Girl with a Flute

c. 1665–1670Oil on panel, 20 x 17.8 cm. (7 7/8 x 7 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

acc. no. 1942.9.98

The textual material contained in the Essential Vermeer Interactive Catalogue would fill a hefty-sized book, and is enhanced by more than 1,000 corollary images. In order to use the catalogue most advantageously:

1. Scroll your mouse over the painting to a point of particular interest. Relative information and images will slide into the box located to the right of the painting. To fix and scroll the slide-in information, single click on area of interest. To release the slide-in information, single-click the "dismiss" buttton and continue exploring.

2. To access Special Topics and Fact Sheet information and accessory images, single-click any list item. To release slide-in information, click on any list item and continue exploring.

The flute

Judith Leyster

c. 1635

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

The recorder, commonly referred to as a flute, has a limited presence within Vermeer's body of work. Helen Hollis, a former member of the musical instruments division at the Smithsonian Institute, asserts that while the fipple mouthpiece is accurately depicted through the use of a double highlight, the alignment of the air hole beneath the mouthpiece is incorrect. This deviation becomes apparent when comparing the recorder hanging on the wall in Judith Leyster's painting, where it is positioned in alignment with the upper lip of the mouthpiece. The finger holes situated beneath the girl's hand deviate further from this alignment. This departure from alignment could be permissible if the recorder were constructed from two distinct sections.

Scientific analysis of the artwork unveils that the finger resting on the recorder was not executed by Vermeer's hand, suggesting the flute was not part of the original composition. Without the additional finger, the proper holding of the flute becomes implausible.

Whether the instrument's representation is precise or not, no one has put forth a feasible explanation for the juxtaposition of the young girl's Chinese hat and the instrument, assuming Vermeer indeed had an intention in mind for this combination.

The young girl

The identity of the androgynous girl remains unknown, yet her features bear resemblance to those of the Girl with a Red Hat, an artwork often regarded as a pendant by numerous experts. Within this present piece, the portrayal of the girl's face appears noticeably less refined than that of her counterpart. This divergence could be attributed to certain crucial portions of the painting being unfinished or subject to overpainting by another hand. The current depiction may be indicative of the so-called "working-up" phase, a common process that followed the initial monochromatic underpainting. Broad and simplified shifts of light and darkness establish both the anatomical characteristics and the play of light. Conceivably, certain rough transitions might have been softened using the "badger brush," or "sweetener," a fan-shaped brush employed not for direct application, but rather for seamlessly blending distinct tones.

However, what significantly robs the girl of her inherent expression has largely escaped the attention of most experts. Vermeer's skillful highlights, pivotal to the enigmatic depth of the Girl with a Red Hat, are entirely absent in this instance. This absence accounts for the atypical hazy aspect of the eyes and the lack of moisture in the lips. Typically applied in the final stages, highlights might be susceptible to overly enthusiastic restoration efforts. Considering all aspects, it would be unjust to pass judgment on the painting in its current state, which ranks among the least favorable among Vermeer's surviving 35 or 36 works.

One writer has discerned traces of Far Eastern influence not solely in the girl's distinct headwear, but also in her physiognomy. Nevertheless, even if Delft served as one of the gateways for Far East trade, an exotic hat does not inherently equate to an Oriental countenance. Ultimately, the girl, akin to numerous female subjects in Vermeer's oeuvre, possesses unassuming features that might escape casual notice if encountered on the streets. It is through the discerning gaze of the painter that they attain beauty.

The juxtaposition of the ordinary and extraordinary stands as one hallmark of the tronie genre (refer to the Special Topic box below). Irrespective of this, the girl's partially open mouth automatically excludes the work from being classified as a portrait, given that the depiction of teeth or the tongue was consistently avoided in true portraiture, arguably the most traditional facet of 17th-century artistry.

Certain writers posit that the girl could have been one of Vermeer's daughters, a possibility entirely plausible yet lacking any objective substantiation.

The girl's costume

The distinct attire in the painting shares similarities with the prevailing fashion of the period and appears to mirror Vermeer's affinity for satin and fur-adorned attire, frequently found in his depictions of everyday scenes. Although subject to partial repainting, the jacket bears resemblance to one worn by the singer in The Concert. This garment might correspond to the item referenced in Vermeer's probate inventory as "an old green mantle with white fur trimmings."

X-radiography and infrared reflectography provide insights indicating that the fur-trimmed front panel was not an original component of the attire. Vermeer subsequently incorporated this element during a later phase of the painting process, potentially enhancing the work's compositional arrangement. The fur trimming on the left-hand sleeve has been redone by a subsequent hand and lacks the vibrancy seen in the vertical panel and the right-hand sleeve. Technical analysis further demonstrates that the right-hand sleeve once extended further down the figure's forearm.

The bizarre hat

A Girl Drawing

follower of Frans van Mieris

1670s

Oil on panel

Private collection

The presence of such a bizarre hat might initially confound interpretation within Vermeer's visual repertoire, unless we acknowledge its potential connection to the likely pendant of the painting, Girl with a Red Hat, as well as the Dutch tronie tradition (refer to the Special Topic box below). Shared between these compositions, among other elements, is the presence of implausible headwear adorning an atypical countenance, an imaginative flourish that only a select cadre of painters could translate into remarkable artistry. The hat's wide brim casts a gentle shadow over the model's eyes, akin to the shading observed in Girl with a Red Hat. This technique had been employed by Rembrandt in a series of his early self-portraits, potentially accessible to Vermeer either directly or through numerous derivative works created by Rembrandt's apprentices.

The conical hat, though evocative of the contemporary fascination with Oriental attire, lacks a precise counterpart in Dutch paintings of that era. An expert contends that the parallel stripes on the hat do not adhere to the principles of perspective.

The lion-head finial

Detractors of the current artwork highlight the comparatively lower quality of the lion-head finial in contrast to that of Girl with a Red Hat, which could potentially be its pendant.

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., a noted authority on Vermeer, postulates that the lion-head finial might have been executed by a painter associated with the "circle of Vermeer," even though no concrete evidence supports the existence of such a circle or apprentices affiliated with Vermeer. Conversely, Walter Liedtke contends that, taking all factors into account, the work merits inclusion in Vermeer's body of work. He underscores that the piece exhibits numerous formal traits characteristic of paintings from the same era. The stylistic irregularities and less accomplished segments, he argues, stem from the piece being left incomplete by the artist.

The background tapestry

The backdrop tapestry constitutes another link binding this piece to Girl with a Red Hat. The tapestry in the background is rendered with an approximation that precludes definitive identification, despite the logical presumption that it likely belongs to the same category or perhaps even the identical tapestry seen in The Art of Painting or the Allegory of Faith. A scholar proposes that it might be associated with a Giant Leaf tapestry crafted in the Spanish Netherlands, which evoked the lush forests of the New World. Evidently, Vermeer would have encountered no obstacles in devising such an uncomplicated design anew.

The clumsy appearance of this hand and cuff

The clumsy appearance of this hand and cuff are due to overpainting by another artist.

special topics

- Girl with a Flute: is it or isn't it by Vermeer's hand?

- Flute Music and Flute Tradition

- The >Tronie: A Type of Painting Made to Sell

- Painting on Wood

- Jacob van Eyck & Dutch Flute Music

- A Pendant?

- Women's Hats

- Learning how to Play Music

- Listen to Period Flute Music

Is the Girl with a Flute an authentic work by Vermeer?

Critical assessment

The Girl with a Flute stands as the sole painting executed on panel, besides the Girl with a Red Hat. This similarity in support material, along with parallels in scale and subject matter, has led scholars to frequently consider these works as pendants. In fact, both young subjects direct their gaze expectantly towards the viewer, their eyes alert and mouths partially open. Each dons an exotic head covering, occupies a chair embellished with lion finials, and rests upon one arm. Illumination enters from the left in both compositions, casting light upon the left cheek, nose and chin of each figure. Furthermore, a delicate green glaze applied over the flesh tones indicates the shaded areas of their faces. Lastly, touches of color highlight the lower lips of their slightly parted mouths—turquoise in the Girl with a Flute and pink in the Girl with a Red Hat.

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Johannes Vermeer, 1981

The signature

No signature appears on this work.

Click here to access a complete study of Vermeer's signatures.)

Dates

c. 1665–1670

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer, London, 2000

c. 1665–1670

Walter Liedtke, Vermeer: The Complete Paintings, New York, 2008

c. 1665–1668

Wayne Franits, Vermeer, 2015

(Click here to access a complete study of the dates of Vermeer's paintings).

Technical report

The oak panel support, grained vertically, features beveled edges on the back. Exhibiting a slight convex warp, the panel also displays a minor check on the upper edge at the right, along with minor gouges, rubs and splinters on the back stemming from nails and handling. A thin, smooth white chalk ground was applied overall, followed by a coarsely textured gray ground. Underlying much of the painting, a reddish-brown underpainting serves as a foundation and is integrated into the tapestry design.

The application of paint is moderately thin, resulting in a rough texture on lighter sections. In the process, wet paint on the right cheek and chin was textured using a fingertip and subsequently glazed with a translucent green half-tone. In various areas of the white hues, particularly on the left collar and cuff, distinct wrinkles are observable, disturbing the surface. Small, irregularly shaped losses present across the surface may have originated from abrasion due to similar wrinkles occurring during previous restoration efforts.

* Johannes Vermeer (exh. cat., National Gallery of Art and Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis - Washington and The Hague, 1995, edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr.)

Provenance

- (?) Pieter Claesz van Ruijven, Delft (d. 1674); (?) his widow, Maria de Knuijt, Delft (d. 1681);

- (?) their daughter, Magdalena van Ruijven, Delft (d. 1682); (?) her widower, Jacob Abrahamsz Dissius (d. 1695);

- Dissius sale, Amsterdam, 16 May, 1696, no. 38, 39 or 40 [tronien];

- (?) Van Son family, 's-Hertogenbosch;

- Jan Mahie van Boxtel en Liempde and his wife, Geertruida van Boxtel en Liempde (née Van Son, d. 1876), 's-Hertogenbosch;

- purchased by their daughter, Jacqueline Gertrude Marie de Grez-van Boxtel en Liempde, wife of Jonkheer Jan de Grez (d.1910), Brussels (1876–1911);

- [Jonas, Paris, 1911];

- August Janssen, Amsterdam [by 1919–1921];

- [Frederick Muller, Amsterdam, and Knoedler, New York, 1921–1923, sold to Widener];

- Joseph E. Widener, Lynnewood Hall, Elkins Park, Philadelphia (1923-d.1942);

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection (acc. no. 1942.9.98).

Exhibitions

- The Hague 1907

Loan to display with permanent collection

Mauritshuis. - The Hague 1919

La Collection Goudstikker d'Amsterdam

Pulchri Studio

no. 131 and ill. - Copenhagen January, 1920

La Collection Goudstikker d#39;Amsterdam

National Gallery of Denmark (unlisted in exh. cat.) - Stockholm February, 1920

La Collection Goudstikker d'Amsterdam

Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts

(unlisted in exh. cat.) - Oslo March, 1920

La Collection Goudstikker d'Amsterdam

Oslo Konstforening

(unlisted in exh. cat.) - Rotterdam May–June, 1920

La Collection Goudstikker d#39;Amsterdam

Academie van Beeldende Kunsten.

(no. 19. and ill.) - Washington D.C 1995

Dutch Cabinet Galleries

National Gallery of Art

204–208, no. 23 as "Young Girl with a Flute" by Circle of Johannes Vermeer, and ill. - Washington D.C November 12, 1995–February 11, 1996

Johannes Vermeer

National Gallery of Art

no. 23 as "Young Girl with a Flute" by circle of Johannes Vermeer - The Hague March 1–June 2, 1996

Johannes Vermeer

Mauritshuis

204–208, no. 23 as "Young Girl with a Flute" by Circle of Johannes Vermeer and ill. - Washington D.C May 17–August 9, 1998

A Collector's Cabinet

National Gallery of Art

no. 62 - Washington D.C November 24, 1999–February 8, 2000

Johannes Vermeer's The Art of Painting

National Gallery of Art

(not in brochure) - Washington D. C. October 8, 2022–January 8, 2023

Vermeer's Secrets

National Gallery of Art - Amsterdam February 10– June 4, 2023

VERMEER

Rijksmuseum

no. 23 and ill.

(Click here to access a complete, sortable list of the exhibitions of Vermeer's paintings).

Flute music & flute tradition

Shepherd Holding a Flute

Jan van Bijlert

1630–1635

79 x 65 cm.

Private collection

In antiquity, stringed instruments held a place of great esteem. The cithara, for instance, was esteemed enough to be dedicated to Apollo, while the flute was consecrated to Dionysius due to his associations with revelry and festivities. Consequently, it was regarded as one of the most basic musical instruments, and this perception endured to a considerable extent until the 17th century.

Nonetheless, in the cultural landscape of the 17th century, the flute held a multifaceted role that extended beyond its superficial portrayal as a decorative attribute. It was a musical instrument that transcended its humble origins and became an integral part of the social fabric, reflecting the evolving tastes, aspirations and values of the time.

Its depiction in shepherd portraits and Dutch genre scenes, for example, conveyed an air of sophistication and leisure, aligning with the prevailing aesthetic of the era. In these artworks, the flute often served as a visual cue for a harmonious connection between man and nature, evoking a sense of tranquility and pastoral idyll—a sentiment that resonated with the desire for balance and solace amid the bustling urban life.

However, by the 17th century, the recorder had risen above being a mere plaything: it emerged as one of several musical instruments, occasionally refined by the craftsmanship of skilled instrument-makers. It was heard by a diverse audience, and it was played by both passionate enthusiasts and accomplished musicians such as Jacob van Eyck.

The tronie: a type of painting made to sell

Man in Oriental Dress

Frans van Mieris

1665

149.9 x 11.2 cm.

Picture Gallery of Prince Willem V, The Hague

The Girl with a Flute exemplifies the popular genre within Dutch painting known as tronie, an antiquated term referring to a specific kind of image popularized by Rembrandt and his followers. tronies were derived from living models, including artists themselves, relatives or colleagues. However, their purpose wasn't to function as formal portraits—such portraits were commissioned exclusively—instead, they were kept in the artist's studio, ready to arouse potential buyers' curiosity. Old men, attractive young women, "Turks," and valiant soldiers were all customary subjects for tronies. Artists favored attire with an especially exotic appearance, offering an avenue to experiment and display their adept technique—an attribute that represented a distinct hallmark of the professional artist. Generally fashioned on a smaller scale and dimension to match a more affordable price range, tronies were eagerly sought by collectors.

The self-portrait by Frans van Mieris, one of the Netherlands' most accomplished artists, vividly captures the characteristic flair of the Dutch tronie.

Vermeer is recognized for having created three tronies in total, among them the renowned Girl with a Pearl Earring.

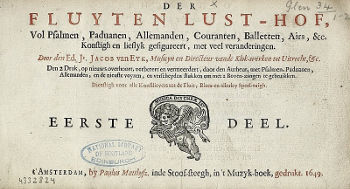

Jacob van Eyck & Dutch flute music

Jacob Van Eyck was undoubtedly one of the most notable figures in Dutch musical life during the Golden Age. A nobleman blind from birth, he gained widespread recognition as a carillonneur—an expert in bell casting and tuning. Additionally, he was highly esteemed for his exceptional virtuosity on the recorder. His collection Der Fluyten Lust-hof (The Flute's Garden of Delight) features demanding solo variations, preludes and fantasias that both captivate and challenge recorder players across the globe to this day.

It's recounted that Van Eyck used to spontaneously improvise music in the garden adjoining the Sint Janskerk in Utrecht, entertaining passersby and enchanting young couples. It's likely that someone must have attentively listened to and transcribed what amounts to nearly ten hours of music—akin to the way many contemporary jazz musicians operate. The apparent popularity of Van Eyck's music led his publisher, Paul Matthysz, to compile multiple collections during Van Eyck's lifetime. The intricacies involved in producing such a publication are intriguing to ponder, especially considering the fact that the composer himself couldn't transcribe the music. Der Fluyten Lust-hof stands as a remarkable testament to a craft that has regrettably fallen by the wayside in modern times. The art of improvisation was the very essence of music long before the advent of musical notation.

Containing approximately 150 pieces, Der Fluyten Lust-hof constitutes the largest collection of solo compositions for a single instrument ever printed. Van Eyck's compositions primarily revolve around variations on melodies that were in vogue during the Dutch Golden Age. The themes explored are diverse, encompassing Calvinist psalms, dances, contemporary hits and even ribald songs.

For centuries, this type of music found its place in the repertoire of an ancient instrument—the recorder. Played in courts, streets, churches, brothels and taverns, the recorder provided the musical backdrop. The collection offers a precious window into the musical universe of the late Renaissance and the early Baroque eras, showcasing intricate and abundant employment of diverse techniques.

A pendant?

Although Vermeer frequently revisited his artistic themes, creating pairs of works closely related in style or subject, there exists no concrete evidence to substantiate the notion that any of these works were conceived as true pendants intended to be displayed side by side. Nonetheless, the current work and the Girl with a Red Hat (images to the left) emerge as plausible candidates for a pendant pair. Both executed on panel, they share similar dimensions. Furthermore, both paintings depict young girls with slightly parted lips, adorned with peculiar hats—unlike any comparable headwear found in Dutch paintings of the Golden Age—casting a gentle shadow over their eyes. Both figures, featuring substantial pear-shaped pearl earrings, meet the viewer's gaze from an evocative half-light and are seated on Spanish-style chairs, with an unidentified tapestry hovering behind them. Additionally, the finest aspects of each work display comparable style and delicacy.

The most conspicuous argument against their pendant status is that the Girl with a Flute doesn't uphold the overall technical excellence of its counterpart. However, scientific analysis reveals that the inconsistencies can be reasonably attributed to the subpar state of conservation of the Girl with a Flute. Alternatively, the possibility that the work was intentionally left unfinished remains open.

In the context of painting, the term "pendant" refers to a pair of artworks that are intentionally created to be displayed together, often side by side, as complementary pieces. Pendants are typically linked by a common theme, subject matter, style or format and they are designed to enhance each other's meaning or visual impact when viewed together. The term originates from the French word "pendre," meaning "to hang."

The concept of pendants has been present in art for centuries, and examples can be traced back to ancient civilizations. However, the practice became more prominent and refined during the Renaissance and Baroque periods in Europe. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael and Titian created pendant works that engaged with each other's themes or subjects. The tradition continued to evolve through different artistic movements and styles.

Listen to period music

![]() "Engels Lied"("English Song") [1.82 MB]

"Engels Lied"("English Song") [1.82 MB]

from Jacob van Eyck, Der Fluyten Lust-Hof

performed by Marion Verbruggen

http://www.bach-cantatas.com/Bio/Verbruggen-Marion.htm

Soprano recorder in c, after the transitional

instrument by Richard Haka

(Amsterdam, mid-17th century),

designed by Philippe Bolton.

This instrument, also known as "Handfluyt" or

"Van Eyck"-recorder, is particularly suitable for

playing Jacob van Eyck's music and the 17th century

Italian repertoire.

The prehistoric ancestors of the recorder—used for distance communication, ritual dances and spiritual ceremonies—were crafted from bone, ivory or wood, tracing their origins back thousands of years. An early example of a recorder-like instrument, dating back about 39,000 years, was recently unearthed in a cavern in southwest Germany, marking the oldest known musical instrument. Depictions of wind instruments, possibly recorders, appear in sculptures, carvings and paintings from the 11th to the 14th century.

Throughout the 15th and 16th centuries, the recorder evolved into its "renaissance" form, coming in various sizes for ensembles. It harmonized well in "whole" consorts or contrasted with other period instruments and voices. In the early 16th century, recorders were used professionally as part of wind ensembles, accompanying instruments like shawms, cornetts, sackbuts and trumpets. In 16th-century Venice, the "pifferi" of the Doge played recorders in grand processions for the Scuola di San Marco.

Due to its accessibility (depicted in numerous Dutch paintings of the 17th century), the recorder gained popularity among amateur musicians of all social ranks, including royal households. King Henry VIII of England possessed an impressive collection of 76 recorders.

The prehistoric ancestors of the recorder—used for distance communication, ritual dances and spiritual ceremonies—were crafted from bone, ivory or wood, tracing their origins back thousands of years. An early example of a recorder-like instrument, dating back about 39,000 years, was recently unearthed in a cavern in southwest Germany, marking the oldest known musical instrument. Depictions of wind instruments, possibly recorders, appear in sculptures, carvings and paintings from the 11th to the 14th century.

Throughout the 15th and 16th centuries, the recorder evolved into its "renaissance" form, coming in various sizes for ensembles. It harmonized well in "whole" consorts or contrasted with other period instruments and voices. In the early 16th century, recorders were used professionally as part of wind ensembles, accompanying instruments like shawms, cornetts, sackbuts and trumpets. In 16th-century Venice, the "pifferi" of the Doge played recorders in grand processions for the Scuola di San Marco.

Due to its accessibility (depicted in numerous Dutch paintings of the 17th century), the recorder gained popularity among amateur musicians of all social ranks, including royal households. King Henry VIII of England possessed an impressive collection of 76 recorders.

A notable figure of the 17th century, Jacob van Eyck, blind but accomplished, stood out as a recorder virtuoso and composer of Der fluyten lust-hof (Amsterdam 1646–1649), a monumental collection of music for a solo wind instrument.

In response to evolving musical preferences in the late 16th and 17th centuries, the recorder was redesigned as a solo instrument. This new "baroque recorder," constructed in three pieces, offered enhanced accuracy and a full chromatic range of two octaves. With a reedy, powerful sound, it excelled in chamber music and solo concerti, maintaining its popularity until the early 19th century.

Integral to the recorder is its head with an internal plug or "block" (hence "Blockflöte" in German). The windway guides the player's breath to a sharp edge or "lip" (voicing edge) at the mouth's base.

The recorder features seven finger holes (sometimes with one or two doubled for semitones) and a thumb hole on the back for octaving. A recorder consort typically comprises the "descant" or "soprano," "treble" or "alto," tenor and bass instruments. Sopranino and great bass instruments are also common choices.

Womens' hats

The Artist's Bride of Three Days (detail)

Rembrandt van Rijn

Silverpoint on prepared vellum, 18.5 x 10.7 cm.

Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett

In contemporary French and Dutch language, the term "hat" could metaphorically refer to a man, while "coif" was associated with women.

Traditionally, women were discouraged from wearing the broad felt hats that were commonly worn by men in public until around the mid-1600s, when it gradually became more socially acceptable. Fashion-forward young women in Holland occasionally sported feathered hats during outings to the countryside or seaside, using them as a special form of sun protection.The particular style of hat worn by the woman depicted in this painting stands out as unusual, deliberately included for its distinctive character and visual impact.

Conversely, wide-brimmed straw hats were embraced by women across all social classes throughout Europe. These hats served the same protective purpose as their more expensive counterparts and likely held a certain allure for men. In art, they often symbolized rural life.

In the 17th-century Netherlands, women's hats were more than just a fashion statement; they were a reflection of social status, religious beliefs, and even marital standing. During this period, particularly the Dutch Golden Age, the Calvinist influence encouraged modesty in dress, but that didn't mean women's headgear lacked style or variety. However, even wealthy women tended to favor more modest, less ostentatious styles compared to their counterparts in Catholic countries like France or Italy.

Portrait of Catharina Hooghsaet (detail)

Rembrandt van Rijn

1657

Oil on canvas, 123.5 cm × 95 cm.

National Museum Cardiff, Cardiff

One of the most common types of head covering was the coif, a close-fitting cap usually made of linen. Often worn under other hats or bonnets, coifs could be simple or intricately embroidered. For colder weather, hoods made of velvet or silk were popular and could be either simple or elaborately decorated with trimmings like lace or ribbons. Broad-brimmed hats, often made of straw, were also in vogue, especially for outdoor activities. These hats could be adorned with anything from feathers to flowers, adding a touch of individuality.

Caps and bonnets were another staple, frequently worn over a coif. These could range from simple linen pieces to more elaborate creations made of luxurious materials and adorned with ribbons or lace. The millstone collar, although not a hat, was a unique feature of Dutch fashion that framed the face much like a headpiece. Made of starched linen, these collars were often intricately pleated and could be quite elaborate, adding a distinctive touch to a woman's appearance.

Regional variations also played a significant role in the types of headgear women wore. Different areas of the Netherlands had their own traditional styles, often reserved for special occasions and holidays. These could be quite distinct and elaborate, reflecting local customs and materials.

Marital status was another factor that could influence a woman's choice of head covering. While married women often opted for more modest styles, younger, unmarried women had the freedom to choose more fashionable or elaborate hats.

Learning how to play music

The Music Lesson

Gerard ter Borch

c.1665–1675

Oil on canvas, 63.6 × 50.4 cm.

Art Institue of Chicago, Chicago

The significant role of music in Dutch society found ample support within the Dutch educational system, which could arguably be regarded as one of the most exceptional in Europe during its time. Primary schools were universally accessible, catering to diverse social strata and dotting nearly every village. While the core curriculum centered on reading, writing, arithmetic and religious studies, supplementary music instruction occasionally found its place. Moving to the secondary tier, musical tutelage was extended to boys ranging from nine to seventeen years of age. Notably, the presence of Latin Schools in major towns perpetuated musical education, progressing into the realm of musical theory within the gymnasium (grammar school). However, a dedicated mentor was requisite for substantial scholarly pursuit. Those of lower socioeconomic status could earn their livelihood by aiding the master instructor.

Aside from pedagogical endeavors, budding musicians could explore several pathways. Larger Dutch municipalities employed stadspeellieden (municipal musicians), who were predominantly instrumentalists specializing in string or wind instruments. Their roles exhibited a spectrum of responsibilities, albeit frequently yielding meager remuneration.

The Music Lesson

Jan Steen

c. 1650

Oil on panel, 31.8 x 25.4 cm.

The Frick Pittsburg, Pittsburg

The nature of Vermeer's musical instruction warrants consideration. As the sole progeny of an innkeeper, Vermeer's upbringing unfolded in taverns where conviviality, commerce, tobacco, libations and music intermingled harmoniously, amid canvases obtained from his father's art trade. Moreover, it is apparent that music held some significance within the artist's familial milieu.

Vermeer's paternal step-grandfather, Nicolaes ("Claes") Corstiaensz. van der Minne, earned his livelihood as a professional musician—a speelman—besides his trade as a tailor. Documentation attests to Nicolaes's participation in public celebrations and on occasions necessitating his musical talents. His possession of diverse musical instruments, and likely instructing his progeny in musical pursuits, lends credence to the notion that he might have acquainted his son, Reynier, with a musical instrument, plausibly a flute. This lineage situates Reynier in a musical ambiance, making it plausible that he engendered a genuine affinity for music in his two offspring, Gertruy and Johannes. Though conclusive evidence remains elusive, it is reasonable to speculate that the artist's familial ties to music contribute to the pronounced recurrence of musical themes in his oeuvre.

Girl with a Flute: is it or isn't it by Vermeer's hand

In a recent inquiry, the research team at the National Gallery of Art employed cutting-edge technology to investigate the materials and painting technique employed in Girl with a Flute, which unearthed unexpected revelations that deviate from the prevailing technical data on Vermeer. The observations encompass various deviations, such as a notably coarse and brushmarked texture on the upper ground layer, an underpainting in the blue jacket that doesn't contribute to form modeling, simpler highlights in the attire and the use of coarsely ground pigments in the upper paint layers. This investigation also disclosed a greenish shadow applied with a roughness and thickness uncommon for Vermeer's approach. Further insights include prominent drying cracks stemming from shrinking that alter the surface's appearance, hinting at a somewhat unrefined finish due to an excessive count of broken bristles in the paint. Additionally, peculiarities like an unconventional green highlight near the girl's mouth, non-linear holes in the flute and inaccuracies in the conical hat's striped pattern were identified.

Based on these findings, the researchers of the National Gallery of Art assert that Vermeer likely did not directly contribute to the crafting of the painting. Instead, they propose that the tronie was produced by a contemporary artist who shared a close association with Vermeer and possessed a comprehensive grasp of his artistic techniques. This artist not only drew inspiration from Vermeer's style but also emulated his distinctive methodology. Notably, the creative process behind Girl with a Red Hat and Girl with a Flute closely parallels each other, suggesting that the creator of the latter piece might have observed Vermeer at work. Crucially, the American research team perceives the absence of technical finesse required to replicate Vermeer's masterful brushwork and nuanced effects, characterizing the artist as someone who understood the process, but was not able to achieve its effect. Furthermore, they discern signs of an unsophisticated composition and a novice application of paint, suggesting a lack of mastery in the craft.

Evidently, Girl with a Red Hat excels artistically in its details when compared to Girl with a Flute. Notable distinctions arise, such as the stylized portrayal of reflected sunlight on the lion's-head finial of the chair, showcasing a more pronounced stylization in the former piece. The softness of the girl's visage exhibits greater conviction, though it diverges from the intricate modeling in works like Girl with a Pearl Earring and Study of a Young Woman. When situated within Vermeer's broader body of work, the somewhat angular facial modeling found in The Lacemaker and Mistress and Maid also align with the technique employed here. Despite occasional descriptions of certain details as weak or awkward, the presence of challenges in rendering hands is observable in various Vermeer paintings. It's worth noting that Girl with a Flute has suffered more degradation over time compared to Girl with a Red Hat, with underlayers exposed, top layer details eroded and retouching evident in several areas, affecting the clarity of the painting.

Despite the National Gallery's findings and their interpretations, the painting was exhibited as an authentic Vermeer at the 2023 Vermeer retrospective. The majority of Vermeer scholars have refuted the Gallery's conclusion as well, with the presumption that it was likely created for study and preceded Vermeer's other three tronies.

The two exhibition curators, Pieter Roelofs and Gregor Weber, expressed their dissent as follows: "Two important questions are how an inexperienced assistant or amateur was able to achieve this innovative composition and why Vermeer, as an instructor or mentor, did not alert the painter in question to the ‘mistakes’ he or she was making. We also find several of the apparent anomalies in Girl with a Flute, such as the coarse upper layer showing visible brushstrokes and the thickly applied green earth around the face, in The Love Letter. An excessive number of broken bristles have also been found in Girl with a Pearl Earring and The Milkmaid. In addition, a number of pentimenti are visible, conceptual steps in the painting process in which the artist corrected himself, as we see here in the fur trimmings placed over the original V-neck of the jacket, the left shoulder that was lowered and the finger that was added onto the flute. This does not argue in favor of a copy or replica.

Painting on wood

Girl with a Flute, and its probable pendant tronie Girl with a Red Hat, are the only two works on wooden supports that can be linked to Vermeer. The fact that they were painted on panels has been used in the past as an argument against the authenticity of these small works, but we know from the estate inventory that at Vermeer's death in December 1675, Vermeer had, besides ten canvases, six panels ready for use. It is quite conceivable that he reserved these panels specifically for his small tronies. The surviving panel tronies have similar dimensions, comparable to the small panels used by his Leiden contemporaries Rembrandt, Gerard Dou and subsequently Frans van Mieris for this type of painting. Although dendrochronological research into the tree rings of Girl with a Red Hat has not yet proven successful, for Girl with a Flute, this method indicates that the tree from which the plank originated must have been felled between 1651 and 1661. Taking into account seasoning time, this suggests that the panel could not have been painted before approximately 1655 at the earliest, but more likely around 1665.

Painter's Studio with Color Grinder and Model Posing

David Ryckaert III

1638

Oil on panel, 59 x 95 cm.

Musee du Louvre, Paris

During the 17th century, wood panels were more readily available and cost-effective compared to canvases. Panels provided a smooth, hard surface texture compared to canvases, which allowed for different painting techniques. This surface enabled intricate details and fine brushwork, which were characteristic of the Dutch Leiden school of painting.

Wood panels used for painting were prepared through a meticulous process to ensure their stability, smoothness and longevity. Different types of wood were used, with oak and poplar being common choices. They were very thin in comparison with paintings on canvas of the samw dimension, which can be observed int some portrayals of artists working in their studios. The preparation process typically involved several steps. First, the wood panels were selected and cut to the desired size and shape. Oak was often preferred for its durability and resistance to warping, while poplar was used for its smoother surface. Sizing, a protective layer, was applied to the wood to seal the surface and prevent the paint from being absorbed into the wood fibers. This was usually done with a mixture of animal glue or gelatin, which also helped to create a barrier between the wood and subsequent layers. A mixture of powdered chalk or gypsum and animal glue, called gesso, was then applied to the sizing. Gesso provided a smooth and slightly absorbent surface that allowed the paint to adhere effectively. The ground was often applied in multiple layers, sanded between each layer to achieve a smooth finish.

The panels were then sanded to ensure the surface was even and free of imperfections. Some artists applied a thin layer of paint, called a toning layer, over the gesso to establish a neutral base color. This toning helped to create a harmonious starting point for subsequent layers of paint.