. He walked past several pictures and was struck by the aridity and pointlessness of such an artificial kind of art, which was greatly inferior to the sunshine of a windswept Venetian palazzo, or of an ordinary house by the sea. At last he came to the Vermeer which he remembered as more striking, more different from anything else he knew, but in which, thanks to the critic's article, he noticed for the first time some small figures in blue, that the sand was pink, and, finally, the precious substance of the tiny patch of yellow wall. His dizziness increased; he fixed his gaze, like a child upon a yellow butterfly that it wants to catch, on the precious little patch of wall. "That's how I ought to have written," he said. "My last books are too dry, I ought to have gone over them with a few layers of colour, made my language precious in itself, like this little patch of yellow wall." Meanwhile he was not unconscious of the gravity of his condition. In a celestial pair of scales there appeared to him, weighing down one the pans, his own life, while the other contained the little patch of wall so beautifully painted in yellow. He felt that he had rashly sacrificed the former for the latter. "All the same," he said to himself, "I shouldn't like to be the headline news of this exhibition for the evening papers." He repeated to himself: "Little patch of yellow wall, with a sloping roof, little patch of yellow wall." Meanwhile he sank down on to a circular settee; whereupon he suddenly ceased to think that his life was in jeopardy and, reverting to his natural optimism, told himself: "It's nothing, merely a touch of indigestion from those potatoes, which were undercooked." A fresh attack struck him down; he rolled from the settee to the floor, as visitors and attendants came hurrying to his assistance. He was dead. Dead for ever? Who can say? Certainly, experiments in spiritualism offer us no more proof than the dogmas of religion that the soul survives death. All that we can say is that everything is arranged in this life as though we entered it carrying a burden of obligations contracted in a former life; there is no reason inherent in the conditions of life on this earth that can make us consider ourselves obliged to do good, to be kind and thoughtful, even to be polite, nor for an atheist artist to consider himself obliged to begin over again a score of times a piece of work the admiration aroused by which will matter little to his worm-eaten body, like the patch of yellow wall painted with so much skill and refinement by an artist destined to be for ever unknown and barely identified under the name Vermeer. All these obligations, which have no sanction in our present life, seem to belong to a different world, a world based on kindness, scrupulousness, self- sacrifice, a world entirely different from this one and which we leave in order to be born on this earth, before perhaps returning there to live once again beneath sway of those unknown laws which we obeyed because we bore their precepts in our hearts, not knowing whose hand had traced them there—those laws to which every profound work of the intellect brings us nearer and which are invisible only—if then!—to fools. So that the idea that Bergotte was not dead for ever is by no means improbable.

They buried him, but all through that night of mourning, in the lighted shop-windows, his books, arranged three by three, kept vigil like angels with outspread wings and seemed, for him who was no more, the symbol of his resurrection.